Introduction

Infarcts involving the territory of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) are uncommon, accounting for a considerably small share of the total number of ischemic infarcts. The risk factors and etiology of strokes in this vascular territory are largely the same as for the other principal cerebral arteries including hypertension, dyslipidemias, diabetes mellitus, smoking, atherosclerosis, and cardioembolism. However, it is possible that the peculiar manifestations of its clinical syndromes and the suspicion that many infarcts in this arterial territory are silent could result in the underdiagnosis of strokes involving the ACA or its branches.[1]

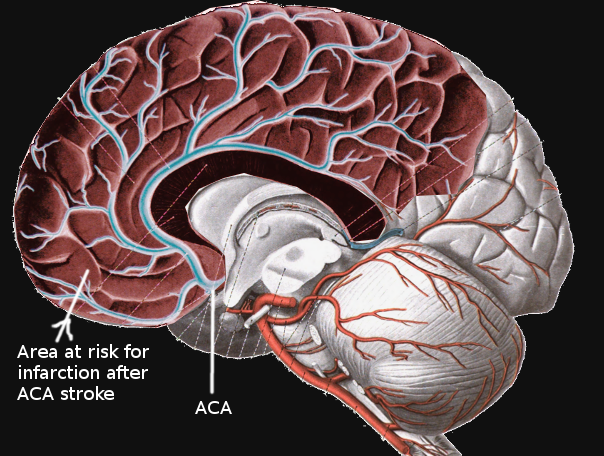

The ACA emerges from the anterior clinoid segment of the internal carotid artery. It then continues anteromedially towards the longitudinal fissure. Near this point, the anterior communicating artery (ACoA) forms, creating an anastomosis between both ACA’s. Each ACA then advances between the two cerebral hemispheres and over the callosal sulcus in a posterior direction towards the parieto-occipital sulcus. Superficial and deep branches emerge along its course. These include Heubner’s, orbitofrontal, frontopolar, anterior internal frontal, middle internal frontal, posterior internal frontal, paracentral, superior parietal, inferior parietal, pericallosal, and callosomarginal arteries. The ACA itself often divides into five segments, usually labeled as A1 through A5, or as proximal (A1), ascending (A2, A3), and horizontal segments.[2][3][4] A significant feature of the ACA is its robust anastomotic complex; this may account for the low rate of infarcts in this vascular distribution.[1] Notably, infarctions simultaneously affecting both cerebral hemispheres may also be present among ACA stroke cases. These are rare and characteristically occur because of clinically significant anatomical variations affecting both ACA's at any point along its course. The most recognizable patterns are the azygos, bihemispheric, and ACA with hypoplastic or absent A1 segment.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking are known risk factors of the cardiovascular disease frequently found in stroke patients. These underlie varied processes which ultimately result in atherosclerosis of large and small arteries. Atrial fibrillation is another significant risk factor, its frequency surpassing that of dyslipidemia among patients with ACA stroke in one study.[6]

Atherosclerosis is a primary cause of ischemic stroke. One clinical imaging study of anterior cerebral artery infarction mechanisms concluded that atherosclerotic disease-related stroke mechanisms in the ACA were similar to those associated with middle cerebral artery (MCA) atherosclerosis. Atherosclerotic large vessel disease frequently results in stroke secondary to either local branch occlusion by plaque, artery-to-artery embolism, and in situ thrombosis, with the latter considered as being the most prevalent in ACA infarction.[3][7] Atherosclerosis is the most frequently reported etiology among studies in patients of Asian origin.[4][7]

Cardiac embolism from different sources, including atrial fibrillation, intracardiac thrombus, valve disease, and tumors are other significant causes of ACA infarction. Some reports suggest that cardiac emboli are more frequently the cause of ACA as compared to MCA and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) infarcts.[4][6] A hypoplastic or absent A1 segment is thought to facilitate embolic strokes due to increased vascular flow through the unique proximal section that branches off distally into the bilateral ACA’s.[5]

Another significant mechanism of ACA stroke is arterial dissection. While rarely reported on Western populations, other sources refer to a high prevalence among Japanese patients. Those with stroke secondary to arterial dissection also tend to be younger.[4][8]

Less common mechanisms have been described, including vasculitis and coagulopathic states. Vasospasm is another cause. Reported triggers include subarachnoid hemorrhage and pituitary apoplexy. This mechanism has correlated with both unilateral and bilateral ACA infarcts. There are reported cases with unknown etiology in some case series.[1][3][6][7][8][9]

Distal vessel occlusion secondary to lost or fragmented thrombi associated with the use of intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy is another potential mechanism of ACA stroke. One study evaluating the frequency of ACA embolism in 105 patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy of occlusions of the M1 segment of the MCA identified 12 new ACA emboli (11.4% of studied cases). ACA infarcts were identified on follow-up imaging in 5.7% of patients. The significance of this particular mechanism of infarction lies in its potential for adverse outcomes secondary to distal occlusions after an otherwise effective recanalization of an affected vessel.[10]

Epidemiology

Infarctions of the anterior cerebral artery and its branches are infrequent, accounting for 0.3% to 4.4% of stroke cases reported in different series. Overall, the studies show that males are affected more frequently than females. The mean patient age reported in some ACA infarct studies ranged between 59 and 74.4 years of age. One study addressed the increased prevalence of ACA infarcts among those over age 85, which was similar to findings in other stroke studies including all vascular territories. Left-sided ACA infarcts are more frequent.[1][3][6][7][11]

History and Physical

Patients presenting with an acute stroke of the anterior cerebral artery will have varied presentations depending on whether the ACA itself or any of its branches are affected. The size of the infarct will also influence the clinical presentation. Most commonly, patients will present with motor deficits characteristically involving the lower extremity contralateral to the infarct site. This finding is present in 86.3% to 90% of patients.[3][6][7] Heubner’s artery and medial striate artery infarcts are associated with contralateral face and arm weakness, resulting from damage to the anteromedial caudate nucleus, anterior limb of the internal capsule, and anterior perforated substance.[4] A syndrome composed of homolateral ataxia and crural hemiparesis has been reported as another distinct phenomenon of ACA infarction attributed to damage of both the corticopontine fibers and the lower limb strip.[12] There are three patient case reports of isolated unilateral axial weakness. These cases attributed the deficit to hypotonia of the paravertebral muscles secondary to strokes involving the primary motor cortex on the precentral gyrus.[13] Other motor disorders related to ACA infarction include hypometria, bradykinesia, global akinesia, loss of reciprocal coordination, parkinsonian gait, tremor, dystonia, and motor neglect.[11][14] The alien hand syndrome, in which one hand appears to be independent, and which the patient cannot control, may present in infarcts involving the corpus callosum, frontal lobe, or posterolateral parietal lobe.[15]

Isolated sensory deficits are less common. Out of 81 patients in the paper by Kang et al. with the performance of reliable sensory testing, identifiable deficits appeared in 20 (25%) subjects. When present, they always correlate with a weak extremity.[7] Conversely, none of the patients in the study by Nagaratnam et al. had any significant impairment to touch, pain, or discriminative sensory modalities.[11] One case of ACA infarct in the lower limb sensory homunculus has been reported, presenting with sensory disturbances exclusively.[16]

Abulia, agitation, motor perseveration, memory impairments, emotional lability, or incontinence, as well as anosognosia, are among the neuropsychologic features associated with ACA infarction.[7] Altered consciousness and speech disorders have been identified as independent variables of ACA infarction when compared to MCA infarcts in one study where 43.1% of patients had this finding.[6] Speech disorders associated with ACA infarction include transcortical motor aphasia, with reports of it occurring following a period of muteness. Damage to the supplementary motor area correlates with these disorders. Another speech disorder found is transcortical mixed aphasia.[3][11]

Bilateral ACA infarction is rare. One study involving 48 patients with ACA infarction had only 2 cases, with a mean age at presentation of 40.[3] The most consistent findings in one study including patients with bilateral ACA infarction were frontal disinhibition signs such as enhanced glabellar tap, utilization behavior, forced grasping, snout, and other primitive reflexes. The prefrontal cortex was not always affected in these cases.[14] Paraparesis and akinetic mutism were also documented in the context of bilateral ACA stroke.[3] One case report documented a presentation consisting of right hemiballismus and involuntary left-hand masturbation.[17]

Headaches also correlate with ACA infarction, specifically in instances of arterial dissection.[4]

Evaluation

Once an acute ischemic stroke is suspected, the standard evaluation includes performing routine airway, breathing, and circulation assessment, checking blood glucose, performing a validated stroke severity scale assessment, and an accurate, focused history regarding the time of symptom onset or last known well or at baseline. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a standardized method for quantifiable assessment of stroke symptoms. It is the preferred scoring system, and scores range from 0 to 42. A patient with a higher score on this scale is more likely to be considered disabled; however, the definition of "disabling" depends on age, occupation, underlying life-limiting comorbidities, and advance directives.

The crucial step in the evaluation of stroke patients is to obtain brain imaging to ascertain the type and characteristics of the stroke. In this regard, non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the head is the imaging modality of choice. Ischemic changes may classify as acute, subacute, and chronic, depending on the time in which they present after the onset of stroke. CT scan can also rule out intracranial hemorrhage.[18] If an intracranial hemorrhage is present, aneurysmal rupture should be investigated given its association with arterial vasospasm resulting in a stroke.[3] Anterior cerebral artery strokes could be missed on imaging studies depending on their location or size. One case series found that 37.5% (6 of 16) of ACA infarcts evaluated by CT were identifiable only after using contrast injection or angiography. If the area of hypodensity is small and localized over a sulcus, the infarct could be overlooked.[1][13] Noncontrast head CT should be quickly followed by CT angiography of the head and neck to expedite identification of intracranial large vessel occlusion.

The finding of a hyperdense lesion in the ACA on CT scan aid in the diagnosis of stroke in its acute phase, particularly when it may be otherwise difficult to establish. The frequency of this sign in ACA infarcts is similar to that in the territories of the middle cerebral artery and the posterior circulation.[19]

As in strokes involving other areas of the brain, magnetic resonance imaging is also of critical value in the diagnosis of ACA strokes. MRI with diffusion-weight imaging (DW-MRI) is a highly useful modality, which facilitates the demarcation of ischemic boundaries in the territory of the ACA.[3][18] MR angiography can be a helpful adjunct in the evaluation of stroke mechanisms.[7] The goal of completing a head CT or MRI should be 25 minutes or less after patient arrival.

The National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) established time frame goals in the evaluation of stroke patients: door to physician less than 10 minutes, door to stroke team less than 15 minutes, door to CT scan less than 25 minutes, and door to drug less than 60 minutes.[20]

Along with accurate history and early imaging, laboratory studies including capillary blood glucose, complete blood count with platelets, chemistries, coagulation studies, hemoglobin A1c, lipid panel, and markers of hypercoagulability or inflammation can be useful in identifying the risk factors or establishing the etiology of stroke. The medication checklist is an integral part of the evaluation, specifically the recent use of anticoagulants, as contraindications to thrombolytic therapy should undergo rapid assessment. Cardiac sources of embolism can be evaluated as part of the work-up with an electrocardiogram (EKG) monitoring and echocardiogram.

Treatment / Management

Pulse oximetry can guide the use of supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation greater than 94%. Hyperoxia should be avoided as may be detrimental in stroke. Hypertension is common in an acute ischemic stroke. A low BP is uncommon and may indicate symptoms exacerbation of a previous stroke due to poor perfusion. Blood pressure of 220/120 mmHg should receive treatment. There is a consensus approach of allowing permissive hypertension up to 220/120 mmHg for patients that are not candidates for thrombolysis.[21]

However, for a patient that is a potential candidate for alteplase, an attempt to control BP should be made immediately as the goal BP for initiation of intravenous (IV) alteplase is 185/110 mmHg. Usually, titratable short-acting intravenous hypotensive agents are recommended to avoid dropping the BP too much once the patient is at goal. Hypotensive agents that can be options include labetalol, nicardipine, clevidipine, hydralazine, enalaprilat.[21]

For the patients that present within the therapeutic window, the decision to treat with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen (less than 4.5 hours from symptom onset) or endovascular treatment with mechanical thrombectomy should be made. Initiation of IV alteplase treatment in the 3 to 4.5-hour window is the current recommendation for patients less than 80 years of age, no history of both diabetes mellitus and prior stroke, use of anticoagulants, and NIHSS score of less than 25. Only patients with disabling symptoms are considered eligible for thrombolytic treatment. Eligibility and absolute and relative contraindications should undergo rapid assessment. Randomized controlled trials have shown that intravenous administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (alteplase) decreases functional disability with absolute reduction risk of 7%-13% relative to placebo.[21]

Unfortunately, over half of patients arrive after this time window has closed and are not eligible for thrombolysis. Treatment delays may result from failure to attribute the patient's symptoms to a stroke, and furthermore, the risk of harm increases with time elapsed from symptom onset.[21] This situation could be of particular concern in ACA strokes, given their sometimes atypical presentation.

Endovascular treatment with mechanical thrombectomy (MT) is another proven treatment modality in the management of patients with acute stroke suffering a large vessel occlusion, although treatment efficacy is highly time-dependent. The procedure is available in tertiary hospitals and requires a stroke team with the expertise to use timely imaging and intervention. One study evaluating MT in ACA stroke patients found that while recanalization rates were high, the outcomes were otherwise unsatisfactory. The latter was attributed to larger infarct volumes and longer times to recanalization.[22][23]

New guidelines recommend that in patients with acute ischemic stroke within 6 to 24 hours from last known well and who have large vessel occlusion in the anterior circulation, obtaining CT perfusion (CTP), DW-MRI, or MRI perfusion is recommended to aid in selection for mechanical thrombectomy. However, this is only with the strict application of imaging or other eligibility criteria from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing benefit in selecting patients for MT. The DAWN trial used clinical imaging mismatch (imaging from CTP or DW-MRI and NIHSS scoring) as criteria to select patients with anterior circulation large vessel occlusion (LVO) for MT between 6 to 24 hours from last known well. The trial demonstrated an overall functional benefit at 90 days in the treatment group (modified Rankin score [mRS] score 0 to 2, 49% versus 13%, adjusted difference 33%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 21 to 44; a probability of superiority greater than 0.999). The DEFUSE 3 trial used perfusion core mismatch and maximum core size as criteria in selecting the patient for MT with LVO in anterior circulation 6 to 16 hours from last time seen normal. This trial also showed outcome benefit at 90 days in the treated group (mRS score 0 to 2, 44.6% versus 16.7%, risk ratio [RR] 2.67, 95% CI, 1.60 to 4.48, p greater than 0.0001). DAWN and DEFUSE 3 are the only trials showing a benefit of mechanical thrombectomy greater than 6 hours from symptoms onset. Only criteria from these trials should be viable for patient selection who might benefit from MT.[21] Clinicians should be aware that most of the patients involved in DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials had middle cerebral artery occlusions.

Anterior cerebral artery stroke can occur following an anterior communicating artery aneurysm rupture either due to vasospasm or due to inadvertent surgical clipping of the anterior cerebral artery branches or perforator vessels. Intraoperative indocyanine green video angiography can reduce the complications from improper clipping.[24](B2)

Beyond the acute management of stroke, the use of antihypertensives, dual antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulants, and carotid endarterectomy should be used to prevent recurrent events. Antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulants are not recommended within 24h after alteplase administration. Aspirin is not a recommendation as a substitute for other interventions for acute stroke. Administration of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor is not recommended, and a recent Cochrane review showed that these agents correlated with a high risk of intracranial hemorrhage. Dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) is recommended to start within 24 hours for 21 days in patients with minor stroke for early secondary stroke prevention. The CHANCE trial showed that the primary outcome of a recurrent stroke at 90 days favored dual antiplatelet therapy over aspirin alone (HR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.81, p<0.0001). Ticagrelor over aspirin in acute stroke treatment is not recommended. According to SOCRATES trial with the primary outcome of time to the composite endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI) or death up to 90 days, ticagrelor was not found to be superior to aspirin (hazard ratio [HR] 0.89, 95% CI, 0.78-1.01; p=0.07). However, ticagrelor is a reasonable alternative in patients with contraindication to aspirin. The efficacy of tirofiban and eptifibatide is currently unknown.[20][21]

Optimization of risk factors is essential for secondary prevention of stroke in order to improve outcomes from the principal event.[21]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential of stroke in general, as well as one that involves the anterior cerebral artery, include metabolic, hypoglycemia, infectious (fever, sepsis), cardiovascular (e.g., syncope), migraines, tumors, abscess, neuromuscular, and varied neuropsychiatric conditions. Clinicians should adopt strategies to reduce the likelihood of missing the diagnosis in a narrow time window in stroke cases given the time-sensitive nature of its acute treatment. A suggested approach includes suspecting stroke in the context of acute-onset neurological symptoms, increased clinician awareness of uncommon stroke syndromes, and the performance of a systematic neurological exam to better determine the nature of the problem.[15][25]

Prognosis

In-hospital mortality of anterior cerebral artery stroke patients can range between 0 and 7.8%. This is lower than the 17.3% found for patients with MCA stroke in one of the studies evaluating patients with ACA stroke. Case series show a favorable prognosis for patients, with up to 68% of patients in one series having a modified Rankin scale score of 2 or less at discharge.[3][4][6]

With regards to specific deficits, studies suggest that aphasias from ACA infarcts tend to improve within a short period, in contrast with those resulting from MCA territory lesions. Infarct size has been found to show a poor correlation with functional recovery.[7][11]

One case of akinetic mutism reversal with L-dopa therapy has been reported.[26]

Generally, patients with major neurological deficits have a high risk of poor outcomes, regardless of whether or not alteplase is administered.

Complications

Patients with large infarctions are at high risk of developing brain edema. Early transfer of patients at risk to an institution with neurosurgical expertise should be considered.[21]

Recurrent seizures after stroke should receive therapy with anti-seizure medications; however prophylactic use of these drugs is not recommended.[21]

Complications related to IV alteplase administration are intracranial hemorrhage and angioedema. If the patient develops a headache, nausea, vomiting, new or worsening neurological deficits, cerebral hemorrhage should be suspected; IV alteplase should be discontinued immediately, and stat head CT scan obtained. In case of signs or symptoms of angioedema, maintaining airway patency should be the primary goal. In addition to alteplase discontinuation, IV methylprednisolone and diphenhydramine should be administered. Epinephrine and icatibant, a selective bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist, and plasma-derived C1 esterase inhibitor can be therapeutic considerations.[21]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The recommendation is for early rehabilitation in environments with organized, interprofessional stroke care to improve outcomes for patients with stroke.[21]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with risk factors for stroke including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, and smoking should be educated on the signs of symptoms of strokes. Additionally, they should be encouraged to call 911 if they ever develop stroke symptoms as patients that utilize emergency medical services frequently have better outcomes. Lifestyle modification including weight loss, limiting carbohydrates and sodium in the diet, and tobacco cessation can lower the risk of stroke. Patients that have had a stroke should be made aware of the importance of medication adherence and the consequences of inadequate treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A good outcome from acute ischemic stroke is more likely with early recognition of symptoms of stroke and the involvement of an interprofessional team. Previous studies showed that public education of signs and symptoms of stroke improves stroke recognition, however, data indicates that public knowledge remains poor. Stroke education should target patients, family members, caregivers, empowering them to use the emergency medical system as prehospital delays and door to CT scans are shorter if patients are transported by ambulance. Also, advanced notification of stroke teams by EMS shortens the time to initial evaluation by clinicians and increases the likelihood of alteplase use. The California Acute Stroke Pilot Registry (CASPR) indicates that if patients arrived shortly after onset, the rate of fibrinolytic treatment within 3 hours increased from 4.3% to 28.6%.[21]

Emergency medical services (EMS) systems play a critical role in the optimization of stroke care by using prehospital stroke assessment tools. Once the stroke is suspected it becomes a high priority dispatch and transport to the highest level of care in the shortest time possible is initiated immediately. A focused, accurate history including time of symptom onset or last known well, checking blood glucose levels, obtaining intravenous access, obtaining blood samples are obtainable by EMS in the field or while transporting the patient. Established, specific time frames exist for the EMS to follow and all efforts should be made to avoid unnecessary delays. Notification of the receiving institution before patient arrival is critical for rapid diagnosis and early management. Patients should have transportation to the closest available PCS (Primary Stroke Center) or CSC (Comprehensive Stroke Center) or the most appropriate institution that provides emergency stroke care. A stroke team should be ready to assess the patient in the emergency department once the patient arrives. The use of standardized stroke care order sets is recommended to improve management.[20][21][20]

In hospitals without expertise in imaging interpretation, teleradiology systems implemented within a telestroke network are useful in supporting a rapid interpretation of the images in a timely manner for alteplase administration decision-making. Administration of alteplase guided by telestroke consultation may be as safe and beneficial as that of stroke centers. Telestroke systems are also useful for triaging patients who may be eligible for interfacility transfer for consideration of mechanical thrombectomy.[21]

Continuous quality improvement processes implemented by each major element of the stroke system of care can be useful in improving patient care and outcome.[20][21]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kubis N,Guichard JP,Woimant F, Isolated anterior cerebral artery infarcts: A series of 16 patients. Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 1999 May-Jun; [PubMed PMID: 10207214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChandra A,Li WA,Stone CR,Geng X,Ding Y, The cerebral circulation and cerebrovascular disease I: Anatomy. Brain circulation. 2017 Apr-Jun; [PubMed PMID: 30276305]

Kumral E,Bayulkem G,Evyapan D,Yunten N, Spectrum of anterior cerebral artery territory infarction: clinical and MRI findings. European journal of neurology. 2002 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 12453077]

Toyoda K, Anterior cerebral artery and Heubner's artery territory infarction. Frontiers of neurology and neuroscience. 2012; [PubMed PMID: 22377877]

Krishnan M,Kumar S,Ali S,Iyer RS, Sudden bilateral anterior cerebral infarction: unusual stroke associated with unusual vascular anomalies. Postgraduate medical journal. 2013 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 22955997]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArboix A,García-Eroles L,Sellarés N,Raga A,Oliveres M,Massons J, Infarction in the territory of the anterior cerebral artery: clinical study of 51 patients. BMC neurology. 2009 Jul 9; [PubMed PMID: 19589132]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKang SY,Kim JS, Anterior cerebral artery infarction: stroke mechanism and clinical-imaging study in 100 patients. Neurology. 2008 Jun 10; [PubMed PMID: 18541871]

Hensler J,Jensen-Kondering U,Ulmer S,Jansen O, Spontaneous dissections of the anterior cerebral artery: a meta-analysis of the literature and three recent cases. Neuroradiology. 2016 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 27516097]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohindra S,Kovai P,Chhabra R, Fatal Bilateral ACA Territory Infarcts after Pituitary Apoplexy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Skull base : official journal of North American Skull Base Society ... [et al.]. 2010 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 21311623]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKurre W,Vorlaender K,Aguilar-Pérez M,Schmid E,Bäzner H,Henkes H, Frequency and relevance of anterior cerebral artery embolism caused by mechanical thrombectomy of middle cerebral artery occlusion. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2013 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 23471019]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNagaratnam N,Davies D,Chen E, Clinical effects of anterior cerebral artery infarction. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 1998 Nov-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 17895117]

Bogousslavsky J,Martin R,Moulin T, Homolateral ataxia and crural paresis: a syndrome of anterior cerebral artery territory infarction. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1992 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 1479393]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHonig A,Eliahou R,Auriel E, Confined anterior cerebral artery infarction manifesting as isolated unilateral axial weakness. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2017 Feb 15; [PubMed PMID: 28131184]

Kobayashi S,Maki T,Kunimoto M, Clinical symptoms of bilateral anterior cerebral artery territory infarction. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2011 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 21159512]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEdlow JA,Selim MH, Atypical presentations of acute cerebrovascular syndromes. The Lancet. Neurology. 2011 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 21601162]

Nishida Y,Irioka T,Sekiguchi T,Mizusawa H, Pure sensory infarct in the territories of anterior cerebral artery. Neurology. 2010 Jul 20; [PubMed PMID: 20644157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBejot Y,Caillier M,Osseby GV,Didi R,Ben Salem D,Moreau T,Giroud M, Involuntary masturbation and hemiballismus after bilateral anterior cerebral artery infarction. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2008 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 17961914]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBirenbaum D,Bancroft LW,Felsberg GJ, Imaging in acute stroke. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2011 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 21694755]

Jensen UR,Weiss M,Zimmermann P,Jansen O,Riedel C, The hyperdense anterior cerebral artery sign (HACAS) as a computed tomography marker for acute ischemia in the anterior cerebral artery territory. Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2010; [PubMed PMID: 19907164]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJauch EC,Saver JL,Adams HP Jr,Bruno A,Connors JJ,Demaerschalk BM,Khatri P,McMullan PW Jr,Qureshi AI,Rosenfield K,Scott PA,Summers DR,Wang DZ,Wintermark M,Yonas H, Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013 Mar [PubMed PMID: 23370205]

Powers WJ,Rabinstein AA,Ackerson T,Adeoye OM,Bambakidis NC,Becker K,Biller J,Brown M,Demaerschalk BM,Hoh B,Jauch EC,Kidwell CS,Leslie-Mazwi TM,Ovbiagele B,Scott PA,Sheth KN,Southerland AM,Summers DV,Tirschwell DL, 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018 Mar [PubMed PMID: 29367334]

Musuka TD,Wilton SB,Traboulsi M,Hill MD, Diagnosis and management of acute ischemic stroke: speed is critical. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2015 Sep 8; [PubMed PMID: 26243819]

Uno J,Kameda K,Otsuji R,Ren N,Nagaoka S,Kazushi M,Ikai Y,Gi H, Mechanical Thrombectomy for Acute Anterior Cerebral Artery Occlusion. World neurosurgery. 2018 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 30189299]

Roessler K,Krawagna M,Dörfler A,Buchfelder M,Ganslandt O, Essentials in intraoperative indocyanine green videoangiography assessment for intracranial aneurysm surgery: conclusions from 295 consecutively clipped aneurysms and review of the literature. Neurosurgical focus. 2014 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 24484260]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAllen CM, Differential diagnosis of acute stroke: a review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1984 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 6387114]

Deborah G,Ong E,Nighoghossian N, Akinetic mutism reversibility after L-dopa therapy in unilateral left anterior cerebral artery infarction. Neurocase. 2017 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 28447507]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence