Introduction

Although transesophageal ultrasound was first reported in the 1970s, the advent of phased array transducers and flexible transesophageal probes in the early 1980s enabled improved visualization of cardiac structures.[1] Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has become a commonly used imaging modality in a wide range of settings including the cardiac operating theatre, the intensive care unit, the interventional suit, as an outpatient procedure, and as a monitoring or rescue device in patients who have or are expected to have unexplained cardiovascular instability. TEE is able to provide excellent ultrasonic imaging compared to transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) because of the proximal location of the esophagus next to the heart and great vessels, and avoidance of the lungs and ribs as impediments to imaging. In addition, TEE is more practical than TTE during most surgeries and especially during cardiac surgical operations because of the need to avoid the sterile operating field.[2][3] For these reasons, TEE is superior to TEE during cardiac surgery, for certain diagnosis, and for many catheter-based cardiovascular interventions. Recently, the development and widespread availability of real-time 3-dimensional echocardiography has expanded the role of TEE in the guidance of complicated cardiac surgical procedures and catheter-based cardiac interventions such as transcatheter aortic valve replacements (TAVR).[4]

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) published a first set of guidelines for the performance of a comprehensive intraoperative TEE exam in 1999. The aim of these guidelines was to define a standard examination for the purposes of training, consistency, storage, and quality. These guidelines contain a set of twenty TEE views that were primarily designed for intraoperative use although they have been widely adopted outside of the operating room.[5] These guidelines were updated in 2013 to now include an expanded 28 standard views as well as 3-dimensional imaging.[6][6] In addition, a set of basic perioperative TEE guidelines were also published in 2013 that included 11 standard views. The SCA and the ASE realized that the availability and use of TEE as a monitoring and diagnostic rescue tool outside of cardiac surgery had dramatically increased. Therefore, a basic set of guidelines that were intended for use in general operating rooms by non-cardiac anesthesiologists were developed.[7]

Many practicing physicians that utilize TEE become certified in its use by the National Board of Echocardiography. This requires passing a test and the completion of several other requirements including a certain number of personally performed TEE exams.[7][6]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomical Views

The transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probe is inserted through the oropharynx into the esophagus. All of the described TEE views are obtained when the TEE probe is located in the esophagus or stomach. The echocardiographer is typically able to identify a variety of structures including the cardiac chambers, valves, lungs, liver, superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, hepatic vein, pulmonary veins, pulmonary arteries, aorta, and stomach. One limitation of TEE is that the left main bronchus disrupts the views of the aortic arch and proximal ascending aorta.

The 2013 Basic Perioperative Transesophageal Echocardiography Examination guidelines list the 11 most relevant views for a basic echocardiographer. These include:

- Mid-Esophageal (ME) Four-Chamber View

- ME 2-Chamber View

- ME Long-Axis (LAX) View

- ME Ascending Aortic LAX View

- ME Ascending Aortic short-axis (SAX) View

- ME AV SAX View

- ME RV Inflow-Outflow View

- ME Bicaval View

- Transgastric (TG) Midpapillary SAX View

- Descending Aortic SAX View

- Descending Aortic LAX View[7]

The updated 2013 Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transesophageal Echocardiographic Examination include 28 views. These include:

- ME Five-Chamber View

- ME Four-Chamber View

- ME Mitral Commissural View

- ME 2-Chamber View

- ME LAX View

- ME AV LAX View

- ME Ascending Aorta LAX View

- ME Ascending Aorta SAX View

- ME Right Pulmonary Vein View

- ME AV SAX View

- ME RV Inflow-Outflow View

- ME Modified Bicaval TV View

- ME Bicaval View

- ME Right and Left Pulmonary Vein View

- ME LA Appendage View

- TG Basal SAX View

- TG Midpapillary SAX View

- TG Apical SAX View

- TG RV Basal View

- TG RV Inflow-Outflow View

- Deep TG Five-Chamber View

- TG 2-Chamber View

- TG RV Inflow View

- TG LAX View

- Descending Aorta SAX view

- Descending Aorta LAX view

- UE Aortic Arch to LAX View

- UE Aortic Arch SAX View[6]

In addition, there are guidelines for the performance of an intraoperative 3-dimensional TEE exam.[8]

Indications

There are multiple clinical indications for TEE. It typically provides superior imaging versus transthoracic echocardiography. It is an invasive test, however, and its use in patients should be warranted. Indications for TEE include:

- Evaluation of acute aortic pathology (dissection, transection)

- Evaluation of prosthetic heart valves

- Evaluation of paravalvular abscess

- Evaluation of patients where TTE imaging is inadequate and the information obtained would change management

- All open heart valvular and thoracic aortic surgical procedures

- Coronary artery bypass surgeries (CABG): Its use should be considered to confirm the preoperative diagnosis, detect new pathology, to adjust the surgical plan, or to assess surgical intervention

- Catheter-based cardiac procedures (i.e., TAVR, left atrial appendage device implantation, or atrial septal defect closure)

- Non-cardiac surgery where known or suspected cardiovascular disease may result in hemodynamic compromise

- The unexplained life-threatening circulatory instability that is not corrected by usual therapy (rescue TEE)

- Diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism

- Confirmation and diagnosis of air embolism, particularly in neurosurgical procedures

- Evaluation of pericardial effusion

- Evaluation of congenital cardiac disease in the intraoperative period[6][9]

Contraindications

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is considered to be a relatively safe procedure when performed by a trained physician. There is disagreement in the literature and among experts in the field about the presence of absolute and relative contraindications to the use of transesophageal echocardiography. However, many practitioners agree that the following conditions are

Absolute

- Perforated viscous

- Esophageal pathology including stricture, trauma, tumor, scleroderma, Mallory-Weiss tear, diverticulum

- Active upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Recent upper gastrointestinal surgery

- Previous esophagectomy or esophagogastrectomy

- Unrepaired tracheoesophageal fistula

- Poor airway control

- Severe respiratory depression

- Uncooperative, unsedated patient

Relative

- Atlantoaxial joint disease

- Severe cervical arthritis

- Prior radiation to the chest

- Symptomatic hiatal hernia

- Recent upper gastrointestinal bleed

- Presence of esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease

- Thoracoabdominal aneurysm

- Barrett's esophagus

- History of dysphagia

- Coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia

- History of esophageal or gastric surgery

- History of esophageal cancer Esophageal varices or diverticulum

- Vascular ring, aortic arch anomaly with or without airway compromise

- Oropharyngeal pathology

- Post-gastrostomy or fundoplication limit imaging to esophageal windows

According to the 2010 American Society of Anesthesiologists and Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Perioperative Transesophageal Echocardiography, TEE may be utilized in patients with oral, esophageal, or gastric conditions if the expected benefit is greater than the potential risk and if the necessary precautions are followed. These include limiting the exam or its duration, the avoidance of unnecessary probe manipulations, having the exam performed by the most experienced echocardiographer, acquiring a gastroenterology consult, and the consideration of other imaging options such as TTE or epicardial echocardiography.[6][9]

Equipment

Knowledge and understanding of ultrasound physics and familiarity with the echocardiography machine and its controls are paramount to obtain useful TEE imaging, decrease artifacts, and to prevent misdiagnosis. Equipment required for a transesophageal echocardiography exam includes both an echocardiography machine and an appropriate transducer, as well as a method to archive and store, completed examinations. The multiplane (meaning that its imaging angle can be adjusted from zero to one-hundred eighty degrees) TEE probe has a connector that can be attached to the ultrasound machine, 2 dials that control side-to-side and forward and backward movement of the tip, and an ultrasonic transducer at the end. The transducer contains ceramic lead zirconate titanate and consists of a phased array of piezoelectric crystals which both send and receive ultrasound waves. The transducer and probe may be 2-dimensional or 3-dimensional and contain a dramatically increased number of crystals. During an exam, the transducer will lie in contact with the esophagus or stomach and generate sound waves which will be attenuated, refracted, scattered, or reflected back from certain cardiac structures. In echocardiography, ultrasound with frequencies of 2 to 10 MHz is utilized. This is significantly higher than sound in the audible range (the upper limit of which is approximately 20,000 Hz). The piezoelectric crystals will then convert the reflected sound into electric pulses which allow the creation of an image of the heart or other structure on display.[6][10]

One end of the TEE probe is a connector that is plugged and locked into the echocardiography machine. The handle of the probe has two control wheels and image array rotation buttons. The wheels control the side-to-side and front-to-back movement of the articulating end of the probe. The handle also contains a lock which allows the user to lock the probe in a certain configuration that is initially set by the control wheels. In addition to the movement controlled by the wheels, the probe can be inserted or withdrawn and can be twisted to the left or right. The buttons allow the piezoelectric crystals to be rotated clockwise or counterclockwise from zero to one-hundred eighty degrees. Adult TEE probes are very similar but larger than a standard gastroscope. Pediatric TEE probes are a considerably smaller diameter, higher frequency, and have more flexibility in the shaft.[11]

The keyboard and control panel of the echocardiography machine contains a plethora of options for adjustment and acquisition of the probe, display, and acquisition of the image. Some of these include a system gain setting, time gain compensation, compression, image depth and width, B-mode, color Doppler, pulse wave Doppler, continuous wave Doppler, power output, image freeze, and image store or acquire.[6]

Personnel

Although transesophageal echocardiography is a relatively safe modality, it is an invasive procedure and does carry the risk of infrequent but potentially life-threatening complications. Therefore, it should only be performed by qualified, trained physicians. There are multiple, recently published guidelines that cover the training and maintenance of certification guidelines for the practice of intraoperative echocardiography. Cardiologists often have a base of knowledge in transthoracic echocardiography before learning transesophageal echocardiography. This is not always the case for anesthesiologists, who utilize intraoperative TEE at a much higher rate than TTE. The majority of the intraoperative echocardiography guidelines are synthesized and published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), the Society for Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA), and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE). Physicians typically demonstrate their competence in echocardiography by completion of a training program and achieving a passing score on a certifying exam. The primary examination and certification organization for intraoperative echocardiography is the National Board of Echocardiography (NBE) which was founded in 1998 by a joint partnership between the SCA and the ASE.[6]

The NBE offers examinations and certifications in the following areas:

- The ASCeXAM is for physicians who can show special competence in all areas of echocardiography including TTE, TEE, and stress echocardiography - this exam and certification is most commonly taken and acquired by cardiologists

- The Advanced PTEeXAM is intended for physicians who are especially competent in advanced perioperative transesophageal echocardiography - this is the exam and certification which is most commonly acquired by cardiovascular anesthesiologists; the goal of this exam is to demonstrate the full diagnostic and surgical decision-making capacity of perioperative TEE

- The Basic PTEeXAM covers basic perioperative transesophageal echocardiography: The goal of this exam and certification is the process of intraoperative non-diagnostic monitoring except in the case of an emergent situation; this exam and certification is most commonly obtained by general anesthesiologists and is not specifically designed for those who routinely practice cardiovascular anesthesiology

In order to acquire certification in any of the above areas, the physician applicant must not only pass a computerized exam, he or she must also complete a variety of additional requirements including personally performing a certain number of applicable echocardiography examinations, completion of a certified training program, acquisition of a certain number of continuing medical education requirements, and the achievement of board certification in their specialty.[6][12]

Preparation

Detailed history and physical examination should be done prior to the procedure to rule out contraindications for the procedure. Patient should be thoroughly assessed for suitability for moderate sedation. The history and physical examination should focus on identifying risk factors that may increase susceptibility to sedatives and analgesics, such as cardiopulmonary diseases, renal and hepatic impairment that can slow down drug metabolism, history of allergic reactions or problems with airway in the past during anesthesia, snoring or sleep apnea.

Technique or Treatment

After pre procedure clearance, probe is inserted via mouth under moderate sedation. Patient's vitals should be monitored continuously during the procedure. The probe is inserted and is manipulated to obtain different views of the heart. The following terminology is used in the ASE/SCA guidelines to understand the manipulation of the probe with the assumption that the imaging plane is anterior to the esophagus looking into the heart in a patient in supine anatomic position.[6]

Rotating the anterior aspect of the probe within the esophagus clockwise is called “turning to the right” and rotating it counterclockwise is called “turning to the left”. “Advancing the transducer” means pushing the tip of the probe more distal into the esophagus or the stomach while pulling the tip more proximally is called “withdrawing the probe”. Flexing the tip of the probe with the large control wheel anteriorly is called “anteflexing”, and flexing it posteriorly “retroflexing”. Using the small control wheel, flexing the tip of the probe to the patient's right is called “flexing to the right”, and flexing it to the left is called “flexing to the left”. Finally, increasing the transducer multiplane angle from zero degrees towards 180 degrees is called “rotating or multiplane forward”, and decreasing in the opposite direction towards zero degrees is called “rotating or multiplane back”.

Complications

Although transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has the reputation of a safe imaging modality, it does carry the risk of complications that range from mild to potentially life-threatening. The physical insertion and manipulation of the TEE probe in the intraoperative setting can cause a variety of gastric, esophageal, and oropharyngeal complications. According to several large studies, the overall rate of TEE related complications ranged from 0.2% to 1.4%. Intraoperative TEE does carry slightly different risks in comparison to TEEs performed in the ambulatory setting because patient's that undergo TEE in the operating room (OR) are typically under general anesthesia and have received neuromuscular blocking agents. These patients are unable to swallow and potentially protest dangerous probe manipulations. In addition, the TEE probe is often kept inserted for a prolonged period in the operating room, particularly in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Despite these challenges, the rate of TEE related compilations appears to be similar in the ambulatory and operating room settings. Many of the gastrointestinal injuries related to TEE may not present until after the first twenty-four hours and may have previously led experts to underestimate the overall risk of TEE related complications.

TEE related injuries include:

- Laceration of lip

- Loose or chipped tooth

- Tongue ulceration

- Laceration of the oropharynx

- Dysphagia

- Odynophagia

- Pharyngeal edema

- Vocal cord palsy or paralysis

- Gastritis

- Stomach ulceration

- Esophagitis

- Esophageal perforation

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Dysrhythmias

- Compression of the mediastinal structures

- Inadvertent extubation[6][13][9]

Clinical Significance

In summary, transesophageal echocardiography has seen a dramatic increase in usage over the past decade, from cardiac surgery to its use as a monitoring or rescue device in high-risk patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. The widespread availability of echocardiography machines and the increased number of physicians with training in their use has led to this increased usage.

The clinical benefits of intraoperative TEE are of two types, those that impact hemodynamic/airway management and those that result in changes in the surgical procedure. Multiple groups have reported that intraoperative TEE for both cardiac and non-cardiac surgery detects unrecognized conditions such as hypovolemia, wall motion abnormalities and right ventricular failure. In these cases, use of TEE helps guide appropriate administration of volume, vasopressors, inotropes and inodilators. TEE has also resulted in changes in surgical procedures. It is often used to assess quality of valve repair or replacement and, if judged to be inadequate, the patient will be placed back on cardiopulmonary bypass for revision or conversion from perhaps valve repair to valve replacement. TEE has also demonstrated deterioration of wall motion post-cardiopulmonary bypass, indicating air that needs to be vented from a bypass graft, or a more serious problem that requires further surgical revision of a graft. Mild desaturation may be explained by detection of a patent foramen ovale, which can be managed by appropriate adjustment of systemic vascular resistance. A previously unrecognized large patent foramen ovale, atrial or ventricular septal defect, or clot in the left atrial appendage, have all resulted in modification of the surgical plan. Finally, severe hemodynamic instability has sometimes been explained by visualization of thrombi in the right side of the heart or pulmonary artery. In other cases, thrombi have not been visualized, but signs of right-sided heart failure, consistent with pulmonary embolism, have led to further studies that confirmed the presence of pulmonary emboli. Treatment of such patients has included thrombolysis and, when appropriate, surgical embolectomy.

There is strong evidence to support the use of TEE in non-cardiac surgery both for monitoring and as a diagnostic rescue device when unexplained life-threatening circulatory instability persists despite attempts at correction. In addition, TEE is frequently used in surgical procedures where the patient has severe cardiovascular comorbidities which may lead to significant hemodynamic, pulmonary, or neurologic instability during the case.[14][15]

With the increased attention given to ultrasound education during medical training and the increased availability of echocardiographic equipment, the use of echocardiography will most certainly increase in the future.[4]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although transesophageal echocardiography is a relatively safe modality, it is an invasive procedure and does carry the risk of infrequent but potentially life-threatening complications. Therefore, it should only be performed by qualified, trained physicians. Cardiologists, anesthesiologists and critical care physicians who demonstrate their competence in echocardiography by completion of a training program and achieving a passing score on a certifying exam, can safely perform the procedure. Improving health professional understanding of how to utilize TEE to evaluate and treat patients can lead to better patient outcomes.

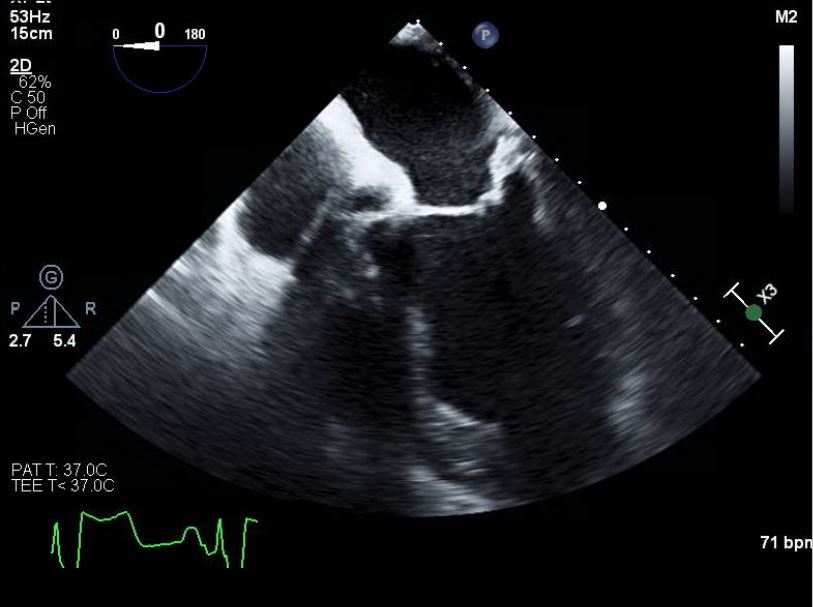

Media

References

Chandhok D, Perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. Missouri medicine. 2005 Sep-Oct; [PubMed PMID: 16259398]

Kratz T,Campo Dell'Orto M,Exner M,Timmesfeld N,Zoremba M,Wulf H,Steinfeldt T, Focused intraoperative transthoracic echocardiography by anesthesiologists: a feasibility study. Minerva anestesiologica. 2015 May; [PubMed PMID: 25220551]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKratz T,Holz S,Steinfeldt T,Exner M,Campo dell'Orto M,Kratz C,Wulf H,Zoremba M, Feasibility and Impact of Focused Intraoperative Transthoracic Echocardiography on Management in Thoracic Surgery Patients: An Observational Study. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2018 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 29217238]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMahmood F,Shernan SK, Perioperative transoesophageal echocardiography: current status and future directions. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2016 Aug 1; [PubMed PMID: 27048769]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShanewise JS,Cheung AT,Aronson S,Stewart WJ,Weiss RL,Mark JB,Savage RM,Sears-Rogan P,Mathew JP,Quiñones MA,Cahalan MK,Savino JS, ASE/SCA guidelines for performing a comprehensive intraoperative multiplane transesophageal echocardiography examination: recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography Council for Intraoperative Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force for Certification in Perioperative Transesophageal Echocardiography. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1999 Oct [PubMed PMID: 10512257]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHahn RT,Abraham T,Adams MS,Bruce CJ,Glas KE,Lang RM,Reeves ST,Shanewise JS,Siu SC,Stewart W,Picard MH, Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2013 Sep [PubMed PMID: 23998692]

Reeves ST,Finley AC,Skubas NJ,Swaminathan M,Whitley WS,Glas KE,Hahn RT,Shanewise JS,Adams MS,Shernan SK, Basic perioperative transesophageal echocardiography examination: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2013 May [PubMed PMID: 23622926]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLang RM,Badano LP,Tsang W,Adams DH,Agricola E,Buck T,Faletra FF,Franke A,Hung J,de Isla LP,Kamp O,Kasprzak JD,Lancellotti P,Marwick TH,McCulloch ML,Monaghan MJ,Nihoyannopoulos P,Pandian NG,Pellikka PA,Pepi M,Roberson DA,Shernan SK,Shirali GS,Sugeng L,Ten Cate FJ,Vannan MA,Zamorano JL,Zoghbi WA, EAE/ASE recommendations for image acquisition and display using three-dimensional echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2012 Jan [PubMed PMID: 22183020]

Hauser ND,Swanevelder J, Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE): contra-indications, complications and safety of perioperative TOE Echo research and practice. 2018 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 30303686]

Lawrence JP, Physics and instrumentation of ultrasound. Critical care medicine. 2007 Aug [PubMed PMID: 17667455]

Wang L,Zhang J,Zheng SP,He L,Wang J,Wang XF,Xie MX, Research and application of transnasal transesophageal echocardiography probe. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Medical sciences = Hua zhong ke ji da xue xue bao. Yi xue Ying De wen ban = Huazhong keji daxue xuebao. Yixue Yingdewen ban. 2017 Oct [PubMed PMID: 29058296]

Capdeville M,Ural KG,Patel PA,Broussard DM,Goldhammer JE,Linganna RE,Feinman JW,Gordon EK,Augoustides JGT, The Educational Evolution of Fellowship Training in Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology - Perspectives From Program Directors Around the United States. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2018 Apr [PubMed PMID: 29276092]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDesjardins G,Cahalan M, The impact of routine trans-oesophageal echocardiography (TOE) in cardiac surgery. Best practice & research. Clinical anaesthesiology. 2009 Sep [PubMed PMID: 19862886]

Fayad A,Shillcutt SK, Perioperative transesophageal echocardiography for non-cardiac surgery. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2018 Apr [PubMed PMID: 29150779]

Staudt GE,Shelton K, Development of a Rescue Echocardiography Protocol for Noncardiac Surgery Patients. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2018 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 29916865]