Introduction

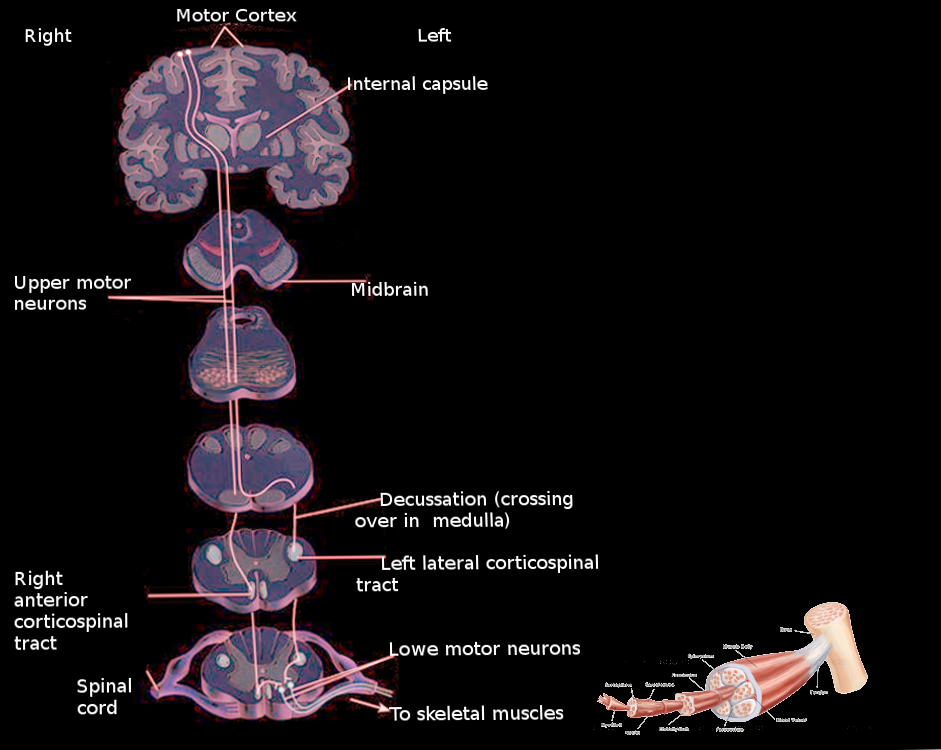

The control of muscular movements in the human brain is a very complex, yet delicate process. Multiple areas of the brain are involved, each of which is responsible for specific areas and functions. This control is conveyed mainly through the pyramidal tract, which arises from the pyramidal cell in the cortex, primarily the primary motor cortex. It divides into the corticospinal tract, which synapses with the lower motor neurons innervating the muscles in the limbs and trunk, and the corticobulbar tract, which synapses with the cranial nerves to control muscular movements of the face, head, and neck.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The pyramidal tract originates from the cerebral cortex, and it divides into two main tracts: the corticospinal tract and the corticobulbar tract. Each of these tracts carry efferent signals to either the spinal cord or the brainstem.

The spinal cord receives fibers from the corticospinal tract, which control the movements in the limbs and trunk. The corticospinal tract originates mainly from the primary motor cortex and premotor area, while also receiving fibers from the somatosensory cortex, cingulate gyrus, and the parietal lobe. Along its descent, it passes through the corona radiata and internal capsule, cerebral peduncles, pons, and upper medulla. Decussation of the fibers (i.e., the crossing of fibers to the opposite side of the body) occurs at the level of the lower medulla, where 85 to 90% of the fibers cross to form the lateral corticospinal tract (LCST). Within the spinal cord, the lateral corticospinal tract descends in the lateral funiculus and terminates at each level of the spinal cord by synapsing with lower motor neurons controlling gross and fine motor movements. Non-decussating fibers continue on the same side within the spinal cord as the anterior corticospinal tract (ACST) and control the proximal muscles as well as the trunk.

The corticobulbar tract is involved in the movement of the face, head, and neck. Its fibers originate in the primary motor cortex, descend similarly to the corticospinal tract through the corona radiata and the internal capsule, and exit to synapse with the lower motor neurons of the cranial nerves. These fibers innervate all cranial nerves bilaterally except cranial nerves VII and XII, which receive their innervation from the contralateral cortex.[1][2][3]

Embryology

The cerebral cortex gives rise to the corticospinal tract, specifically, the pyramidal cells from layer V in the rostral and frontal parts of the cerebral cortex. Corticospinal projections arise from both the motor and the somatosensory cortices. Despite its importance, the corticospinal tract develops slowly and rather late. The tract reaches the level of pyramidal decussation at about eight weeks after fertilization and subsequent development is slow. Myelination of its axons can take up to two to three years. Due to this lengthy development, malformations can occur after birth. The genetic factors involved in tract development are complicated, and much of this process is yet to be known.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Each part of the pyramidal tract receives vascular supply by a different artery depending on its anatomical position. The primary motor cortex, from which the pyramidal tract originates, is supplied by the middle cerebral artery (MCA), The MCA is responsible for supplying the face and upper extremities, while the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) supplies the lower extremities. Following the course of the pyramidal tract, it passes through the corona radiata and internal capsule, supplied by the lenticulostriate arteries, which are branches of the MCA. The tract continues to pass inferiorly into the brainstem, where the basilar artery provides arterial support. Blockages to the mentioned arteries will manifest as weakness in the body parts controlled by the areas supplied.[1][5][6]

Physiologic Variants

Pyramidal tract autopsy studies showed variabilities on many levels of its course, including the pyramidal decussation. In some cases, pyramidal decussation was absent, while in other cases, only partial decussation was present. Moreover, fibers from each hemisphere could cross at different levels, as fibers from the left pyramid could decussate at a more cranial level and in higher numbers compared to its counterpart on the right side.[4]

Surgical Considerations

Pyramidal tract lesions are identifiable from the set of symptoms presented in the patient and should be managed quickly to avoid devastating consequences. Symptoms vary depending on the lesion site and tract involved. Spasticity, clonus, and hyperreflexia are common themes in corticospinal injuries which cause impairment to the movement of the limbs and trunk. Corticobulbar damage causes impaired facial and hypoglossal nerves functions. A detailed history and physical examination provide enough information to predict the site of injury. By utilizing imaging and other modalities, the insult, if applicable, can be accessed surgically and treated.

Management of these lesions involve intensive rehabilitation and exercise, medical interventions such as botulinum toxin, and benzodiazepines to decrease spasticity and contractures. Surgery is reserved for severe and life-threatening complications or in those whose medical therapy has failed to provide relief and improve the quality of life.[7]

Clinical Significance

The pyramidal tract, especially the corticospinal tract, plays a significant role in controlling voluntary muscular movements. As a result, severe lesions can cause many devastating consequences. Different insults can cause lesions in the pyramidal tract, which include strokes, tumors, hemorrhage, meningitis, trauma, and even multiple sclerosis.

Understanding the decussation of the corticospinal tract will help localize anatomical sites based on the clinical signs and symptoms and vice versa. Any damage to the tract above the level of decussation will lead to impairment on the contralateral side of the body. Lesions in the spinal cord below the level of decussation will manifest in the ipsilateral side Pyramidal tract lesions will lead to spasticity, hyperreflexia, clonus, and positive Babinski sign, as the pyramidal tract is a part of the upper motor neuron system

Meanwhile, lesions in the corticobulbar tract can manifest as pseudobulbar palsy, which presents as slow speech, dysphagia, dysarthria, spastic tongue. Additional corticobulbar tract lesions can lead to impaired function of cranial nerves VII and XII, which present as contralateral lower facial droop and weakness in the hypoglossal muscles.

Diseases that involve damage to the pyramidal tract include strokes, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), central pontine myelinolysis, Friedreich ataxia, and Brown-Sequard syndrome.[2][8][1][9][10]

Media

References

Lohia A, McKenzie J. Neuroanatomy, Pyramidal Tract Lesions. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082020]

Van Wittenberghe IC, Peterson DC. Corticospinal Tract Lesion. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194358]

Emos MC, Agarwal S. Neuroanatomy, Upper Motor Neuron Lesion. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725990]

ten Donkelaar HJ, Lammens M, Wesseling P, Hori A, Keyser A, Rotteveel J. Development and malformations of the human pyramidal tract. Journal of neurology. 2004 Dec:251(12):1429-42 [PubMed PMID: 15645341]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNavarro-Orozco D, Sánchez-Manso JC. Neuroanatomy, Middle Cerebral Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252258]

Matos Casano HA, Tadi P, Ciofoaia GA. Anterior Cerebral Artery Stroke. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30726018]

Rhee PC. Surgical Management of Upper Extremity Deformities in Patients With Upper Motor Neuron Syndrome. The Journal of hand surgery. 2019 Mar:44(3):223-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.07.019. Epub 2018 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 30266480]

Emos MC, Rosner J. Neuroanatomy, Upper Motor Nerve Signs. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082126]

Natali AL, Reddy V, Bordoni B. Neuroanatomy, Corticospinal Cord Tract. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571044]

Shams S, Arain A. Brown-Sequard Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844162]