Introduction

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), or intraductal carcinoma, is a non-invasive breast cancer characterized by a proliferation of abnormal epithelial cells confined within the basement membrane. Disruption of the basement membrane layer would change the diagnosis from DCIS to invasive breast cancer. DCIS is considered to be a precursor for invasive breast cancer.[1] Specifically, the World Health Organization defines the term DCIS as "a neoplastic proliferation of epithelial cells confined to the mammary ductal-lobular system and characterized by subtle to marked cytologic atypia and an inherent but not necessarily obligate tendency to progression to invasive breast cancer."[2] Although grouped, DCIS is, in reality, a heterogeneous group of lesions that varies in the clinical presentation, genetics, biomarkers, morphologic features, as well as the clinical potential to progress to invasive breast cancer. Rates of diagnosis have been increasing with the use of screening mammography that detects pre-clinical microcalcifications. However, the diagnosis of DCIS does require a tissue biopsy. The treatment for DCIS is multidisciplinary and may include surgery, hormone therapy, and radiation therapy.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The evolution of normal breast tissue to DCIS is unknown. There is a genetic predisposition in some but not all patients with DCIS, most notably BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.[3]

Epidemiology

Overall, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the United States. In women aged 50 to 64 years of age, the risk of DCIS is as high as 88 per 100,000 women.[4] Today, 20% to 25% of breast cancer diagnosed in the United States is DCIS. This has increased concurrently with screening mammography, as a significant percentage of DCIS is first identified on screening mammography. In the pre-screening mammography era, less than 5% of newly diagnosed breast cancers were DCIS. A recent 2020 NCI-funded study modeled the natural history of DCIS using a combination of 2 population models and 6 submodels. They found that 36% to 100% of DCIS progressed to invasive breast cancer without surgical excision or treatment, with a mean progression time of 0.2 to 2.5 years. DCIS overdiagnosis ranged from 3.1% to 65.8%. They concluded that the majority of DCIS would progress to invasive breast cancer. However, the wide variation has to do with the heterogeneity and subtype variation within DCIS, and more studies need to be done on various subtypes.[5]

Other risk factors contribute to the progression of DCIS to invasive breast cancer. As a woman ages from birth to death, the probability of developing invasive breast cancer is 12.3% or 1 in 8.[6] Increased exposure to estrogen can also increase the risk of developing breast cancer. The use of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.[7] Additionally, a high endogenous level of estrogen increases the risk of breast cancer; this can be approximated by age at first menarche, age at menopause, and age at first live birth. Alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer as well. Patients with first-degree relatives with breast cancer are at a higher risk of breast cancer.

Histopathology

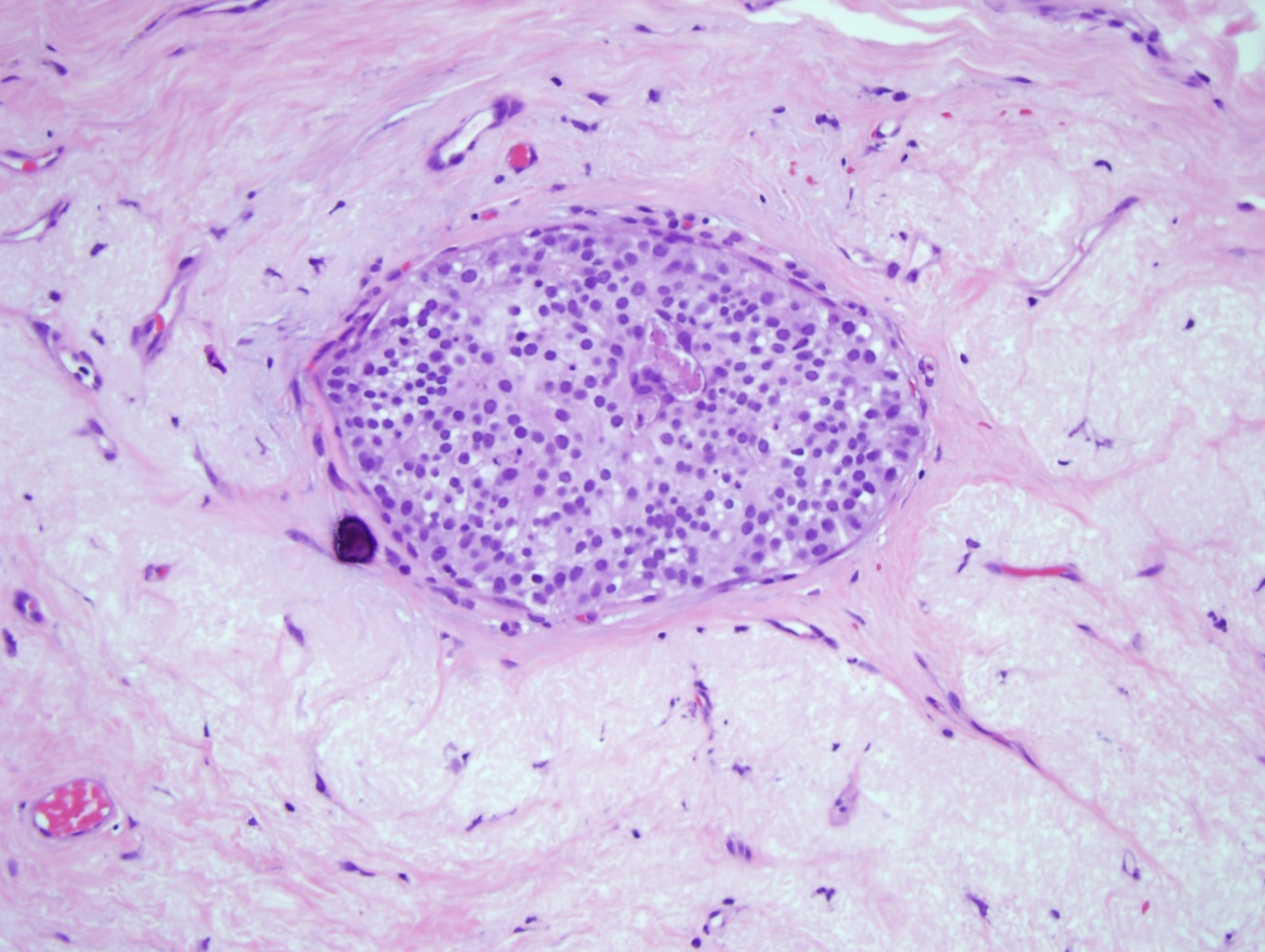

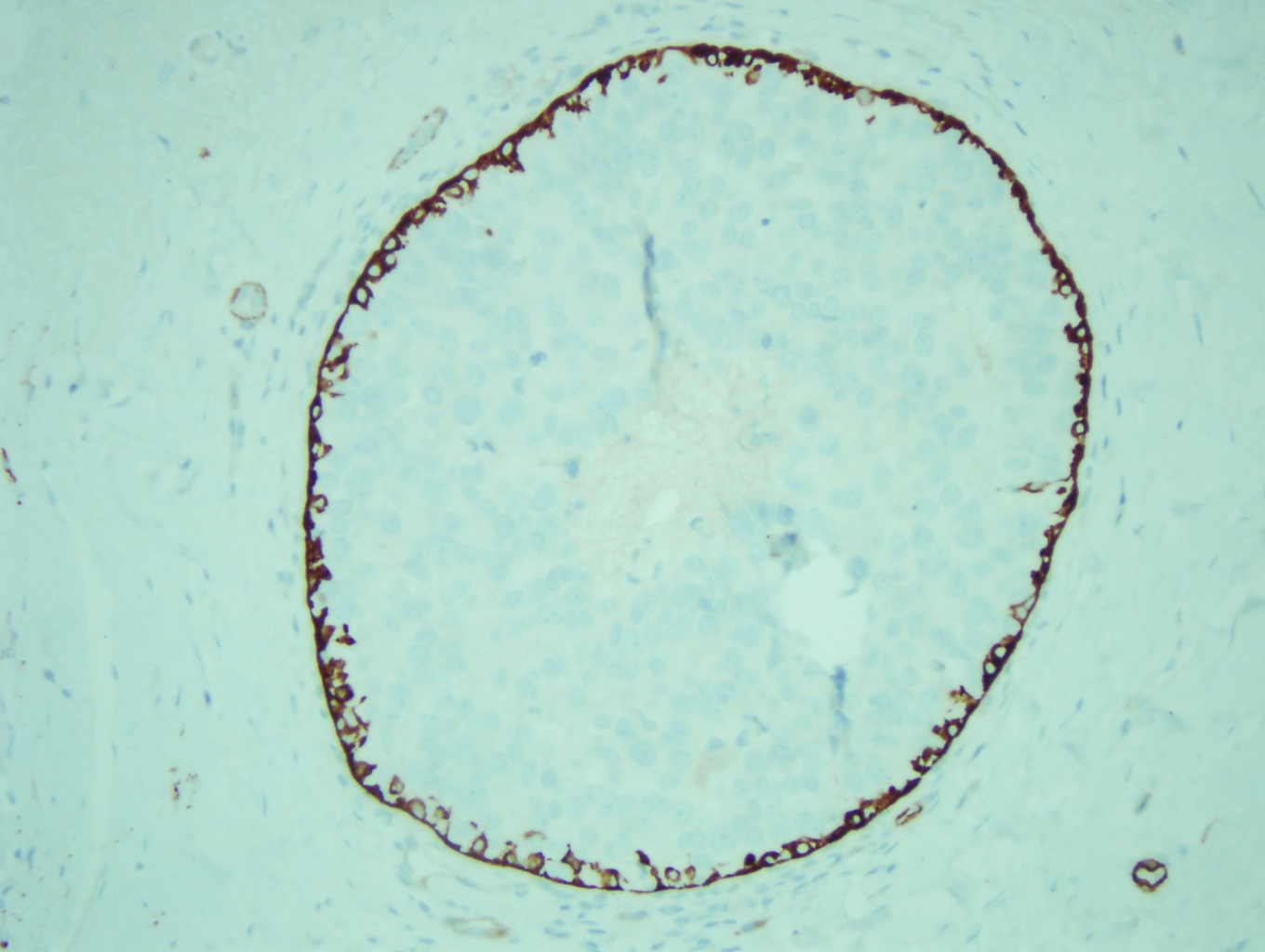

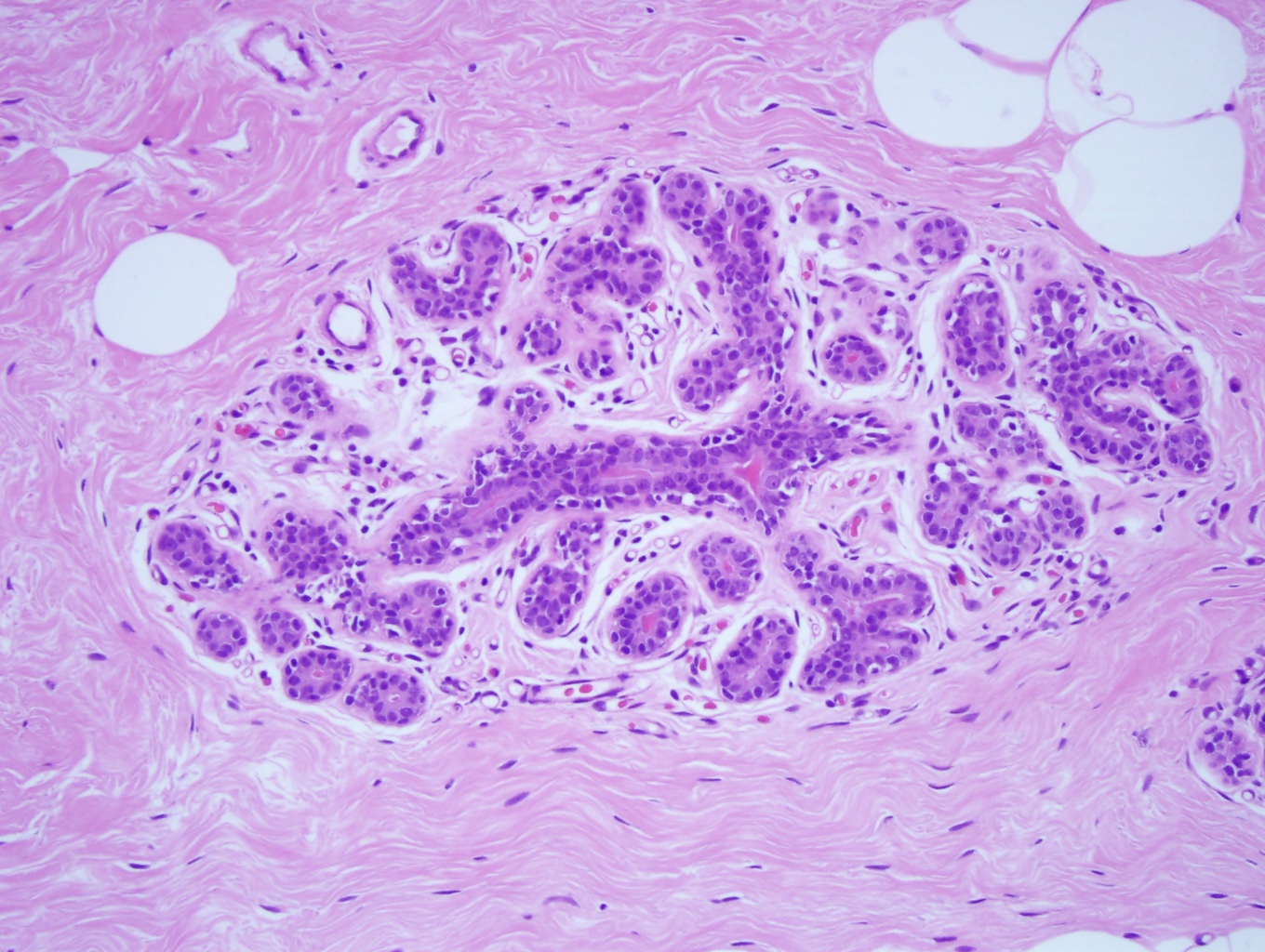

Normal breast ducts terminate into a terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU). See Image. Terminal Duct Lobular Unit. The duct ends into lobules made up of small glandular structures called acini. A bilayer of cells lining the ductal-lobular system consists of inner luminal epithelial cells and outer luminal myoepithelial cells. Most breast lesions (benign or malignant) develop in the TDLU. DCIS is a clonal proliferation of epithelial cells in the breast ductal-lobular unit confined to the myoepithelial cell basement membrane. This confinement demarcates it from invasive breast carcinoma. Immunostains can be performed to show myoepithelial cell retention, such as cytokeratin 5/6, smooth muscle myosin, and p63 (see Image. Myoepithelial Cell Layer). Histologically, DCIS is classified by architecture features, nuclear grade, or the presence of necrosis.

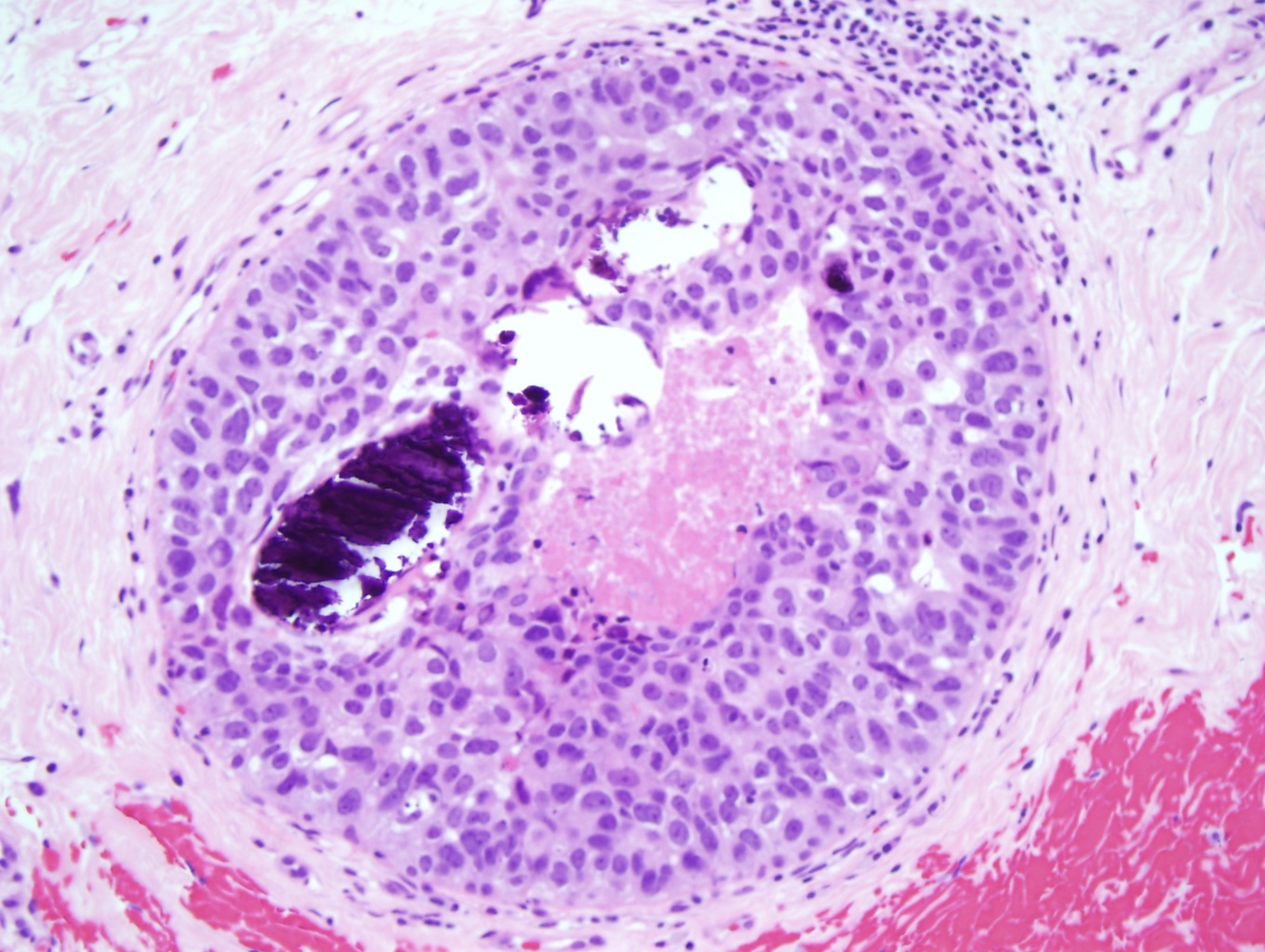

The 5 major architectural patterns are comedo, cribriform, micropapillary, papillary, and solid. In comedo, DCIS, the malignant cells at the center of the duct undergo necrosis, sometimes with calcifications. In cribriforming DCIS, the tumor cells fill the duct and form pseudo-lumens that appear as punched-out spaces. In micropapillary DCIS, the proliferating cells form club-shaped tufts, project into the duct lumen, and lack a fibrovascular core. In papillary DCIS, the cells proliferate around fibrovascular cores. In solid DCIS, the cells fill and distend the duct. It is common to see multiple architectural patterns in DCIS. Micropapillary, cribriforming, and papillary DCIS are considered low-grade lesions. DCIS with solid or comedo features are considered high-grade lesions and have more of a propensity to develop into invasive carcinoma.[8]

DCIS is classified into 3 nuclear grades, which are designated as low, intermediate, or high. Low nuclear grade DCIS is characterized by small cells with uniform size and shape and inconspicuous nucleoli (see Image. Ductal Carcinoma in Situ, Low Grade). High nuclear grade DCIS comprises large cells with pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitosis (see Image. Ductal Carcinoma). Intermediate nuclear grade DCIS is considered when features do not fulfill the low- or high-level DCIS criteria. Intermediate nuclear grade DCIS has mild to moderate changes in nuclear size and shape and a variable amount of mitosis and prominent nucleoli. DCIS, with a high nuclear grade, has more of a likelihood of developing into invasive breast carcinoma (see Image. Invasive Ductal Carcinoma).[9]

History and Physical

A thorough history and physical exam should be included in all breast patients; DCIS is no exception. Regardless of their chief complaint, all breast patients need the same baseline information, including the following: age at menarche, number of pregnancies, number of live births, age at first birth, family history of breast cancer, family history of cancer, history of breast biopsies, alcohol use, duration of use of hormone replacement therapy for postmenopausal women, and use of oral contraception for the premenopausal woman. Any patient identified as a high risk for hereditary breast cancer after taking a detailed family history of cancer should be offered genetic counseling.

A detailed physical exam is also important. Although patients may not have any palpable masses, it is important to perform a physical exam that carefully evaluates breasts and axillae bilaterally for nipple discharge, skin changes, lumps, discharge, and lymphadenopathy when the patients present for evaluation. Many women present for a breast examination after an abnormality has been found on screening mammograms. There may be a range of physical exam findings, from obvious changes in the physical exam to no noticeable external breast changes.

Evaluation

DCIS most commonly presents without a palpable mass and is commonly found via screening mammograms. Ninety percent of all cases of DCIS are detected from screening mammograms.[10] Additionally, if the patient was referred for a suspicious lesion during screening mammography, it is important to perform diagnostic mammography to characterize the ipsilateral disease and rule out bilateral disease. A screening mammogram consists of 2 views of the breast, and it is sensitive but not specific for breast malignancy. On mammograms, the presentation of clustered macrocalcification is common for DCIS. Calcifications associated with malignancy tend to be smaller (0.1 to 1 mm in diameter) and are usually clustered. Microcalcifications that appear in linear branching patterns or segmental types of pleomorphic calcifications are highly suspicious for DCIS.[11] Once suspicious calcifications are identified on screening mammography, it is important to proceed with diagnostic mammography, including additional cuts and information for surgical planning.

Image-guided core needle biopsy performed on the area of suspicion provides a histologic diagnosis. Core needle biopsy allows for more tissue to be sampled compared to fine-needle aspiration; this allows the pathologist to determine if breast cancer is invasive or noninvasive (DCIS). DCIS is architecturally classified as comedo, cribriform, micropapillary, papillary, or solid. Of note, even core needle biopsy has limitations. When core needle biopsy reveals DCIS, there is still a 10% to 20% chance that the final excisional surgical specimen contains invasive carcinoma.[12] Tissue biopsy should also be evaluated for hormone receptor status - particularly estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) status. Although other receptors are being identified and studied, these 3 receptors are important to identify. Specific endocrine treatment modalities can be given to further reduce risk in patients with ER/PR/HER-2 receptor positivity.

With a positive diagnosis of DCIS, the patient needs to proceed to surgery for either breast conservation surgery or total mastectomy. Determination is made based on history and physical exam findings that are important to obtain during the initial evaluation. Cosmesis and the size of the lesion should be taken into consideration. Multifocal, multicentric disease and large lesion size may make breast conservation surgery a less cosmetic option than mastectomy. One must determine if the patient is suitable for breast conservation by evaluating if the patient has a contraindication to post-surgical radiation therapy, such as pregnancy or previous radiation therapy. Information regarding the patient's preferences and ability to follow-up for subsequent treatments with radiation therapy should also be elicited. Additionally, it should be determined on evaluation if the patient needs a referral for genetic counseling. This is determined by a careful personal and family history that uncovers higher than-expected breast and other cancer rates, particularly at young ages. These patients may decide to forgo breast conservation therapy for mastectomy if they discover they have a genetic predisposition to developing breast cancer.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for DCIS is multimodal and involves a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and hormone therapy that is personalized to the patient's specific diagnosis and preferences. Surgical treatment options for DCIS broadly include breast-conserving surgery followed by radiation or a simple mastectomy. With either treatment option, it is important to emphasize that there is equivalent long-term survival.[13] Breast-conserving treatment (BCT) with partial mastectomy and radiation is generally recommended since it is a less surgically invasive procedure. BCT is contraindicated in patients with multicentric disease, an extensive disease where there not be enough remaining breast tissue for cosmesis, and in patients who cannot receive radiation therapy. Mastectomy is curative in 98% of patients with DCIS who undergo it regardless of tumor size or grade.[14](B2)

DCIS, by definition, is noninvasive, and axillary lymph node involvement in DCIS is rare; thus, sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is not indicated during breast-conserving surgery. Data from the NSABP B24 trials demonstrate that axillary recurrence rates, irrespective of treatment (BCT vs mastectomy), were 0.36 per 1000 patient-years of follow-up.[15] For patients undergoing mastectomy for DCIS, an SLN biopsy should be considered since an occult invasive breast cancer could be identified, and an SLN biopsy is often not possible after a mastectomy. Medical management of DCIS consists primarily of endocrine therapy in patients with ER-positive or PR-positive DCIS. The data support that 5 years of endocrine therapy in the appropriate patient does reduce the risk of both ipsilateral and contralateral disease.[16] There is some thought that treating HER-2-positive patients with trastuzumab may also be beneficial. Data available from a 2020 NRG Oncology/NSABP B-43 protocol presented at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) suggest a possible benefit. Still, differences so far are not statistically significant, and more research needs to be done.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to be aware that if a patient has DCIS, there is a real risk the patient already has invasive breast cancer. Approximately 10% to 20% of DCIS lesions diagnosed on core needle biopsy be upgraded to invasive cancer after definitive resection; furthermore, large high-grade DCIS lesions have a higher likelihood of containing an invasive component.[17]

Surgical Oncology

The surgical approach to DCIS is broadly categorized into 2 categories: 1) breast conservation and 2) mastectomy. In this section, we discuss the surgical approach to both.

Breast Conservation

For breast conservation, the first step is pre-surgical localization of the lesion, as many of these lesions are non-palpable and only seen on imaging. This can be done by wire localization immediately pre-procedure or wireless radioactive seed, which can be placed the days before surgery. Both have comparable outcomes when localizing the lesion with negative margins.[18] Surgical planning should also involve reviewing preoperative imaging to determine the depth and location of the mass and make the appropriate incision and resection, considering safety, efficiency, and cosmesis.

The lesion should be excised without entering or damaging the specimen with excessive electrocautery or undue force. A thin buffer of normal breast tissue should be left with the specimen to ensure a 2 mm negative margin on final pathology. Once removed, the specimen should be tagged and oriented in 3-dimensional space using ink or marking suture. Intraoperative X-ray imaging should be performed of the specimen to confirm an intact wire, microclip, seed, and lesion (if the latter is visible on X-ray). After radiologic confirmation of satisfactory biopsy, the area of tissue resection should be inspected and palpated to ensure no other area of concerning tissue warrants resection. Data support a lower risk of positive margins, reoperation, and mastectomy when the surgeon takes additional margins during the index operation in the setting of suspected residual abnormal tissue.[19] Clips should be placed to mark the borders of the lumpectomy site for radiation planning. Care should be taken to ensure hemostasis is achieved before closure.

Post-operatively, the patient needs to undergo radiation therapy. Before initiating radiation therapy, the patient needs pathologic and radiologic confirmation of negative margins from surgery, or a re-operation for additional tissue excision needs to take place. This requires negative margins of 2 mm.[20][21] It also requires a mammogram 1 to 3 weeks after surgery but before initiating radiation therapy to confirm complete excision. Six months after completion of radiation therapy, surveillance mammography should be initiated with yearly imaging. Biannual bilateral breast and lymph node exams are indicated for 2 years and then annually after that.[21] After completing radiation therapy, the patient may consider referral to a plastic or breast oncologic surgeon for oncoplastic reconstruction options.

Mastectomy

For mastectomy, there is no pre-procedural need to localize the lesion. However, sentinel lymph node biopsy is recommended along with mastectomy due to the inability to perform sentinel lymph node biopsy after mastectomy should the lesion be upgraded on final pathology to invasive breast cancer. Surgical planning should consider post-mastectomy plans for reconstruction and cosmesis, particularly in terms of planning a skin-sparing mastectomy, a nipple-sparing mastectomy, the incision choice, and the possible placement of tissue expanders. Therefore, the first pre-operative step after surgical planning is sentinel lymph node mapping with a radioisotope or blue dye (methylene blue, lymphazurin, etc).

Simple mastectomy dissection should be made superiorly to the clavicle, medially to the sternum, inferiorly to the anterior rectus sheath, laterally to the latissimus dorsi, and posteriorly to the pectoralis muscle, making sure to include the pectoralis fascia in the specimen. Ipsilateral sentinel lymph node biopsy should ideally utilize the same incision. Again, hemostasis should be obtained. A drain or 2 should be placed within the mastectomy site. Post-operatively, drains are removed once drain output is less than 30mL in 24 hours. Post-operatively, once the patient has healed from mastectomy and pathology results have been reviewed, the patient may plan for breast reconstruction surgery. Although imaging of the removed breast is not needed for surveillance, the contralateral breast should undergo yearly mammograms. Biannual bilateral breast and lymph node exams are indicated for 2 years and then annually after that.

Radiation Oncology

After obtaining negative margins in partial mastectomy, radiation follows to eliminate any residual disease. The NSABP B17 trial demonstrated that in patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery and were followed with radiation, there is a 50 to 60% reduction in local recurrence with surgical excision and radiation therapy compared to surgical excision alone.[22] Typically, patients undergo whole breast radiation with a total dose of 50 to 60 Gy after breast-conserving therapy. Patients have radiation treatment 5 days a week with 2 Gy fractions of radiation for a total of 5 weeks after the partial mastectomy. The goal is to reduce the risk of locoregional recurrence following surgery by eradicating any persistent locoregional disease.

It is important to recognize medical contraindications for radiation therapy, including pregnancy, previous radiation therapy, and a pacemaker in the radiotherapy field. Other conditions that, in severe cases, are a contraindication include severe pre-existing lung disease that substantially reduces diffusing capacity and connective tissue disorders (scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, etc) with significant vasculitis. Social considerations should be taken into account. The scheduling burden of radiation therapy may not be feasible for patients who lack healthcare access due to insurance or poverty reasons (cannot afford a ride to the hospital, etc) or in rural locations.[23]

Medical Oncology

Chemotherapy is not indicated in patients with DCIS after surgical treatment. However, medical endocrine therapy is a large component of the recommended treatment for DCIS. DCIS is staged as Tis and is Stage 0 breast cancer.[24] Endocrine therapy is recommended if the DCIS specimen expresses estrogen or progesterone receptors. Tamoxifen has been demonstrated to prevent breast cancer recurrences in women with DCIS. In the NSABP B 24 trials, women with ER-positive DCIS treated with tamoxifen had significant decreases in any subsequent breast cancer events when given over 5 years post-diagnosis. This risk reduction is applied to both the ipsilateral and contralateral breast. Interestingly, despite proven reduction in breast cancer recurrences, there is no evidence of survival advantage with endocrine therapy. Therefore, in women who have undergone bilateral mastectomies, the risks of tamoxifen are likely to outweigh the benefits.[16] Tamoxifen is known to increase the risk of endometrial cancer, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism; therefore, before initiating treatment, a thorough risk-benefit analysis should be undertaken with the patient.[25]

Some think that treating HER-2-positive patients with trastuzumab may also be beneficial. Data available from a 2020 NRG Oncology/NSABP B-43 protocol presented at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) suggest a possible benefit, but differences so far are not statistically significant, and more research needs to be done. This area is actively being researched, with new receptors and targeted therapy being developed and studied.

Prognosis

Given the noninvasive nature of DCIS, metastases or death in women with DCIS who are treated are rare.[26] If untreated, however, DCIS usually transforms into invasive cancer that may be deadly. There is an excellent prognosis with a normal life expectancy for the vast majority of patients with DCIS who undergo treatment. However, there is still an increased breast cancer mortality with the diagnosis of DCIS. In a recent 2020 study published in JAMA Oncology of over 100,000 patients diagnosed with DCIS, the overall death rate from breast cancer 20 years after diagnosis was 3.3%, a rate treble that of the general population. That rate was the same with either breast conservation therapy or mastectomy.[27] Interestingly, the same study found the prevention of invasive in-breast recurrence with either radiotherapy or mastectomy did not reduce breast cancer-specific mortality.[27]

A recent meta-analysis from 2019 identified 6 factors that were linked to a higher risk of recurrence of invasive breast cancer. These factors are DCIS found by a doctor during a physical exam, premenopausal, positive margins, high-grade DCIS, high levels of p16 protein, and African American ethnicity.[28] While these results need to be validated by future studies, they highlight that DCIS is heterogeneous. In the future, differentiating between DCIS type and risk factors help guide prognosis and, eventually, treatment to avoid both under and overtreatment.

Complications

Complications vary in severity and frequency and can occur in all stages of treatment. Surgical complications include infection, hematoma, seroma, wound dehiscence, pain, lymphedema, pneumothorax (from wire placement), post-operative flap necrosis (skin flaps too thin), inadequate surgical margins requiring re-excision (skin flaps too thick or poor localization). Positive margins after breast conservation surgery have been reported to range from 20% to 70%. A 2016 study reviewed 567 cases to identify risk factors that lead to positive margins and found that using multiple localizing needles for large lesions, also known as bracketing, resulted in a 2 to 3-fold increased risk of positive margins. The study authors also concluded that intraoperative resection of additional margins during the index surgery resulted in decreased positive margins on final pathology.[19] Another surgical complication causing patient dissatisfaction is a poor cosmetic outcome. This can be addressed preemptively at the index surgery by utilizing oncoplastic techniques or afterward in an additional operation. Medical complications from hormone therapy with Tamoxifen include endometrial cancer, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Complications from radiation therapy include skin and tissue changes (firmer, smaller, discoloration, etc.), fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, rib fractures, and very rarely, angiosarcoma and brachial plexopathy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Understanding that increasing levels of exogenous estrogen increases the risk of breast cancer is important in patient education. Lifestyle and behavioral modifications such as stopping the use of postmenopausal hormones, as well as alcohol use, can decrease a woman's breast cancer risk.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

DCIS treatment is multifaceted and should be tailored to the patient based on pathology, overall health, comorbidities, age, genetics, cosmetic concerns, hormone receptor status, medical access, social support, and patient preference. Therefore, it is paramount for the physician to have a careful discussion with the patient to make an informed decision regarding the treatment plan and ensure care coordination for each patient. These patients need coordination with some or all of the following specialties:

- General surgery/breast surgical oncology

- Radiology

- Medical genetics

- Plastic surgery

- Radiation oncology

- Internal medicine/medical oncology

Care coordination utilizing case managers, social workers, and home health aides, which is crucial for improving access to care, can improve compliance with overall treatment plans in vulnerable populations.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Terminal Duct Lobular Unit. Microscopic anatomy of normal female breast tissue showing a terminal duct lobular unit (×10). The ducts and lobules lumens are open as the epithelial cells do not distend them. Note that the epithelial nuclei overlap, are small and are round, and the nucleoli are inconspicuous and consistent with benign breast tissue.

Contributed by M Khan, DO

(Click Image to Enlarge)

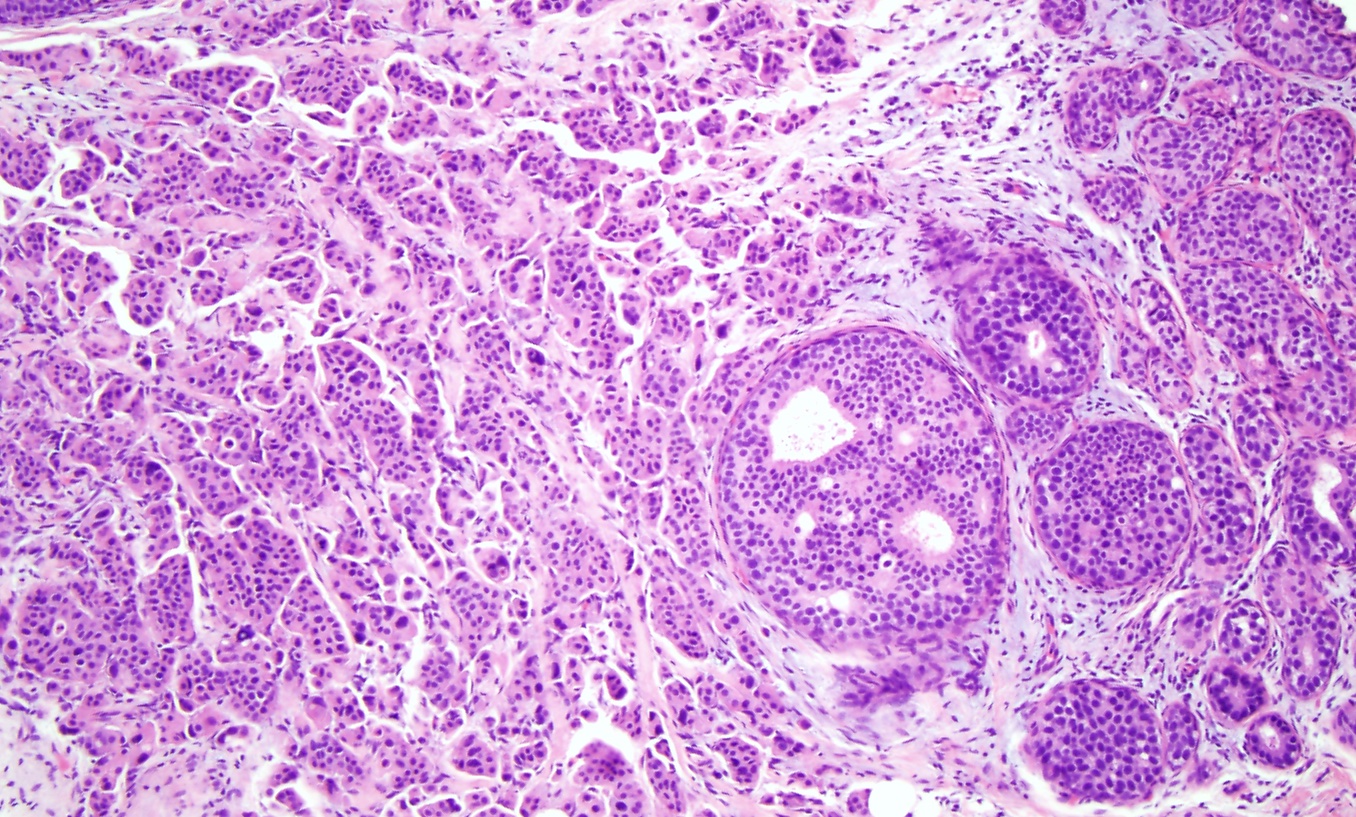

Ductal Carcinoma. The histological slide shows high-grade ductal carcinoma (×10). There is a proliferation of large pleomorphic cells with prominent nucleoli arranged in a solid pattern with comedo necrosis and calcifications. The cellular proliferation does not breach the myoepithelial cell layer, maintaining its in situ nature.

Contributed by M Khan, DO

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma. Histological slide of high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with invasive ductal carcinoma (×10). The left side of the image shows a sheet of cells with pleomorphic nuclei, arranged in tubules, infiltrating into the breast stroma, consistent with invasive ductal carcinoma originating from the adjacent high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ on the right side of the image.

Contributed by M Khan, DO

References

van Seijen M, Lips EH, Thompson AM, Nik-Zainal S, Futreal A, Hwang ES, Verschuur E, Lane J, Jonkers J, Rea DW, Wesseling J, PRECISION team. Ductal carcinoma in situ: to treat or not to treat, that is the question. British journal of cancer. 2019 Aug:121(4):285-292. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0478-6. Epub 2019 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 31285590]

Tan PH, Ellis I, Allison K, Brogi E, Fox SB, Lakhani S, Lazar AJ, Morris EA, Sahin A, Salgado R, Sapino A, Sasano H, Schnitt S, Sotiriou C, van Diest P, White VA, Lokuhetty D, Cree IA, WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the breast. Histopathology. 2020 Aug:77(2):181-185. doi: 10.1111/his.14091. Epub 2020 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 32056259]

Co M, Lee A, Kwong A. Non-surgical treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breasts - a prospective study on patient's perspective. Cancer treatment and research communications. 2021:26():100241. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100241. Epub 2020 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 33340904]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKerlikowske K. Epidemiology of ductal carcinoma in situ. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2010:2010(41):139-41. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20956818]

Chootipongchaivat S, van Ravesteyn NT, Li X, Huang H, Weedon-Fekjær H, Ryser MD, Weaver DL, Burnside ES, Heckman-Stoddard BM, de Koning HJ, Lee SJ. Modeling the natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ based on population data. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2020 May 27:22(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01287-6. Epub 2020 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 32460821]

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014 Jan-Feb:64(1):9-29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. Epub 2014 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 24399786]

Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Gass M, Lane DS, Aragaki AK, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Ockene J, Sarto GE, Johnson KC, Wactawski-Wende J, Ravdin PM, Schenken R, Hendrix SL, Rajkovic A, Rohan TE, Yasmeen S, Prentice RL, WHI Investigators. Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2010 Oct 20:304(15):1684-92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1500. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20959578]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStanciu-Pop C, Nollevaux MC, Berlière M, Duhoux FP, Fellah L, Galant C, Van Bockstal MR. Morphological intratumor heterogeneity in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 2021 Jul:479(1):33-43. doi: 10.1007/s00428-021-03040-6. Epub 2021 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 33502600]

Cutuli B, Lemanski C, De Lafontan B, Chauvet MP, De Lara CT, Mege A, Fric D, Richard-Molard M, Mazouni C, Cuvier C, Carre A, Kirova Y. Ductal Carcinoma in Situ: A French National Survey. Analysis of 2125 Patients. Clinical breast cancer. 2020 Apr:20(2):e164-e172. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2019.08.002. Epub 2019 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 31780381]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDershaw DD, Abramson A, Kinne DW. Ductal carcinoma in situ: mammographic findings and clinical implications. Radiology. 1989 Feb:170(2):411-5 [PubMed PMID: 2536185]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHolland R, Hendriks JH, Vebeek AL, Mravunac M, Schuurmans Stekhoven JH. Extent, distribution, and mammographic/histological correlations of breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Lancet (London, England). 1990 Mar 3:335(8688):519-22 [PubMed PMID: 1968538]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMannu GS, Wang Z, Broggio J, Charman J, Cheung S, Kearins O, Dodwell D, Darby SC. Invasive breast cancer and breast cancer mortality after ductal carcinoma in situ in women attending for breast screening in England, 1988-2014: population based observational cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2020 May 27:369():m1570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1570. Epub 2020 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 32461218]

Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, Mamounas EP, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Land SR, Margolese RG, Swain SM, Costantino JP, Wolmark N. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011 Mar 16:103(6):478-88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027. Epub 2011 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 21398619]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee LA, Silverstein MJ, Chung CT, Macdonald H, Sanghavi P, Epstein M, Holmes DR, Silberman H, Ye W, Lagios MD. Breast cancer-specific mortality after invasive local recurrence in patients with ductal carcinoma-in-situ of the breast. American journal of surgery. 2006 Oct:192(4):416-9 [PubMed PMID: 16978940]

Julian TB, Land SR, Fourchotte V, Haile SR, Fisher ER, Mamounas EP, Costantino JP, Wolmark N. Is sentinel node biopsy necessary in conservatively treated DCIS? Annals of surgical oncology. 2007 Aug:14(8):2202-8 [PubMed PMID: 17534687]

Allred DC, Anderson SJ, Paik S, Wickerham DL, Nagtegaal ID, Swain SM, Mamounas EP, Julian TB, Geyer CE Jr, Costantino JP, Land SR, Wolmark N. Adjuvant tamoxifen reduces subsequent breast cancer in women with estrogen receptor-positive ductal carcinoma in situ: a study based on NSABP protocol B-24. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Apr 20:30(12):1268-73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0141. Epub 2012 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 22393101]

Houssami N, Ciatto S, Ellis I, Ambrogetti D. Underestimation of malignancy of breast core-needle biopsy: concepts and precise overall and category-specific estimates. Cancer. 2007 Feb 1:109(3):487-95 [PubMed PMID: 17186530]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAgahozo MC, Berghuis SAM, van den Broek E, Koppert LB, Obdeijn IM, van Deurzen CHM. Radioactive Seed Versus Wire-Guided Localization for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast: Comparable Resection Margins. Annals of surgical oncology. 2020 Dec:27(13):5296-5302. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08744-8. Epub 2020 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 32578065]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEdwards SB, Leitman IM, Wengrofsky AJ, Giddins MJ, Harris E, Mills CB, Fukuhara S, Cassaro S. Identifying Factors and Techniques to Decrease the Positive Margin Rate in Partial Mastectomies: Have We Missed the Mark? The breast journal. 2016 May:22(3):303-9. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12573. Epub 2016 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 26854189]

[Structural studies of generalized abnormalities of the dental hard tissues. 2]., Vahl J,Sluka H,, Deutsche zahnarztliche Zeitschrift, 1978 Jun [PubMed PMID: 28928852]

Morrow M, Van Zee KJ, Solin LJ, Houssami N, Chavez-MacGregor M, Harris JR, Horton J, Hwang S, Johnson PL, Marinovich ML, Schnitt SJ, Wapnir I, Moran MS. Society of Surgical Oncology-American Society for Radiation Oncology-American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline on Margins for Breast-Conserving Surgery With Whole-Breast Irradiation in Ductal Carcinoma in Situ. Practical radiation oncology. 2016 Sep-Oct:6(5):287-295. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.06.011. Epub 2016 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 27538810]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, Mamounas E, Costantino J, Poller W, Fisher ER, Wickerham DL, Deutsch M, Margolese R, Dimitrov N, Kavanah M. Lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-17. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998 Feb:16(2):441-52 [PubMed PMID: 9469327]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZhang S, Liu Y, Yun S, Lian M, Komaie G, Colditz GA. Impacts of Neighborhood Characteristics on Treatment and Outcomes in Women with Ductal Carcinoma In Situ of the Breast. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2018 Nov:27(11):1298-1306. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1102. Epub 2018 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 30108100]

Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Annals of surgical oncology. 2010 Jun:17(6):1471-4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20180029]

Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cecchini RS, Cronin WM, Robidoux A, Bevers TB, Kavanah MT, Atkins JN, Margolese RG, Runowicz CD, James JM, Ford LG, Wolmark N. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005 Nov 16:97(22):1652-62 [PubMed PMID: 16288118]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRoses RE, Arun BK, Lari SA, Mittendorf EA, Lucci A, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM. Ductal carcinoma-in-situ of the breast with subsequent distant metastasis and death. Annals of surgical oncology. 2011 Oct:18(10):2873-8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1707-2. Epub 2011 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 21476105]

Giannakeas V, Sopik V, Narod SA. Association of a Diagnosis of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ With Death From Breast Cancer. JAMA network open. 2020 Sep 1:3(9):e2017124. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17124. Epub 2020 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 32936299]

Visser LL, Groen EJ, van Leeuwen FE, Lips EH, Schmidt MK, Wesseling J. Predictors of an Invasive Breast Cancer Recurrence after DCIS: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2019 May:28(5):835-845. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0976. Epub 2019 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 31023696]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence