Introduction

Teeth serve multiple functions beyond mastication, including shaping the kinetics of phonation, breathing, maintaining a patent airway, and serving as a foundation for the vertical dimensions of the face.[1] The maxilla and mandible, which together form the jaw, contain alveolar bone, a thick ridge of bone that forms the sockets of the teeth. Appropriate size and jaw positioning are critical in developing a proper bite (occlusion) and subsequent mastication. As will be discussed later in detail, certain teeth have specialized roles in chewing, with the entire group functioning as a dynamic entity.[2]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Poor dental and oral health can potentially lead to numerous issues. Of particular concern is plaque, a biofilm of various bacteria (mainly Streptococcus and anaerobes) that form on the surface of teeth. Brushing alone does not always remove plaque in its entirety. If plaque is not professionally removed regularly, periodontal problems and gingivitis can set in. Plaque can mineralize, eventually leading to tartar build-up, causing gingivitis, halitosis, and dental caries.

Streptococcus mutans is the most important bacteria associated with dental caries.[3] Bacteria live off the remains of food, especially that of sugar and starches. In the absence of oxygen, these bacteria produce lactic acid, dissolving calcium and phosphorous in the enamel. Demineralization of enamel then leads to tooth destruction. Remineralization of enamel occurs through saliva, which keeps the tooth surface above a critical pH of 5.5. Of concern, however, is that saliva is unable to penetrate through plaque, and demineralization can occur.[4]

Nutrition is also of specific concern in the development and growth of teeth. The availability of calcium and phosphate in the diet and the amount of vitamin D in the body are all factors that can lead to changes in the enamel and growth of healthy, normal teeth. Defect calcification occurs when these factors are deficient, leading to abnormal teeth development throughout life.[5]

Cellular Level

The tooth bud, an aggregation of cells that eventually forms a tooth, is organized into three parts: enamel organ, dental papilla, and dental follicle.[6]

The enamel organ comprises four layers; the inner and outer enamel epithelium, the stratum intermedium, and the stellate reticulum. The enamel is made before a tooth erupts into the mouth by the enamel organ, which contains cells called ameloblasts. These cells die once the tooth erupts, which means that the ability to make enamel is forever lost once eruption occurs.[7]

The dental papilla is a fusion of ectomesenchymal cells, termed odontoblasts, which form dentin, the yellow substance that forms the bulk of the teeth. Dentin consists of calcium, phosphorous, and hydroxyapatite crystals bound together in a hard crystalline substance.[8]

The dental follicle gives rise to three major cell types: cementoblasts, osteoblasts, and fibroblasts. Cementoblasts form the cementum (calcified material covering teeth roots), osteoblasts give rise to the alveolar bone around the roots of the teeth, and fibroblasts develop the periodontal ligaments which connect teeth to the alveolar bone through the cementum.[9]

Development

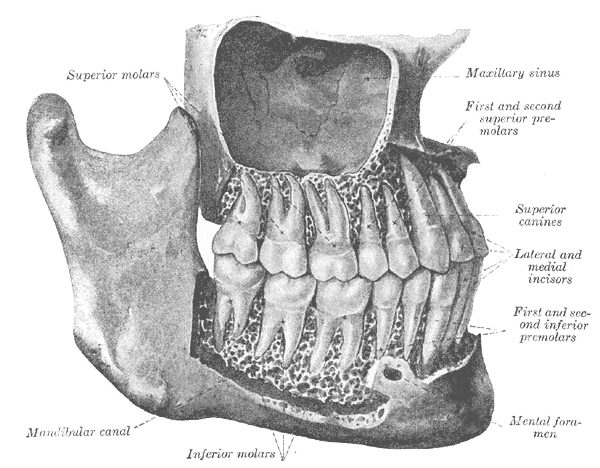

Two main sets of dentition exist; a primary dentition (colloquially referred to as baby teeth) and an adult or permanent dentition. Under normal physiological conditions, a human will have 20 deciduous (baby) teeth and 32 permanent teeth (see Image. Permanent Teeth, Viewed From the Right).

The process of tooth development begins with the tissues of the first pharyngeal arch. It is a complex process resulting from interactions between the oral cavity ectoderm, which gives rise to cells that produce enamel. The neural crest ectomesenchyme gives rise to tooth structures other than enamel. Primary dentition begins to form in-utero between 6 and 8 weeks of gestation. Permanent teeth begin to form in utero at 20 weeks of gestation. If the structures do not start to develop at or near these times, they will not develop at all.[10]

Eruption of primary teeth into the mouth begins between the ages of 6 months and two years. Typically, the bottom two front teeth, the bottom central incisors, are the first to erupt. All deciduous teeth should have erupted by the time the child is three years of age. At approximately six years of age, the first permanent tooth erupts, typically the central incisor. Except for the third molars, the wisdom teeth, the process finishes around the age of 13 years with the eruption of the second molar. The third molars typically erupt around ages 17 to 25 years. However, in some cases, they may never erupt due to either the absence of development or remaining impacted in the jaw.[11]

The nerves that provide the sensations of pain, touch, and temperature changes to the teeth are branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V). The second main branch of CN V is the maxillary nerve, which innervates the upper row of teeth with smaller branches, the superior alveolar nerves. The third branch of CN V is the mandibular nerve, which innervates the bottom row of teeth.[12]

Both rows of teeth are supplied by small branches of the maxillary artery, a branch of the external carotid artery. The maxillary arch is supplied by a plexus of three arterial branches, which include the anterior superior alveolar artery (ASAA), the middle superior alveolar artery (MSAA), and the posterior superior alveolar artery (PSAA). The ASAA arises from the infraorbital artery, a branch of the maxillary artery, to supply the anterior maxillary teeth and gingiva.[13] The inferior alveolar artery, another branch of the maxillary artery, supplies the mandible.[14]

Function

Due to its high mineral content, enamel, which covers the visible part of the tooth (the crown), is the hardest substance in the human body, and for a good reason.[7] Teeth must maintain the ability to be fracture-resistant and exert extreme amounts of force and pressure to perform their functions. The primary function of teeth is mastication, which involves the cutting, mixing, and grinding of food to allow the tongue and oropharynx to shape it into a bolus that can be swallowed.[15]

The teeth are generally conceptualized as a U-shape, with the bottom of the U representing the front teeth. The upper arch is the maxillary arch, with the teeth embedded in the maxilla, and the lower arch is the mandibular arch, with the teeth embedded in the mandible. The shape of the crown, in combination with arch mechanics and its position in the mouth, determines a tooth’s function in chewing.

The anterior teeth are called incisors, directly reflecting their role in cutting food into smaller pieces without performing any grinding function. There are eight incisors in normal adult dentition; two central and two lateral incisors on each arch.[16] The incisors have a maximal biting force value of approximately 43.3 kg (95.5 lbs).[17]

Moving posteriorly, the next tooth is the canine, or the cuspid, known as the cornerstone of the dental arch. The canine is considered one of the most important teeth due to its crucial role in jaw dynamics, helping to control how the teeth slide on and off each other. The canine often has the longest root and is fastened tightly to the bone. Canine teeth function to tear and puncture holes.[18]

Posterior to the canines are the eight premolars (bicuspids), four in each arch, which assist in crushing, grinding, and mixing food.[19] The bicuspids have a maximal biting force value of approximately 99.11 kg (218.5 lbs).[17]

The most posterior functioning teeth are the first and second molars. Adults have eight molars, four per arch, with many adults having more posterior third molars (wisdom teeth). Third molars are often extracted for reasons beyond the scope of this article; it should be understood that wisdom teeth rarely contribute to mastication.[20] The first molars have a maximal biting force value of approximately 120.66 kg (266 lbs).[17]

Mechanism

To better understand how teeth function, one must understand the mechanics of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The TMJ is located where the mandible articulates with the skull, directly in front of the auditory canal. Numerous muscles and ligaments guide and control the TMJ, but at the most basic level, the mandible has two possible movements; rotation and translation. When the mouth initially opens, the mandible will rotate and then slide forward at a certain point to allow further opening, which is called translating. This translational movement occurs by two joint spaces within the joint and a cartilaginous disc between them, making it a ginglymoarthrodial joint; it both hinges and slides.[21]

These mechanics translate to the relationship of the arches to one another. The lower jaw can protrude and move side-to-side (i.e., laterally). Together, the range of these movements is called the envelope of occlusion.[22] This envelope allows for idealized tooth mechanics, which minimize shear forces and maximize vertical ones. Teeth sit in the jaw bone but do not directly touch the bone. They are embedded in what amounts to a shock absorber called the periodontal ligament. This system is designed to withstand and exert forces in a vertical vector (chewing), which they can do effectively with hundreds of pounds or kilograms of vertical force.[23] The teeth are weakest in shear (lateral) forces. Therefore, all the anatomic and mechanical concepts outlined above work in concert to allow the teeth to grind, mix, and cut food vertically while avoiding shear forces on them.

Occlusion is the term for how teeth fit together and interlock. In proper occlusion, the maxillary arch and teeth sit slightly anterior to the mandibular arch and teeth. In a transverse dimension, the maxillary teeth sit more lateral than the mandibular teeth. Correct occlusion is essential for the primary function of teeth, as a tight meshwork allows for efficient mastication. When this fitment is not ideal, it is called malocclusion, discussed in a later section.

The concept of the envelope of occlusion helps us understand how the teeth should function physiologically. When a patient bites together so that the teeth touch in a normal position (an excellent cue to help patients do this is to ask them to bite on their back teeth) and then slides the lower jaw forward slowly, one will note that the front teeth slide against each other, but the back teeth open and no longer touch. This is called anterior guidance and is an important secondary function of the anterior teeth (the incisors and canines). This function minimizes shear forces on the posterior teeth.

From the same starting position with normal occlusion, if one, again keeping the teeth together, slides the lower jaw to one side, one will note that the teeth on the ipsilateral side touch, but the teeth on the contralateral side do not. In some people, only the canines touch here. Again, this is a function to help prevent shear forces in excursive or sideways movements.[24]

Beyond mastication, teeth have an essential role in phonation. For example, when a fricative sound is made, like saying the letter F, one will note that the maxillary incisors rest against or close to the vermillion border of the lower lip.

Finally, teeth, like bones, also participate in mineral exchange. The tooth's inner layers, closest to the circulatory supply and pulp, are most active in this regard, although the enamel may exchange minerals with saliva.[25]

Pathophysiology

The two most common dental abnormalities are dental caries and malocclusion.

Dental Caries

Dental caries, better known as tooth decay or cavities, is a multifactorial disease that leads to demineralization of the teeth and subsequent areas of decay, or 'holes.' Symptoms of tooth decay include pain, infection, and tooth loss. In the United States, dental caries is the most common chronic childhood disease, five times more common than asthma.

Dental caries results from the activity of bacteria on teeth, most commonly Streptococcus mutans. The inciting event in the development of dental caries is the deposition of plaque on the tooth, a film of precipitated products of saliva and food. The bacteria which inhabit plaque depend greatly on carbohydrates for activation and multiplication. These bacteria also form acids (lactic acid) and proteolytic enzymes, which cause caries due to the now highly acidic environment dissolving the calcium salts of teeth.[26]

Malocclusion

Malocclusion is the term used to describe misaligned teeth. Malocclusion is typically a hereditary abnormality that causes the teeth not to interdigitate appropriately and, therefore, cannot perform the regular cutting and grinding actions. Misaligned teeth can occasionally result in abnormal displacement of the lower jaw in relation to the upper jaw and cause mandibular joint pain and tooth deterioration.[27]

An orthodontist is a dental school graduate with an advanced orthodontic degree specializing in dental development, occlusion, facial growth, and jaw alignment. An orthodontist can correct malocclusions using braces, which apply gentle, prolonged pressure against the teeth. This pressure causes absorption of alveolar jaw bone on the compressed side of the tooth and new bone deposition on the tension side of the tooth, which gradually moves the tooth to a new, desired position.[28]

Additional dental anomalies can occur due to developmental or environmental causes.

Developmental Dental Anomalies

- Abnormalities of Tooth Number

- Anodontia is characterized by a total lack of tooth development.[29]

- Hyperdontia is characterized by an increased number of teeth. Systemic causes of hyperdontia may include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Gardner syndrome, Sturge-Weber syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, cleidocranial dysostosis, and Apert syndrome.[30]

- Hypodontia is characterized by the developmental absence of one or more teeth. Systemic causes of hypodontia may include ectodermal dysplasia, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Gorlin syndrome.

- Oligodontia is characterized by the absence of six or more teeth.

- Abnormalities of Tooth Size

- Microdontia is characterized by teeth that are smaller than average size. True generalized microdontia, a rare condition where all teeth are affected, often accompanies other systemic syndromes, such as congenital growth hormone deficiency, oro-faciodigital syndrome, or oculo-mandibulo-facial syndrome. Microdontia can also be seen in young patients who have previously undergone chemoradiotherapy, which alters the formation of the developing dentition.[31]

- Macrodontia is characterized by teeth that are larger than average size. Macrodontia of all teeth occurs in pituitary gigantism and pineal hyperplasia.

- Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate

- Dental abnormalities are commonly seen on the side affected by the cleft and may include supernumerary, discolored, or missing teeth.[32]

Environmental Dental Anomalies

- Anomalies Occurring During Tooth Development

- Enamel hypoplasia is characterized by inadequate amounts of enamel formed due to nutritional factors, untreated celiac disease, hypocalcemia, preterm birth, birth injury or trauma, or exanthematous diseases (i.e., congenital syphilis, chickenpox).

- Anomalies Occurring After Tooth Development

- Dental caries[33]

- Dental infection/abscess may be due to poor oral and dental health, leading to Ludwig angina (LA), a potentially life-threatening bacterial infection occurring in the floor of the mouth. LA often develops secondary to a dental infection/abscess, with over 90% of cases originating from a 2nd or 3rd mandibular molar dental infection.[34]

- Tooth destruction in the setting of acidic erosion (i.e., bulimia, GERD).

- Discoloration of teeth can take many forms. Red-brown discoloration may be due to congenital erythropoietic porphyria causing porphyrins to be deposited on teeth. Blue discoloration may be due to alkaptonuria. Green discoloration is often due to biliverdin deposition and may be seen in erythroblastosis fetalis and biliary atresia.

Clinical Significance

Oral health directly affects the overall health and quality of life of an individual. Studies have shown that patients with poor oral health have increased mortality and are more likely to develop respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus.[35]

As a healthcare provider, it is important to discuss with patients the concept of proper oral hygiene and its importance in preventing dental caries, periodontal disease, halitosis, and gingivitis. Despite careful brushing and flossing, plaque buildup and tartar can form and must periodically be cleaned professionally. It is important to advise patients to brush twice a day to prevent the formation of plaque and tartar. Flossing should be done once per day, as it removes plaque from between the teeth and prevents periodontal disease.[36] Oral health should be incorporated into routine primary care health through counseling about diet, oral hygiene, smoking cessation, and screening for dental disease.

The eruption and composition of teeth are influenced by body metabolism, endocrine function, genetics, and local factors.[37] Alterations in hormone levels, vitamin and mineral levels, and ingestion of drugs can permanently alter the teeth.[38]

Certain drugs and prescription medications can affect dentition, including changing the color, eroding the enamel, and causing dental caries. For example, medications that can lead to gingival hyperplasia include calcium channel blockers and phenytoin. Medications that can lead to oral inflammation (stomatitis) include inhaled corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, and chemotherapy. Sugar-containing medications, including antacids and cough syrups, can lead to enamel erosion. Medications that can lead to dry mouth (xerostomia) include SSRIs, antipsychotics, diuretics, antihistamines, opioids, decongestants, and antihypertensives such as atenolol and clonidine.[39]

In addition, research shows that if teeth are exposed to tetracycline at the time of tooth calcification and mineralization, tetracycline will bind calcium ions in the teeth. If this occurs before tooth eruption, the bound tetracycline will cause the teeth to erupt with an initial fluorescent yellow discoloration. Once the teeth have been exposed to light over a few months to years, tetracycline will oxidize, and the discoloration will change to a nonfluorescent brown or gray.[40]

As previously mentioned, teeth play a functional role in speech, with the loss of these teeth affecting the formation of the fricative sound and, by extension, many other sounds. Another important concept is the vertical dimension of occlusion. A lack of teeth, or extreme wear and destruction of teeth, can cause the jaw to over-close, resulting in accentuated nasolabial folds and an aged appearance, which speaks to the cosmetic function of teeth. As the soft tissues of the face lose support, phonation, bolus creation, and swallowing can also be affected.[41]

Of clinical importance to all medical specialties is the proper numbering of teeth. The numbering of teeth begins from right to left, 1-32, with the upper right third molar (wisdom tooth) being tooth number one. Moving from right to left, top to bottom, 1-16 involves the upper teeth. Tooth number 17 is the lower left third molar, then traveling from left to right, ending at tooth number 32, the bottom right third molar.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Permanent Teeth, Viewed From the Right. The external layer of bone has been partly removed, and the maxillary sinus has been opened.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Traser L, Birkholz P, Flügge TV, Kamberger R, Burdumy M, Richter B, Korvink JG, Echternach M. Relevance of the Implementation of Teeth in Three-Dimensional Vocal Tract Models. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR. 2017 Sep 18:60(9):2379-2393. doi: 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-S-16-0395. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28898358]

Shrestha D, Rajbhandari P. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Tooth Wear. JNMA; journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 2018 Jul-Aug:56(212):719-723 [PubMed PMID: 30387456]

Peterson SN, Snesrud E, Liu J, Ong AC, Kilian M, Schork NJ, Bretz W. The dental plaque microbiome in health and disease. PloS one. 2013:8(3):e58487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058487. Epub 2013 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 23520516]

Farooq I, Bugshan A. The role of salivary contents and modern technologies in the remineralization of dental enamel: a narrative review. F1000Research. 2020:9():171. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22499.3. Epub 2020 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 32201577]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoynihan P, Petersen PE. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of dental diseases. Public health nutrition. 2004 Feb:7(1A):201-26 [PubMed PMID: 14972061]

Honda MJ, Fong H, Iwatsuki S, Sumita Y, Sarikaya M. Tooth-forming potential in embryonic and postnatal tooth bud cells. Medical molecular morphology. 2008 Dec:41(4):183-92. doi: 10.1007/s00795-008-0416-9. Epub 2008 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 19107607]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHu JC, Chun YH, Al Hazzazzi T, Simmer JP. Enamel formation and amelogenesis imperfecta. Cells, tissues, organs. 2007:186(1):78-85 [PubMed PMID: 17627121]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoldberg M, Kulkarni AB, Young M, Boskey A. Dentin: structure, composition and mineralization. Frontiers in bioscience (Elite edition). 2011 Jan 1:3(2):711-35 [PubMed PMID: 21196346]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSowmya S, Chennazhi KP, Arzate H, Jayachandran P, Nair SV, Jayakumar R. Periodontal Specific Differentiation of Dental Follicle Stem Cells into Osteoblast, Fibroblast, and Cementoblast. Tissue engineering. Part C, Methods. 2015 Oct:21(10):1044-58. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2014.0603. Epub 2015 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 25962715]

Rathee M, Jain P. Embryology, Teeth. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809350]

Renton T, Wilson NH. Problems with erupting wisdom teeth: signs, symptoms, and management. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2016 Aug:66(649):e606-8. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X686509. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27481985]

Rodella LF, Buffoli B, Labanca M, Rezzani R. A review of the mandibular and maxillary nerve supplies and their clinical relevance. Archives of oral biology. 2012 Apr:57(4):323-34. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.09.007. Epub 2011 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 21996489]

Nishimura T, Okuda H. Arterial supply of the maxillary teeth in the crab-eating monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 1993 Mar:69(6):265-75 [PubMed PMID: 8469518]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNguyen JD, Duong H. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Inferior Alveolar Arteries. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613516]

Peyron MA , Santé-Lhoutellier V , François O , Hennequin M . Oral declines and mastication deficiencies cause alteration of food bolus properties. Food & function. 2018 Feb 21:9(2):1112-1122. doi: 10.1039/c7fo01628j. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29359227]

Wolfart S, Quaas AC, Freitag S, Kropp P, Gerber WD, Kern M. Subjective and objective perception of upper incisors. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2006 Jul:33(7):489-95 [PubMed PMID: 16774506]

Zhao Y, Ye D. [Measurement of biting force of normal teeth at different ages]. Hua xi yi ke da xue xue bao = Journal of West China University of Medical Sciences = Huaxi yike daxue xuebao. 1994 Dec:25(4):414-7 [PubMed PMID: 7744385]

Sapkota B, Gupta A. Pattern of occlusal contacts in lateral excursions (canine protection or group function). Kathmandu University medical journal (KUMJ). 2014 Jan-Mar:12(45):43-7 [PubMed PMID: 25219993]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUngar PS. Tooth form and function: insights into adaptation through the analysis of dental microwear. Frontiers of oral biology. 2009:13():38-43. doi: 10.1159/000242388. Epub 2009 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 19828967]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAdeyemo WL. Do pathologies associated with impacted lower third molars justify prophylactic removal? A critical review of the literature. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2006 Oct:102(4):448-52 [PubMed PMID: 16997110]

Nickel JC, Iwasaki LR, Gonzalez YM, Gallo LM, Yao H. Mechanobehavior and Ontogenesis of the Temporomandibular Joint. Journal of dental research. 2018 Oct:97(11):1185-1192. doi: 10.1177/0022034518786469. Epub 2018 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 30004817]

Fling M. Understanding the envelope of parafuntion. Texas dental journal. 2009 Dec:126(12):1198-9 [PubMed PMID: 20131615]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHuang H, Yang R, Zhou YH. Mechanobiology of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells in Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Stem cells international. 2018:2018():6531216. doi: 10.1155/2018/6531216. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30305820]

Kohaut JC. Anterior guidance--movement and stability. International orthodontics. 2014 Sep:12(3):281-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ortho.2014.06.010. Epub 2014 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 25130522]

Heller D, Helmerhorst EJ, Oppenheim FG. Saliva and Serum Protein Exchange at the Tooth Enamel Surface. Journal of dental research. 2017 Apr:96(4):437-443. doi: 10.1177/0022034516680771. Epub 2016 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 27879420]

Bowen WH. Dental caries - not just holes in teeth! A perspective. Molecular oral microbiology. 2016 Jun:31(3):228-33. doi: 10.1111/omi.12132. Epub 2015 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 26343264]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMwangi CW, Richmond S, Hunter ML. Relationship between malocclusion, orthodontic treatment, and tooth wear. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2009 Oct:136(4):529-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.11.030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19815154]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAbreu LG. Orthodontics in Children and Impact of Malocclusion on Adolescents' Quality of Life. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2018 Oct:65(5):995-1006. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2018.05.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30213359]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcKinney R, Olmo H. Developmental Disturbances of the Teeth, Anomalies of Number. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34424644]

Bayar GR, Ortakoglu K, Sencimen M. Multiple impacted teeth: report of 3 cases. European journal of dentistry. 2008 Jan:2(1):73-8 [PubMed PMID: 19212513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcKinney R, Olmo H. Developmental Disturbances of the Teeth, Anomalies of Shape and Size. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34662069]

Tereza GP, Carrara CF, Costa B. Tooth abnormalities of number and position in the permanent dentition of patients with complete bilateral cleft lip and palate. The Cleft palate-craniofacial journal : official publication of the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. 2010 May:47(3):247-52. doi: 10.1597/08-268.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20426674]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBardellini E, Amadori F, Pasini S, Majorana A. Dental Anomalies in Permanent Teeth after Trauma in Primary Dentition. The Journal of clinical pediatric dentistry. 2017:41(1):5-9. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-41.1.5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28052204]

An J, Madeo J, Singhal M. Ludwig Angina. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493976]

Kotronia E, Brown H, Papacosta AO, Lennon LT, Weyant RJ, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Ramsay SE. Oral health and all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory mortality in older people in the UK and USA. Scientific reports. 2021 Aug 12:11(1):16452. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95865-z. Epub 2021 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 34385519]

Attin T, Hornecker E. Tooth brushing and oral health: how frequently and when should tooth brushing be performed? Oral health & preventive dentistry. 2005:3(3):135-40 [PubMed PMID: 16355646]

Lopes CMI, Cavalcanti MC, Alves E Luna AC, Marques KMG, Rodrigues MJ, DE Menezes VA. Enamel defects and tooth eruption disturbances in children with sickle cell anemia. Brazilian oral research. 2018 Aug 13:32():e87. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2018.vol32.0087. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30110085]

Retrouvey JM, Taqi D, Tamimi F, Dagdeviren D, Glorieux FH, Lee B, Hazboun R, Krakow D, Sutton VR, Members of the BBD Consortium. Oro-dental and cranio-facial characteristics of osteogenesis imperfecta type V. European journal of medical genetics. 2019 Dec:62(12):103606. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.12.011. Epub 2018 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 30593885]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStephens MB, Wiedemer JP, Kushner GM. Dental Problems in Primary Care. American family physician. 2018 Dec 1:98(11):654-660 [PubMed PMID: 30485039]

Cohlan SQ. Tetracycline staining of teeth. Teratology. 1977 Feb:15(1):127-9 [PubMed PMID: 841479]

Boyce JO, Kilpatrick N, Teixeira RP, Morgan AT. Say 'ahh'… assessing structural and functional palatal issues in children. Archives of disease in childhood. Education and practice edition. 2020 Jun:105(3):172-173. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-316320. Epub 2018 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 30567832]