Introduction

Historically, our knowledge of peripheral nerves and peripheral nerve injuries (PNIs) came mainly from experiences on the battlefield.[1] Sir Herbert Seddon published his PNI classification system while caring for the injured during the second world war (1942).[2] Nevertheless, in modern times, it is not uncommon to encounter PNI in non-combat-related trauma cases. These injuries can be life-changing and are often associated with significant morbidity, potentially leading to significant disabilities. Given that they mostly present in young adults of working age, these disabilities carry lifelong implications for the patients.[3]

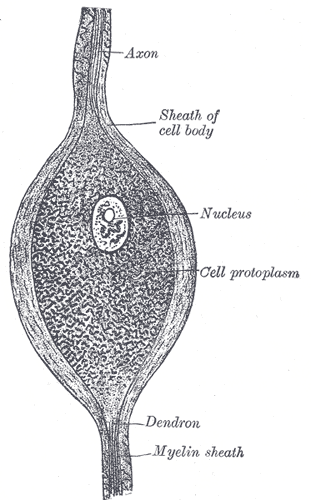

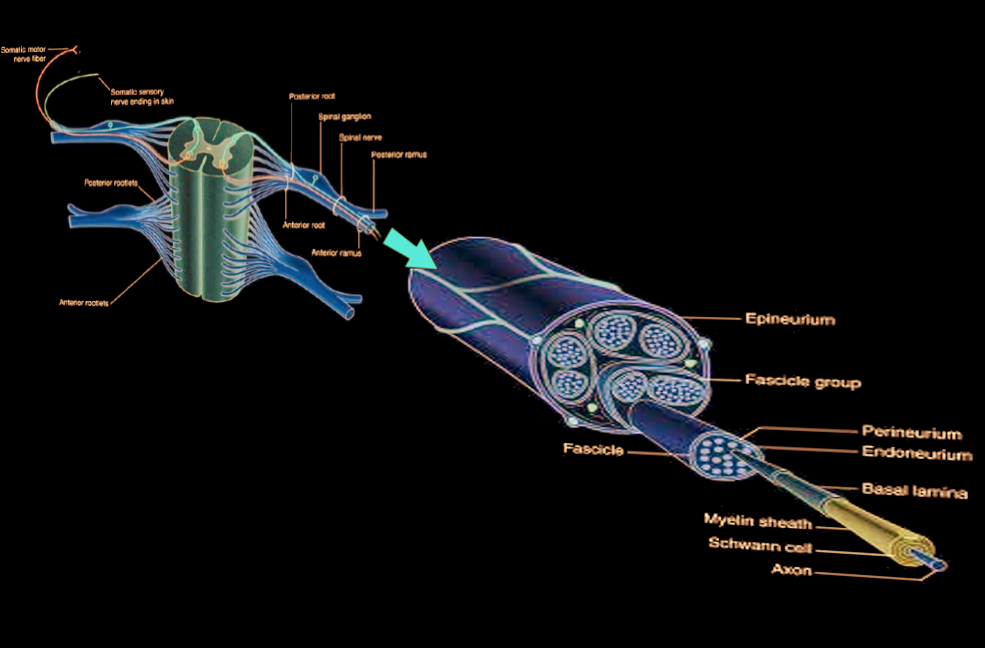

Peripheral nerve trunks are composed of three separate layers surrounding nerve fibers. The innermost collagenous endoneurium layer envelops the axonal fibers (myelinated or unmyelinated) to provide mechanical and metabolic support. Together they make up the nerve fascicles, each of which is surrounded by a flattened cellular layer called the perineurium. The outer most collagenous layer, called the epineurium, surrounds the fascicles. Knowledge of this anatomy is essential for comprehending the classifications, clinical findings, and prognosis of PNIs and, thus, the best possible management for each patient.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most common cause of PNIs (46%) is motor vehicle crashes (MVC) followed by motorcycle crashes (9.9%).[5] On the other hand, the most common causes of PNIs in combat are shrapnel and explosions.[6] Other common causes of PNIs, in general, include vehicle vs. pedestrian injuries, gunshot wounds, falls, industrial accidents, stab wounds, recreational MVC (e.g., snowmobiles), and assaults.[5] Additionally, iatrogenic injuries caused by medical or surgical procedures constitute 17.4% of surgically treated PNIs according to one study.[7]

There are multiple possible mechanisms of acute PNIs. These include[6][8]:

- Stretch-related injuries, the most common type, happen when the stretching forces overcome the nerve’s elasticity. These injuries can be either isolated nerve injuries or associated with fractures of the extremities. They usually do not affect the continuity of nerve elements but may occasionally lead to complete loss of continuity, such as brachial plexus avulsion injuries.

- Laceration injuries caused by sharp objects (e.g., knives or blades) are the second most common type. They typically produce a partial loss of continuity, but complete loss of continuity is also possible.

- The third common type of PNI is compression injuries. Despite complete nerve continuity preservation, they can result in total loss of both motor and sensory nerve functions. Both ischemia and mechanical deformation, from direct compression effect, are thought to contribute to the injuries. Mechanical deformation is the main culprit in the more severe cases where neurological deficits last longer and may not necessarily show complete recovery. On the other hand, short term ischemia lasting less than 8 hours does not appear to cause any irreversible deficits and is not associated with any significant histological changes.

- Other less common mechanisms include thermal injury or ischemia due to a vascular injury.

- A combination of injury mechanisms may present.

It merits mentioning that some of the nerves are more vulnerable to injury due to their anatomical course (superficial and close to a bony structure and/or joint, so they are amenable to compression or stretching). For example, radial nerve (passes along the spiral groove of humerus shaft) injury due to improper prolonged sitting position on a chair or what is so-called “Saturday night palsy.”[9] This type of injury presents clinically as wrist and finger weakness. The ulnar nerve injury and common peroneal nerve in lower extremities are other examples. Post-operative ulnar nerve injury is a frequent problem, and in one series, it constituted up to 17 % of cases. It results from a patient’s malposition that causes ulnar nerve stretch or compression at the elbow level.[10] In lithotomy position, the common peroneal nerve is at risk of compression between the fibular head and the leg holder, particularly in thin patients and during lengthy procedures.[11]

Moreover, acute nerve injury can be associated with bone fractures. The injury can be primary (at the time of fracture) or secondary, which can be iatrogenic or from scar or callus formation. Radial nerve injury is associated with humeral shaft fracture and considered the most common peripheral nerve injury related to bone fracture (more than 10% of the cases).[12] Furthermore, PNI can occur due to joints dislocation, as well. Axillary nerve injury, for instance, can be a sequela of glenohumeral joint dislocation due to the proximity of the nerve course to the joint capsule.[13] Additionally, some nerves can suffer an injury during certain surgeries due to compression, stretch, or ischemia. For example, brachial plexus injury during placement of sternal retractors for sternotomy. Another example is the femoral nerve injury due to self-retaining retractor during abdominal surgery.[14]

Epidemiology

PNIs occur in approximately 3% of trauma patients.[15] This percentage increases to around 5% of injuries with the inclusion of injuries to nerve roots, plexuses, digital nerve, or minor nerve injuries. 59% of the patients are 18 to 35 years old, with an average patient age of 34.6 years. Males have a significantly higher incidence of PNIs than females with a male to female ratio of approximately 5 to 1.[1][5] About 60.5% of PNIs occur in the upper limbs, while 6.2% of cases involve nerve injuries in both upper and lower limbs. The radial nerve ranks as the most commonly injured. In the lower limbs, However, peroneal nerve is the most commonly injured nerve.[5]

Pathophysiology

Few pathological changes occur in pure conduction block injuries (first grade, see Sunderland classification below). All other grades of nerve injuries undergo an anterograde degeneration process distal to the injury location, known as Wallerian degeneration. This process starts hours after the injury with axonal and myelin fragmentation. The neurotubules and neurofilaments lose their organization, and the shape of the axons becomes irregular due to varicose swelling. Axonal continuity gets lost at 48 to 96 hours from injury, and impulses conduction halts. The myelin disintegration is slightly slower than axonal degradation.[8]

Schwan cells b activated within 24 hours post-injury. Along with migrated macrophages, they phagocyte the axonal and myelin debris to clear the injury site in a period that can range from a week to months. The whole degenerative process is 5 to 8 weeks long at the end of which the endoneurial tubes would have shrunk in diameter despite swelling for two weeks post-injury. Schwan cell bands (bands of Bungner) remain inside the endoneurial tubes to guide axonal reinnervation.[8]

In grade III injuries, a more significant local inflammatory reaction is detectable along with the retraction of the cut nerve fibers due to the elasticity of endoneurium. The resultant proliferation of fibroblasts creates a thick fibrous scar leading to a fusiform swelling in the injury site. This result is worse in fourth and fifth-grade injuries where, additionally, Schwann cells and axons are not limited to the fasciculi or endoneurial tubes anymore. Consequently, the proximal stump becomes a swollen bulb of Schwann cells and scar tissue impeding axonal regeneration. The proximal nerve fibers, on the other hand, undergo degradation that can range from minimal to involving the cell body. The extent of the degradation depends on the proximity of injury to the cell body as well as its severity.[8]

History and Physical

Knowing the time of injury helps determine the acuity of the injury and would impact management options. The time interval between the injury and onset of the neurological symptoms could offer clues to the nature of the injury, as a delayed onset might suggest a compressive injury while an immediate onset post-injury suggests direct PNI. The mechanism of injury and severity of the impact can help in determining the extent and degree of nerve injury. This information can be of value for making clinical decisions and assessing the potential prognosis. History taking should also be focused on the neurological deficits and/or neuropathic pain distribution to help in the localization of the nerve injury.

It is important to identify signs such as lacerations, stab wounds, bullet entry/exit wounds, abrasions, or bruises. Furthermore, a detailed neurological exam is essential. A comprehensive assessment of motor power in all the muscles supplied by pertinent nerves, as well as a precise sensory examination is needed to avoid false localization. Additionally, vascular or musculoskeletal injuries can also point to the injury of adjacent nerves. Of note, musculoskeletal injuries can potentially limit the motor neurological assessment and thus should be identified and taken into consideration in the evaluation.

In cases of brachial plexus injury, a thorough exam can guide the examiner to specific clues. The presence of ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis (Horner’s syndrome) is suggestive of a proximal injury to the lower brachial plexus or avulsion of the proximal C8 and/or T1 nerve roots. Conversely, paralysis of the hemidiaphragm, winging of the scapula, and rhomboid muscle weakness would suggest a proximal upper brachial plexus injury with possible nerve root(s) avulsion.[16]

Evaluation of pertinent muscle strength is possible by using the MRC-scale (Medical Research Council of Great Britain).[17] It ranges as follows:

- Grade 0 (G0) where no muscle contraction can be elicited

- Grade 1 (G1) when there is muscle flickering but no active movement

- Grade 2 (G2) when muscle contraction can result in active motion but not against the gravity

- Grade 3 (G3) when the muscle strength can overcome gravity, but without resistance

- Grade 4 (G4) muscle contraction can be performed against resistance but not full power

- Grade 5 (G5) is full strength (normal)

The sensory function should be assessed accurately to avoid dermatomal overlap. Therefore an autonomous and distinct zones dermatomes should be examined for different sensory modalities (fine touch sensations, pinprick, and temperature sensation) to minimize the misinterpretation. For instance, testing the dorsal aspect of the hand for radial nerve and volar surface of the pinky finger for ulnar nerve examination.

Evaluation

Electrodiagnostic studies are a vital part of the workup of peripheral nerve injuries, especially closed injuries. The use of both nerve conduction studies (NCS) or electromyography (EMG) in different stages post-injury can yield different clinically relevant information. In the first week post-injury, NCS help localize the lesion due to conduction block across the lesion despite the preservation of conduction through the distal stump. EMG can determine if the injury was complete or incomplete as preserved voluntary control of motor unit action potentials (MUAPS) in the target muscle indicates an incomplete injury. After the first week, nerve conduction studies can distinguish a conduction block due to neurapraxia from one due to axonotmesis or neurotmesis, as the distal stump would stop conducting at that point if there was an anatomical interruption. However, testing beyond the first week is traditionally done at 3 to 4 weeks when EMGs can also indicate denervation by detecting fibrillation potentials. Further testing at 3 to 4 months is carried out to help assess evidence for early innervation and guide further management decisions.[6] It is worth mentioning that some electrodiagnostic tests can be used to determine the injury site. For instance, a combination of normal sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) and absent somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) along with anesthesia in the affected dermatome, refers to a preganglionic injury.[18]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become increasingly useful in the assessment of PNIs, and this is particularly true in brachial plexus injuries where it is used to classify injuries based on their anatomical location along the plexus.[19] MRI in this situation allows good delineation of the plexus’ anatomy. It also is a noninvasive test that does not require a spinal tab, intrathecal contrast injection, or radiation exposure.[20]

Although promising, a stand-alone MRI cannot yet reliably differentiate between the different degrees of nerve injuries. It can, however, show evidence of muscle denervation as early as four days post-injury, particularly in the short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequence. This fact means it can detect muscle denervation before EMG. Furthermore, animal studies have shown that the use of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and diffusion tensor tractography (DTT) has the potential to diagnose and monitor the recovery in PNIs, but this is yet to be proven reliable for humans.[21][22]

Treatment / Management

The type and severity of the injury dictate the management approach. The injury can be an open or closed type. In open injuries, the injury would be surgically explored to test the nerve status (injury in-continuity, nerve discontinuity-sharp laceration, or nerve discontinuity-blunt injury). In sharp transecting nerve injuries, surgical exploration with end to end repair must be performed within 72 hours to avoid retraction of the proximal and distal stumps.[6] In contrast, blunt transecting injuries should undergo a delayed surgical repair (2 to 3 weeks) to allow scarring of damaged nerve ends. This process allows resection of the scarred tissue and repair of the healthy ends with or without nerve grafts. Open injuries with no evidence of transection are to be treated conservatively with serial clinical, electrodiagnostic, and radiological evaluations.[16](B3)

The approach to closed nerve injuries is mainly a conservative one, as most lesions are still in continuity. However, urgent intervention is necessary if there is compartment syndrome and threatening permanent nerve injury. A suspected neuropraxia or axonotmesis injury can have monitoring with serial electrodiagnostic and clinical evaluations for signs of recovery with no need for surgical intervention. By 3 to 4 months post-injury, if there is no evidence of reinnervation, neurotmesis should be suspected, and exploratory surgery must take place with intraoperative electrodiagnostic testing. Failure to record nerve action potential across the lesion would indicate neuroma resection and repair with or without grafting.[16][23] Surgical intervention is not necessary if there is a recorded nerve action potential distal to the site of the injury, as this indicates nerve injury in-continuity. (B2)

Several surgical techniques can be implemented in a stepwise fashion depending on the intra-operative findings. Neurolysis is scar dissection from around the injured segment. The scar is removable from the outer covering of the nerve (external neurolysis). On certain occasions, the scar can be within the nerve, and the release should take place between nerve fascicles (internal neurolysis). The surgeon usually uses intraoperative nerve stimulation to record nerve action potential (NAP) across the injury segment in this type of surgery. If NAP remains after neurolysis, this indicates that neurolysis is enough for nerve recovery.[24]

In case no NAP is recorded, or the nerve discontinuity is obvious, then nerve repair is required.[25] The principle is that the coaptation should be tension-free. Direct end-to-end repair is the preferred technique, performed after refreshing both ends of the nerve and removal of the non-functioning nerve segment. It is possible when no or minimal tension at both ends of the nerve. If the primary nerve ends approximation causes significant tension, then a graft insertion is necessary. Usually, an autograft is used and harvested from the sural nerve or medial antecubital nerve. Artificial grafts are available for specific purposes, such as small nerve repair in the fingers.[26][27] In complex conditions, such as severe brachial plexus injury, neurotization is necessary. It entails transferring a healthy nerve end to another injured nerve.[28](B2)

Several measures merit consideration during the postoperative period to achieve the best outcome from the surgical intervention. In certain circumstances, when the nerve repair occurs with the joint in flexion, immobilization may be required for three weeks to avoid sutures disruption. Additionally, a bulky dressing around the surgical area can be used as a cushion and as a reminder for the patient to minimize the movement around the joint. Early physiotherapy to restore joint mobility without disruption of the coapted nerves is mandatory. Physical therapy and occupational treatment are necessary to maintain the range of joint movement, preserve the elasticity of the affected muscles until the time of effective reinnervation, and to keep the strength and bulk of the unaffected muscles. The patient should understand that the recovery and hence, the rehabilitation program may take several months and maybe years until a meaningful and effective movement is achievable. Yet, it is usually incomplete. Tinel’s sign can be useful as an indicator of nerve regrowth. Needle EMG exam can be used to assess motor unit recruitment during the follow-up period.

Early pharmacotherapy for control of neuropathic pain is essential. Literature reports medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine, gabapentin or pregabalin), or serotonin reuptake inhibitors as appropriate choices.[6] Early referral to acute pain services might also be beneficial.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for acute PNIs includes:

- Spinal radiculopathy

- Spinal cord injury

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Stroke or brain injury

- Musculoskeletal or vascular injury

- Peripheral nerve tumors

Supplemented by a solid knowledge of central/peripheral nervous system anatomy and physiology, a good history and physical exam are crucial for ruling out other differential diagnoses. Further investigations with imaging and/or electrodiagnostic tests can help confirm the diagnosis.

Staging

There are two main clinical classifications of nerve injuries. The Seddon and Sunderland classifications.[8] Both systems categorize nerve injuries based on severity.

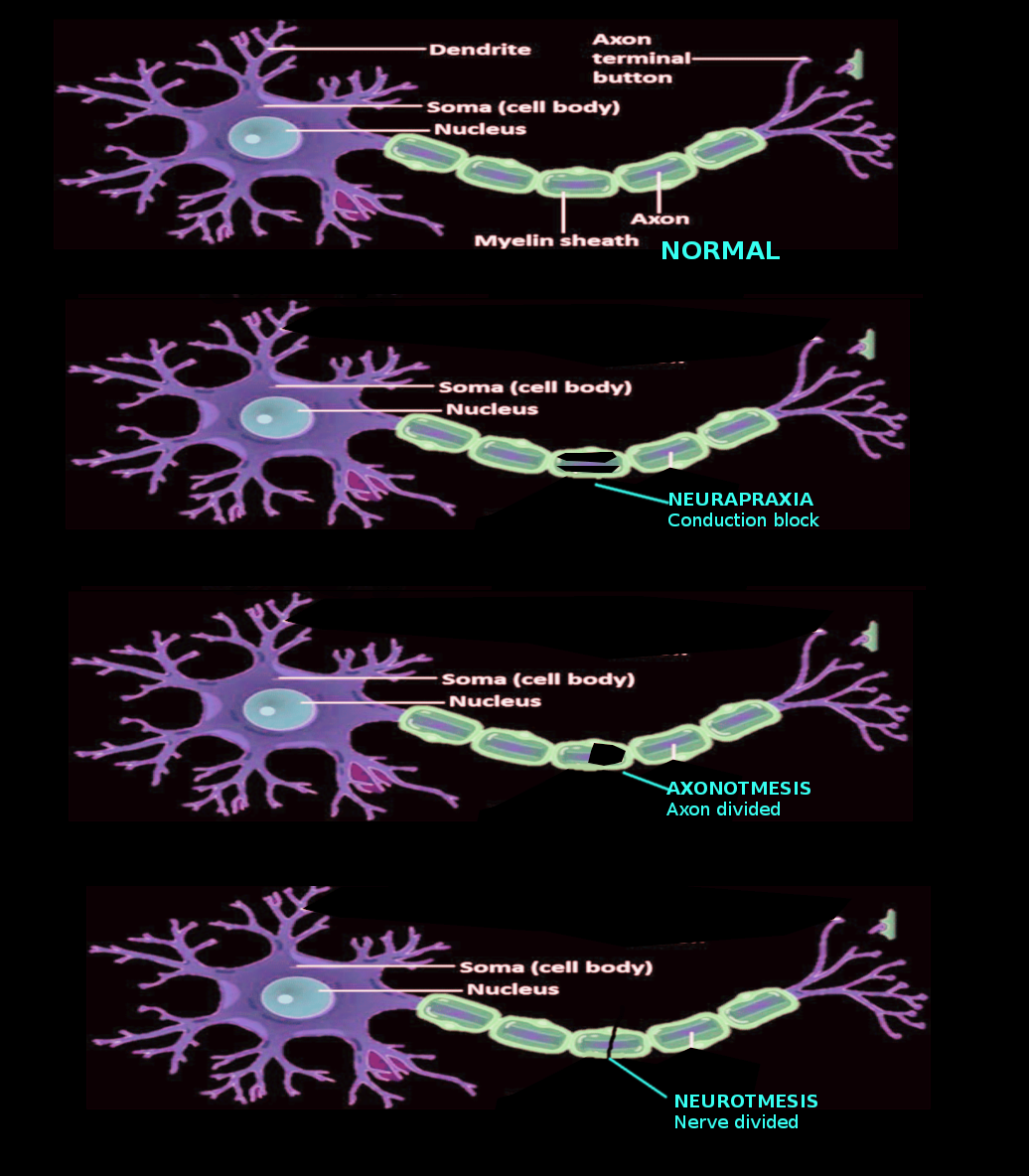

The Seddon classification describes three categories of nerve injuries. The mildest form is a neurapraxic injury and results from focal ischemia or compression. Neurapraxia affects the myelin layer of the Schwann cells resulting in demyelination. These histological changes lead to a reduction in nerve conduction or complete nerve conduction block at the level of the injury. The muscles do not show atrophy or features of denervation (spontaneous fibrillation) on EMG as the axons are intact in this type of injury. Spontaneous functional recovery is complete after weeks or months from the injury. There is no Wallerian degeneration in this category.

The second category, axonotmesis, represents axonal disruption without disruption of perineurium or epineurium. It leads to a loss of sensory and motor function. It results in Wallerian degeneration distal to the injury site. Therefore, EMG shows features of muscle denervation. The intact surrounding structure facilitates axonal regeneration. However, spontaneous functional recovery depends on several factors such as branching pattern of the affected nerve, the distance from the injury site to the neuromuscular endplate (target muscle), nerve component pure motor or sensory, or mixed. The third and most severe is neurotmesis, which results from a complete disruption of the axons and surrounding structures.[8] Because no axons to conduct the stimulation response distally, EMG shows features of muscle denervation. Neurotmesis usually results in complete functional loss. Axonal regrowth can not happen as this injury results in either a gap or fibrosis, and it requires surgical repair to remove fibrosis and bridge the gap.

On the other hand, the Sunderland classification has five grades based on the severity of the injury. The first corresponds to neuropraxia in Seddon’s classification and includes nerve conduction block due to focal myelin sheath disruption. The clinical picture entails mainly motor weakness (paralysis) and disturbance in joint sensation. Other sensory modalities and sympathetic activity are usually preserved.[29] The second grade corresponds to axonotmesis, in which axons and myelin sheath suffer disruption, yet the endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium remain. Wallerian degeneration follows the injury. Of note, the recovery follows the rule of axonal growth 1mm/day and can be poor if the target neuromuscular endplate is far from the site of the injury and needs more than 18 months for the growing nerve to reach. A grade three injury has associated endoneurium, axonal, and myelin sheath disruption. Therefore, the recovery is unexpected and can be complete or can be poor if there is intrafascicular fibrosis. Notwithstanding, on gross inspection, the nerve is not severely injured. The damage to the myelin sheath, axons, endoneurium, and perineurium with sparing of the epineurium represents a grade four injury. On gross examination, the nerve is focally enlarged and indurated. The grade five injury indicates a complete nerve dissection or complete loss of in-continuity and is equivalent to neurotmesis in Seddon’s classification.[8]

Prognosis

Predicting PNIs recovery is a complex task as recovery depends on multiple factors, including injury acuity, degree of injury, scar formation, distance to muscle, age of the patient, and whether nerve ends approximation took place if needed.[30] However, as a general role, the severity of the injury is inversely proportional to the degree of recovery.[8]

For first and second-degree injuries, the repair starts almost immediately. A good to excellent functional recovery usually occurs within weeks to months; this may be through conduction block reversal and/or axonal regeneration. Axonal regeneration has an estimated rate of 1mm/day, and the clinician can follow it by the advance of the Tinel sign.[8][30]

On the contrary, in higher degrees of injuries, Wallerian degeneration must be complete before axonal regeneration starts. Besides, the regeneration process is made more difficult by disruption of nerve architecture, which allows axons to stray out of their endoneurial tubes into the wrong endoneurial tubes or even adjacent tissues, which is especially true for complete transaction injuries (Fifth degree) in which no recovery can be expected without surgical repair and approximation.[8][30]

Complications

PNIs can result in considerable complications for the patients. These complications may be disabling and long-lasting or even irreversible. The most prominent direct complications include chronic pain, hyperesthesia, cold intolerance, and motor or sensory loss to an extremity, potentially compromising its function. However, the impact of such injuries can go beyond the physical aspect alone. Disabilities caused by PNIs can lead to loss of employment and additional financial obligations (e.g., caregivers). They can also have an adverse psychological impact and decrease the quality of life.[3][31]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Currently, there is more inclination to manage PNI in interprofessional clinics. These clinics include specialists from neurosurgery, orthopedic, neurologist, physiatry, plastic surgery, trained nurses, occupational, rehabilitation, and physiotherapy specialists, as well as neuroscience specialty nursing staff and pharmacists. These specified clinics provide the best environment for treatment and follow up of PNIs. Some of the clinics offer dedicated patient education about the situation after the injury. They teach the patients what to expect, how to handle objects, and methods to mitigate neuropathic pain that results from the injury. [Level V] Recovery after nerve injury is usually a prolonged affair, and long term follow up is necessary. Pharmacists will have involvement with medications for neuropathic pain, collaborating with nursing and clinicians to select agents, monitor dosing and adverse effects, and check for drug interactions.

A dedicated team of clinicians, nurses, and ancillary staff should monitor these patients to ensure that sensory and motor recovery is occurring. Also, in many cases, prolonged rehabilitation is necessary. Furthermore, surgeons, anesthesiologists and interventional medical personal like the interventional radiologists should be aware of the surgical approaches, patients' positions, and anatomical track of the intervention, respectively, regarding peripheral nerve courses minimizing the iatrogenic injuries of these nerves.[32][33][34] Only through this type of interprofessional team approach can optimal neurological recovery take place. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Taylor CA, Braza D, Rice JB, Dillingham T. The incidence of peripheral nerve injury in extremity trauma. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2008 May:87(5):381-5. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31815e6370. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18334923]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKaya Y, Sarikcioglu L. Sir Herbert Seddon (1903-1977) and his classification scheme for peripheral nerve injury. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2015 Feb:31(2):177-80. doi: 10.1007/s00381-014-2560-y. Epub 2014 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 25269543]

Babaei-Ghazani A, Eftekharsadat B, Samadirad B, Mamaghany V, Abdollahian S. Traumatic lower extremity and lumbosacral peripheral nerve injuries in adults: Electrodiagnostic studies and patients symptoms. Journal of forensic and legal medicine. 2017 Nov:52():89-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2017.08.010. Epub 2017 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 28886432]

King R. Microscopic anatomy: normal structure. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2013:115():7-27. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52902-2.00002-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23931772]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoble J, Munro CA, Prasad VS, Midha R. Analysis of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve injuries in a population of patients with multiple injuries. The Journal of trauma. 1998 Jul:45(1):116-22 [PubMed PMID: 9680023]

Campbell WW. Evaluation and management of peripheral nerve injury. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008 Sep:119(9):1951-65. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.018. Epub 2008 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 18482862]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKretschmer T, Antoniadis G, Braun V, Rath SA, Richter HP. Evaluation of iatrogenic lesions in 722 surgically treated cases of peripheral nerve trauma. Journal of neurosurgery. 2001 Jun:94(6):905-12 [PubMed PMID: 11409518]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBurnett MG, Zager EL. Pathophysiology of peripheral nerve injury: a brief review. Neurosurgical focus. 2004 May 15:16(5):E1 [PubMed PMID: 15174821]

Arnold WD, Krishna VR, Freimer M, Kissel JT, Elsheikh B. Prognosis of acute compressive radial neuropathy. Muscle & nerve. 2012 Jun:45(6):893-5. doi: 10.1002/mus.23305. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22581545]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWadsworth TG, Williams JR. Cubital tunnel external compression syndrome. British medical journal. 1973 Mar 17:1(5854):662-6 [PubMed PMID: 4692712]

Warner MA, Martin JT, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Chute CG. Lower-extremity motor neuropathy associated with surgery performed on patients in a lithotomy position. Anesthesiology. 1994 Jul:81(1):6-12 [PubMed PMID: 8042811]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchwab TR, Stillhard PF, Schibli S, Furrer M, Sommer C. Radial nerve palsy in humeral shaft fractures with internal fixation: analysis of management and outcome. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2018 Apr:44(2):235-243. doi: 10.1007/s00068-017-0775-9. Epub 2017 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 28280873]

Avis D, Power D. Axillary nerve injury associated with glenohumeral dislocation: A review and algorithm for management. EFORT open reviews. 2018 Mar:3(3):70-77. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170003. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29657847]

Warner MA. Perioperative neuropathies. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1998 Jun:73(6):567-74 [PubMed PMID: 9621866]

Nadi M, Ramachandran S, Islam A, Forden J, Guo GF, Midha R. Testing the effectiveness and the contribution of experimental supercharge (reversed) end-to-side nerve transfer. Journal of neurosurgery. 2018 May 18:130(3):702-711. doi: 10.3171/2017.12.JNS171570. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29775143]

Grant GA, Goodkin R, Kliot M. Evaluation and surgical management of peripheral nerve problems. Neurosurgery. 1999 Apr:44(4):825-39; discussion 839-40 [PubMed PMID: 10201308]

Dyck PJ, Boes CJ, Mulder D, Millikan C, Windebank AJ, Dyck PJ, Espinosa R. History of standard scoring, notation, and summation of neuromuscular signs. A current survey and recommendation. Journal of the peripheral nervous system : JPNS. 2005 Jun:10(2):158-73 [PubMed PMID: 15958127]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrancel PC, Francel TJ, Mackinnon SE, Hertl C. Enhancing nerve regeneration across a silicone tube conduit by using interposed short-segment nerve grafts. Journal of neurosurgery. 1997 Dec:87(6):887-92 [PubMed PMID: 9384400]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSilbermann-Hoffman O, Teboul F. Post-traumatic brachial plexus MRI in practice. Diagnostic and interventional imaging. 2013 Oct:94(10):925-43. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.08.013. Epub 2013 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 24035438]

Veronesi BA, Rodrigues MB, Sambuy MTC, Macedo RS, Cho ÁB, Rezende MR. USE OF MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING TO DIAGNOSE BRACHIAL PLEXUS INJURIES. Acta ortopedica brasileira. 2018 Mar-Apr:26(2):131-134. doi: 10.1590/1413-785220182602187223. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29983631]

Takagi T, Nakamura M, Yamada M, Hikishima K, Momoshima S, Fujiyoshi K, Shibata S, Okano HJ, Toyama Y, Okano H. Visualization of peripheral nerve degeneration and regeneration: monitoring with diffusion tensor tractography. NeuroImage. 2009 Feb 1:44(3):884-92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.022. Epub 2008 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 18948210]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrant GA, Britz GW, Goodkin R, Jarvik JG, Maravilla K, Kliot M. The utility of magnetic resonance imaging in evaluating peripheral nerve disorders. Muscle & nerve. 2002 Mar:25(3):314-31 [PubMed PMID: 11870709]

Winfree CJ. Peripheral nerve injury evaluation and management. Current surgery. 2005 Sep-Oct:62(5):469-76 [PubMed PMID: 16125601]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSpinner RJ, Kline DG. Surgery for peripheral nerve and brachial plexus injuries or other nerve lesions. Muscle & nerve. 2000 May:23(5):680-95 [PubMed PMID: 10797390]

Millesi H. Reappraisal of nerve repair. The Surgical clinics of North America. 1981 Apr:61(2):321-40 [PubMed PMID: 7233326]

Lin MY, Manzano G, Gupta R. Nerve allografts and conduits in peripheral nerve repair. Hand clinics. 2013 Aug:29(3):331-48. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2013.04.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23895714]

Rosson GD, Williams EH, Dellon AL. Motor nerve regeneration across a conduit. Microsurgery. 2009:29(2):107-14. doi: 10.1002/micr.20580. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18942644]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMidha R. Nerve transfers for severe brachial plexus injuries: a review. Neurosurgical focus. 2004 May 15:16(5):E5 [PubMed PMID: 15174825]

SUNDERLAND S. A classification of peripheral nerve injuries producing loss of function. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1951 Dec:74(4):491-516 [PubMed PMID: 14895767]

Robinson LR. Traumatic injury to peripheral nerves. Muscle & nerve. 2000 Jun:23(6):863-73 [PubMed PMID: 10842261]

Ciaramitaro P, Mondelli M, Logullo F, Grimaldi S, Battiston B, Sard A, Scarinzi C, Migliaretti G, Faccani G, Cocito D, Italian Network for Traumatic Neuropathies. Traumatic peripheral nerve injuries: epidemiological findings, neuropathic pain and quality of life in 158 patients. Journal of the peripheral nervous system : JPNS. 2010 Jun:15(2):120-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00260.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20626775]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKongcharoensombat W, Wattananon P. Risk of Axillary Nerve Injury in Standard Anterolateral Approach of Shoulder: Cadaveric Study. Malaysian orthopaedic journal. 2018 Nov:12(3):1-5. doi: 10.5704/MOJ.1811.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30555639]

De Pellegrin M, Fracassetti D, Moharamzadeh D, Origo C, Catena N. Advantages and disadvantages of the prone position in the surgical treatment of supracondylar humerus fractures in children. A literature review. Injury. 2018 Nov:49 Suppl 3():S37-S42. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.09.046. Epub 2018 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 30286976]

Chandawarkar RY, Cervino AL, Pennington GA. Management of iatrogenic injury to the spinal accessory nerve. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2003 Feb:111(2):611-7; discussion 618-9 [PubMed PMID: 12560682]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence