Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Psoas Major

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Psoas Major

Introduction

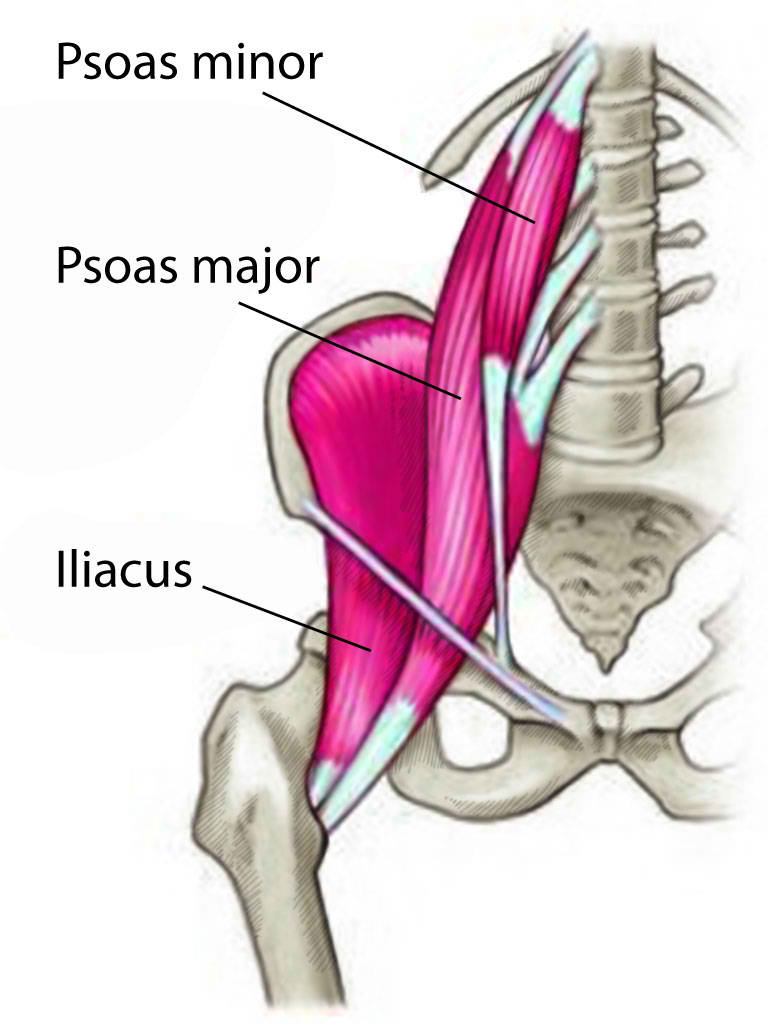

The psoas muscle is among the most significant muscles that overlie the vertebral column. It is a long fusiform muscle on either side of the vertebral column and the brim of the lesser pelvis. At its distal end, it combines with the iliacus muscle to form the iliopsoas muscle. The psoas muscle has traditionally described having a deep and superficial segment. The deeper segment of the muscle originates from the first four lumbar vertebrae, while the superficial segment originates along the lateral surface of the distal thoracic vertebrae and from adjacent intervertebral discs. In between the deep and superficial layers, one can find the lumbar plexus. At the distal end, the psoas muscle combines with the iliacus muscle to form the iliopsoas muscle which is encircled by the dense iliac fascia. The common tendon attaches on the lesser trochanter of the femur: the muscle during contraction of the fibers lead to external rotation and abduction of the femur. The orientation of the muscle changes from the superior-inferior direction of the upper portion to a horizontal direction toward anterior of the middle portion reaching the pubic branch and passing under the inguinal ligament, and to an oblique direction toward posterior of the distal portion of the tendon inserting on the lesser trochanter. The inconsistent psoas minor muscle completes the psoas muscle.

The psoas major muscle has a biomechanical and postural function during both moving and static states. It is also involved in the metabolic function used in the clinical assessment of some diseases,[1] as well as mood and stress disorders as a cause of low back pain.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The classical anatomy textbooks, like Testut, describe the psoas major muscle originating at the top of the lateral face and the base of the transverse processes of the first four lumbar vertebrae and from the twelfth thoracic vertebrae and interposed intervertebral discs. The insertion on the discs and on the transverse processes is through short tendon tongues, which insert on the vertebral body with a medially concave arched tendon to allow passage of the lumbar vessels and the communicating branches of the ortho-sympathetic nerves.

From the lumbar spine the numerous muscular bundles move forward, downwards, and laterally to form a single, cylindrical and fusiform muscular body, it presents the maximum thickness at the sacroiliac joint. The muscle crosses the lumbar region and the iliac fossa, from which it emerges through an incisura on the upper margin of the ilio-pubic branch between the inferior anterior iliac spine and the iliopectineal eminence (lacuna musculorum). At this level, the posterior fascicles attach firmly to the pelvic brim, and the muscle fibers change direction taking it posteriorly and laterally to insert itself through a thick tendon on the posterior face of the small trochanter of the femur.[3]

The iliacus muscle has a fan-shaped triangular shape that occupies the internal iliac fossa. It originates on the upper two-thirds of the iliac fossa, on the medial edge of the iliac crest, on the ilium-lumbar ligament, where it blends with the bundles of the quadratus lumborum muscle, on the base of the sacrum, anteriorly on the upper and lower anterior iliac spines, and finally on the anterior capsule of the hip joint. The muscular bundles move towards the lateral side of the psoas major muscle tendon on which they are inserted. Few lateral and inferior muscle bundles are inserted directly on the femur.The psoas minor muscle is an inconsistent and small muscle bundle that often turns into fibrous tissue, it is present in around 60-65% of the population.[4]. It originates from the corpus of the last thoracic vertebra and from the first lumbar and from the interposed disc and is located anteriorly and medially to the large psoas muscle. It has the shape of a flattened and thin ribbon and fits on the iliopectineal eminence and the iliac fascia.

Psoas bursa. The psoas muscle is separated from the bony margin of the ilium and from the fibrous capsule of the hip joint by a serous fluid bursa (the iliopectineal bursa) of considerable size that sometimes communicates with the synovial space of the hip joint. A smaller bursa is located between the muscle tendon and the anterior surface of the lesser trochanter of the femur.

Fascial Relationship

The iliopsoas muscle has important fascial relationships in its upper or lumbar abdominal portion, in its medial portion in the iliac fossa near the inguinal ligament, and in its femoral portion in the lower limb.

Lumbo-pelvic portion. The psoas major muscle sits in a posterior relationship to the diaphragm, to the psoas minor muscle, to the kidney and the renal vessels, to the ureter, to the gonadal vessels, to the ascending colon on the right and descending to the left. It is positioned anteriorly to the inter-transversal muscles of the transverse apophysis of the vertebrae on which it is inserted, with the quadratus lumborum muscle, from which it is separated from the deep sheet of the thoracolumbar fascia,[5], and from the anterior branches of the lumbar nerves. Its right medial margin corresponds to the inferior vena cava and to the descending portion of the duodenum, the left medial margin is related to the aorta, with the ascending portion of the duodenum and the duodenojejunal flexure. Inferiorly it is crossed by the ureter and the common iliac vessels and runs parallel to the common iliac vessels. The psoas muscle is crossed by the lumbar plexus branches, which emerge from its surface: anteriorly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the genitofemoral nerve; medially the lumbosacral trunk and the obturator nerve; laterally the iliohypogastric nerve, the ilioinguinal nerve, and the femoral nerve. One must be aware that the lumbar plexus and peripheral branches have huge anatomical variability.[6] The iliac muscle is posteriorly positioned to the cecum on the right and the sigmoid colon on the left; its posterior surface rests in the iliac fossa and is related to the fibrous capsule of the sacroiliac joint, the iliolumbar ligaments and the deep branches of the iliac circumflex vessels. The iliolumbar ligaments are an integrative part of the thoracolumbar fascia following the posterior aspect of the psoas major muscle that is covered by the deep layer of the thoracolumbar fascia and continues superiorly with the endo thoracic fascia.[5]

Inguinal portion. The iliopsoas muscle passes under the inguinal ligament, filling all the space between the ligament, the iliopectineal band and the anterior border of the iliac bone: a space called the lacuna musculorum. The iliopectineal band separates it from the artery and femoral vein. The femoral nerve is located on the anteromedial side.

Femoral portion. The lateral surface of the iliopsoas muscle constitutes the lateral portion of Scarpa's triangle. Its posterior side rests above the fibrous capsule of the hip joint. Its medial margin corresponds to the lateral edge of the pectoral muscle with which it forms a groove for passaging the femur artery. Its lateral margin is related to the sartorial muscle and the rectus femoris muscle.

Function

The function of the psoas muscle is to connect the upper body to the lower body, the outside to the inside, the appendicular to the axial skeleton, and the front to the back, with its fascial relationship. Combined with the iliopsoas muscle, the psoas is a major contributor of flexion of the hip joint. Unilateral contraction of the psoas also helps with lateral motions and bilateral contraction can help elevate the trunk from the supine position. The psoas muscle also works in conjunction with the hip flexors to elevate the upper leg towards the body when the body is static or pull the body towards the leg when the leg is in a fixed position.

The biomechanical and postural function of the psoas complex muscle is to flex the hip, to adduct the femur and to externally rotate the hip. In an upright position, the muscle takes a fixed point on the femur and acts on the pelvis and on the lumbar spine. Its action is to flex the spine, to side-bend ipsilateral and to rotate it towards the opposite side. The proper role of the psoas major muscle is to stabilize the lumbar spine in the sitting position and to flex the femur in a supine or standing position.[4] The psoas major acts as a stabilizer of the femoral head in the hip acetabulum in the first 15 degrees of movement, maintains the erector action from 15° to 45°, and it is an effective flexor of the femur from 45° to 60°.[7] It seems that the lower fascicles flex the lower lumbar spine and the upper fascicles to extend the upper lumbar vertebrae: the flexion-extension movement is small, whereas the compression and shear forces are large, collapsing the spine in a sigmoid fashion and forcing it into lordosis while severely straining the lumbosacral segment.[8][9] An anchoring retinaculum at the level of the lumbosacral junction keeps the psoas muscle in place alongside the lumbar spine, making its action on the increase of the lumbar lordosis independent of the lumbar curvature. During gait movements, the ipsilateral psoas muscle is activated during the onset of the hip flexion and during the latter part of the swing phase.[10]

The psoas major is in relationship with the medial arcuate ligament and continues with the thoracic diaphragm and the endo thoracic fascia: the psoas major muscle seems able to exert influence on the balance of the dynamics of respiratory function and the functional relationship between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor. The fascia of the muscle appears to exhibit continuity with the fascia of the crus of the diaphragm, blending with the anterior longitudinal ligament; while the inferomedial fascia of the psoas muscle becomes thick and is continuous with the deep fascia of the pelvic floor[3]: this forms a link with the conjoint tendon, transversus abdominis muscle, and the internal oblique muscle. From this point of view, the psoas muscle may influence the pelvic floor functions, the balance between the pelvic floor movements with the rhythm of the thoracic diaphragm; it may be involved in the venous and lymphatic drainage of abdomen, pelvis and lower limbs.

Embryology

Literature does not describe the embryology of the psoas major muscle in detail. A 3-D reconstruction study of 8 weeks gestation embryos shows that the muscles of the iliac region are well recognizable in their spatial organization and orientation, as in adult anatomy. From origin to insertion the major psoas muscle and the iliacus muscle were noticeably separated from each other: in adults specimens, this distinction is not so evident at their inferior end where the tendons fuse to form the iliopsoas muscle.[11]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The psoas major muscle is supported by collateral rami of the lumbar arteries, by the iliolumbar arteries, circumflex iliac artery, obturator artery, and femoral artery.

Nerves

The psoas major muscle is innervated via the anterior rami of L1-L4, and also receives small branches from the femoral nerve.

Muscles

The psoas major muscle has a different size: the superior portions are smaller in diameter than the inferior portion and are located more posterior to the axes of flexion-extension of the lumbar segment.[9] The muscle is more substantial on the side of the dominant leg at all four vertebral levels measured, and studies on subjects who reported current low back pain were found to have larger psoas muscles when compared with pain-free control subjects with smaller cross-sectional area.[3][12]

The length of the fleshy fascicular parts of the psoas major muscle (but not the tendinous portion which was not analyzed), was found to be similar on the left and the right side (cm. 14.5 ± 2.9 and 14.6 ± 2.8 respectively), with a sagittal angle of 10.0° and a frontal angle of 23.3°. The anatomical cross-sectional area was found to be different comparing the two sides (4.4 cm2 vs. 3.3 cm2.) and demonstrated greater architectural subunit variability between the body's left and right sides, and among specimens.[13]

The psoas major muscle is composed of type I, IIA and IIX muscle fibers: but is mainly composed of type IIA fibers (59.28%), which indicates an essential dynamic function, but the composition of the muscle fibers varies according to the anatomical level examined. The fibers type composition changes at the levels of its origin from the first to the fourth lumbar vertebra, which suggests a primarily postural role of the superior part (type IIA fibers), and a predominantly dynamic function of the inferior portion of the muscle (type I fibers).[14] So, summarizing, the fiber type is mixed (40% type I, 50% type IIa, and 10% type IIx) with a 60:40 predominance of fast fibers[1]

Surgical Considerations

The psoas major muscle is prone to lesions of surgical interest. Pyogenic abscesses are rarely primary; most are secondary to bowel infection (Crohn's disease, appendicitis, diverticulitis, perforating colon carcinoma, perinephric abscess). Hemorrhage and hematoma diffuse the muscle, causing an enlargement mass, chronic hematoma could be confused with abscess, necrotic tissue, or tumor. These lesions are spontaneous due to atherosclerosis or secondary to trauma, biopsy or surgery procedure, anticoagulant therapy, or disorders of the coagulation system. Primary tumors are rare: liposarcoma, fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and hemangiopericytoma. Malignancy is secondary to retroperitoneal or pelvic cancers (lymphoma, colon, ovarian, uterine, cervical, urinary tract and sarcoma). Other conditions involving the psoas muscle are the retroperitoneal fibrosis, muscle calcification, rhabdomyolysis, and atrophy. Clinical history, imaging techniques (CT or MR scan), and biopsy are ancillary procedure before surgical therapy, where appropriate.[15]

Clinical Significance

Surgical conditions are to be differentiated from other more common complaints. When the psoas muscle is inflamed or irritated, it can cause low back pain by compression of the thoracic and lumbar discs. Also, inflammation of the psoas muscle can also lead to entrapment and compression of the nerve branches of the related lumbar plexus. Lumbar neuralgias may present as a sensation of water or heat running down the anterior aspect of the thigh. Surgical procedures approaching anteriorly to the psoas muscle can lead to nerve injury.[16]

In thin people, the psoas muscle may is palpable with the hip in active flexion or 30° flexion, medial to the anterior superior iliac spine. When manual therapists palpate the psoas muscle, care should be taken to avoid injury to the colon. Reproducing the patient's pain on palpation is a reliable indicator of myofascial pain; then evaluation of the related structures must be completed.[3]. In psoas major myofascial pain, a list of differentials will include psoas bursitis, osteoarthritis, renal calculi, psoas tendinitis, labral tear, psoas strain (major and/or minor), intra-articular bodies, psoas abscess, joint infection, coxa saltans/iliopsoas tendinitis, inflammatory arthritides/gout, femoral stress fracture, iliotibial band, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, rectus femoris, femoral bone tumor, adductor muscles, iliacus, hernia, lumbar spine or sacroiliac joint referral, and obturator nerve entrapment. The psoas muscle can react to disease or inflammation occurring in the closer related visceral organs leading to psoas spasm with benign conditions: colitis, hiatal hernia, dysbiosis, leaky gut syndrome, or irritable bowel syndrome.

Clinically psoas major myofascial pain presents symptoms similar to low back pain, pain in the groin and pelvis, radiating pain towards knee; the primary function of psoas muscle that is hip flexion (hence difficulty walking) and sustaining fully erect posture is difficult to achieve. Extended sitting is a cause of shortening/cramping of the muscle with pain; the many flexor muscles can compensate for a weak psoas muscle. A psoas dysfunction and psoas spasm can cause a restriction in the movement of the thoracic diaphragm that potentially causes more disability in the back muscles than other conditions.[17]. A psoas spasm may lead to compression of the lumbar spine and hyper-lordosis with shearing stress of the lumbosacral joint [9].

Other Issues

Psoas cross-sectional area relates to the quality of the condition of many parts of the body. Spinal degeneration associated with low back pain correlates with the diameter of the muscle as do atrophic changes regarding unilateral lumbar disc herniation and unilateral back pain.[18] The psoas muscle functions as a convenient and straightforward marker of sarcopenia, the loss of whole body muscle mass: a condition related to a variety of diseases including cirrhosis,[19] cancers,[20] peripheral artery disease,[21] aortic valve disease,[22] and type 2 diabetes mellitus.[23] Quantitative data from CT scans on psoas muscle shows a relationship to a variety of clinical outcomes, with the overall concept that low psoas amount would predict morbidity or mortality.[1] Nutritional adequacy in hospitalized patients shows an association with the deteriorating quality of the psoas muscle; the gain in psoas density was related to a shorter hospital stay in a surgical intensive care unit.[24]

Low back pain involves the spine muscles, both the posterior and the anterior (psoas major muscle); they are influenced in their motor responses by nociceptive stimuli, showing a generalized and widespread decrease in lumbar muscle activity during the periods of remission of recurrent low back pain. Patients seem to have structural and functional alterations at multiple peripheral and central levels along the sensorimotor pathway; changes in lumbar muscle structure and at the proprioceptive level have been described, and the cortical representation of specific lumbar muscles appeared to show some level or reorganization. Muscular response studied with functional MRI is altered by muscular performance as well as subject fear in performing certain activities or movements.[25]

Low back pain, anxiety, and mood disorders are widely studied and closely related.[26][27][28] The organic cause of the pain is not always clearly identified, leading to the investigation of the neural circuits of interoception, proprioception, kinesthesis, and visceral pain. All of these involve the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the motor and premotor system (increased muscle tension and preparedness to act), the endocrine system, emotional areas, and the central nervous system ("fight-or-flight" reaction).[29] The lumbar lordosis angle and the grade of the pelvic tilt were studied in relationship with the balance of the two parts of the autonomic nervous system, orthosympathetic and parasympathetic (vagus nerve).[30] The psoas major musculature is one of the principal actors in the complex neural network of human psycho-somatic experience and the reactive stress system, potentially involved in the incidence, but also the relief, of the post-traumatic stress disorder.[2] In consideration of the psoas muscle from many points of view, it may be a potential link between different levels of the human being, suitable to be treated with a multidisciplinary approach.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Baracos VE. Psoas as a sentinel muscle for sarcopenia: a flawed premise. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2017 Aug:8(4):527-528. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12221. Epub 2017 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 28675689]

Andersen TE, Lahav Y, Ellegaard H, Manniche C. A randomized controlled trial of brief Somatic Experiencing for chronic low back pain and comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. European journal of psychotraumatology. 2017:8(1):1331108. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1331108. Epub 2017 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 28680540]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSajko S, Stuber K. Psoas Major: a case report and review of its anatomy, biomechanics, and clinical implications. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2009 Dec:53(4):311-8 [PubMed PMID: 20037696]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnderson CN. Iliopsoas: Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clinics in sports medicine. 2016 Jul:35(3):419-433. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2016.02.009. Epub 2016 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 27343394]

Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec:221(6):507-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01511.x. Epub 2012 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 22630613]

Anloague PA, Huijbregts P. Anatomical variations of the lumbar plexus: a descriptive anatomy study with proposed clinical implications. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy. 2009:17(4):e107-14 [PubMed PMID: 20140146]

Yoshio M, Murakami G, Sato T, Sato S, Noriyasu S. The function of the psoas major muscle: passive kinetics and morphological studies using donated cadavers. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. 2002:7(2):199-207 [PubMed PMID: 11956980]

Bogduk N, Pearcy M, Hadfield G. Anatomy and biomechanics of psoas major. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon). 1992 May:7(2):109-19. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(92)90024-X. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23915688]

Penning L. Psoas muscle and lumbar spine stability: a concept uniting existing controversies. Critical review and hypothesis. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2000 Dec:9(6):577-85 [PubMed PMID: 11189930]

Penning L. Spine stabilization by psoas muscle during walking and running. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2002 Feb:11(1):89-90 [PubMed PMID: 11931072]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWarmbrunn MV, de Bakker BS, Hagoort J, Alefs-de Bakker PB, Oostra RJ. Hitherto unknown detailed muscle anatomy in an 8-week-old embryo. Journal of anatomy. 2018 Aug:233(2):243-254. doi: 10.1111/joa.12819. Epub 2018 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 29726018]

Stewart S, Stanton W, Wilson S, Hides J. Consistency in size and asymmetry of the psoas major muscle among elite footballers. British journal of sports medicine. 2010 Dec:44(16):1173-7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058909. Epub 2010 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 19474005]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStark H, Fröber R, Schilling N. Intramuscular architecture of the autochthonous back muscles in humans. Journal of anatomy. 2013 Feb:222(2):214-22. doi: 10.1111/joa.12005. Epub 2012 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 23121477]

Arbanas J,Klasan GS,Nikolic M,Jerkovic R,Miljanovic I,Malnar D, Fibre type composition of the human psoas major muscle with regard to the level of its origin. Journal of anatomy. 2009 Dec [PubMed PMID: 19930517]

Torres GM, Cernigliaro JG, Abbitt PL, Mergo PJ, Hellein VF, Fernandez S, Ros PR. Iliopsoas compartment: normal anatomy and pathologic processes. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1995 Nov:15(6):1285-97 [PubMed PMID: 8577956]

Buckland AJ, Beaubrun BM, Isaacs E, Moon J, Zhou P, Horn S, Poorman G, Tishelman JC, Day LM, Errico TJ, Passias PG, Protopsaltis T. Psoas Morphology Differs between Supine and Sitting Magnetic Resonance Imaging Lumbar Spine: Implications for Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Asian spine journal. 2018 Feb:12(1):29-36. doi: 10.4184/asj.2018.12.1.29. Epub 2018 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 29503679]

Tufo A, Desai GJ, Cox WJ. Psoas syndrome: a frequently missed diagnosis. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2012 Aug:112(8):522-8 [PubMed PMID: 22904251]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArbanas J, Pavlovic I, Marijancic V, Vlahovic H, Starcevic-Klasan G, Peharec S, Bajek S, Miletic D, Malnar D. MRI features of the psoas major muscle in patients with low back pain. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2013 Sep:22(9):1965-71. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2749-x. Epub 2013 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 23543369]

Huguet A, Latournerie M, Debry PH, Jezequel C, Legros L, Rayar M, Boudjema K, Guyader D, Jacquet EB, Thibault R. The psoas muscle transversal diameter predicts mortality in patients with cirrhosis on a waiting list for liver transplantation: A retrospective cohort study. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.). 2018 Jul-Aug:51-52():73-79. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.01.008. Epub 2018 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 29605767]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRutten IJG, Ubachs J, Kruitwagen RFPM, Beets-Tan RGH, Olde Damink SWM, Van Gorp T. Psoas muscle area is not representative of total skeletal muscle area in the assessment of sarcopenia in ovarian cancer. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2017 Aug:8(4):630-638. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12180. Epub 2017 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 28513088]

Swanson S, Patterson RB. The correlation between the psoas muscle/vertebral body ratio and the severity of peripheral artery disease. Annals of vascular surgery. 2015 Apr:29(3):520-5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2014.08.024. Epub 2014 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 25463328]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHawkins RB, Mehaffey JH, Charles EJ, Kern JA, Lim DS, Teman NR, Ailawadi G. Psoas Muscle Size Predicts Risk-Adjusted Outcomes After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018 Jul:106(1):39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.02.010. Epub 2018 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 29530777]

Murea M, Lenchik L, Register TC, Russell GB, Xu J, Smith SC, Bowden DW, Divers J, Freedman BI. Psoas and paraspinous muscle index as a predictor of mortality in African American men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of diabetes and its complications. 2018 Jun:32(6):558-564. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.03.004. Epub 2018 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 29627372]

Yeh DD, Ortiz-Reyes LA, Quraishi SA, Chokengarmwong N, Avery L, Kaafarani HMA, Lee J, Fagenholz P, Chang Y, DeMoya M, Velmahos G. Early nutritional inadequacy is associated with psoas muscle deterioration and worse clinical outcomes in critically ill surgical patients. Journal of critical care. 2018 Jun:45():7-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.12.027. Epub 2018 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 29360610]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDanneels L, Cagnie B, D'hooge R, De Deene Y, Crombez G, Vanderstraeten G, Parlevliet T, Van Oosterwijck J. The effect of experimental low back pain on lumbar muscle activity in people with a history of clinical low back pain: a muscle functional MRI study. Journal of neurophysiology. 2016 Feb 1:115(2):851-7. doi: 10.1152/jn.00192.2015. Epub 2015 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 26683064]

Jain R. Pain and the brain: lower back pain. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2009 Feb:70(2):e41 [PubMed PMID: 19265640]

Sheng J, Liu S, Wang Y, Cui R, Zhang X. The Link between Depression and Chronic Pain: Neural Mechanisms in the Brain. Neural plasticity. 2017:2017():9724371. doi: 10.1155/2017/9724371. Epub 2017 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 28706741]

Thompson EL, Broadbent J, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Bertino MD, Staiger PK. A Network Analysis of the Links Between Chronic Pain Symptoms and Affective Disorder Symptoms. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2019 Feb:26(1):59-68. doi: 10.1007/s12529-018-9754-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30377989]

Payne P, Levine PA, Crane-Godreau MA. Somatic experiencing: using interoception and proprioception as core elements of trauma therapy. Frontiers in psychology. 2015:6():93. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00093. Epub 2015 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 25699005]

Cottingham JT, Porges SW, Richmond K. Shifts in pelvic inclination angle and parasympathetic tone produced by Rolfing soft tissue manipulation. Physical therapy. 1988 Sep:68(9):1364-70 [PubMed PMID: 3420170]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence