Introduction

A lung abscess is characterized as a localized collection of pus or necrotic tissue within the lung parenchyma, resulting in a cavity. Once a bronchopulmonary fistula develops, this cavity often exhibits an air-fluid level. Lung abscesses belong to the broader category of lung infections, including lung gangrene and necrotizing pneumonia, with the latter marked by multiple abscess formations.[1] Lung abscesses are typically categorized based on duration as either an acute abscess, which resolves in less than 6 weeks, or a chronic abscess, which persists for more than 6 weeks. A lung abscess may also be classified according to the underlying etiology. Primary lung abscess results from oropharyngeal secretion aspiration. Aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions may be secondary to various conditions, including dental or periodontal infections, sinusitis, altered states of consciousness, swallowing disorders, gastroesophageal reflux disease, frequent vomiting, necrotizing pneumonia, or immunocompromised individuals. Secondary lung abscesses arise from pulmonary conditions, including bronchial obstructions (eg, tumors, foreign bodies, or enlarged lymph nodes), existing lung conditions (eg, bronchiectasis, bullous emphysema, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, or lung contusions). A lung abscess may also be classified according to the pathophysiologic mechanism of spread from extrapulmonary sites, which can be hematogenous (eg, abdominal sepsis, infective endocarditis, infected catheters, or septic thromboembolisms) or direct (eg, bronchoesophageal fistulas or subphrenic abscesses).[2]

Early symptoms mimic pneumonia, including fever, chills, cough, night sweats, and chest pain, with a productive cough developing as a hallmark sign. Diagnostic imaging, including computed tomography (CT) scans and thoracic ultrasounds, is essential for characterizing lung abscesses. Furthermore, additional diagnostic studies (eg, sputum examination and bronchoscopy) are crucial for identifying the causative agents and differentiating lung abscesses from other conditions eg, cavitary tuberculosis and lung carcinoma. Complications can include pyopneumothorax or pleural empyema, especially in immunocompromised patients. Management often begins with empiric antibiotic therapy targeting a broad range of organisms, with adjustments made based on specific pathogens identified. Poor prognostic factors include old age, severe comorbidities, and immunosuppression. Surgical or percutaneous interventions may be necessary for abscesses larger than 6 cm or when medical therapy fails. Treatment duration is generally around 3 weeks, with a switch to oral antibiotics once the patient stabilizes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Primary lung abscesses are generally solitary and develop in otherwise healthy patients without preexisting medical conditions. In contrast, secondary lung abscesses arise in individuals with underlying or predisposing conditions; often, secondary lung abscesses comprise multiple abscess collections. The abscess can be described as nonspecific if no likely pathogen is recognized in the expectorated sputum or as a putrid abscess if the cause is presumed to be an anaerobic bacteria. The classification depends on the microorganism causing the abscess. In the majority of cases, the causative pathogen is polymicrobial, which includes anaerobic bacteria (eg, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, or streptococci).[3] A monomicrobial lung abscess is typically caused by streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Hemophilus influenzae type b, Nocardia, or Actinomyces.[4][5]

In patients with alcohol use disorder, the most common underlying organisms of a lung abscess include Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Actinomyces. Poor dental hygiene is an independent risk factor for the development of lung abscesses.[6] The incidence of Mycobacterium abscessus complex infection is greater in lung transplant recipients than in other solid organ transplant recipients. This increased incidence is primarily because lung transplant recipients need higher levels of immunosuppression posttransplant than other solid organ transplant recipients. Additionally, lung transplant recipients possess numerous donor-derived dendritic cells capable of activating T-cells and may encounter environmental antigens that could lead to graft rejection.[7]

Epidemiology

Some of the most common factors that predispose a patient to develop a lung abscess include:

Pathophysiology

In most cases, patients have primary lung abscesses due to aspiration of oropharyngeal contents with anaerobes. These primary lung abscesses typically initially start as aspiration pneumonia and are later complicated by pneumonitis, progressing to tissue necrosis in 1 to 2 weeks if left untreated.[9] Bronchogenic causes include bronchial obstruction by a tumor, foreign body, enlarged lymph nodes, aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions, and congenital malformation. In remaining cases, a lung abscess results from the hematogenous spread of an extrapulmonary pathology, including abdominal sepsis, infective endocarditis, and septic thromboembolism.

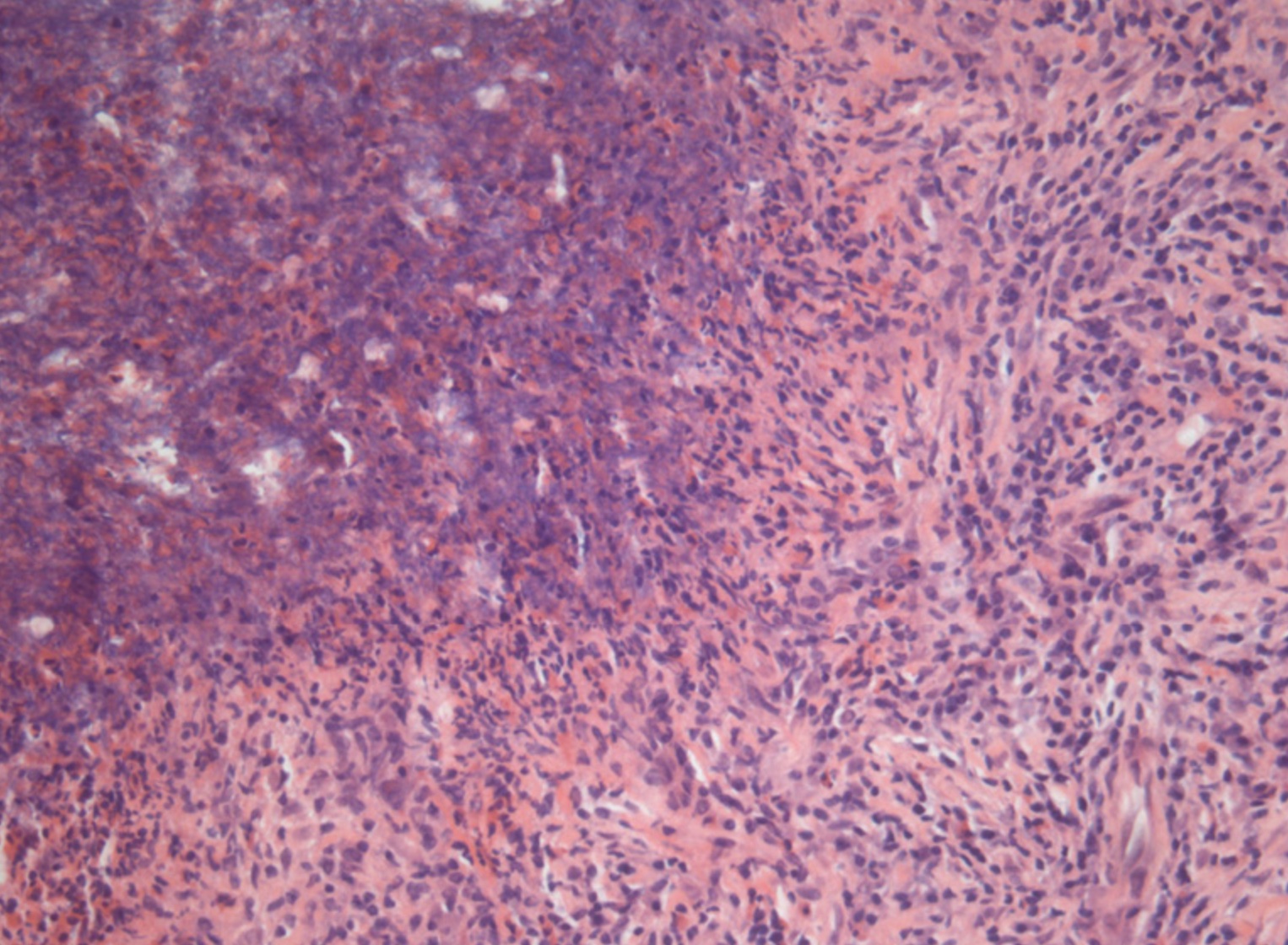

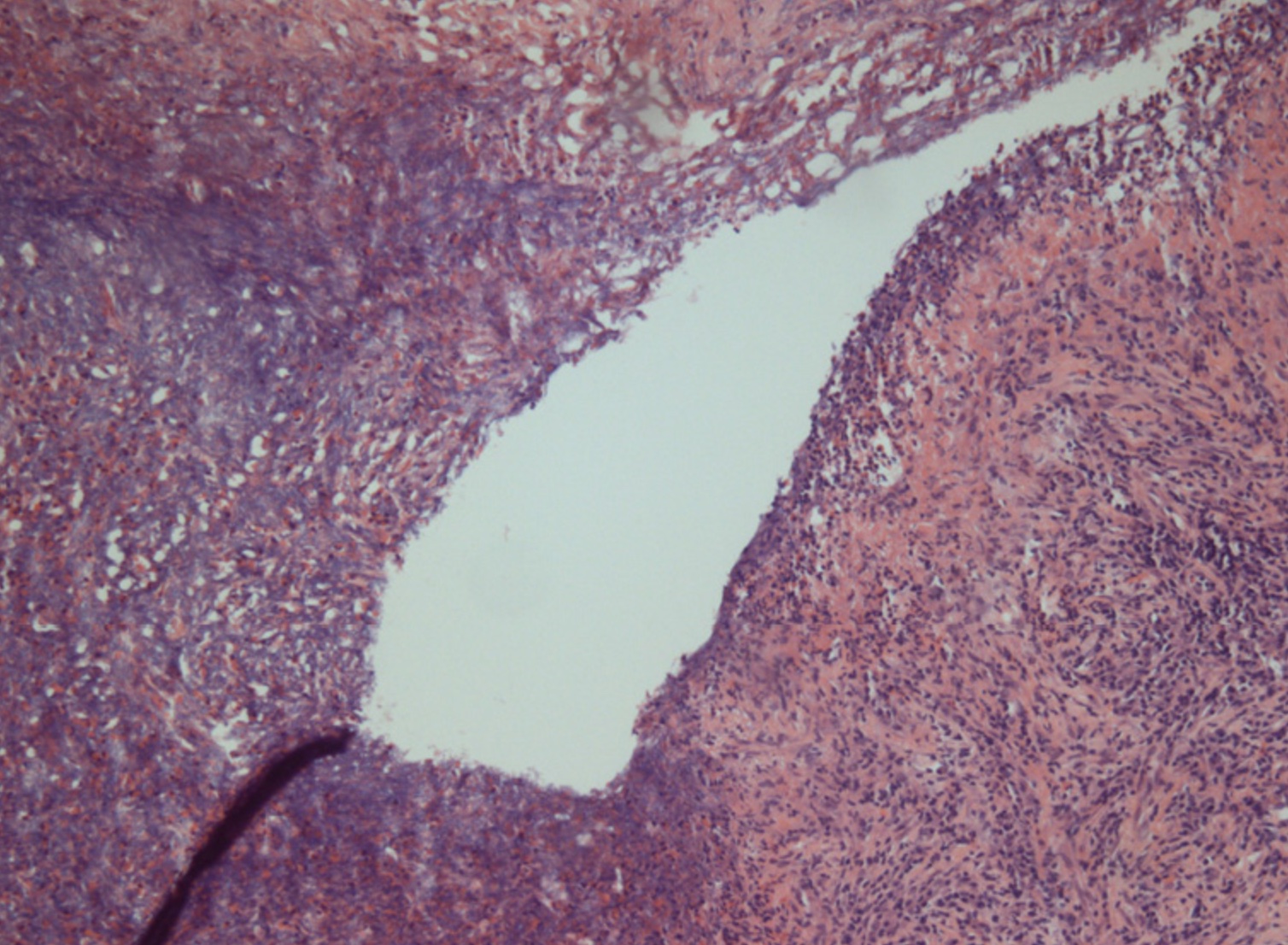

Histopathology

Acute lung abscesses are typically characterized by poorly defined borders within the lung parenchyma and are filled with thick necrotic debris. Histologically, the central region of an acute abscess contains necrotic tissue intermingled with necrotic granulocytes and bacteria. Surrounding this central area are intact neutrophilic granulocytes, dilated blood vessels, and inflammatory edema (Image. Acute Lung Abscess). In contrast, chronic lung abscesses often have an irregular, star-like shape with well-defined borders in the lung parenchyma. These abscesses contain a grayish lining or thick debris. The center of a chronic abscess is filled with pus, with or without bacteria. Surrounding the abscess is a pyogenic membrane through which white blood cells migrate into the abscess cavity. The area around the pyogenic membrane includes lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes within the connective tissue.[2] (Image. Chronic Lung Abscess)

History and Physical

Early signs and symptoms of a lung abscess are similar to pneumonia and include fever, chills, cough, night sweats, dyspnea, weight loss, fatigue, chest pain, and occasionally anemia. Initially, the cough is nonproductive, but it becomes productive when bronchial communication develops, a hallmark sign of lung abscess. This productive cough may sometimes be accompanied by hemoptysis. Differential diagnoses for lung abscesses include conditions like cavitary tuberculosis and mycoses, although these rarely show the radiological sign of a gas-liquid level. Cavitating bronchial carcinomas (eg, squamous cell or small cell carcinomas) typically present with thicker, more irregular walls than infectious lung abscesses. The absence of fever, purulent sputum, and leukocytosis can suggest a carcinoma rather than an infectious disease.

Evaluation

Chest radiographs and CT aid in the diagnosis of a lung abscess. Differentiating between lung abscesses and pulmonary cystic lesions, including intrapulmonary bronchial cysts, sequestration, or secondary infected emphysematous bullae, can be challenging. However, the lesion's location and clinical signs often guide the diagnosis. Localized pleural empyema can be distinguished using a CT scan (Image. Computed Tomography of a Lung Abscess) or ultrasound. The radiological sign of an air-fluid level can also be seen in hydatid cysts of the lung.[10]

Sputum examination helps identify microbiological agents or confirm bronchial carcinoma. Microbiologic analysis of sputum can potentially assist in management. If the patient presents with risk factors for fungi or mycobacteria in their history, particular cultures should be requested.[11] Diagnostic bronchoscopy is crucial for obtaining material for microbiological examination and confirming an intrabronchial cause of the abscess, such as a tumor or foreign body. Pleural fluid analysis and bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage also have been utilized in rare cases.[12] Lung abscesses are more prone to develop over the posterior segment of the right upper lobe and middle lobe followed by the superior segment of the right lower lobe and sometimes of the left lung in case of aspiration of oropharyngeal contents.[13] Complicated lung abscess can cause pyopneumothorax or pleural empyema. In such cases, pleural fluid analysis can aid in diagnosis. Lung abscesses in patients who are immunocompromised have an increased risk of complications. However, immunocompetent patients with adequate treatment have a decreased risk of complications and usually resolve in 3 weeks. Furthermore, in cases of lung abscesses secondary to hematologic spread, blood cultures and echocardiography are essential in determining the appropriate management.

Treatment / Management

Clinicians should consider empiric antibiotic therapy in patients suspected of having a lung abscess. Empiric coverage should target colonized organisms in the upper airway and oropharynx, including gram-positive cocci, gram-negative cocci, and aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. If the patient is exposed to healthcare set 3 months before the presentation, coverage for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) should be considered. Atypical organisms can be found in the setting of an abscess that is not improving with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Poor prognostic factors include individuals who are older or with severe comorbidities, immunosuppression, bronchial obstruction, and neoplasms. Beta-lactamase inhibitors (eg, ticarcillin-clavulanate, ampicillin-sulbactam, amoxicillin-clavulanate, and piperacillin-tazobactam) are the preferred initial empiric antibiotic therapy followed by imipenem or meropenem.[14]

Clindamycin, as an empiric treatment for lung abscess, is no longer recommended given the risk of Clostridium difficile infection, but it remains an alternative for penicillin-allergic patients. For MRSA, vancomycin or linezolid are preferred. Daptomycin has no activity against pulmonary infections.[15] For methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, preferred pharmacologic treatments are cefazolin 2 g intravenously (IV) every 8 hours, nafcillin 2 gm IV every 4 hours, or oxacillin 2 gm IV every 4 hours. Dosing adjustment is considered in patients with compromised renal function. Antibiotic duration is usually around 3 weeks but varies depending on clinical response. Clinicians should consider switching to oral antibiotics once patients are afebrile, stable, and able to tolerate an oral diet. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is the drug of choice for oral antibiotics for lung abscesses.[16] Metronidazole, as a single therapy, does not appear particularly useful due to polymicrobial flora.[17](A1)

Abscesses larger than 6 cm are unlikely to resolve with antibiotic therapy alone and might require surgical or percutaneous intervention.[2] In patients who fail to respond to medical therapy, surgical intervention is considered with lobectomy or pneumonectomy.[18] In patients who are poor surgical candidates, percutaneous and endoscopic drainage is considered.[19] When the clinical response is inadequate, associated conditions or alternative diagnoses are considered, especially for certain fungi and mycobacteria. Empyema sometimes might be misdiagnosed as a parenchymal abscess. Antibiotic administration has proven beneficial in the case of chronic lung abscesses.[20] Additionally, in the case of hematologic causes of lung abscess, any underlying conditions (eg, infective endocarditis, septic thromboembolism) should be thoroughly treated.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses that should be considered when evaluating patients with a lung abscess include:

- Excavating bronchial carcinoma (squamocellular or microcellular)

- Excavating tuberculosis

- Localized pleural empyema

- Infected emphysematous bullae

- Cavitary pneumoconiosis

- Hiatal hernia

- Pulmonary hematoma

- Hydatid cyst of the lung

- Cavitary infarcts of lung

- Polyangiitis with granulomatosis (Wegener granulomatosis)

- Foreign body aspiration

- Septic pulmonary emboli

Prognosis

In most cases, empiric antibiotic therapy successfully treats primary lung abscesses, followed by targeted therapy depending on gram stain and culture results, with an approximately 90% cure rate. Secondary abscesses require treatment of the underlying cause to improve the outcome. The prognosis of patients with secondary lung abscesses is poor, especially in immunocompromised patients and patients with bronchial neoplasm, with a mortality rate of approximately 75%.[21]

Complications

Complications primarily develop secondary to the underrecognition or inappropriate treatment of a lung abscess's underlying etiology. Complications include abscess rupture into the pleural space, pleural fibrosis, trapped lung, respiratory failure, bronchopleural fistula, and pleurocutaneous fistula.[22]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient and caregiver education regarding the mitigation of aspiration risk factors through strategies including avoiding excessive alcohol intake, proper dental care, and elevation of the head of the bed is essential to preventing the development of a lung abscess. Clinicians should also educate patients and their families about prompt recognition of lung abscess symptoms, including fever, shortness of breath, and productive or nonproductive coughs. Antibiotic therapy compliance and monitoring for adverse effects of medications should be emphasized to avoid complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

The following key underlying etiologies should be kept in mind when managing a lung abscess:

Aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions

- Dental and periodontal infection

- Paranasal sinusitis

- Altered level of consciousness

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Frequent vomiting

- Intubated patients

- Patients with tracheostomy

- Vocal cord paralysis

- Alcohol use disorder

- Cerebrovascular accident

Hematogenic dissemination

- Abdominal sepsis

- Infective endocarditis

- Intravenous drug abuse

- Infected cannula or central venous catheter

- Septic thromboembolisms

Coexisting lung diseases

- Bronchiectasis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Bullous emphysema

- Bronchial obstruction by a tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes

- Congenital malformations

- Infected pulmonary infarcts

- Pulmonary contusion

- Bronchoesophageal fistula

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of lung abscesses requires a coordinated interprofessional approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals to enhance patient-centered care, outcomes, patient safety, and team performance. Identifying patients at high risk for aspiration and implementing strict aspiration precautions is crucial, as inhalation of oropharyngeal contents is a significant risk factor for developing lung abscesses. Physicians and advanced practitioners play a pivotal role in diagnosing and treating aspiration pneumonia promptly to prevent progression to lung abscesses. Nurses are vital in recognizing and communicating the need for increased monitoring of patients with restricted mobility, including those with cerebral vascular accidents, severe Parkinson's disease, severe Alzheimer's disease, or postoperative status, who are at higher risk for aspiration. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring appropriate antibiotic regimens are administered, considering potential drug interactions and contraindications, especially in complex cases involving broad-spectrum antibiotics or patients with a history of healthcare exposure requiring MRSA coverage. Physical therapists and respiratory therapists provide essential chest physiotherapy and physical therapy to prevent bedbound status and respiratory muscle fatigue, thereby reducing the risk of aspiration.

Interprofessional communication and care coordination are essential for the timely recognition and management of lung abscesses. This involves regular team meetings, shared electronic health records for real-time information exchange, and collaborative decision-making to adjust treatment plans based on patient responses. Diagnostic tools such as chest radiographs, CT scans, sputum examination, and bronchoscopy require input from radiologists and pulmonologists to guide accurate diagnosis and treatment. In complex cases, surgical interventions may be necessary, requiring coordination with thoracic surgeons. Vigilant monitoring and early intervention can prevent complications such as pyopneumothorax or pleural empyema in immunocompromised patients. By integrating the expertise and skills of various healthcare professionals, the team can ensure comprehensive care, improve clinical outcomes, and maintain patient safety throughout the treatment of lung abscesses.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Suleac M, Naranjo S, Djassi M, Lavadinho I. Necrotizing Pneumonia With Extensive Lobar Cavitation. Cureus. 2024 Mar:16(3):e56437. doi: 10.7759/cureus.56437. Epub 2024 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 38638719]

Kuhajda I, Zarogoulidis K, Tsirgogianni K, Tsavlis D, Kioumis I, Kosmidis C, Tsakiridis K, Mpakas A, Zarogoulidis P, Zissimopoulos A, Baloukas D, Kuhajda D. Lung abscess-etiology, diagnostic and treatment options. Annals of translational medicine. 2015 Aug:3(13):183. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.07.08. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26366400]

Bartlett JG, Gorbach SL, Tally FP, Finegold SM. Bacteriology and treatment of primary lung abscess. The American review of respiratory disease. 1974 May:109(5):510-8 [PubMed PMID: 4595941]

FISHER AM, TREVER RW, CURTIN JA, SCHULTZE G, MILLER DF. Staphylococcal pneumonia; a review of 21 cases in adults. The New England journal of medicine. 1958 May 8:258(19):919-28 [PubMed PMID: 13541686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang JL, Chen KY, Fang CT, Hsueh PR, Yang PC, Chang SC. Changing bacteriology of adult community-acquired lung abscess in Taiwan: Klebsiella pneumoniae versus anaerobes. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005 Apr 1:40(7):915-22 [PubMed PMID: 15824979]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencevan Brummelen SE, Melles D, van der Eerden M. [A lung abscess caused by bad teeth]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor tandheelkunde. 2018 Jul:125(7-8):384-387. doi: 10.5177/ntvt.2018.07/08.18160. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30015813]

Osman L, Lopez C, Natori Y, Anjan S, Bini Viotti J, Simkins J. Therapy of Mycobacterium abscessus Infections in Solid Organ Transplant Patients. Microorganisms. 2024 Mar 16:12(3):. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12030596. Epub 2024 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 38543646]

Hinchcliffe N, Benbow A, Moshiri T, Thompson J, Venkatesan P. Isolation of Raoultella ornithinolytica in a HIV positive patient with a lung abscess. Access microbiology. 2022 Aug:4(6):acmi000365. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000365. Epub 2022 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 36004361]

Guo W, Gao B, Li L, Gai W, Yang J, Zhang Y, Wang L. A community-acquired lung abscess attributable to odontogenic flora. Infection and drug resistance. 2019:12():2467-2470. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S218921. Epub 2019 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 31496760]

Deng A, Zhang Z, He M, Zhou T. Acute lung abscess with multiple infections: A refractory case. Asian journal of surgery. 2023 Aug:46(8):3364-3365. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2023.03.084. Epub 2023 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 36973142]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDragonieri S, Bikov A, Capuano A, Scarlata S, Carpagnano GE. Methodological Aspects of Induced Sputum. Advances in respiratory medicine. 2023 Sep 27:91(5):397-406. doi: 10.3390/arm91050031. Epub 2023 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 37887074]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHapsari BD, Melita M, Ismail AR, Djatmika FN. A large primary lung abscess due to Klebsiella oxytoca: How critical the combination between early antibiotic therapy and bronchoscopy? Narra J. 2023 Aug:3(2):e169. doi: 10.52225/narra.v3i2.169. Epub 2023 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 38450261]

Landay MJ, Christensen EE, Bynum LJ, Goodman C. Anaerobic pleural and pulmonary infections. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1980 Feb:134(2):233-40 [PubMed PMID: 6766225]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoldstein EJ, Citron DM, Warren Y, Tyrrell K, Merriam CV. In vitro activity of gemifloxacin (SB 265805) against anaerobes. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1999 Sep:43(9):2231-5 [PubMed PMID: 10471570]

DeLeo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet (London, England). 2010 May 1:375(9725):1557-68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61999-1. Epub 2010 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 20206987]

Fernández-Sabé N, Carratalà J, Dorca J, Rosón B, Tubau F, Manresa F, Gudiol F. Efficacy and safety of sequential amoxicillin-clavulanate in the treatment of anaerobic lung infections. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2003 Mar:22(3):185-7 [PubMed PMID: 12649717]

Perlino CA. Metronidazole vs clindamycin treatment of anerobic pulmonary infection. Failure of metronidazole therapy. Archives of internal medicine. 1981 Oct:141(11):1424-7 [PubMed PMID: 7025777]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHino H, Yasuhara Y, Nakahata K, Utsumi T, Maru N, Matsui H, Taniguchi Y, Saito T, Tsuta K, Okada H, Murakawa T. Emergency right lower lobectomy for severe pulmonary abscess in a pregnant woman at the 25th week of gestation: a case report. Surgical case reports. 2024 May 23:10(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s40792-024-01932-8. Epub 2024 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 38780682]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRäsänen J, Bools JC, Downs JB. Endobronchial drainage of undiagnosed lung abscess during chest physical therapy. A case report. Physical therapy. 1988 Mar:68(3):371-3 [PubMed PMID: 3347655]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAinge-Allen HW, Lilburn PA, Moses D, Chen C, Thomas PS. Antibiotic instillation for a chronic lung abscess. Respiratory medicine case reports. 2020:29():100991. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2019.100991. Epub 2019 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 31908918]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePohlson EC, McNamara JJ, Char C, Kurata L. Lung abscess: a changing pattern of the disease. American journal of surgery. 1985 Jul:150(1):97-101 [PubMed PMID: 4014575]

Boot M, Archer J, Ali I. The diagnosis and management of pulmonary actinomycosis. Journal of infection and public health. 2023 Apr:16(4):490-500. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2023.02.004. Epub 2023 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 36801629]