Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Edema

Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Edema

Introduction

Heart failure is a growing public health problem that is now the most common cause of hospitalizations in the United States among patients aged 65 and older. The growing prevalence of heart failure is primarily attributed to an aging population and a rise in risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. Healthcare professionals should be familiar with the pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment of heart failure because of the morbidity, mortality, and projected increased prevalence of the condition.[1][2][3]

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome and encompasses a constellation of symptoms secondary to impaired cardiac function; there are numerous etiologies for impaired heart function. The causative factors for heart failure are generally divided into structural or functional categories. Patients who have heart failure can also be classified based on the stage or degree of heart failure and symptoms, including episodes of acute exacerbation and pulmonary edema. Heart failure can be divided into 2 broad categories: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpE) and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). The incidence of HFpEF increases with age, and most cases of heart failure in older patients are due to HFpEF.[1][3]

Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is a common and potentially fatal cause of cardiac dysfunction that can present with acute respiratory distress. In ADHF, pulmonary edema and the rapid accumulation of fluid within the interstitial and alveolar spaces lead to significant dyspnea and respiratory decompensation. There are many different causes of pulmonary edema, though cardiogenic pulmonary edema is usually a result of acutely elevated cardiac filling pressures.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

In the United States, there are many causes of heart failure—the most common of which is coronary artery disease. Identifying the risk factors for heart failure is important because this condition is preventable. Acknowledging the preventable nature of heart failure, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have updated their classification systems to identify patients without structural abnormalities early, enabling timely and appropriate treatment. Treatment of systolic and diastolic hypertension concurrently in alignment with contemporary guidelines reduces the risk of heart failure by approximately 50%.[1]

Risk Factors for Heart Failure

- Coronary artery disease (CAD)

- Connective tissue disorders (ie, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus)

- Endocrine disorders (ie, diabetes mellitus, thyroid function disorders, growth hormone deficiency)

- Hypertension

- High-output conditions (ie, anemia, Paget disease)

- Valvular heart disease

- Metabolic causes (ie, obesity)

- Myocarditis (ie, secondary to human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, medications, or viruses)

- Infiltrative disorders (ie, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis)

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy

- Stress cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo)

- Valvular heart disease

- Medications (ie, amphetamines, anabolic steroids)

- Tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy

- Toxins (ie, cocaine, alcohol)

- Nutritional deficiency (ie, L-carnitine deficiency, thiamine) [1]

Risk Factors for Acute Heart Failure and Flash Pulmonary Edema

Acute heart failure is the worsening of heart failure symptoms to the point that the patient requires intensification of therapy and intravenous treatment. Acute heart failure can be dramatic and rapid in onset, such as flash pulmonary edema, or more gradual with the worsening of symptoms over time until a critical point of decompensation is reached. For those with a history of preexisting heart failure, there is often a clear trigger for decompensation.[3][4]

Potential Triggers of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure and Flash Pulmonary Edema

Epidemiology

Heart failure is a major public health problem. This condition is now the most common cause of hospitalization in the United States among patients aged 65 and older, and approximately 91,500 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed each year. The increasing prevalence of heart failure is most likely secondary to the aging of the population, increased risk factors, better outcomes for acute coronary syndrome survivors, and a reduction in mortality secondary to improved management of chronic conditions. Further, incidence rates for heart failure increase with age for both sexes.[1][2][3][5]

The lifetime risk of developing heart failure for those 40 and older residing in the United States is 20%. The risk and incidence of heart failure continue to increase from 20 per 1000 people aged 60 to 65 to over 80 per 1000 people aged 80 and older. There are also differences in risk for heart failure based on the population, with Black individuals having the highest risk and greater 5-year mortality for heart failure than the White population in the United States. The European Society of Cardiology states that the prevalence of heart failure is 1% to 2% and rises to greater than 10% in the population of those aged 70 and older.[1][3]

Heart Failure Statistics

- Heart failure survival has improved over time, yet the absolute 5-year mortality rates from diagnosis for heart failure have remained at 50%

- Heart failure is the number 1 diagnosis among all hospitalizations, and the cost of annual heart failure care exceeds $30 billion every year.

- Most of the cost spent on heart failure patients is for hospitalizations and readmissions.[1]

Acute Heart Failure

Although consensus guidelines tend to use the term heart failure to refer to those with established chronic disease, acute heart failure is defined as a more rapid onset of signs and symptoms or the gradual worsening of chronic symptoms that necessitate intravenous treatment. Acute heart failure exacerbation that requires hospitalization tends to occur in the older adult population, with a mean age of 79 years and a slightly higher preponderance of women affected than men.[1][2][3] Data from the United Kingdon National Heart Failure Audit show mortality rates of approximately 10% during the index admission, 30-day postdischarge mortality of 6.5%, and 1-year mortality of 30%.[3]

Pathophysiology

Heart failure can arise from various cardiovascular or metabolic abnormalities. Still, in most cases, clinical symptoms are due to left ventricular dysfunction and may be preserved or reduced when left ventricular dysfunction is present. The ejection fraction is a key measure often used to select patients for clinical trials and guide therapeutic decisions. In contrast, pulmonary edema seen in acute decompensated heart failure results from the dysregulation of pulmonary fluid homeostasis, disrupting the balance of forces controlling fluid movement into the alveolar space.[4][6]

History and Physical

Heart failure is predominately a clinical diagnosis. The presentation of heart failure may vary based on each patient; therefore, it is essential to consider the following during the history and physical:

- History: If the patient has a history of past heart failure, ask if this is the same presentation as when they had previous episodes of heart failure or an acute decompensation.

- Symptom Causes: Consider noncardiac and other causes of the patient's symptoms, as it is important to ensure a broad differential diagnosis and avoid anchoring bias, premature closer, and diagnostic inertia.

- Heart failure symptoms:

- Increasing dyspnea (on exertion, on lying flat or at rest, exercise intolerance)

- Increasing leg swelling, ascites, edema

- Increased body weight

- Palpitations, automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks (associated with worse prognosis)

- Chest pain, fatigue

- Duration of Illness, recent or frequent hospitalizations for heart failure

- Medications or diet changes

- Anorexia, cachexia, or early satiety (associated with worse prognosis)

- Symptoms of transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism (indicate a possible need for anticoagulation)

- Social history and family history (to assess for possible familial cardiomyopathy, alcohol, or other cause

- Travel history (exposure risk to some tropical diseases) [1][6]

Physical Examination

The physical examination should include the following:

- Vital signs: Assess blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation, and respiratory rate. Vital signs are important in helping develop and refine the differential diagnosis and help the healthcare professional tailor the physical examination better.

- Check patient weight: The patient's weight and body mass index should be checked during each office visit. The information can be used to track response to treatment and the potential progression of heart failure or acute decompensated heart failure. Losing weight can also be a warning sign of worsening heart failure.

- Assessment of jugulovenous distension: Jugulovenous distension can be a marker for fluid overload. The patient should lie at a 45-degree angle in bed to get an accurate assessment.

- Pulse: Assess the regularity and strength of the pulse.

- Cardiac Examination

- Extra heart sounds (ie, S3 is associated with a worse prognosis), murmurs

- Size and location of maximal cardiac impulse (can suggest ventricular enlargement if displaced)

- Presence of right ventricular heave

- Pulmonary Examination: Check respiratory rate, rhonchi, and rales (note: pleural effusions can mask and reduce breath sounds, and rhonchi or rales may be less prominent).

- Abdominal examination: Check for ascites, hepatomegaly, hepatojugular reflux.

- Lower extremity examination: Assess for peripheral edema and skin temperature (cool lower extremities may suggest worse cardiac output).[1][6]

Evaluation

Classification of Heart Failure

Classification is one of the key determinants of evaluating and treating heart failure. When a patient is in acute or decompensated heart failure, our focus is on expeditious identification and treatment of life threats. Different classification schemes are available when evaluating chronic heart failure. The classification scheme used to categorize the type and degree of heart failure is based on the presentation and affects the treatment and prognosis of the condition. Heart failure classification schemes are generally based on 1 of the following:

- Anatomic findings (ie, heart failure with different degrees of ejection fraction)

- The chamber of the heart involved (including functional)

- Symptoms of the patient

All heart failure patients should also be classified based on the American College Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) stages of heart failure, a New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification.[1][6]

ACCF/AHA Stages of Heart Failure

The risk of heart failure defines the ACC/AHA stages of heart failure, the presence of active heart failure, and whether structural heart disease is present. The higher the classification, the greater the treatment and interventions the patient may require.

- A: No structural heart disease present, high risk for heart failure, and asymptomatic

- B: Structural heart disease present, asymptomatic

- C: Structural heart disease present and current or previous symptoms of heart failure

- D: Heart failure that is refractory and requires specialized interventions [6]

NYHA Functional Classification of Heart Failure

The NYHA classification is a functional classification of heart failure and is based on how much the patients' symptoms limit their physical activity and to what degree physical activity can cause the person to become symptomatic. The grading scale is from I (least severe)to grade IV (the most severe) where the patient cannot perform physical activity and has symptoms at rest.[6]

Diagnostic Tests

Testing for heart failure in patients should be focused on the patient's symptoms, clinical suspicion, and pre-existing or current stage of heart failure. Ordering multiple routine tests should be avoided in all patients with heart failure. Basic tests that should merit consideration for all patients evaluated for heart failure are the following:

- Serum electrolytes and kidney function

- Complete blood count

- Lipid level

- Liver function tests

- Troponin level if there is concern that myocardial injury is the cause of symptoms

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- An electrocardiogram

Other tests that may be considered based on the severity and classification of the patient's condition are:

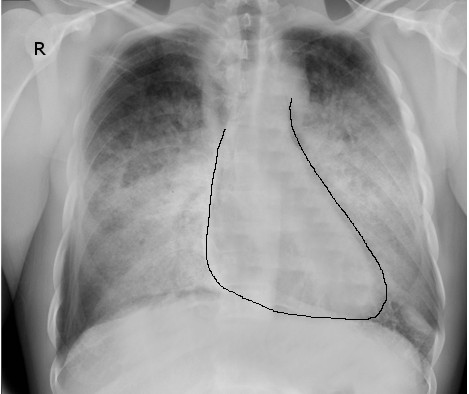

- Chest x-rays assess for signs of pulmonary congestion or edema in acute decompensated heart failure (see Image. Congestive Heart Failure, Radiograph).

- Biomarkers are used to assess patients with more complex symptoms than acute heart failure (ie, B-type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide).

For further information on the recommendations for evaluating heart failure, please see the American Heart Association and New York Heart Association classification-based heart failure guidelines.[1][2][6]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure and Pulmonary Edema

The focus of treatment for patients with heart failure is dependent on the severity of the symptoms and the stage of heart failure. When patients are in acute decompensated heart failure or flash pulmonary edema, the most important focus for therapeutic interventions is the enhancement of hemodynamic status through the reduction of vascular congestion and improving preload, afterload, and myocardial contractility.[2] In flash pulmonary edema, where there is a rapid onset of heart failure, the initial management and treatment goals are very similar to acute decompensated heart failure. Treatment options for acute decompensated heart failure and flash pulmonary edema are as follows:

- ABCs: As with all patients, it is crucial to assess airway, breathing, and circulation in the initial evaluation and initiate appropriate management based on patient status. In decompensated heart failure, patients should be hooked up to cardiorespiratory monitoring, have IV access and oxygen administered if hypoxic or tachypnoeic, have an electrocardiogram performed, and have labs drawn based on clinical suspicion and patient condition.

- Diuretics: Most patients presenting with heart failure have a form of volume overload. AHA and ACC guidelines recommend intravenous loop diuretic administration to treat fluid overload. Intravenous administration is preferred over oral diuretics to maximize the bioavailability of the medication and clinical effects. Furosemide is a common treatment for acute decompensated heart failure and flash-pulmonary edema because of its anti-vasoconstrictor and diuretic effects.[2][6]

- Vasodilators: Patients with acute decompensated heart failure with hypertension and acute pulmonary edema can benefit from treatment with vasodilators. Most vasodilators promote smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation to reduce preload and afterload through the cyclic guanine monophosphate pathway. Vasodilation relieves pulmonary vascular congestion and improves left ventricular preload and afterload. The common vasodilator medications used are nitroglycerin and sodium nitroprusside.[2][6]

- Nitroglycerin can be given transdermally, sublingually, or intravenously, depending on the patient's condition. In acute decompensation or flash pulmonary edema, nitroglycerin is best given sublingually or intravenously to allow for titration of effect.[2][6]

- Sodium nitroprusside is only given intravenously. Patients with renal dysfunction treated with sodium nitroprusside may need to have their cyanide levels monitored. Check with your pharmacist about guidelines for monitoring cyanide levels.[2][6]

- Ionotropic Medications: Additional treatment options for patients in cardiogenic shock or who have signs of end-organ dysfunction secondary to hypoperfusion. Inotropes should only be used as a treatment adjunct in acute decompensated heart failure since data from the ADHERE registry suggest increased mortality with use. Dobutamine and mllrinone are 2 inotropes that are more commonly used. Dobutamine is preferable for patients who are beta-blocker-naive, while milrinone is preferred for patients previously taking oral beta blockers who experience acute decompensation.[2][6]

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) and Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BIPAP): These are noninvasive methods of respiratory support to treat respiratory insufficiency secondary to pulmonary vascular congestion and pulmonary edema. The use of CPAP and BIPAP has reduced the need for intubation and mechanical ventilation in heart failure patients with acute respiratory decompensation. In situations where CPAP and BIPAP are ineffective in improving the patient's respiratory status, early intubation and mechanical ventilation should be considered to help prevent further decompensation and progression of symptoms.[7][8]

- Coronary revascularization: When performed in appropriately selected patients, revascularization can reduce mortality and morbidity by improving diastolic and systolic dysfunction. According to the AHAs 2013 congestive heart failure guidelines, coronary artery revascularization may be indicated as an intervention for heart failure patients with angina, left ventricle dysfunction, and CAD. Interventional cardiology should be consulted early for patients according to AHA recommendations.[2][6]

- Admission to inpatient service for further treatment and evaluation: Patients being treated for flash pulmonary edema should be admitted to the hospital with the level of monitoring and care appropriate for each case. For select patients with acute decompensated heart failure, it may be possible to treat them at home, depending on the severity of symptoms.[9] (B3)

The Medical Management of Heart Failure–Risk Factor Modification and Prevention of Acute Decompensation

While acute decompensated heart failure and flash pulmonary edema can be dramatic and require intensive care and aggressive therapy, the main focus of heart failure management is on helping prevent the progression of the disease and mitigate episodes of acute exacerbation. Medical practitioners often use the American Heart Association and the New York Heart Association stages of heart failure to guide the evidence-based treatment of heart failure. Treatment of early stages of chronic heart failure usually focuses on risk factor modification, and as the disease process progresses, it starts to include more aggressive interventions.

- Risk factor modification

- Dietary and lifestyle changes, such as decreased salt intake, reduced obesity, and smoking cessation

- Tighter control and management of hypertension, diabetes dyslipidemia, and other chronic diseases that can exacerbate CHF

- More aggressive intervention for those with a higher degree of CHF

- Echocardiography for patients with a higher risk of left ventricular ejection fraction reduction

- Implantable cardiac defibrillator placement, when indicated in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy at high risk of sudden death

For further information on the medical management of chronic heart failure, please refer to the American Heart Association and New York Heart Association guidelines.[1][2][1][6](B3)

Advanced Treatment Strategies for End-Stage Congestive Heart FailureFor select patients with end-stage heart failure, which is refractory to other treatment strategies, the option of mechanical circulatory support and cardiac transplantation should be considered. In mechanical circulatory support, for example, a left ventricular assist device is often used as a bridge therapy until a heart transplant is available. In certain situations, mechanical circulatory support is utilized as destination therapy. For patients who are not candidates for mechanical circulatory support or cardiac transplantation, palliative care and continuous inotropic support should be considered and discussed with the patient (see Image. Congestive Heart Failure).[1][10]

Differential Diagnosis

When patients present with acute decompensated heart failure or flash pulmonary edema, there are many different diagnoses to consider based on the risk factors for heart failure alone. Also important to consider are other potentially life-threatening causes of heart failure.

- Sepsis: Patients with sepsis are at risk of multiorgan system failure. Approximately 1 out of 3 patients with sepsis present with reversible left ventricular systolic dysfunction reduced ejection fracture, and 1 out of 2 patients with sepsis have left ventricular or right ventricular diastolic dysfunction. The cardiac dysfunction associated with sepsis can result in significantly increased mortality. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is associated with an increased mortality risk of 80%, and right ventricular diastolic dysfunction is associated with a 60% increased mortality.[11]

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome: This condition is characterized by acute respiratory failure and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, which could potentially mimic flash pulmonary edema.[11]

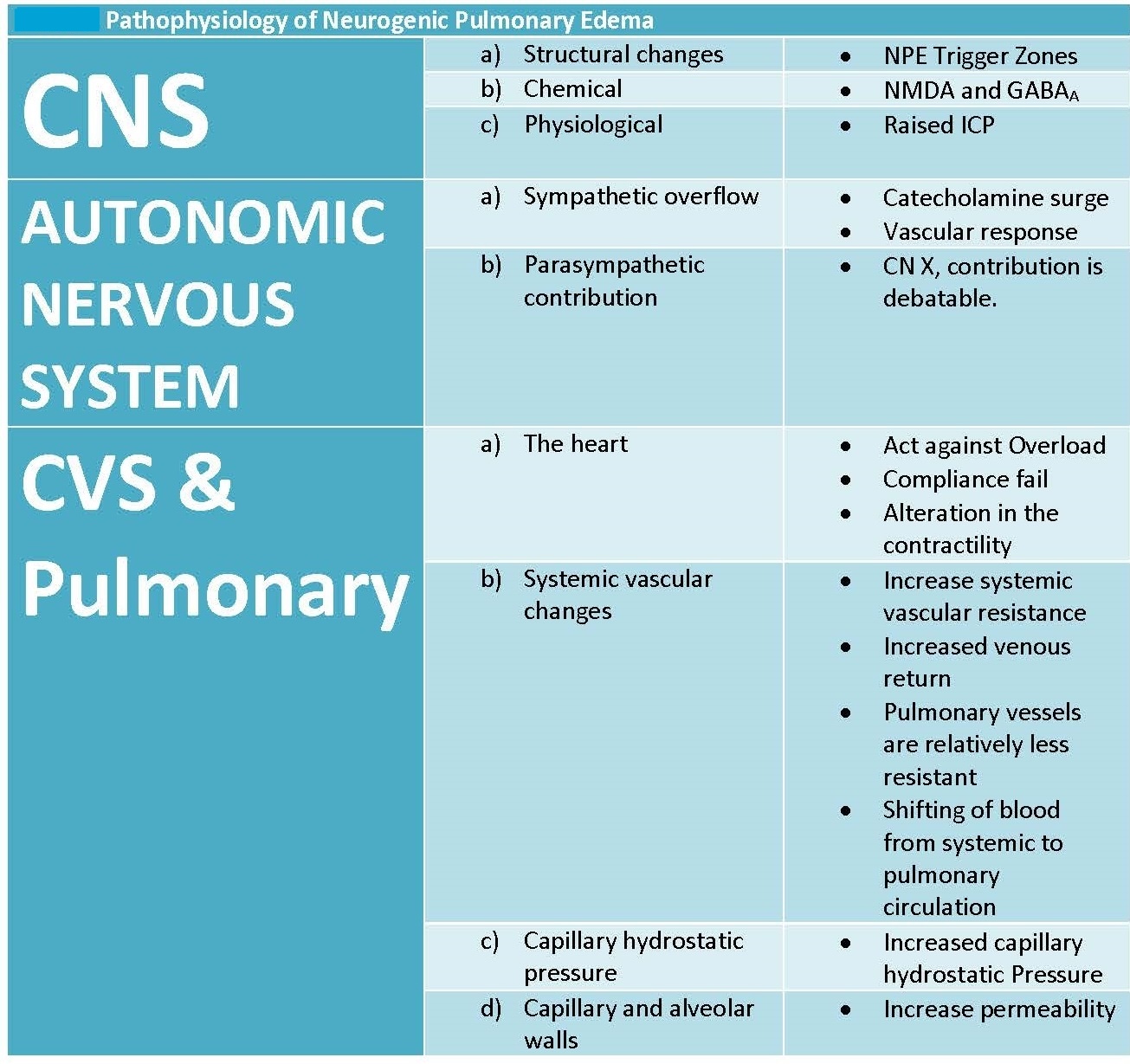

- Neurological causes: Hemispheric and hippocampal brain infarcts are associated with heart failure and sudden cardiac death. Infarct of certain areas of the brain tissue can result in a sympathetic storm, and loss of vasomotor homeostasis precipitates neurogenic pulmonary edema (see Image. Key Features in the Pathophysiology of Neurogenic Pulmonary Edema).[12]

- Pulmonary embolism: While a massive pulmonary embolism can cause acute cardiac dysfunction secondary to obstruction of blood flow, post-pulmonary embolism syndrome may also present with heart failure-type symptoms. Postpulmonary embolism syndrome and reduced exercise tolerance have been associated with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, arrhythmia, valvular dysfunction, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction.[13]

- Acute coronary syndrome: Acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction is a common cause of acute decompensated heart failure.

Prognosis

The diagnosis of heart failure alone can be associated with a mortality rate greater than many cancers. Despite advances made in heart failure treatments, the prognosis of the condition worsens over time, resulting in frequent hospital admissions and premature death. Results from one recent study showed that patients recently diagnosed with new-onset heart failure had a mortality rate of 20.2% at 1 year and 52.6% at 5 years. The 1- and 5-year mortality rates also increase significantly based on the patient's age. Another study had results showing that the 1- and 5-year mortality for patients at age 60 is 7.4% and 24.4%, and for patients at age 80 is 19.5% and 54.4%. The mortality rates were similar when evaluated across different cardiac ejection fractions.[5][10][14]

The prognosis is worse for those with heart failure who are hospitalized; those with heart failure commonly require repeat hospitalizations and develop an intolerance for standard treatments as the disease progresses. Data from the United States Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized during 2006 showed 30-day and 1-year mortality rates postadmission of 10.8% and 30.7,% respectively. Mortality outcomes at 1 year also demonstrate a clear relationship with age and increase from 22% for those aged 65 to 42.7% for patients aged 85 and older.[5][10]

Complications

Potential Complications of Heart Failure

- Worsening clinical status despite aggressive therapy

- Associated renal impairment and organ dysfunction can compromise heart failure treatment efforts

- Recurrent hospitalizations for heart failure or, most commonly, associated co-morbidities, with resultant financial and personal costs to patients and families

- The progressive loss of ability to carry out activities of daily life

- Increased morbidity and mortality from the date of the patient's initial diagnosis of heart failure [1][5]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Effective treatment of comorbidities and risk factor reduction can decrease the chance of developing heart failure. Patient education should be focused on ensuring compliance with prescribed evidence-based treatments.

- Hypertension: Effective treatment of systolic and diastolic hypertension can reduce the risk of heart failure by approximately 50%

- Diabetes: This condition is directly associated with the development of heart failure, independent of other associated clinical conditions.

- Alcohol: Heavy alcohol use is associated with heart failure.

- Metabolic syndromes: Following treatments based on evidence-based guidelines to decrease the risk of heart failure (ie, lipid disorders) is vital.

- Patient education: Education regarding dietary salt restriction and fluid restriction is imperative.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Treating heart failure and acute decompensated heart failure is challenging despite the use of maximal evidence-based therapy based on the stage of heart failure. Given the limited effect of current treatment strategies on the progression of heart failure, it is important to identify ways to maximize patient outcomes and quality of care by the interprofessional team. Patients at potential risk for heart failure based on comorbidities or other identified risk factors should receive appropriate evidence-based preventative counseling and treatments. When applicable, the primary care clinician who may be the most involved in managing the patient's risk factors should consult other specialists, including cardiologists, endocrinologists, pharmacists, cardiology nurses, and nutritionists, to ensure they provide the best advice and treatment for their patients. Nurses monitor patients, provide education, and collaborate with clinicians and the healthcare team to improve outcomes. Pharmacists review medications, inform patients and their families about potential adverse events, and monitor compliance. Given the propensity of patients with heart failure to require recurrent admissions, often because of non heart failure-related conditions, the collaboration between inpatient and outpatient services can be of benefit in the continuity of care and help promote improved outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gedela M, Khan M, Jonsson O. Heart Failure. South Dakota medicine : the journal of the South Dakota State Medical Association. 2015 Sep:68(9):403-5, 407-9 [PubMed PMID: 26489162]

Hsiao R, Greenberg B. Contemporary Treatment of Acute Heart Failure. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2016 Jan-Feb:58(4):367-78. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.12.005. Epub 2016 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 26764279]

Kurmani S, Squire I. Acute Heart Failure: Definition, Classification and Epidemiology. Current heart failure reports. 2017 Oct:14(5):385-392. doi: 10.1007/s11897-017-0351-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28785969]

Rimoldi SF, Yuzefpolskaya M, Allemann Y, Messerli F. Flash pulmonary edema. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2009 Nov-Dec:52(3):249-59. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.10.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19917337]

Dharmarajan K, Rich MW. Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Prognosis of Heart Failure in Older Adults. Heart failure clinics. 2017 Jul:13(3):417-426. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2017.02.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28602363]

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Oct 15:128(16):1810-52. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. Epub 2013 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 23741057]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStoltzfus S. The role of noninvasive ventilation: CPAP and BiPAP in the treatment of congestive heart failure. Dimensions of critical care nursing : DCCN. 2006 Mar-Apr:25(2):66-70 [PubMed PMID: 16552275]

Bello G, De Santis P, Antonelli M. Non-invasive ventilation in cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Annals of translational medicine. 2018 Sep:6(18):355. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.04.39. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30370282]

Yu JJ, Sunderland Y. Outcomes of hospital in the home treatment of acute decompensated congestive cardiac failure compared to traditional in-hospital treatment in older patients. Australasian journal on ageing. 2020 Mar:39(1):e77-e85. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12697. Epub 2019 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 31325230]

Habal MV, Garan AR. Long-term management of end-stage heart failure. Best practice & research. Clinical anaesthesiology. 2017 Jun:31(2):153-166. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.07.003. Epub 2017 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 29110789]

Caraballo C, Jaimes F. Organ Dysfunction in Sepsis: An Ominous Trajectory From Infection To Death. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 2019 Dec:92(4):629-640 [PubMed PMID: 31866778]

Prasad Hrishi A, Ruby Lionel K, Prathapadas U. Head Rules Over the Heart: Cardiac Manifestations of Cerebral Disorders. Indian journal of critical care medicine : peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2019 Jul:23(7):329-335. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23208. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31406441]

Dzikowska-Diduch O, Kostrubiec M, Kurnicka K, Lichodziejewska B, Pacho S, Miroszewska A, Bródka K, Skowrońska M, Łabyk A, Roik M, Gołębiowski M, Pruszczyk P. "The post-pulmonary syndrome - results of echocardiographic driven follow up after acute pulmonary embolism". Thrombosis research. 2020 Feb:186():30-35. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.12.008. Epub 2019 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 31862573]

McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA. Heart failure. Lancet (London, England). 2005 May 28-Jun 3:365(9474):1877-89 [PubMed PMID: 15924986]