Introduction

Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is the mildest variant of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. In 1940, Lichtenstein and Jaffe first introduced the term EG. Lichtenstein in 1953 included eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Schuller-Christian disease, and Letterer-Siwe disease under the disorder histiocytosis X referring to the proliferation of histiocytes (Langerhans cells) due to an unknown etiology. They are now known as Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). EG is a benign tumor-like disorder characterized by abnormal proliferation of antigen-presenting cells of dendritic origin known as Langerhans cells. These Langerhans cells originate from meloid dendritic cells rather than skin. EG is the most common form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.[1]

The disease mostly affects the axial skeleton, namely skull, jaw bone, spine, pelvis, ribs, and long bones. Lesions in the long bones are primarily located in the diaphysis. It frequently involves the soft tissues adjacent to the bone. The site of bone involvement is different in children and adults. In children most commonly involved bone is the skull (frontal bone), in contrast to adults, where the jaw is more frequently involved. The thoracic spine is most often involved in children as opposed to the cervical spine in adults.[2][3] Other less commonly affected sites include the skin, pituitary gland, lung, brain, liver, spleen, and the gastrointestinal tract.[4][5][6][7][8] EG accounts for less than 1% of all bone tumors. The presentation of EG is either solitary, which rarely requires treatment or multisystem, which requires aggressive therapy.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Classification[9]

- Eosinophilic Granuloma:

- Single bone lesion (Monostotic): More common and seen in nearly 90% of patients.

- Multiple bone lesions (Polyostotic): Less common and seen in nearly 10% of patients.

- Hand-Schuller-Christian Disease: Characterized by a classic triad of exophthalmos, diabetes insipidus, and osteolytic skull lesions.[10]

- Letterer-Siwe Disease: Characterized by lymphadenopathy, skin rash, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia.[11]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There is an ongoing debate on whether eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is a reactive or neoplastic process. The abnormal proliferation of Langerhans cells characterizes EG. Langerhans cells are derived from a mononuclear cell and dendritic line precursors. They are generally found in the bone marrow with the ability to migrate into tissues and act as antigen-presenting cells to T lymphocytes. The proliferation of Langerhans cells may be induced by a viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus, Human Herpes virus-6), bacteria, and immune dysfunction leading to an increase in cytokines such as interleukin-1 and interleukin-10.[12] EG of the lung has a strong association with cigarette smoking.[13] Langerhans cell histiocytosis is now considered as an inflammatory myeloid neoplasm in the revised 2016 Histiocyte Society classification.[14]

The accumulation of Langerhans cells in the lungs occurs in response to exposure to cigarette smoke. Supporting this hypothesis is the finding that the initial histologic and radiographic findings are peribronchial. Antigenic stimulation from one or more components of cigarette smoke is likely responsible for the disease.

Epidemiology

Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is a rare disorder with an incidence of 4 to 5 cases per million per year in children's less than 15 years, while the incidence is 1 to 2 cases per million per year in adults.[15] The incidence is higher in the white population of northern European descent and Hispanics than in the black race. It affects children, adolescents, and young adults, with the most commonly affected age group being 5 to 10 years. The mean age group for the patients with single bone lesions is 5.5 years, and with multiple bone lesions are 4.5 years. Males are slightly more affected than females 1.2:1. There are few reported cases of EG in the same family members. The pattern of inheritance is not well recognized.

Eosinophilic granuloma in the lungs is a rare disorder, and true prevalence is not known. Less than 5% of patients who had lung biopsy for interstitial lung disease were diagnosed with EG of the lung.[16] A Japanese study estimated the prevalence of lung EG at 0.27 males and 0.07 females per 100,000 population-based on hospital discharge diagnosis over a year.[17]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is not clearly understood. Langerhans cells are differentiated cells of the dendritic cell system and are closely related to the monocyte-macrophage line. These antigen-presenting cells are normally found in the skin, reticuloendothelial system, heart, pleura, and lungs. They may be identified by immunohistochemical staining or by the presence of Birbeck granules via electron microscope. It is believed that it can be either due to a reactive or neoplastic process. There have been reports suggesting somatic mutations (gain of function mutation) in the BRAF V600E gene in 50% of cases.[18] Also, MAP2K1 mutations are found in 21% of the cases.[19] Langerhans cell histiocytosis had been associated with Ras-ERK pathway mutations.[19]

Studies have since reported that 100% of the cases show ERK phosphorylation.[14] The protein produced by the BRAF gene is a part of the signaling pathway known as the RAS/MAPK pathway that regulates proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis of the cells. This mutation leads to an overactive protein that constantly sends the signal to the nucleus for growth and proliferation, which subsequently leads to the formation of EG due to abnormal proliferation of the Langerhans cells. This can either involve the skeletal system or other organ systems. Depending on the maturation stage of the dendritic cell when the mutation occurs, it is the clinical presentation—the more mature the cell, the less systemic involvement. Langerhans cells infiltrating multiple organ systems are found to have the BRAF gene mutation, which has shown a good response to chemotherapy.[14][18][20]

Histopathology

Histopathological examination is required for the diagnosis of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis (EG) to differentiate from other conditions like infections, malignancy, and benign tumors of the bone as their clinical presentation and laboratory findings are somewhat similar.

Histopathological Finding:

- Shows Langerhans cells, which are mononuclear histiocyte-like cells with prominent nuclear grooves (coffee-bean) and admixed eosinophils (gives the pink appearance of cytoplasm).

- Scattered multinucleated Touton like giant cells, inflammatory cells, and areas of necrosis.

- Staining positive for CD1 antigen, S-100 protein, CD207 (Langerin), cyclin D1, PNA (peanut agglutinin), BRAF VE1 (50% of cases).

- Lack of nuclear atypia and atypical mitoses (differentiates from malignant conditions).[20]

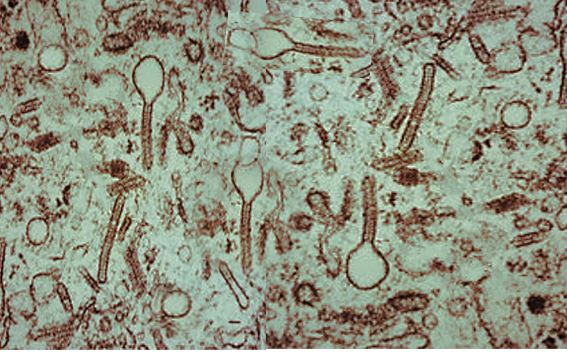

Electron Microscopy:

- Shows Birbeck granules inside Langerhans cells. Birbeck granules are "tennis racquet shaped" cytoplasmic inclusions with zipper-like appearance.

History and Physical

Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is a multi-system disease with a diverse presentation. It can involve a single bone or multiple bones, and the clinical presentation varies with the involved bone and surrounding structures. Other than bones, less commonly involved organs include skin, pituitary gland, liver, spleen, and lungs. The clinical features, according to involved structures, are as follows:

- Pain and swelling in the region of involved bone is the most common presenting symptom

- Pathological fracture of the involved bone

- Vertebral involvement may present with back pain, stiffness, and change in posture (kyphotic posture). More extensive lesions can cause neurological deficits.[21]

- Temporal bone involvement may present with ear canal mass, postauricular swelling, ear discharge, and hearing loss. Children presenting with symptoms of otitis media not responding to appropriate antibiotics should raise suspicion for EG.

- Periorbital lesions may present with periorbital edema, redness, fever, and proptosis (mimicking cellulitis), which shows no improvement with antibiotics.[22]

- Jaw involvement may present with jaw mass, pain, and loose teeth.

- Lesions involving the skull may present with headache, increased thirst, and increase urination (diabetes insipidus).[23]

- Lesions involving lung may be asymptomatic or present with non-productive cough, weight loss, dyspnea, chest pain, fatigue, and spontaneous pneumothorax.

Physical Findings:

- Tenderness to palpation of the affected region, normal/restricted range of motion of the spine in case of lesions involving vertebral bones. The mass may be firm and immobile.

- Limping can be seen in lesions involving the pelvis and lower extremities long bones.

- Conductive or sensorineural hearing loss.

- Neurological examinations may show neurological deficits in case of extensive spine involvement.

- Abdominal examinations may show hepatosplenomegaly, and lymph node may be enlarged in case of multi-system involvement.

- Chest auscultation may be abnormal in the pulmonary EG.

Evaluation

The evaluation of eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is multicentric that includes laboratory tests, radiographic tests, and biopsy for histopathological findings to reach an accurate diagnosis.

Laboratory Tests

- Complete blood count with differential is often normal, or there might be mild leukocytosis in patients with EG. It should be done to rule out other conditions mimicking EG like osteomyelitis and malignancy. Unexplained cytopenias should be further evaluated with bone marrow biopsy.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be elevated in patients with EG, but it is an inconsistent finding.[24]

Radiographic Tests

- X-ray of the involved bone may show a punched-out lytic bone lesion with or without periosteal reaction. The bony cortex may be thinned, expanded, or destroyed. X-ray of the skull shows a classic punched-out lytic lesion. Both outer and inner table involvement gives the beveled-edge appearance. X-ray of the spine may show lytic lesions, vertebral collapse involving the pedicles and posterior vertebral elements (vertebra plana or coin on edge appearance), and increased kyphosis. The differential diagnosis for these findings includes multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, osteomyelitis, tuberculosis, leukemia, and lymphoma.

- A complete skeletal survey is done to look for similar lesions on other sites along with a chest x-ray to look for pulmonary involvement.

- Chest x-ray in patients with pulmonary involvement characteristically reveals bilateral, symmetric, ill-defined nodules and reticulonodular infiltrates. As the disease progresses, cystic lesions appear. An upper lobe predominance with sparing of costophrenic angles is typically observed.

- Computed tomographic (CT) scan, positron emission tomography scan, and magnetic resonance imaging should be done in cases involving the skull, mandible, and spine. Posterior elements of vertebral bodies are difficult to visualize by x-ray due to complex anatomy, which requires a spine CT scan. These scans may show punched-out lesions along with any soft tissue involvement adjacent to the bony structure.

- Radionuclide bone scan shows increased uptake in the region of the lesion.

Biopsy

- Fine-needle aspiration or CT-guided biopsy of the suspected bone lesion and staining for CD1a and CD207 is done to confirm the diagnosis of EG.[20]

- BRAF V600E mutation testing is done in patients with central nervous system lesions, diagnostic dilemmas, and those requiring targeted therapy.

- Electron microscopy can be done to see the Birbeck granules.

Ancillary Tests

- Pulmonary function test for any lung involvement

- Bronchoalveolar lavage is diagnostic in pulmonary EG. A 5% increase in Langerhans cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is pathognomonic.

- Neurological and visual testing for lesions involving skull and orbit

- Auditory testing for lesions involving the temporal bone

Treatment / Management

The treatment can be divided into two groups:

Non-operative

- Observation: Solitary lesions are generally self-limited with spontaneous regression. Thus, skeletally immature patients and asymptomatic patients with solitary lesions are observed for spontaneous regression. They are followed up at regular intervals.

- Immobilization: Patients with a spinal lesion producing pain with no or minimal neurological deficits should be immobilized. Bracing can be done in patients presenting with kyphosis.

- Low Dose Irradiation: The dose range is 6 to 12 Gy delivered at 2 Gy per fraction. It is given for symptomatic lesions that are persistent or relapse after conservative treatment or lesions involving vital structures—also given in patients with mild neurological deficits.

- Methylprednisolone Injection: Intralesional methylprednisolone injection (40mg to 160 mg) is given for symptomatic lesions of the spine and extremities. Corticosteroids are also offered in pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma (EG) when there are significant pulmonary and constitutional symptoms.

- Chemotherapy: High-risk patients like skeletal mature, polyostotic EG, CNS-risk bones involvement (sphenoid, ethmoid, orbital, or temporal), and multisystem involvement should be treated with systemic chemotherapy (vinblastine and prednisone or cytarabine for 12 months).[14]

- Smoking cessation helps in stabilizing the pulmonary EG, stop its progression, and prevent bronchogenic carcinoma. (B3)

Operative

- Curettage and Bone Grafting: Solitary skull lesions are treated with curettage after biopsy, followed by bone grafting. Lesions that are at risk for impending fracture are also treated with curettage followed by bone grafting.

- Surgical Fixation: Surgical fixation is done for patients with severe pain, restricted range of motion, progressive neurological deficits, and spinal instability.[25]

- Chest Intubation and Pleurodesis: Pneumothorax in pulmonary EG is managed with chest intubation followed by pleurodesis. If recurrent, then pleurectomy can be done.

- Lung Transplantation: In advanced disease, lung transplantation can be helpful.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eosinophilic granuloma (EG) involving the spine includes

- Neurofibroma

- Schwannoma

- Leukemia

- Lymphomas

- Multiple myeloma

- Osteomyelitis

- Tuberculosis

- Plasmacytoma

- Metastasis

They have similar radiological findings; however, minimal laboratory findings and lack of constitutional symptoms favor EG. The biopsy of the lesion confirms the diagnosis.

For lesions involving the skull bone, the differential diagnosis includes

- Otitis media

- Mastoiditis

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Periorbital cellulitis

For lesions involving the long bones of the extremities, the differential diagnosis includes

- Ewing's sarcoma

- Osteochondroma

- Osteoblastoma

- Osteosarcoma

- Paget's disease

In the case of pulmonary EG following differentials to be kept in mind

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- Pulmonary histiocytic sarcoma

- Cystic fibrosis

- Emphysema

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Sarcoidosis

Biopsy and histopathological analysis, staining for CD1a, and electron microscopic finding help in differentiating EG with these conditions.[26]

Prognosis

Patients with solitary bone lesions may regress spontaneously and have a good prognosis. High-risk patients like multisystem involvement, skeletally mature patients, more than one bone involvement, and skull-base bone involvement (sphenoid, ethmoid, orbital, and temporal bones) have a high risk for recurrence, complications, and subsequent worse prognosis. Operative treatment offers more prompt pain relief when compared to non-operative treatment.[27] Over 10% of patients die of this disease, including a few cases with reactivations and long term morbidity.[15]

The prognosis for pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma (EG) varies and is related to smoking cessation. Those who continue to smoke experience disease progression, but those who quit disease stabilizes or regresses. Extreme age, large cysts, and honeycombing radiological, multiorgan involvement, and prolonged corticosteroid therapy have a worse prognosis.

Complications

The complications associated with eosinophilic granuloma (EG) are as follows:

- Musculoskeletal disability or restricted activity

- Growth disturbance

- Pathological fractures

- Hearing and vision impairment

- Neuropsychiatric problems like depression and anxiety

- Post-radiation sarcomas and myelitis

- Methylprednisolone injection associated osteomyelitis

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

- Increased risk of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloproliferative disorders and bronchogenic carcinoma

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension and cor pulmonale

Consultations

Patients with eosinophilic granuloma (EG) should get multiple consultations according to the involved organs and presenting complaints. These are:

- Orthopedist

- Spine neurosurgeon or orthopedist

- Radiologist

- Ophthalmologist

- Pulmonologist

- Otolaryngologist

- Neurologist

- Hematologist-oncologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

- Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is a benign disorder of the bone.

- An asymptomatic solitary lesion may resolve spontaneously and require no treatment, however, there is a risk of developing additional bone lesions within 6 months to 2 years. Thus, regular follow up with a complete skeletal survey is required.

- Children with multiple bone lesions should be evaluated for systemic involvement.[23]

- There is an increased incidence of thyroid disease in the family members of a patient with EG.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is the mild form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, most commonly affecting the axial skeleton. It is more common in children and adolescents. The presenting complaints, laboratory findings, and radiographic features might be similar to some other conditions like infections, malignancy, and metastasis. Thus, histopathological features along with staining with CD1a, S-100 protein, and electron microscopic features are required to differentiate from other conditions mimicking EG.

EG can present as either single bone involvement, multiple bone involvement, or multiple system involvement. Thus, a multicentric approach is required while evaluating a suspected case of EG. Solitary lesions generally require no treatment and have a good prognosis. While the orthopedic surgeon is almost always involved in the care of patients with EG, it is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include an ophthalmologist, pulmonologist, hematologist-oncologist, otolaryngologist, neurosurgeon, and neurologist. The nurses are also vital members of the interprofessional group as they will assist with the education of the patient and family. In the postoperative period for pain and wound infection, the pharmacist will ensure that the patient is on the right analgesics and appropriate antibiotics. The radiologist also plays a vital role in determining the cause. Without providing a proper history, the radiologist may not be sure what to look for or what additional radiologic exams may be needed.

Media

References

Bang WS, Kim KT, Cho DC, Sung JK. Primary eosinophilic granuloma of adult cervical spine presenting as a radiculomyelopathy. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2013 Jul:54(1):54-7. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2013.54.1.54. Epub 2013 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 24044083]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIslinger RB, Kuklo TR, Owens BD, Horan PJ, Choma TJ, Murphey MD, Temple HT. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis in patients older than 21 years. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2000 Oct:(379):231-5 [PubMed PMID: 11039811]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCochrane LA, Prince M, Clarke K. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis in the paediatric population: presentation and treatment of head and neck manifestations. The Journal of otolaryngology. 2003 Feb:32(1):33-7 [PubMed PMID: 12779259]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSherwani RK, Akhtar K, Qadri S, Ray PS. Eosinophilic granuloma of the mandible: a diagnostic dilemma. BMJ case reports. 2014 Apr 3:2014():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200274. Epub 2014 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 24700031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBajracharya B , Poudel P , Bajracharya D , Bhattacharyya S , Shakya P . Eosinophilic Granuloma of Mandible: A Diagnostic Challenge. Kathmandu University medical journal (KUMJ). 2018 Apr-Jun:16(62):201-203 [PubMed PMID: 30636766]

Prasad GL, Divya S. Eosinophilic Granuloma of the Cervical Spine in Adults: A Review. World neurosurgery. 2019 May:125():301-311. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.230. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30771538]

Öğrenci A, Batçık OE, Ekşi MŞ, Koban O. Pandora's box: eosinophilic granuloma at the cerebellopontine angle-should we open it? Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2016 Aug:32(8):1513-6. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2982-1. Epub 2015 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 26661575]

Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, Schäfer E, Nanduri V, Jubran R, Egeler RM, Janka G, Micic D, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Van Gool S, Visser J, Weitzman S, Donadieu J, Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2013 Feb:60(2):175-84. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24367. Epub 2012 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 23109216]

Huang WD, Yang XH, Wu ZP, Huang Q, Xiao JR, Yang MS, Zhou ZH, Yan WJ, Song DW, Liu TL, Jia NY. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of spine: a comparative study of clinical, imaging features, and diagnosis in children, adolescents, and adults. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013 Sep:13(9):1108-17. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.03.013. Epub 2013 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 23602327]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLalitha Ch, Manjula M, Srikant K, Goyal S, Tanveer S. Hand schuller christian disease: a rare case report with oral manifestation. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2015 Jan:9(1):ZD28-30. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/10985.5481. Epub 2015 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 25738095]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Mohannadi M, Yakoub R, Soofi ME, Elsabah HM, Thandassery RB. Gastrointestinal: Letterer Siwe disease: An uncommon gastrointestinal presentation. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2016 Jun:31(6):1070. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13293. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26757250]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChadha M, Agarwal A, Agarwal N, Singh MK. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the radius. An unusual differential diagnosis. Acta orthopaedica Belgica. 2007 Jun:73(3):413-7 [PubMed PMID: 17715738]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMa J, Laird JH, Chau KW, Chelius MR, Lok BH, Yahalom J. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults is associated with a high prevalence of hematologic and solid malignancies. Cancer medicine. 2019 Jan:8(1):58-66. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1844. Epub 2018 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 30597769]

Kobayashi M, Tojo A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: Advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Cancer science. 2018 Dec:109(12):3707-3713. doi: 10.1111/cas.13817. Epub 2018 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 30281871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015 Jul 2:126(1):26-35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-569301. Epub 2015 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 25827831]

Gaensler EA, Carrington CB. Open biopsy for chronic diffuse infiltrative lung disease: clinical, roentgenographic, and physiological correlations in 502 patients. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1980 Nov:30(5):411-26 [PubMed PMID: 7436611]

Watanabe R, Tatsumi K, Hashimoto S, Tamakoshi A, Kuriyama T, Respiratory Failure Research Group of Japan. Clinico-epidemiological features of pulmonary histiocytosis X. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2001 Oct:40(10):998-1003 [PubMed PMID: 11688843]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBadalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, Calicchio ML, Kuo FC, Ligon AH, Stevenson KE, Kehoe SM, Garraway LA, Hahn WC, Meyerson M, Fleming MD, Rollins BJ. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010 Sep 16:116(11):1919-23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083. Epub 2010 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 20519626]

Tran G, Huynh TN, Paller AS. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A neoplastic disorder driven by Ras-ERK pathway mutations. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Mar:78(3):579-590.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.022. Epub 2017 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 29107340]

Kumar N, Sayed S, Vinayak S. Diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis on fine needle aspiration cytology: a case report and review of the cytology literature. Pathology research international. 2011 Jan 20:2011():439518. doi: 10.4061/2011/439518. Epub 2011 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 21331166]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRai S, Sridevi HB, Pai RR, Sanyal P. A Case of Multifocal Eosinophilic Granuloma Involving Spine and Pelvis in a Young Adult: A Radiopathological Correlation. Indian journal of medical and paediatric oncology : official journal of Indian Society of Medical & Paediatric Oncology. 2017 Oct-Dec:38(4):555-558. doi: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_130_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29333031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAli-Ridha A, Brownstein S, O'Connor M, Gilberg S, Tang T. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an 18-month-old child presenting as periorbital cellulitis. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2018 Jan-Mar:32(1):52-55. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2018.02.006. Epub 2018 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 29755272]

Kaul R, Gupta N, Gupta S, Gupta M. Eosinophilic granuloma of skull bone. Journal of cytology. 2009 Oct:26(4):156-7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.62188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21938183]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAngelini A, Mavrogenis AF, Rimondi E, Rossi G, Ruggieri P. Current concepts for the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic granuloma of bone. Journal of orthopaedics and traumatology : official journal of the Italian Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2017 Jun:18(2):83-90. doi: 10.1007/s10195-016-0434-7. Epub 2016 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 27770337]

Nezafati S, Yazdani J, Shahi S, Mehryari M, Hajmohammadi E. Outcome of Surgery as Sole Treatment of Eosinophilic Granuloma of Jaws. Journal of dentistry (Shiraz, Iran). 2019 Sep:20(3):210-214. doi: 10.30476/DENTJODS.2019.44903. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31579697]

Kamal AF, Luthfi APWY. Diagnosis and treatment of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis with bone lesion in pediatric patient: A case report. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2019 Sep:45():102-109. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2019.07.030. Epub 2019 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 31452877]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhou Z, Zhang H, Guo C, Yu H, Wang L, Guo Q. Management of eosinophilic granuloma in pediatric patients: surgical intervention and surgery combined with postoperative radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2017 Apr:33(4):583-593. doi: 10.1007/s00381-017-3363-8. Epub 2017 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 28247113]