Introduction

Aortic stenosis is a common valvular disorder leading to left ventricular outflow obstruction.[1] The anterograde velocity across the valve must be at least 2 m/sec, whereas aortic valve sclerosis is the thickening and calcification without a significant pressure gradient. Etiologies include congenital (bicuspid/unicuspid), calcific, and rheumatic disease. Symptoms such as exertional dyspnea or fatigue gradually develop after a long asymptomatic latent period of about 10 to 20 years. Patients go on to develop chest pain, heart failure, and syncope. The definitive treatment for aortic stenosis includes aortic valve replacement, either via a surgical or percutaneous approach. Survival is excellent during the asymptomatic phase, but mortality is more than 90% within a few years after the onset of symptoms.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Congenital

A congenitally abnormal valve with superimposed calcification can cause aortic stenosis.[8] The bicuspid aortic valve is the most common cause of aortic stenosis in patients less than the age of 70 years in developed countries.

Acquired

Rheumatic valve disease is the most common cause in developing countries.[8] The commissures of the leaflets fuse to leave a small central orifice. Other causes include calcification of the tri-leaflet valve, alkaptonuria, systemic lupus erythematosus, ochronosis, irradiation, homozygous type II lipoproteinemia, and metabolic diseases such as Fabry disease.[9][10] Mineral metabolism disturbances, such as end-stage renal disease, have also been shown to contribute to the calcification of the valve.[11] Obstruction to the left ventricular (LV) outflow can occur above or below the valve, causing supravalvular stenosis and subvalvular stenosis, respectively. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can cause dynamic subvalvular stenosis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of calcific aortic sclerosis is about 1% to 2% in patients aged 65 or less and 29% in patients aged 65 or more. About 2 to 9% of patients aged greater than 75 have severe aortic stenosis.[12][13] The prevalence of aortic sclerosis ranges from 9 to 45% in patients with a mean age of 54 to 81 and increases with age.[14] The relative prevalence of aortic stenosis in patients with tri-leaflet versus congenitally abnormal valves varies with age.[15] The causes of aortic stenosis vary geographically as calcific stenosis is more common in North America and Europe, while rheumatic valve disease is more common in developing countries. The number is expected to increase twofold or threefold in the coming decades with the aging of the population.[16]

Pathophysiology

Left ventricular (LV) obstruction caused by the stenosis of the valve increases LV systolic pressure. It also results in increased LV ejection time (LVET), decreased aortic pressure, and increased LV end-diastolic pressure. The increased afterload, in addition, to an increase in LV volume overload, leads to an increase in LV mass, ultimately leading to LV dysfunction and failure. Myocardial oxygen consumption increases with increased LV systolic pressure, LV mass, and LVET, while myocardial perfusion time decreases with increased LVET. Hence, LV function further deteriorates with increased myocardial oxygen consumption and decreased myocardial oxygen supply.[8]

History and Physical

The acquired aortic stenosis manifests with exertional dyspnea, syncope, angina, and, ultimately, heart failure.[17][18] Typically, symptoms begin at the age of 50 to 70 years in patients with the bicuspid aortic valve and in greater than 70 years in patients with tri-leaflet valve calcific stenosis. Patients progressively experience a gradual decrease in exercise tolerance, dyspnea on exertion, and fatigue. Severe exertional dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, and pulmonary edema show various degrees of pulmonary venous hypertension. Angina results from the combination of the need for increased oxygen in hypertrophied myocardium and reduction of oxygen delivery secondary to the excessive compression of coronary vessels. Syncope is caused by the decrease in cerebral perfusion occurring during exertion when the arterial pressure declines due to systemic vasodilation and an inadequate increase in cardiac output related to stenosis. It is also due to the malfunction of the baroreceptor mechanism in severe aortic stenosis. Non-cardiac symptoms include gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and cerebral emboli. GI bleeding is observed in patients with severe aortic stenosis and is often associated with angiodysplasia or other vascular malformations. It manifests from shear stress-induced platelet aggregation and reduction in the von Willebrand factor.[19] Cerebral emboli occur due to microthrombi formation on thickened bicuspid valves. There is also an observed increase in the risk of infective endocarditis in patients with aortic valve disease, especially with a bicuspid valve. On examination, carotid upstroke can be observed on palpation. A slow-rising, late-peaking, and a low-amplitude carotid impulse, pulsus parvus et tardus, is an expected finding in severe aortic stenosis and, when present, is specific to aortic stenosis. On auscultation, the second heart sound may lack a split and can be heard as a single sound during inspiration. It can also become paradoxical when the closure of the aortic valve gets delayed than the pulmonic valve. A mid-systolic ejection murmur, heard best over the right second intercostal space, with radiation into the right neck. However, high-frequency components may radiate to the apex in calcified aortic valves, and this phenomenon is called the Gallavardin phenomenon. The murmur becomes softer in LV failure and when there is a fall of stroke volume.

Evaluation

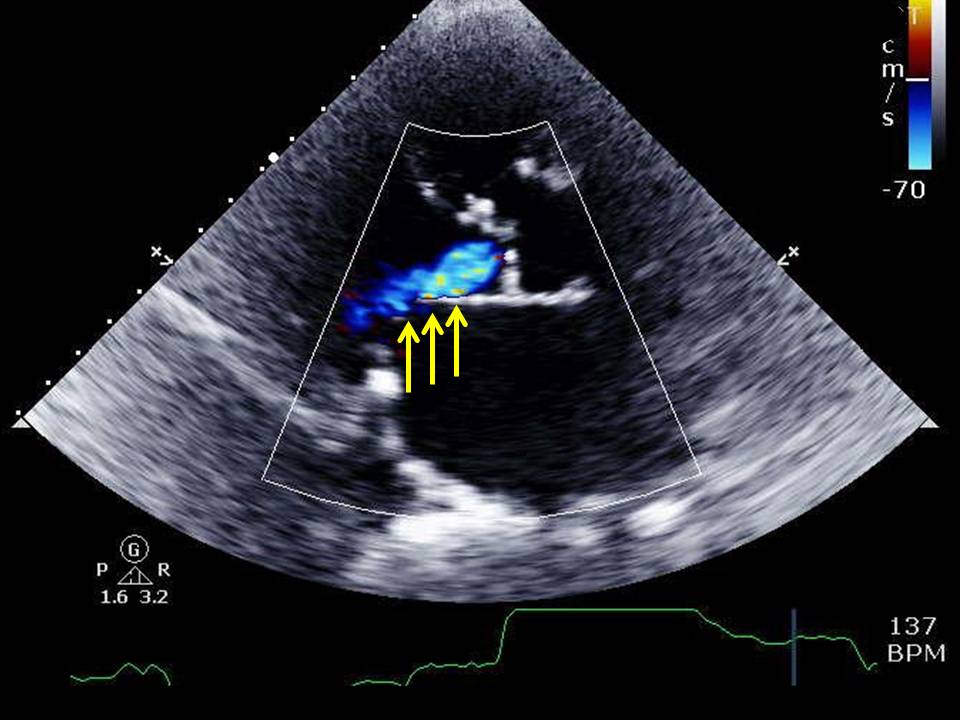

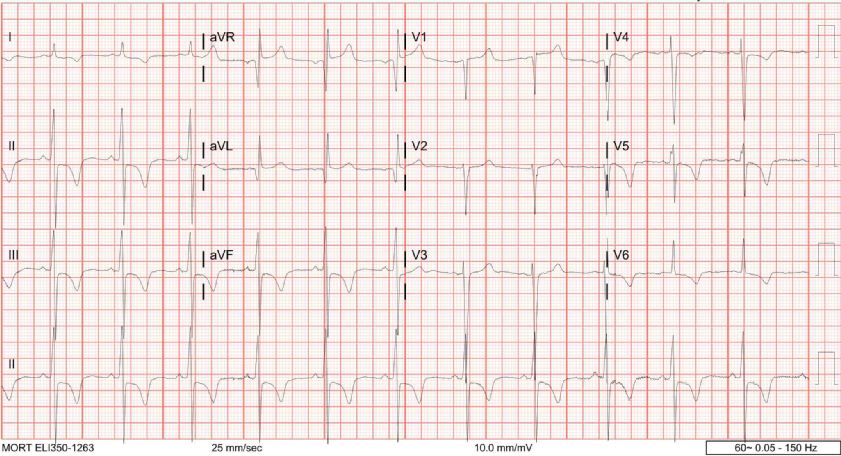

Echocardiography remains the standard approach method to evaluate and follow-up patients with aortic stenosis and stratify them for surgery. It allows imaging of the valve anatomy and the severity of valve calcification and can also allow direct imaging of the orifice area.[20] A more sensitive measure of LV function predicting adverse events, including mortality, is the longitudinal systolic strain imaging.[21][22][23][24] Exercise testing helps in unmasking symptoms in asymptomatic patients, but it should be avoided in symptomatic patients.[25] Cardiac computed tomography (CT) use is expanding in patients with calcific aortic valve disease. It is used when all the non-invasive tests are inconclusive. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can assess LV mass, function, and volume when it cannot be obtained readily in echocardiography.

Treatment / Management

Studies have shown that medical therapy does not significantly affect disease progression in aortic stenosis.[16][26][17]. Aortic valve replacement (AVR) is superior to medical therapy in severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, as proven in observational studies and randomized control trials. As hypertension accompanies the disease most of the time, it is understandable that there may be some reluctance in treating hypertension in this subset of patients as aortic stenosis is known to be a condition with fixed afterload. Vasodilation would not be offset by an increase in stroke volume. However, studies demonstrate that, even in patients with severe aortic stenosis, vasodilation is accompanied by a stroke volume increase. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are preferentially considered. AVR is indicated in patients with heart failure and volume overload, but diuretics can help decrease congestion and provide symptomatic relief before surgery. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty has a modest improvement in the hemodynamic status of the patients. Although it provides a short-term improvement in survival and quality of life, the benefits are not sustained.[27](A1)

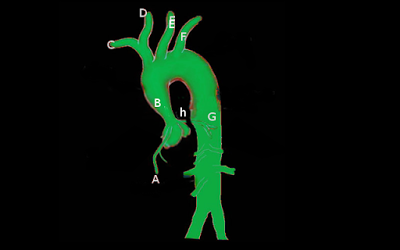

AVR is recommended in adults with symptomatic aortic stenosis, even if the symptoms are mild. It is also recommended in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis with (1) LV ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 50%, (2) who are undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or any other form of heart surgery, (3) Abnormal exercise treadmill test, (4) peak velocity greater than 5 m/sec and mean pressure gradient greater than 60, and (5) annual progression of peak velocity of greater than 0.3 m/s/year.[28][17][29] AVR can be with a surgical or transcatheter approach.[30] Symptoms such as exertional dyspnea and angina are relieved in most of the patients, and a majority will experience an increase in exercise tolerance. LVEF often improves after the surgery, but longitudinal strain might still be impaired.[31] The operative mortality in surgical AVR is about 3.2% in patients undergoing isolated AVR.[32][33] It is less than 1% in patients aged less than 70 and having minimal comorbidities. Advanced age should not be considered a contraindication to the surgery, and 30-day mortality is about 4.2%. Transcatheter AVR has transformed the treatment of patients in calcific aortic stenosis over the last decade. It was initially shown to be superior to medical therapy in patients who are not candidates for surgery. But later, it turned out to be superior to the surgical AVR in high-risk and also intermediate-risk patients. The long-term durability of the procedure is yet to be determined. The most common approach used is the transfemoral approach, especially as there is a progressive decrease in the sheath size. A heart valve team of cardiac surgeons, interventional cardiologists, clinical and imaging experts in valve disease, as well as nurses, anesthetists, and geriatricians, as needed, are essential to recommend the choice of surgical AVR versus transcatheter AVR, given the complexity of the issues. Guidelines recommend AVR for aortic stenosis patients depending on the stage of the condition (image 3) and other factors. Recommendations for considering AVR are explained in detail in image 1.[34] The choice of intervention applies to both surgical AVR and transcatheter AVR. The choice of proceeding with surgical AVR or transcatheter AVR, including multiple factors and is shown in images 1 and 3.[35] (A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The majority of symptoms, such as syncope and angina, overlap with other disease processes, and consequently, the diagnosis can be missed in an acute setting. Cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease contribute to most of these. Exertional dyspnea can also be caused by non-cardiac conditions like pulmonary disease. Diagnosis can be challenging, but the standard pulmonary function tests and cardiopulmonary exercise testing can help differentiate between the conditions. Other causes of ejection systolic murmur with or without LV outflow obstruction include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic sclerosis, and subvalvular stenosis. Subvalvular stenosis can occur from a variety of fixed lesions and can have a dynamic component. A high frequency of supravalvular stenosis occurs in Williams syndrome. A majority of patients have an hourglass deformity with constriction of a thickened ascending aorta at the superior aspect of the sinus of Valsalva.

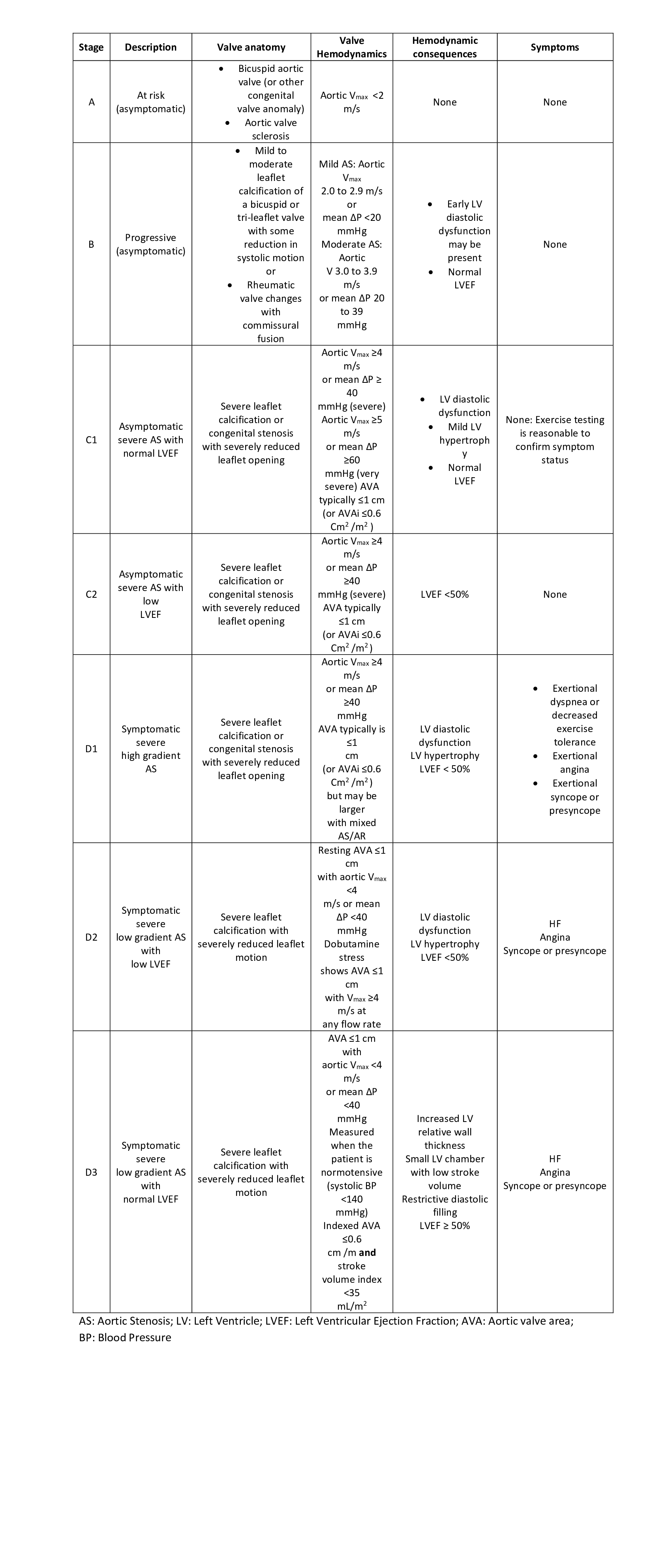

Staging

Stages of the condition include asymptomatic and symptomatic stages taking into consideration the valve hemodynamics. Stages are shown in image 2.[35]

Prognosis

In asymptomatic patients, repeat imaging is typically performed every 3 to 5 years for mild, 1 to 2 years for moderate, and 6 to 12 months for severe aortic stenosis unless they become symptomatic.[35][29] It is difficult to predict the rate of progression of aortic stenosis as it is highly variable. However, older age, severe leaflet calcification, hypertension, obesity, smoking, hyperlipidemia, renal insufficiency, metabolic syndrome, elevated circulating levels of lipoprotein A, and increased activity of lipoprotein-A are associated with rapid hemodynamic regression.[36][37][16] Doppler aortic jet velocity is the strongest predictor of symptom progression in asymptomatic patients.[38][39] Prognosis remains excellent in these patients once moderate to severe aortic stenosis, provided the patient is asymptomatic.[40] Lack of contractile reserve in patients with low-flow, low-gradient, low EF aortic stenosis, very elevated BNP, frailty, very low mean gradient (less than 20 mm Hg), oxygen-dependent lung disease, advanced renal dysfunction, and very high STS score are the factors useful for risk stratification in predicting symptom onset and event-free survival in symptomatic patients. When stenosis severity is moderate or symptoms are equivocal, an elevated BNP level can be helpful, but its role in disease progression has not been fully defined.[41] Survival is poor in symptomatic patients, even while the symptoms are mild, unless the outflow obstruction is relieved. Average survival without AVR is only about 1 to 3 years after the symptom onset.[42][43][38]

Complications

- Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis patients are at a high risk of sudden death. Hence, these patients need to be promptly referred for AVR. Although sudden death is common in symptomatic patients, it can occasionally occur in asymptomatic patients as well.

- Heart failure is one of the most common complications of aortic stenosis. Most patients will have left ventricular hypertrophy with normal systolic function. Diastolic dysfunction develops secondary to hypertrophy and fibrosis and often persists even after AVR. However, some patients can present with systolic dysfunction secondary to the afterload mismatch, resulting in a low ejection fraction.

- Pulmonary hypertension due to chronic elevation in LV diastolic filling pressure. Another complication associated with aortic stenosis is conduction abnormalities. They occur due to hypertrophy, calcium extension from the valve to the interventricular septum, or existing heart disease.

- Patients with aortic stenosis are also at an increased risk for infective endocarditis, particularly patients with the bicuspid aortic valve.

- They are also at increased risk of bleeding, especially GI bleeding, due to acquired von Willebrand syndrome.

- Cerebral or systemic emboli can occur due to calcific emboli from the valve.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is necessary to develop and implement effective postoperative education approaches, to be mindful of the results of the strategy, and to provide a dose of educational interventions. Understanding the patient characteristics that predict poor outcomes is important. Doctors and nurses have a critical function in educating patients. Educating asymptomatic patients about the development of potential symptoms is crucial for early intervention. The individualization of content, the usage of digital platforms for dissemination, the availability of one-on-one instruction, and the enhancement in educational and health performance in various sessions have demonstrated positive results. Patients have the benefits and downsides of each intervention reviewed in detail to make an informed decision. They also need to be educated regarding wound dressing and watching for signs of infection in surgical AVR. They should be educated regarding the warning signs if the doctor or nurse needs to be informed. Athletes and women with the desire to become pregnant have to be educated about limiting physical activity and treating the condition before conceiving, respectively. Nutrition, medications, and physical exercise guidelines need to be communicated to the individual to enhance compliance and results.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional treatment will involve an integrated care system combined with an evidence-based approach to manage and evaluate all joint activities. [Level 1]

In the event of surgical AVR, an interprofessional team utilizing a systematic, coordinated postoperative treatment plan would help deliver the best results possible. The function of nursing care, especially in the case of surgical wound infections, can not be underestimated. If the patient wants to be discharged home with a drain, consultation with a social worker and community nurses may be needed. In the event of deep vein thrombosis with long-term immobility in the hospital, physical therapy might be required. Although cardiothoracic surgeons, interventional cardiologists, and anesthesiologists perform primary roles during surgical and percutaneous AVR, cardiologists and intensivists in critical care play an important role in pre and postoperative treatment. Cardiovascular, operating room and critical nurses are integral to care. In the case of wound infection, the pharmacist must ensure that the patient is receiving the correct analgesics, antiemetics, and antibiotics, while the nurses play a crucial function in tracking vital signs, pre and postoperative care, and patient awareness. Patients undergoing transcatheter AVR have to be thoroughly evaluated for anatomical challenges and comorbidities that may affect the management strategy. Post-procedural monitoring of anticoagulation and prophylaxis for bacterial endocarditis for high-risk procedures is essential.

In conclusion, aortic stenosis can be caused by a congenitally abnormal valve or other acquired conditions such as rheumatic heart disease. Patients will have a prolonged asymptomatic period before developing symptoms such as chest pain, exertional dyspnea, or fatigue. Mortality drastically increases after the development of symptoms. Indications for AVR are based on the status of symptoms, LVEF, and other cardiac surgery indications. Surgical AVR and transcatheter AVR are the mainstays of treatment. [Oxford CEBM Level of Evidence - 1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Video to Play)

References

Nkomo VT,Gardin JM,Skelton TN,Gottdiener JS,Scott CG,Enriquez-Sarano M, Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet (London, England). 2006 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 16980116]

Généreux P,Stone GW,O'Gara PT,Marquis-Gravel G,Redfors B,Giustino G,Pibarot P,Bax JJ,Bonow RO,Leon MB, Natural History, Diagnostic Approaches, and Therapeutic Strategies for Patients With Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 27049682]

Turina J,Hess O,Sepulcri F,Krayenbuehl HP, Spontaneous course of aortic valve disease. European heart journal. 1987 May [PubMed PMID: 3609042]

Pellikka PA,Nishimura RA,Bailey KR,Tajik AJ, The natural history of adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1990 Apr [PubMed PMID: 2312954]

Pai RG,Kapoor N,Bansal RC,Varadarajan P, Malignant natural history of asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: benefit of aortic valve replacement. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006 Dec [PubMed PMID: 17126122]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVaradarajan P,Kapoor N,Bansal RC,Pai RG, Clinical profile and natural history of 453 nonsurgically managed patients with severe aortic stenosis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006 Dec [PubMed PMID: 17126120]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNishimura RA,Otto CM,Bonow RO,Carabello BA,Erwin JP 3rd,Fleisher LA,Jneid H,Mack MJ,McLeod CJ,O'Gara PT,Rigolin VH,Sundt TM 3rd,Thompson A, 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 28315732]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRoss J Jr,Braunwald E, Aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1968 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 4894151]

Kiani AN,Fishman EK,Petri M, Aortic valve calcification in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006; [PubMed PMID: 17211993]

Senechal M,Germain DP, Fabry disease: a functional and anatomical study of cardiac manifestations in 20 hemizygous male patients. Clinical genetics. 2003 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 12519371]

Umana E,Ahmed W,Alpert MA, Valvular and perivalvular abnormalities in end-stage renal disease. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2003 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 12695729]

d'Arcy JL,Coffey S,Loudon MA,Kennedy A,Pearson-Stuttard J,Birks J,Frangou E,Farmer AJ,Mant D,Wilson J,Myerson SG,Prendergast BD, Large-scale community echocardiographic screening reveals a major burden of undiagnosed valvular heart disease in older people: the OxVALVE Population Cohort Study. European heart journal. 2016 Dec 14; [PubMed PMID: 27354049]

Osnabrugge RL,Mylotte D,Head SJ,Van Mieghem NM,Nkomo VT,LeReun CM,Bogers AJ,Piazza N,Kappetein AP, Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Sep 10; [PubMed PMID: 23727214]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCoffey S,Cox B,Williams MJ, The prevalence, incidence, progression, and risks of aortic valve sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Jul 1; [PubMed PMID: 24814496]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRoberts WC,Ko JM, Frequency by decades of unicuspid, bicuspid, and tricuspid aortic valves in adults having isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, with or without associated aortic regurgitation. Circulation. 2005 Feb 22; [PubMed PMID: 15710758]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLindman BR,Clavel MA,Mathieu P,Iung B,Lancellotti P,Otto CM,Pibarot P, Calcific aortic stenosis. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2016 Mar 3; [PubMed PMID: 27188578]

Lindman BR,Bonow RO,Otto CM, Current management of calcific aortic stenosis. Circulation research. 2013 Jul 5; [PubMed PMID: 23833296]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarabello BA,Paulus WJ, Aortic stenosis. Lancet (London, England). 2009 Mar 14; [PubMed PMID: 19232707]

Loscalzo J, From clinical observation to mechanism--Heyde's syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Nov 15; [PubMed PMID: 23150964]

Baumgartner H,Hung J,Bermejo J,Chambers JB,Evangelista A,Griffin BP,Iung B,Otto CM,Pellikka PA,Quiñones M, Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2009 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 19130998]

Kearney LG,Lu K,Ord M,Patel SK,Profitis K,Matalanis G,Burrell LM,Srivastava PM, Global longitudinal strain is a strong independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging. 2012 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 22736713]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLafitte S,Perlant M,Reant P,Serri K,Douard H,DeMaria A,Roudaut R, Impact of impaired myocardial deformations on exercise tolerance and prognosis in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis. European journal of echocardiography : the journal of the Working Group on Echocardiography of the European Society of Cardiology. 2009 May; [PubMed PMID: 18996958]

Dahl JS,Videbæk L,Poulsen MK,Rudbæk TR,Pellikka PA,Møller JE, Global strain in severe aortic valve stenosis: relation to clinical outcome after aortic valve replacement. Circulation. Cardiovascular imaging. 2012 Sep 1; [PubMed PMID: 22869821]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLancellotti P,Donal E,Magne J,Moonen M,O'Connor K,Daubert JC,Pierard LA, Risk stratification in asymptomatic moderate to severe aortic stenosis: the importance of the valvular, arterial and ventricular interplay. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2010 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 20483891]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMagne J,Lancellotti P,Piérard LA, Exercise testing in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2014 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 24524744]

Otto CM,Prendergast B, Aortic-valve stenosis--from patients at risk to severe valve obstruction. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Aug 21; [PubMed PMID: 25140960]

Kapadia S,Stewart WJ,Anderson WN,Babaliaros V,Feldman T,Cohen DJ,Douglas PS,Makkar RR,Svensson LG,Webb JG,Wong SC,Brown DL,Miller DC,Moses JW,Smith CR,Leon MB,Tuzcu EM, Outcomes of inoperable symptomatic aortic stenosis patients not undergoing aortic valve replacement: insight into the impact of balloon aortic valvuloplasty from the PARTNER trial (Placement of AoRtic TraNscathetER Valve trial). JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2015 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 25700756]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNishimura RA,Otto CM,Bonow RO,Carabello BA,Erwin JP 3rd,Guyton RA,O'Gara PT,Ruiz CE,Skubas NJ,Sorajja P,Sundt TM 3rd,Thomas JD, 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 10; [PubMed PMID: 24589853]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVahanian A,Alfieri O,Andreotti F,Antunes MJ,Barón-Esquivias G,Baumgartner H,Borger MA,Carrel TP,De Bonis M,Evangelista A,Falk V,Iung B,Lancellotti P,Pierard L,Price S,Schäfers HJ,Schuler G,Stepinska J,Swedberg K,Takkenberg J,Von Oppell UO,Windecker S,Zamorano JL,Zembala M, Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). European heart journal. 2012 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 22922415]

Bonow RO,Leon MB,Doshi D,Moat N, Management strategies and future challenges for aortic valve disease. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Mar 26; [PubMed PMID: 27025437]

Kafa R,Kusunose K,Goodman AL,Svensson LG,Sabik JF,Griffin BP,Desai MY, Association of Abnormal Postoperative Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain With Outcomes in Severe Aortic Stenosis Following Aortic Valve Replacement. JAMA cardiology. 2016 Jul 1; [PubMed PMID: 27438331]

Shahian DM,O'Brien SM,Filardo G,Ferraris VA,Haan CK,Rich JB,Normand SL,DeLong ER,Shewan CM,Dokholyan RS,Peterson ED,Edwards FH,Anderson RP, The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 3--valve plus coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2009 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 19559824]

O'Brien SM,Shahian DM,Filardo G,Ferraris VA,Haan CK,Rich JB,Normand SL,DeLong ER,Shewan CM,Dokholyan RS,Peterson ED,Edwards FH,Anderson RP, The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 2--isolated valve surgery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2009 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 19559823]

Nishimura RA,Otto CM,Bonow RO,Carabello BA,Erwin JP 3rd,Guyton RA,O'Gara PT,Ruiz CE,Skubas NJ,Sorajja P,Sundt TM 3rd,Thomas JD, 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 10; [PubMed PMID: 24589852]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNishimura RA,Otto CM,Bonow RO,Carabello BA,Erwin JP 3rd,Fleisher LA,Jneid H,Mack MJ,McLeod CJ,O'Gara PT,Rigolin VH,Sundt TM 3rd,Thompson A, 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017 Jun 20; [PubMed PMID: 28298458]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCapoulade R,Chan KL,Yeang C,Mathieu P,Bossé Y,Dumesnil JG,Tam JW,Teo KK,Mahmut A,Yang X,Witztum JL,Arsenault BJ,Després JP,Pibarot P,Tsimikas S, Oxidized Phospholipids, Lipoprotein(a), and Progression of Calcific Aortic Valve Stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015 Sep 15; [PubMed PMID: 26361154]

Capoulade R,Mahmut A,Tastet L,Arsenault M,Bédard É,Dumesnil JG,Després JP,Larose É,Arsenault BJ,Bossé Y,Mathieu P,Pibarot P, Impact of plasma Lp-PLA2 activity on the progression of aortic stenosis: the PROGRESSA study. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2015 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 25499129]

Stewart RA,Kerr AJ,Whalley GA,Legget ME,Zeng I,Williams MJ,Lainchbury J,Hamer A,Doughty R,Richards MA,White HD, Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function assessed by tissue Doppler imaging and outcome in asymptomatic aortic stenosis. European heart journal. 2010 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 20513730]

Capoulade R,Le Ven F,Clavel MA,Dumesnil JG,Dahou A,Thébault C,Arsenault M,O'Connor K,Bédard É,Beaudoin J,Sénéchal M,Bernier M,Pibarot P, Echocardiographic predictors of outcomes in adults with aortic stenosis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2016 Jun 15; [PubMed PMID: 27048774]

Dal-Bianco JP,Khandheria BK,Mookadam F,Gentile F,Sengupta PP, Management of asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008 Oct 14; [PubMed PMID: 18929238]

Clavel MA,Malouf J,Michelena HI,Suri RM,Jaffe AS,Mahoney DW,Enriquez-Sarano M, B-type natriuretic peptide clinical activation in aortic stenosis: impact on long-term survival. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 May 20; [PubMed PMID: 24657652]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBach DS,Siao D,Girard SE,Duvernoy C,McCallister BD Jr,Gualano SK, Evaluation of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who do not undergo aortic valve replacement: the potential role of subjectively overestimated operative risk. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2009 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 20031890]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLeon MB,Smith CR,Mack M,Miller DC,Moses JW,Svensson LG,Tuzcu EM,Webb JG,Fontana GP,Makkar RR,Brown DL,Block PC,Guyton RA,Pichard AD,Bavaria JE,Herrmann HC,Douglas PS,Petersen JL,Akin JJ,Anderson WN,Wang D,Pocock S, Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Oct 21; [PubMed PMID: 20961243]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence