Introduction

Skin is part of the integumentary system and considered to be the largest organ of the human body. There are three main layers of skin: the epidermis, the dermis, and the hypodermis (subcutaneous fat). The focus of this topic is on the epidermal and dermal layers of skin. Skin appendages such as sweat glands, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands are reviewed in-depth elsewhere.[1]

Structure

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure

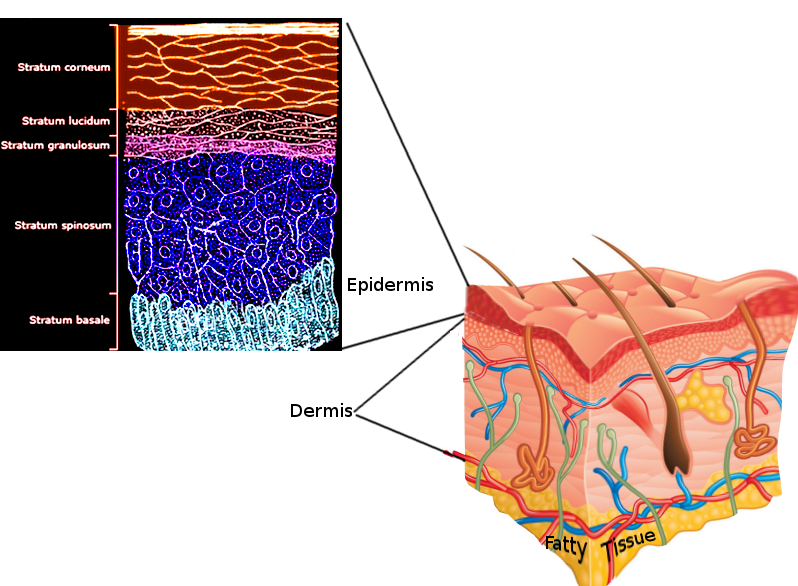

The first and outermost layer of skin is the epidermis. The epidermis is a stratified squamous epithelium that contains four to five layers depending on its location:

- Stratum Basalis (Basal cell layer): This layer is deepest and closest to the dermis. It is mitotically active and contains melanocytes, a single row of keratinocytes, and stem cells. Melanocytes are the cell type responsible for producing melanin, a substance that gives our skin its color. Keratinocytes from this layer evolve and mature as they travel outward/upward to create the remaining layers.

- Stratum Spinosum (prickle cell layer): This layer compromises most of the epidermis and contains several layers of cells connected by desmosomes. These desmosomes allow cells to remain tightly bound to one another and resemble "spines" architecturally.

- Stratum Granulosum (granular cell layer): This layer contains several layers of cells that contain lipid-rich granules. In this layer, cells begin to immortalize and lose their nuclei, as they move away from the nutrients located in the deeper tissue.

- Stratum Lucidum: This layer only exists in the thick skin of soles and palms and consists of mostly immortalized cells.

- Stratum Corneum (keratin layer): This keratinized layer serves as a protective overcoat and is the outermost layer of the epidermis. Due to keratinization and lipid content, this layer allows for the regulation of water loss by preventing internal fluid evaporation.[2]

Deep to the epidermis lies the dermis. It is a thick layer of connective tissue consisting of collagen and elastin which allows for skin’s strength and flexibility, respectively. The dermis also contains nerve endings, blood vessels, and adnexal structures such as hair shafts, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands. The apical layer of dermis folds to form papillae that extend into the epidermis like tiny finger-like projections and is referred to as the papillary dermis, while the lower layer of the dermis is referred to as the reticular dermis.

The hypodermis is the third and deepest layer consisting mainly of adipose tissue.

Function

There are four main functions of the skin: sensation, thermoregulation, protection, and metabolism [3]

- Sensation: The skin contains many types of different receptors that sense pain, temperature, pressure, and touch.

- Thermoregulation: Hair and sweat glands aid in the regulation of body temperature to maintain homeostasis

- Protection: The skin serves as the barrier between the inside and outside of the body against infection, chemical stress, thermal stress, and UV light

- Metabolism: Adipose tissue in the hypodermis is vital in the production of Vitamin D and lipid storage.

Tissue Preparation

After completion of a skin biopsy, the tissue is generally processed and sectioned for analysis with light microscopy. Skin tissue processing methods vary among laboratories; however, the paraffin technique is the most common. The standard steps for this process are fixation, dehydration, clearing, and paraffin infiltration. Fresh tissue is generally stored and transferred in 10% neutral buffered formalin fixative, which helps maintain tissue architecture by cross-linking lysine residues. Specimens get embedded in wax before mounting on glass slides for viewing. However, wax is not soluble in water or alcohol; therefore the specimens must undergo dehydration first. Alcohol dehydration is used to remove water from the sample. Alcohol is then removed by xylene as they are miscible in a process referred to as "clearing." The tissue is placed in a warm paraffin wax which replaces the spaces which water previously occupied. After the blocks have cooled, they are cut into thin slices, rehydrated with water, and then stained with stains such as hematoxylin and eosin. The amount of time for this process is dependent on tissue size, temperature, and reagents used.

Other techniques to make sections for light microscopy are frozen sections and semithin sections. Frozen sections are achieved by freezing tissue with liquid nitrogen and cutting it with a cold knife. This technique is faster than the paraffin technique. Semithin sections are used to see fine detail and are achieved by embedding sections in epoxy, allowing for thinner slices to be cut.

Specimens that require immunofluorescence undergo preservation in Michel's or Zeus solution rather than formalin.

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

Langerhans cell and melanocytes contain S-100.[4] Immunofluorescence for antibodies against hemidesmosomes and desmosomes are commonly used to differentiate between blistering dermatoses like pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid. Immunomapping may be helpful in distinguishing heritable blistering disorders.

Microscopy, Light

Different layers of the epidermis are visible by examining sectioned epidermal tissue under hematoxylin and eosin staining under light microscopy:

- Stratum Basalis: characterized by cuboidal or low columnar cells with basophilic cytoplasm and melanocytes. Melanocytes present as rounded cell bodies with clear cytoplasm and slender cytoplasmic processes

- Stratum Spinosum: characterized by desmosomes attaching polyhedral shaped keratinocytes with a round to oval nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Desmosome junctions appear as spines between cells

- Stratum granulosum: characterized by keratinocytes with dense, ovoid, and basophilic keratohyalin granules

- Stratum lucidum: characterized by a thin homogenous eosinophilic zone that is difficult to identify in H&E sections

- Stratum corneum: characterized by keratin in anucleate cells in a basket weave pattern

The dermis is more visible with a Verhoeff’s stain. The interlacing collagen appears in red with elastic fibers in black.[5] Blood vessels are surrounded by round, clear cells with well-defined borders named glomus cells.

Microscopy, Electron

Use of electron microscopy of skin, though limited, can be useful in identifying certain cell types such as Langerhans cells. These cells are characterized by Birbeck granules that appear as tennis rackets due to zipper like cross striations with a bulbous ending.

Pathophysiology

Melanocytes are neural crest-derived cells that sit in the stratum basalis of skin and hair follicles. These cells are responsible for the production of melanin from tyrosine. Melanin is a pigment that serves to protect DNA from UV radiation. Different skin tones are due to differences in the amount of melanin, size, and density once transferred from melanocytes to keratinocytes via melanosomes, rather than the number of melanocytes. Destruction and unregulated proliferation of melanocytes lead to various pathologies such as vitiligo and melanoma.[6]

Langerhans cells are specialized dendritic cells found predominantly in the skin. Much like macrophages, these cells are derived from bone marrow monocytes and are capable of antigen presentation.[7] Malignant proliferation of these cells are very rare and lead to a variety of diseases such grouped as Langerhans cell histiocytoses.

Parakeratosis refers to corneocytes in the stratum corneum with retained nuclei. Though normal is some parts of the skin, this is abnormal is most. Parakeratosis is a sign of increased cell turnover and can present in disorders such as psoriasis.[8]

Hyperkeratosis refers to the thickening of the stratum corneum due to an abnormal increase in keratin. It is often present in a condition like eczema, warts, and corns.

Clinical Significance

There is a large amount of pathology associated with skin because of its vastness, diverse cell types, and constant proliferation.

- Inflammatory dermatoses include diseases such as eczema, psoriasis, acne vulgaris, lichen planus, and contact dermatitis

- Blistering dermatoses include conditions such as pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, and dermatitis herpetiformis

- Epithelial tumors include neoplasms such as basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and seborrheic keratosis

- Disorders of pigmentation and melanocytes include diseases such as vitiligo, albinism, nevus, and melanoma

- Infectious disorders include impetigo, cellulitis, verruca, and molluscum contagiosum

- Metabolic disorders may show signs in the skin as the epidermis is a rapidly cycling tissue

Media

References

Brown TM, Krishnamurthy K. Histology, Hair and Follicle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422524]

Murphrey MB, Miao JH, Zito PM. Histology, Stratum Corneum. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020671]

Sahle FF, Gebre-Mariam T, Dobner B, Wohlrab J, Neubert RH. Skin diseases associated with the depletion of stratum corneum lipids and stratum corneum lipid substitution therapy. Skin pharmacology and physiology. 2015:28(1):42-55. doi: 10.1159/000360009. Epub 2014 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 25196193]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXia J, Wang Y, Li F, Wang J, Mu Y, Mei X, Li X, Zhu W, Jin X, Yu K. Expression of microphthalmia transcription factor, S100 protein, and HMB-45 in malignant melanoma and pigmented nevi. Biomedical reports. 2016 Sep:5(3):327-331 [PubMed PMID: 27602212]

Kanitakis J. Anatomy, histology and immunohistochemistry of normal human skin. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2002 Jul-Aug:12(4):390-9; quiz 400-1 [PubMed PMID: 12095893]

Birlea SA. S100B: Correlation with Active Vitiligo Depigmentation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2017 Jul:137(7):1408-1410. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.03.021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28647026]

Yousef H, Alhajj M, Fakoya AO, Sharma S. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262154]

Ruchusatsawat K, Wongpiyabovorn J, Protjaroen P, Chaipipat M, Shuangshoti S, Thorner PS, Mutirangura A. Parakeratosis in skin is associated with loss of inhibitor of differentiation 4 via promoter methylation. Human pathology. 2011 Dec:42(12):1878-87. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.02.005. Epub 2011 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 21663940]