Introduction

Morgagni hernia was first identified in 1761 by Giovanni Battista Morgagni, the founder of pathological anatomy. Anatomically, the diaphragm is a thin, dome-shaped, musculotendinous structure that separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Morgagni hernia is the rarest form of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), accounting for only 2% to 5% of cases. Diaphragmatic hernias include the Bochdalek, hiatal, and paraesophageal hernias. A Bochdalek hernia occurs due to a defect in the diaphragm's posterolateral region. A hiatal hernia has a defect at the esophageal hiatus; a paraesophageal hernia has a defect adjacent to the esophageal hiatus.[1] A Morgagni hernia arises from an anterior, retrosternal diaphragmatic defect.[2] The condition is rarer than the other CDH types.[3][4][5] Morgagni hernias tend to be less symptomatic as pulmonary hypoplasia is uncommon, leading to a delayed diagnosis of these defects.[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Morgagni hernias discovered during infancy or early childhood are often associated with other congenital anomalies, with the incidence ranging from 34% to 50%.[7][8] The most common anomalies include cardiac defects (25-60%) and trisomy 21 (15%-71%). Malrotation, anorectal malformations, omphalocele, skeletal anomalies, and pentalogy of Cantrell have also been associated with a Morgagni hernia. Defective dorsoventral migration of rhabdomyoblasts, linked to increased cellular adhesiveness in patients with trisomy 21, may explain the higher recurrence rate of hernia repair in individuals with Down syndrome.[9]

In contrast to patients with a Bochdalek hernia, who usually become symptomatic soon after birth due to pulmonary hypoplasia, up to 50% of patients with Morgagni hernias are asymptomatic upon diagnosis.[10] Patients younger than age 2 are more likely to be symptomatic at the time of diagnosis.[11][12] However, the diagnosis may not be made until adulthood, when chest imaging is performed for unrelated reasons. Due to pericardial attachments supporting the left side of the diaphragm, up to 91% of Morgagni hernias are found on the right side, 5% are on the left side, and 4% are bilateral.[13]

Epidemiology

The estimated incidence of Morgagni hernias is between 1 in 2000 and 1 in 5000 live births. However, the true incidence of this condition is unknown. Morgagni hernias comprise 2% to 5% of all CDH cases.

Pathophysiology

The central tendinous portion of the diaphragm, formed by the septum transversum (a mesodermal sheet), plays a key role in separating the thoracic from the abdominal cavity. The diaphragm is anchored anteriorly by small muscle bundles attached to the sternal part of the xiphoid process and is further supported by attachments along its costal and lumbar regions. A Morgagni hernia arises from a defect at the junction where the diaphragm's septum transversum and costal elements meet, allowing abdominal contents to herniate into the thoracic cavity. A Morgagni hernia is located posterolaterally to the sternum and is caused by a failure of the pars tendinalis part of the costochondral arches to fuse with the pars sternalis.[14] Failure of fusion on the right side gives rise to a Morgagni hernia, while a failure on the left is often called a Larrey hernia.

Although left-sided and bilateral hernias occur, 90% of Morgagni hernias occur on the right side due to the pericardial attachments to the diaphragm that provide protection and support to the left side. The defects are initially small, and over 90% of defects have a hernia sac. The defects can grow over time due to increased intraabdominal pressure, causing diaphragm weakness.[15] The hernia most often contains a portion of the large intestine (54% to 72%) or omentum (65%) but may also have parts of the small intestine, stomach, and liver.[16][17]

History and Physical

A Morgagni hernia usually presents later in life than a Bochdalek hernia, with patients reporting respiratory and upper gastrointestinal symptoms as their main complaint. However, up to 50% of patients may be asymptomatic on presentation, with diagnosis occurring during the workup for an unrelated problem.[18] Respiratory manifestations, such as respiratory distress or tachypnea (20%-73%) and recurrent pulmonary infections (29%-55%), are most common in children. However, poor feeding, failure to thrive, and coughing and choking with feeds may also be seen.[19][20][21]

Likewise, adults may experience gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms, including retrosternal or chest pain often relieved by standing, dyspnea, flatulence, indigestion, or cramping. Trauma, obesity, pregnancy, chronic constipation, or chronic cough may precipitate the onset of symptoms by increasing intraabdominal pressure, causing herniation of the omentum and intestine into the defect. The physical exam may reveal bowel sounds on chest auscultation if the intestine is present in the hernia.[22] One must also be aware of acute strangulation or volvulus, as evidenced by rebound tenderness, tachycardia, persistent vomiting, and blood on the rectal exam.[23] These patients require prompt resuscitation, diagnosis, evaluation of the bowel with possible bowel resection, and repair of the hernia defect.[24]

Evaluation

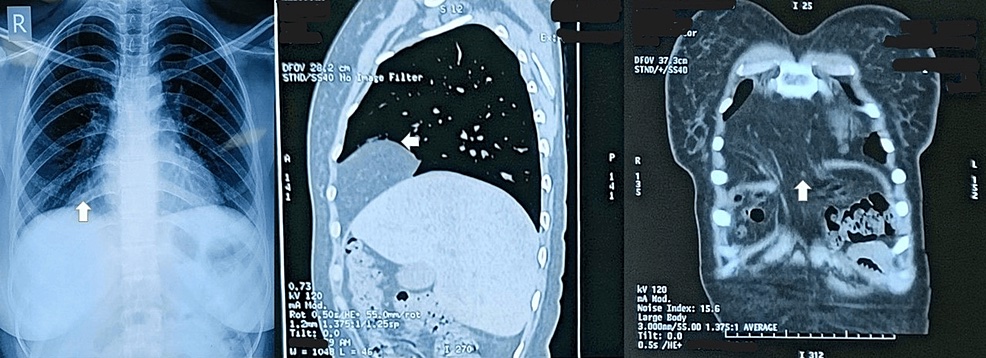

The definitive diagnosis is made radiologically, particularly with anteroposterior and lateral chest radiographs. With bowel herniation, a radiolucent paracardiac shadow is seen on the anteroposterior view that is retrosternal on lateral radiographs. Chest radiographs alone can make the diagnosis approximately 71% of the time, usually when the bowel is seen in the chest. A rounded opacity is usually found at the right cardiophrenic angle when the omentum or solid organs herniate through the defect.

Further imaging, such as a chest computed tomography (CT) scan, swallow study, or barium enema, may be used to confirm the diagnosis. A CT scan is often the next step in the evaluation, as it is easy to obtain and has up to a 100% rate of correctly identifying the defect. The CT scan typically shows a retrosternal fat density mass when omentum is included or an air-containing viscus if the bowel has herniated through the defect. A swallow study may be performed if a hiatal hernia is part of the differential diagnosis. A barium enema has also been employed, where an upward angulation of the midtransverse colon can identify a herniated colon into the defect (see Image. Morgagni Hernia on Radiography).

Treatment / Management

Current recommendations for the initial ventilator settings in managing CDH include the following:

- Peak inspiratory pressure less than 25 cm H2O

- Positive end-expiratory pressure 3 to 5 cm H2O

- 40 to 60 breaths/min rate to maintain the partial pressure of CO2 between 50 and 70 mm Hg [25]

Repair is recommended for all Morgagni hernias due to the risk of incarceration. However, the repair approach and type are still under debate.[26] The hernia defect may be approached either through an abdominal or thoracic incision. A posterolateral right thoracotomy is made through the 6 intercostal spaces when utilizing the thoracic approach. The advantages of this technique are a more accurate vision of the right-sided defect, easier dissection of the hernia sac off the pericardium, mediastinal, and pleural structures, and a potentially safer reduction of abdominal viscerae such as the liver. The hernia sac may or may not be excised. Afterward, 0-silk or 0-polypropylene sutures are used to close the defect. The thoracic approach has several disadvantages, including the risk of missing a bilateral defect due to limited visibility, a higher chance of requiring postoperative ventilation based on preoperative respiratory status, and the risk of chest wall deformity in children if performed before significant growth.

Meanwhile, the abdominal approach may be performed either through an open laparotomy incision or with minimally invasive laparoscopic techniques. The advantages of the abdominal technique include the ability to identify and repair bilateral defects and evaluate and repair other intraabdominal pathology, such as malrotation, during the same operation. Open laparotomy is typically reserved for patients who require an emergency repair, cannot tolerate laparoscopy, have severe scoliosis or extensive adhesions, or warrant extensive bowel resection or retrieval from an incarcerated hernia.

An upper abdominal incision is performed, and the hernia contents are reduced. Some debate exists about whether the hernia sac should be excised or incorporated into the sutures. However, primary repairs should be under minimal tension. Nasr recommends placing a mesh for hernias larger than 20 to 30 cm. The defect is repaired with nonabsorbable sutures in a mattress fashion, incorporating the costal margins. Open laparotomy has been shown to have shorter operating times than laparoscopy. Still, the minimally invasive approach confers a shorter recovery time and faster return to normal activities and eating, with no difference in complication rates while providing more space for dissection and better visualization.[27](B2)

Georgacopulo was the first to report a successful laparoscopic Morgagni hernia in a child in 1997.[28] With the laparoscopic approach, the patient is placed in reverse Trendelenburg with the surgeon located at the foot of the bed.[29] The camera port is placed through the umbilicus, and 2 working ports are positioned in the right and left upper abdomen in the midclavicular line.[30] Depending on the defect's size, the falciform ligament may need to be divided for adequate exposure. The hernia contents are reduced, with the sac excised at this time if required. The defect often has a greater transverse than anteroposterior diameter, so closure with sutures brought through the abdominal wall may be used.[31](B2)

Patch placement in large defects occurs first by suturing the patch to the posterior rim of the hernia defect. The patch is then incorporated with nonabsorbable sutures that travel full-thickness through the anterior abdominal wall and are tied in the subcutaneous tissue. For defects that do not require a patch, closure is performed using U-type stitches that pass through the abdominal wall (including the hernia sac if present), incorporate the posterior rim of the diaphragmatic defect, and exit through the abdominal wall, secured in the subcutaneous tissue. This type of repair is beneficial in the absence of an anterior diaphragmatic rim and is easier to perform than intracorporeal sutures. Recovery is usually uneventful, with most patients discharged within 3 days of surgery. The robotic technique has also been described, with improved ergonomics, articulation, and tremor filtration cited as benefits of this minimally invasive version.[32](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis may include a pericardial cyst, loculated pneumothorax, or hiatal hernia if a bowel loop is seen herniating through a diaphragmatic defect on chest radiography. A herniated part of the omentum or liver may be visualized as a solid structure on chest x-rays. However, this radiologic finding may also be present in atelectasis, pneumonia, pericardial fat pad, intrathoracic lipoma, bronchial carcinoma, pleural mesothelioma, or an atypical mediastinal tumor. Further imaging with a lateral chest radiograph or CT scan can confirm the Morgagni defect.[33]

Prognosis

For defects found in infancy, the risk factors for mortality from a Morgagni hernia are often prematurity-associated, such as low birth weight, early gestational age, and low APGAR (appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration) scores. The presence of other congenital anomalies also increases this risk. Although pulmonary hypoplasia is not commonly seen in Morgagni hernias, factors that can impact outcomes include prenatal identification and the defect's size, especially if a sac is included. However, the condition's lifelong implications for children are unknown. After repair, most patients recover well with a resolution of preoperative symptoms and a low recurrence rate.

Complications

Nonhiatal transdiaphragmatic hernias in adults, whether congenital or posttraumatic, are rare conditions that need to be differentiated from paraesophageal hernias. According to specialized literature, these hernias often present as unexpected diagnoses. A combination of digestive symptoms with respiratory or cardiac issues may suggest the presence of a congenital or posttraumatic hernia.[34] Even asymptomatic should be referred for surgical correction due to concerns for bowel obstruction, strangulation, volvulus, and necrosis, which can occur in up to 10% of cases. Potential postsurgical complications include wound infections, incisional or port site hernias, stitch abscesses, and bowel obstruction.

Recurrence rates range from 2% to 42%, though many studies report no recurrences even after 10 years of follow-up. Risk factors for recurrence include closing the defect under tension without using a patch, leaving the sac in place without resection, use of absorbable sutures for repair, and a patient history of Down syndrome. Repair techniques vary, each with unique pitfalls. The transthoracic approach risks missing bilateral defects, is suboptimal for sac removal, may require postoperative ventilation, and can potentially cause chest wall deformity in children. Open laparotomy, ideal for complicated or emergent cases, has longer recovery, higher wound complication rates, and worse cosmesis than minimally invasive methods. All approaches yield good outcomes if their benefits and risks are well understood.

Deterrence and Patient Education

A Morgagni hernia is a rare CDH type. The condition is a possible diagnosis in the presence of recurrent pulmonary infections, shortness of breath, or worsening abdominal pain or vomiting. Patients with such manifestations should seek healthcare attention, as the defect typically requires surgery through the chest or abdomen. A synthetic patch may need to be placed if the defect is large. The postsurgical recurrence rate is low, and most patients experience full symptomatic relief.

Pearls and Other Issues

Symptomatic individuals with a Morgagni hernia may present with recurrent chest infections, intermittent gastrointestinal symptoms, persistent vomiting, tachycardia, and rebound tenderness indicative of acute strangulation. Surgical repair is indicated to prevent emergent repair of strangulated or volvulized bowel, even in patients who are asymptomatic upon diagnosis. Patients with Down syndrome have a higher risk of recurrence. Thus, Morgagni hernia should remain in the differential diagnosis if a patient returns with similar symptoms or obstruction signs.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with Morgagni hernias may present with respiratory symptoms and gastrointestinal complaints or be asymptomatic. The workup should include a chest radiograph, which may show air-containing viscus. A CT scan may be obtained to confirm the diagnosis if radiography is inconclusive. Timely referral to a general surgeon allows for semielective repair before complications, such as obstruction or intestinal perforation, occur. The prognosis is good, with a low recurrence rate. Good communication and collaboration between interprofessionals can limit complications, leading to improved outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Morgagni Hernia on Radiography. The chest radiograph (posteroanterior view) shows a nonspecific opacity at the right cardiophrenic angle (left image with white arrow). Chest computed tomography scan (middle and right images) confirms the anteromedial diaphragmatic defect with herniation of omental fat without bowel loops (white arrow).

Contributed by Kumar Sambhav, MD. Obtained with informed consent.

References

Papanikolaou V, Giakoustidis D, Margari P, Ouzounidis N, Antoniadis N, Giakoustidis A, Kardasis D, Takoudas D. Bilateral Morgagni Hernia: Primary Repair without a Mesh. Case reports in gastroenterology. 2008 Jul 9:2(2):232-7. doi: 10.1159/000142371. Epub 2008 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 21490893]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNasr A, Fecteau A. Foramen of Morgagni hernia: presentation and treatment. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2009 Nov:19(4):463-8. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2009.08.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20112628]

Simson JN, Eckstein HB. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a 20 year experience. The British journal of surgery. 1985 Sep:72(9):733-6 [PubMed PMID: 4041735]

Garriboli M, Bishay M, Kiely EM, Drake DP, Curry JI, Cross KM, Eaton S, De Coppi P, Pierro A. Recurrence rate of Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia following laparoscopic repair. Pediatric surgery international. 2013 Feb:29(2):185-9. doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3199-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23143132]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLatif Al-Arfaj A. Morgagni's hernia in infants and children. The European journal of surgery = Acta chirurgica. 1998 Apr:164(4):275-9 [PubMed PMID: 9641369]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLim L, Gilyard SM, Sydorak RM, Lau ST, Yoo EY, Shaul DB. Minimally Invasive Repair of Pediatric Morgagni Hernias Using Transfascial Sutures with Extracorporeal Knot Tying. The Permanente journal. 2019:23():. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18.208. Epub 2019 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 31926567]

Al-Salem AH. Congenital hernia of Morgagni in infants and children. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2007 Sep:42(9):1539-43 [PubMed PMID: 17848245]

Escarcega P, Riquelme MA, Lopez S, González AD, Leon VY, Garcia LR, Cabrera H, Solano H, Garcia C, Espinosa JR, Geistkemper CL, Elizondo RA. Multi-Institution Case Series of Pediatric Patients with Laparoscopic Repair of Morgagni Hernia. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2018 Aug:28(8):1019-1022. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0621. Epub 2018 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 29620946]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLamas-Pinheiro R, Pereira J, Carvalho F, Horta P, Ochoa A, Knoblich M, Henriques J, Henriques-Coelho T, Correia-Pinto J, Casella P, Estevão-Costa J. Minimally invasive repair of Morgagni hernia - A multicenter case series. Revista portuguesa de pneumologia. 2016 Sep-Oct:22(5):273-8. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2016.03.008. Epub 2016 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 27142810]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGolden J, Barry WE, Jang G, Nguyen N, Bliss D. Pediatric Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia: a descriptive study. Pediatric surgery international. 2017 Jul:33(7):771-775. doi: 10.1007/s00383-017-4078-3. Epub 2017 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 28289880]

Tan YW, Banerjee D, Cross KM, De Coppi P, GOSH team, Blackburn SC, Rees CM, Giuliani S, Curry JI, Eaton S. Morgagni hernia repair in children over two decades: Institutional experience, systematic review, and meta-analysis of 296 patients. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2018 Oct:53(10):1883-1889. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.04.009. Epub 2018 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 29776739]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJetley NK, Al-Assiri AH, Al-Helal AS, Al-Bin Ali AM. Down's syndrome as a factor in the diagnosis, management, and outcome in patients of Morgagni hernia. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2011 Apr:46(4):636-639. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.10.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21496530]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMohamed M, Al-Hillan A, Shah J, Zurkovsky E, Asif A, Hossain M. Symptomatic congenital Morgagni hernia presenting as a chest pain: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2020 Jan 18:14(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13256-019-2336-9. Epub 2020 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 31952551]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLoong TP, Kocher HM. Clinical presentation and operative repair of hernia of Morgagni. Postgraduate medical journal. 2005 Jan:81(951):41-4 [PubMed PMID: 15640427]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSambhav K, Dushyant K, Jayaswal SR. Morgagni Hernia: A Rare Presentation in a Young Adult. Cureus. 2024 Jan:16(1):e52463. doi: 10.7759/cureus.52463. Epub 2024 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 38371132]

Laituri CA, Garey CL, Ostlie DJ, Holcomb GW 3rd, St Peter SD. Morgagni hernia repair in children: comparison of laparoscopic and open results. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2011 Jan-Feb:21(1):89-91. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0174. Epub 2011 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 21214367]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYoung MC, Saddoughi SA, Aho JM, Harmsen WS, Allen MS, Blackmon SH, Cassivi SD, Nichols FC, Shen KR, Wigle DA. Comparison of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgical Management of Morgagni Hernia. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2019 Jan:107(1):257-261. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.08.021. Epub 2018 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 30296422]

Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Kim P, Mathisen DJ. Foramen of Morgagni hernia: changes in diagnosis and treatment. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2004 Jun:77(6):1956-9 [PubMed PMID: 15172245]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVaos G, Skondras C. Colonic necrosis because of strangulated recurrent Morgagni's hernia in a child with Down's syndrome. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2006 Mar:41(3):589-91 [PubMed PMID: 16516643]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKnight CG, Gidell KM, Lanning D, Lorincz A, Langenburg SE, Klein MD. Laparoscopic Morgagni hernia repair in children using robotic instruments. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2005 Oct:15(5):482-6 [PubMed PMID: 16185121]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArca MJ, Barnhart DC, Lelli JL Jr, Greenfeld J, Harmon CM, Hirschl RB, Teitelbaum DH. Early experience with minimally invasive repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias: results and lessons learned. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2003 Nov:38(11):1563-8 [PubMed PMID: 14614701]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKiliç D, Nadir A, Döner E, Kavukçu S, Akal M, Ozdemir N, Akay H, Okten I. Transthoracic approach in surgical management of Morgagni hernia. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2001 Nov:20(5):1016-9 [PubMed PMID: 11675191]

Moghissi K. Operation for repair of obstructed substernocostal (Morgagni) hernia. Thorax. 1981 May:36(5):392-4 [PubMed PMID: 7031964]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKatsaros I, Katelani S, Giannopoulos S, Machairas N, Kykalos S, Koliakos N, Kapetanakis EI, Bakopoulos A, Schizas D. Management of Morgagni's Hernia in the Adult Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. World journal of surgery. 2021 Oct:45(10):3065-3072. doi: 10.1007/s00268-021-06203-3. Epub 2021 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 34159404]

Chatterjee D, Ing RJ, Gien J. Update on Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2020 Sep:131(3):808-821. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004324. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31335403]

Hughes BD, Nakayama D. Giovanni Battista Morgagni and the Morgagni Hernia. The American surgeon. 2023 Nov:89(11):5049-5050. doi: 10.1177/00031348211011108. Epub 2021 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 33886389]

Al-Salem AH, Zamakhshary M, Al Mohaidly M, Al-Qahtani A, Abdulla MR, Naga MI. Congenital Morgagni's hernia: a national multicenter study. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2014 Apr:49(4):503-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.08.029. Epub 2013 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 24726101]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGeorgacopulo P, Franchella A, Mandrioli G, Stancanelli V, Perucci A. Morgagni-Larrey hernia correction by laparoscopic surgery. European journal of pediatric surgery : official journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery ... [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie. 1997 Aug:7(4):241-2 [PubMed PMID: 9297523]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMallick MS, Alqahtani A. Laparoscopic-assisted repair of Morgagni hernia in children. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2009 Aug:44(8):1621-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19635315]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAnderberg M, Kockum CC, Arnbjornsson E. Morgagni hernia repair in a small child using da Vinci robotic instruments--a case report. European journal of pediatric surgery : official journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery ... [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie. 2009 Apr:19(2):110-2. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038500. Epub 2008 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 18629776]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAzzie G, Maoate K, Beasley S, Retief W, Bensoussan A. A simple technique of laparoscopic full-thickness anterior abdominal wall repair of retrosternal (Morgagni) hernias. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2003 May:38(5):768-70 [PubMed PMID: 12720190]

Lorincz A, Langenburg S, Klein MD. Robotics and the pediatric surgeon. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2003 Jun:15(3):262-6 [PubMed PMID: 12806254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKeyes S, Spouge RJ, Kennedy P, Rai S, Abdellatif W, Sugrue G, Barrett SA, Khosa F, Nicolaou S, Murray N. Approach to Acute Traumatic and Nontraumatic Diaphragmatic Abnormalities. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2024 Jun:44(6):e230110. doi: 10.1148/rg.230110. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38781091]

Predescu D, Achim F, Socea B, Ceaușu MC, Constantin A. Rare Diaphragmatic Hernias in Adults-Experience of a Tertiary Center in Esophageal Surgery and Narrative Review of the Literature. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Dec 29:14(1):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14010085. Epub 2023 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 38201394]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence