Introduction

The electrocardiogram (abbreviated as ECG or EKG) represents an electrical tracing of the heart and is recorded non-invasively from the surface of the body. The word ECG derives from the German language. In German, it is elektro-kardiographie. In 1902, the Dutch physician Einthovan invented ECG, and his tremendous input in clinical studies for about ten years led to full recognition of the clinical potential of the technique.[1]

Many arrhythmias and ECG changes associated with angina and atherosclerosis were identified by 1910. William Einthoven was named the "father of electrocardiography" and was awarded Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1924 for his hard work that laid the foundation of the most fundamental technique for investigating heart disorders. ECG was soon recognized as a robust screening and clinical diagnostic tool, and today it is used globally in almost every healthcare setting.[2]

ECG is a non-invasive diagnostic modality that has a substantial clinical impact on investigating the severity of cardiovascular diseases.[3] ECG is increasingly being used for monitoring patients on antiarrhythmics and other drugs, as an integral part of preoperative assessment of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery, and for screening individuals in high-risk occupations and those participating in sports. Also, ECG serves as a research tool for surveillance and experimental trials of drugs with recognized cardiac effects.[4]

Cardiovascular disease, as the number one cause of death, puts a great emphasis on healthcare providers developing skills and knowledge in interpreting ECGs to provide the best care promptly. Many healthcare providers find the advanced interpretation of ECG findings a complicated task. Errors in the analysis can lead to misdiagnosis, delaying the appropriate treatment. This activity seeks to provide a general understanding of the ECG mechanisms, interpretation techniques, and commonly encountered ECG findings.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

A basic understanding of cardiac anatomy and coronary distribution is essential to understanding electrocardiographic findings.

The heart is a vital body organ and occupies space in the central chest between the lungs. Together with the blood vessels and blood, it constitutes the body's circulatory system. The heart is a muscular organ comprised of four chambers with two atria (right and left) opening into right and left ventricles via tricuspid and mitral valves, respectively. A wall of muscle called the septum separates all four chambers. The heart receives deoxygenated blood from the whole body via superior and inferior vena cava, which first enters the right atrium. From here, it transits through the right ventricle and then passes into the lungs via the right and left pulmonary arteries, where it is oxygenated. The oxygenated blood from the lungs pours into the left atrium through the right and left pulmonary veins, and from here, it is pumped by the left ventricle into the aorta to the rest of the body. The heart derives its blood supply from the coronary arteries that branch off the aorta.[5]

The right and left coronary arteries lie on the surface of the heart. With considerable heterogeneity among the general population, different regions of the heart receive vascular supply from the various branches of the coronary arteries. This anatomic distribution is significant because a 12-lead ECG assesses these cardiac regions to help localize and diagnose ischemic or infarcted areas. Written below are the following regions supplied by the different coronary arteries.

- Inferior Wall - Right coronary artery

- Anteroseptal - Left anterior descending artery

- Anteroapical - Left anterior descending artery (distal)

- Anterolateral - Circumflex artery

- Posterior Wall - Right coronary artery

The heart is a mechanical pump whose activity is governed by the electrical conduction system.[6] It is essential to possess a strong understanding of the physiology of the cardiac cells as this will help the reader appreciate how the heart works and the implications of findings on the ECG. The heart is made up of specialized cardiac muscle, which is striated and organized into sarcomeres. These muscle fibers contain a single central nucleus, numerous mitochondria, and myoglobin molecules.

Extensive branching of the cardiac muscle fibers and their end-to-end connection with each other through intercalated discs make them contract in a wave-like fashion. This mechanical work of pumping blood to the whole body occurs in a synchronized manner and is under the control of the cardiac conduction system. It is comprised of two types of cells, pacemaker and non-pacemaker cells. Pacemaker cells are located primarily in the SA and AV node, and it is the SA node that drives the rate and rhythm of the heart. The AV node gets suppressed by the more rapid pace of the SA node.[7]

The specialized function associated with the pacemaker cells is their spontaneous depolarization with no true resting potential. When spontaneous depolarization reaches the threshold voltage, it triggers a rapid depolarization followed by repolarization. The non-pacemaker cells mainly comprise the atrial and ventricular cardiac muscle cells and Purkinje fibers of the conduction system. They consist of true resting membrane potential, and upon initiation of an action potential, rapid depolarization is triggered, followed by a plateau phase and subsequent repolarization. Action potentials are generated by ion conductance via the opening and closing of the ion channels. Knowing which ECG leads corresponds to specific arteries helps localize the obstruction in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction or an age-indeterminate Q-wave infarction by observing predictable patterns on the ECG.[8]

Indications

The evolution of electrocardiograms from a string galvanometer to the modern-day advanced computerized machine has led to its use as a diagnostic and screening tool, making it the gold standard for diagnosing various cardiac diseases.

Owing to its widespread use in the field of medicine, the ECG has several indications listed below:

- Symptoms are the foremost indication of the ECG, including palpitation, dizziness, cyanosis, chest pain, syncope, seizure, and poisoning

- Symptoms or signs associated with heart disease include tachycardia, bradycardia, and clinical conditions including hypothermia, murmur, shock, hypotension, and hypertension

- To detect myocardial injury, ischemia, and the presence of prior infarction

- Rheumatic heart disease[9]

- ECG changes in cases like drowning and electrocution are very valuable in determining necessary interventions[10]

- Detecting pacemaker or defibrillator device malfunction, evaluating their programming and function, verifying the analysis of arrhythmias, and monitoring for delivery of the appropriate electrical pacing in patients with defibrillators and pacemakers[11]

- Evaluation of metabolic disorders

- Helpful for the assessment of blunt cardiac trauma[12]

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Valuable aid in the study and differential diagnosis of congenital heart diseases[13]

- Electrolyte imbalance and rhythm disorders[14]

- To monitor the pharmacotherapeutic effects and adverse effects of drug therapy

- Perioperative anesthesia monitoring, such as preoperative assessment and intraoperative and postoperative monitoring

- Screening tool in a sports physical exam to rule out cardiomyopathy[15]

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications for an electrocardiogram. The relative contraindications to its use include:

- Patient refusal

- Allergy to the adhesive used to affix the leads

Equipment

The American College of Cardiology (ACC), in conjunction with American Heart Association (AHA) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), has formulated guidelines and set technical standards for ECG equipment.[16] With advancements, most ECG machines have become digital and can autogenerate preliminary findings based on the morphology criteria.

The conventional ECG machine consists of 12 leads divided into two groups, i.e., limb leads and precordial leads. Limb leads are further categorized as standard bipolar limb leads (I, II, and III) and augmented unipolar leads (aVL, aVF, and aVR). The precordial leads include V1 to V6. The limb leads view the heart in a vertical plane, and the precordial leads record the heart's electrical activity in the horizontal plane. The ECG represents a graphic recording of the electrical cardiac activity traced on the electrocardiograph paper.[17] The fundamental principle behind recording an ECG is an electromagnetic force, current, or vector with both magnitude and direction. When a depolarization current travels towards the electrode, it gets recorded as a positive deflection, and when it moves away from the electrode, it appears as a negative deflection.

- A current of repolarization traveling away from the positive electrode is seen as a positive deflection and towards a positive electrode as a negative deflection.

- When the current is perpendicular to the electrode, it touches the baseline and produces a biphasic wave.

These concepts are easily applied to the heart while recording the ECG. Several types of ECG monitoring equipment are available, including continuous ECG monitoring, hardwire cardiac monitoring, telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography, transtelephonic monitoring, wireless mobile cardiac monitoring systems, etc.[18][19] Furthermore, a duo of ECG and electronic stethoscopes have been designed into a portable, handheld device that can review ECG rhythms and intervals at the bedside for analysis. With the evolution of technology, there are electronic wristwatches that can also monitor the heart rate and rhythm and have proven to be of value in detecting atrial fibrillation.[20] However, the accuracy of these devices may be somewhat inferior compared to a 12-lead ECG. When prompted for abnormal findings, these require confirmation by standardized clinical testing available in the cardiology office.

The equipment for performing a conventional 12-lead ECG includes:

- Electrodes (sensors)

- Gauze and skin preparation (alcohol rub) solution

- Razors, clippers, or a roll of tape (for hair removal)

- Skin adhesive and/or antiperspirant

- ECG paper

- Cardiac monitor or electrocardiography machine

Personnel

Any medical personnel who has received training on conducting an electrocardiogram can obtain an ECG, including a doctor, nurse, qualified technician, etc. Usually, it is performed by the technicians in clinics or hospitals and then interpreted by clinicians. Often, these findings are confirmed by a cardiologist in a hospital-based setting.

Preparation

Electrocardiogram requires special preparation. Before the procedure, a brief history regarding drugs and allergies to adhesive gel is necessary. The temperature of the room must be kept optimal to avoid shivering. The patient should be in a gown, and electrode sites identified. For good contact between the body surface and electrodes, it is advised to shave the chest hair and then apply the electrocardiographic adhesive gel to the electrodes. Any metallic object, like jewelry or a watch, requires removal. Limb and precordial leads should be accurately placed to avoid vector misinterpretation. Finally, the patient must lie down and relax before recording the standard 10-second strip.

Technique or Treatment

Electrocardiogram machines are designed to record changes in electrical activity by drawing a trace on a moving electrocardiograph paper. The electrocardiograph moves at a speed of 25 mm/sec. Time is plotted on the x-axis and voltage on the y-axis. On the x-axis, 1 second is divided into five large squares, each representing 0.2 sec. Each large square is further divided into five small squares of 0.04 sec each. The ECG machine is calibrated in such a way that an increase of voltage by one mVolt should move the stylus by 1 cm.

The conventional 12-lead ECG consisting of six limbs and six precordial leads is organized into ten wires.[21] The limb leads include I, II, III, aVL, aVR, and aVF and are named RA, LA, RL, and LL. The limb leads are color-coded to avoid misplacement (red - right arm, yellow - left arm, green - left leg, and black - right leg). The precordial leads V1 to V6 are attached to the surface of the chest.[22] For the correct location, the "angle of Louis" method is an option, and the exact placement is as follows:

- V1 is placed to the right of the sternal border, and V2 is situated to the left of the sternal edge.

- V4 is placed at the level of the fifth intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line. V4 should be placed before V3. V3 is placed between V2 and V4.

- V5 is placed directly between V4 and V6.

- V6 is placed at the level of the fifth intercostal space in the mid-axillary line.

- V4 through V6 should line up horizontally along with the fifth intercostal space.

Complications

An electrocardiogram is a safe, non-invasive, painless test with no major risks or complications. An allergic reaction or skin sensitivity to the adhesive gel can occur and usually resolves as soon as the electrode patches are removed and, in most cases, do not require any treatment. Artifacts and distortions pose serious diagnostic difficulties and may result in an inaccurate interpretation of the ECGs, potentially resulting in an adverse therapeutic intervention.[23][24]

There can be a potential for misdiagnosis due to the inadvertent misplacement of ECG leads.[25][26]

Clinical Significance

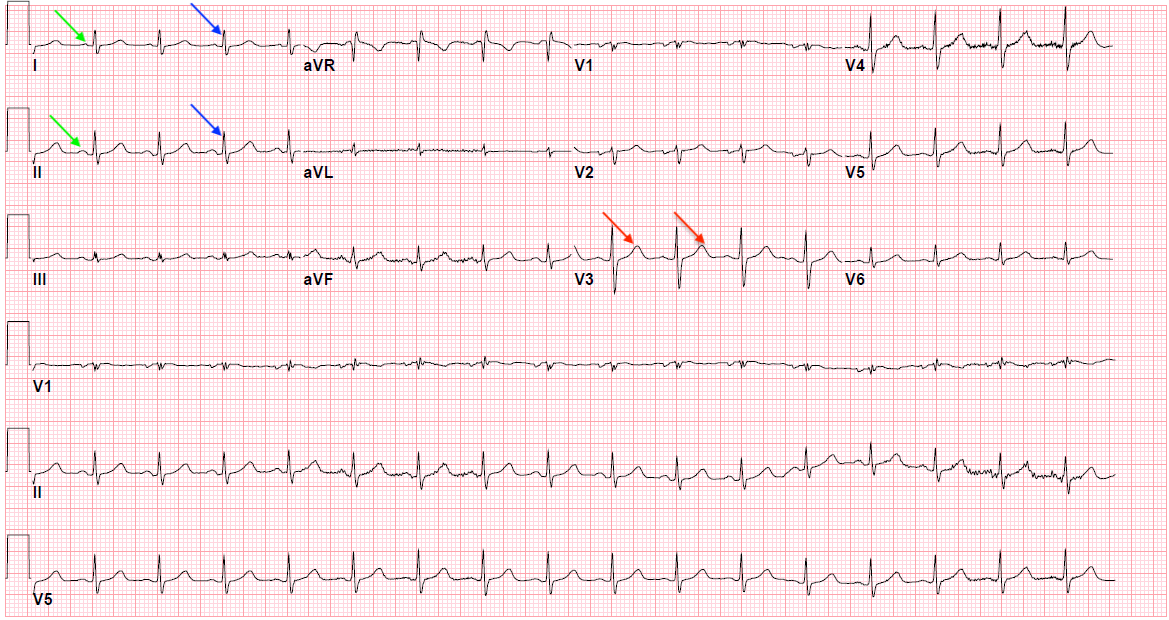

The goal of the electrocardiogram interpretation is to determine whether the ECG waves and intervals are normal or pathological. Electrical signal interpretation gives a good approximation of heart pathology. A standard 12 lead ECG is shown in [Figure 1]. The best way to interpret an ECG is to read it systematically:

Rate

For the calculation of rate, the number of either small or large squares between an R-R interval should be calculated. The rate can be calculated by either dividing 300 by the number of big squares or 1500 by the number of small squares between two R waves. For an irregular rhythm, count the number of beats in a 10-second strip and multiply it by 6.[27] Normal HR is 60 to 99 beats per minute. If it is less than 60, it is called bradycardia, and if greater than 100/min, it is referred to as tachycardia.

Rhythm

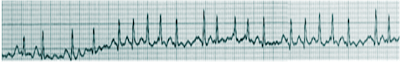

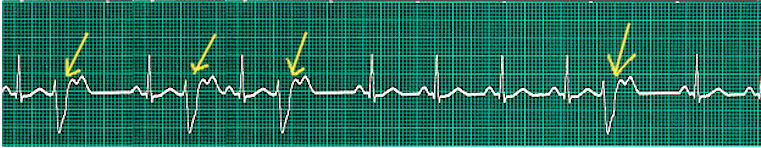

The leads I, II, aVF, and V1, require inspection for an accurate interpretation of rhythm. It involves looking for five points: the presence or absence of regular P waves, the duration of QRS complexes (narrow or wide), the correlation between P waves and QRS complexes, whether the rhythm is regular or irregular, and the morphology of P waves. A regular rhythm ECG has regular P waves preceding a QRS complex in a regular rhythm. Also, normal sinus rhythm demonstrates positive P waves in leads I, II, and aVF, suggesting a downward propagation of atrial activation from the SA node. These features also help identify if the arrhythmia originates in the atria or ventricles.[28] Many disorders are related to rhythm abnormalities. For example, no real P waves can be seen in atrial fibrillation due to the very fast atrial activity. Only a few impulses get delivered to ventricles making the rhythm irregularly irregular. The presence of 'irregularly irregular' narrow QRS complexes with no discrete P waves is the hallmark feature in the identification of atrial fibrillation.

Cardiac Axis

It refers to the direction of the heart's depolarization wavefront in the frontal plane. The cardiac axis is related to the area of significant muscle bulk within the healthy conducting system. A typical cardiac axis is between -30 to +90 degrees. A quick way to estimate the axis is by looking at leads I and aVF. It can be defined as a normal axis when the QRS complex is positive in leads I and aVF. A left axis deviation (between 0 and -90 degrees) is defined by the presence of positive QRS in the lead I and negative in lead aVF, and a right axis deviation (+90 and 180 degrees) by the presence of negative QRS in the lead I and positive in the lead aVF. If both QRS complexes are negative in leads I and aVF, it is an extreme right-axis deviation or indeterminate axis (-90 to 180 degrees).[29] Other methods used to determine the cardiac axis include three-lead analysis, isoelectric lead analysis, etc.

There are several disorders in which the cardiac axis deviates. Examples include old inferior myocardial infarction, left ventricular hypertrophy, and left bundle branch block where left axis deviation occurs while noting right axis deviation in conditions including right ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary hypertension, hyperkalemia, and wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome, etc. The specific criteria on ECG for atrial and ventricular hypertrophy are devised from examining various leads and wave morphologies: for atrial abnormality (enlargement or hypertrophy), leads II and V1 are usually assessed. Right atrial hypertrophy increases the amplitude in the first half of the P waves by 2.5 mm in inferior leads and a possible right axis deviation.[30] It is often termed P pulmonale because of its frequent association with chronic obstructive lung disease. Left atrial hypertrophy shows an increase in the amplitude of the terminal component and duration of the P wave. It must descend at least 1 mm below the isoelectric line in lead V1 and be at least 0.04 seconds (40 ms) in width. As the left atrium is electrically dominant, it shows no axis deviation.[31]

The diagnosis of ventricular hypertrophy requires looking at several leads on the ECG. The right ventricular hypertrophy characteristically shows by right axis deviation along with the presence of a more significant R wave than the S wave in lead V1, whereas in lead V6, a more significant S wave than the R wave.[32] Left ventricular hypertrophy is characterized by voltage criteria either by calculating the voltage of the R wave in V5 or V6 plus the S wave in V1 or V2 exceeding 35 mm or by the voltage of the R wave exceeding 13 mm in lead aVL. Infrequently, there is also the presence of secondary repolarization abnormalities, including asymmetric T wave inversion and downsloping ST-segment depression, commonly also referred to as the strain pattern; the left axis deviation often accompanies this.[33]

P-wave

It represents atrial depolarization on the ECG. As atrial depolarization initiates by the SA node located in the right atrium, the right atrium gets depolarized first, followed by left atrial depolarization. So the first half of the P wave represents right atrial depolarization and the second half shows left atrial depolarization. Its duration is three small squares wide and 2.5 small squares high. It is always positive in the lead I and II and consistently negative in lead aVR in normal sinus rhythm. It is commonly biphasic in lead V1. An abnormal P wave may indicate atrial enlargement.[34]

PR Interval

It represents the time from the beginning of atrial depolarization to the start of ventricular depolarization and includes the delay at the AV node. The average interval is 3 to 5 small squares (120 to 200 ms).[35] Variations in the PR interval can lead to various disorders. Long PR interval may indicate first-degree AV block, and short interval may be present in conditions with accelerated AV conduction, such as the presence of bypass tract or Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome and Lown-Ganong-Levine syndrome.

Heart Block

A conduction block can occur due to any obstruction in the normal pathway of electrical conduction. Their anatomical location can be categorized as sinus node, atrioventricular node, or bundle branch blocks.

- Sinus node or sinoatrial exit block occurs due to failed propagation of the impulses beyond the SA node resulting in dropped P waves on the ECG. Common causes include sick sinus syndrome, increased vagal tone, inferior wall MI, vagal stimulation, myocarditis, drugs including digoxin, beta-blockers, etc.[36]

- Atrioventricular or AV block is a conduction block that can occur anywhere between the SA node and Purkinje fibers. There are three variants of AV blocks: first-degree, second-degree, and third-degree. Clinically significant points in diagnosing the AV blocks include careful measurement of the PR interval and examining the relationship of the P waves to QRS complexes.

- First-degree heart block is defined as prolonging the PR interval by more than 200 milliseconds.[37] A single P wave precedes every QRS complex. It may be a normal finding in some individuals. Still, it can be an early sign of degenerative disease of the conduction system or a transient manifestation of myocarditis or drug toxicity, hypokalemia, acute rheumatic fever, etc. It usually does not require any treatment.[38]

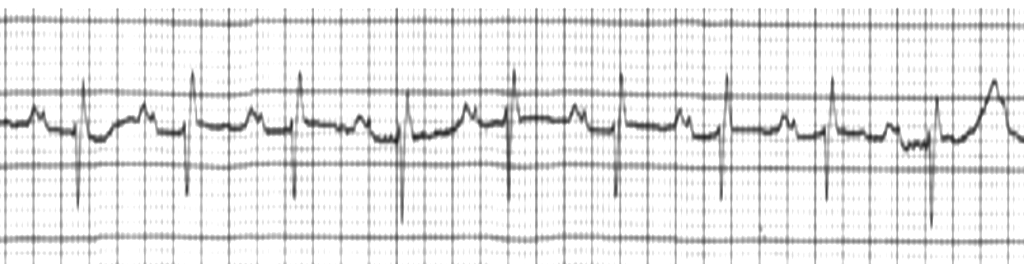

- Second-degree heart block is of two types, i.e., Mobitz type I (also known as Wenkebach block) and Mobitz type II. In type I, the block across the AV node or bundle of His is variable and increases with each ensuing impulse, ultimately resulting in a drop of the impulse (usually every third or fourth impulse). On ECG, it shows a progressive prolongation of the PR interval, and then suddenly, a P wave is not followed by the QRS complex.[39] This sequence regularly repeats itself. Most patients with Mobitz type I second-degree AV block are asymptomatic. Mobitz type I AV block may occur in the setting of acute myocardial ischemia or myocarditis. It may also result in clinical deterioration if the resulting ventricular rate is inadequate to maintain cardiac output. Most patients with Mobitz type I second-degree AV block are asymptomatic and do not require specific intervention. Rarely patients with Mobitz type I block are symptomatic and demonstrate hemodynamic instability, and may require treatment with either atropine (emergently) or cardiac pacing. In type II AV block, there is a dropped beat without the progressive lengthening of the PR interval.[40] It follows the all-or-nothing phenomenon. It usually occurs below the AV node at the level of the bundle of His. It clinically signifies a severe underlying heart disease that can progress to third-degree heart block. When diagnosed, it usually requires prompt treatment with a permanent pacemaker.

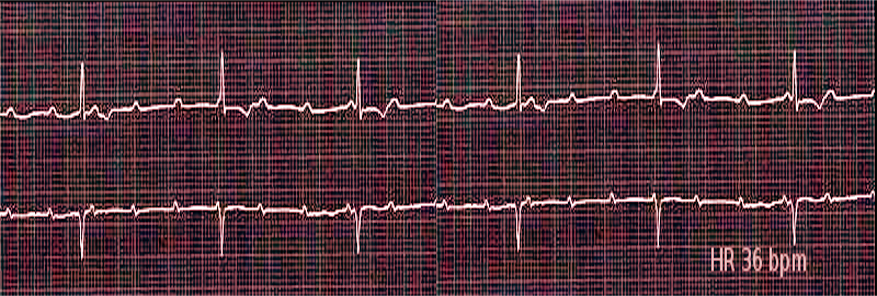

- Third-degree heart block is characterized by a complete electrical dissociation between the atria and ventricles, resulting in the atria and the ventricles beating at their intrinsic rates. Degenerative disease of the conduction system is the leading cause of third-degree heart block. A complete heart block may present in acute myocardial infarction.[41] Complete heart block may be reversible with prompt revascularization, especially in inferior MI. Lyme disease may be associated with a complete heart block and is potentially reversible with antibiotic therapy. In the case of irreversible or permanent complete heart block, a permanent pacemaker remains the mainstay of the treatment.

- Bundle branch block results from the conduction block of either left or right bundle branches. It gets diagnosed by examining the width and configuration of the QRS complexes. The right bundle branch block is represented on the ECG by the presence of a widened QRS complex greater than 0.12 seconds, along with an RSR pattern in V1 and V2. Also, there may be ST-segment depression and T wave inversions and reciprocal changes in leads V5, V6, I, and aVL. Conduction system disorders can cause the right bundle branch block, but it may be present as a standard variant in specific individuals. The left bundle branch block is represented on the ECG by a widened QRS complex greater than 0.12 seconds, broad or notched R wave with prolonged upstroke in the leads V5, V6, I, and aVL, along with ST-segment depression and T wave inversion, and reciprocal changes in leads V1 and V2. Usually, a left-axis deviation is also present. The left bundle branch usually signifies an underlying pathology, such as degenerative disease of the conduction system or ischemic heart disease.[42]

QRS Complex

It represents ventricular depolarization as current passes down the AV node. A standard QRS complex has a duration of less than three small squares (under 120 ms, usually 60 to 100 ms). A prolonged QRS may indicate hyperkalemia or bundle branch block. Conversely, a premature ventricular contraction or a ventricular rhythm can be associated with a wide QRS.

Septal Q-Wave

Q-wave often appears as a tiny negative deflection in leads I, aVL, V5, and V6. It represents the depolarization of the interventricular septum. Its amplitude is not bigger than 0.1 mV, so septal depolarization is not always visible on the ECG. Pathological Q-waves on ECG can signify an old infarct. A Q-wave duration greater than 40 milliseconds (one small box), depth greater than 1 mm, or a size greater than 25% of the QRS complex amplitude is pathologic.[43]

R-Wave

It is the tallest wave of the QRS complex, representing the electrical stimulus as it passes down the ventricles during depolarization. The R-wave progressively increases in amplitude, moving right to the left in the precordial leads, and is called R-wave progression. Lead V1 has the smallest R wave, and lead V5 has the largest. A reduced R-wave progression has several causes, including prior anteroseptal MI, left ventricular hypertrophy, inaccurate lead placement, etc.[44]

S-Wave

It represents the final depolarization of the Purkinje fibers. It is any downward deflection after R-wave. It may not be present in all ECG leads. S-wave is most significant in V1 and progressively becomes smaller to no S-wave in the lead V6.

T-Wave

It represents ventricular repolarization. Its morphology is highly susceptible to cardiac and noncardiac influences like (hormonal and neurological). It is usually positive in leads with tall R-waves (upward deflection). The suggested criteria for the typical T wave include the size of one-eighth or less than two-thirds of the size of the R wave and a height of less than 10 mm.

Abnormalities in the T-wave morphology include inverted, flat, biphasic, or tall tented T-waves. T waves can be helpful in a variety of pathologies; tall T waves in anterior chest lead III, aVR, and V1 with a negative QRS complex may suggest acute myocardial ischemia.[45] Other causes of T wave abnormalities are caused by physiological factors (e.g., postprandial state), endocrine or electrolyte imbalance, myocarditis, pericarditis, cardiomyopathy, postcardiac surgery state, pulmonary embolism, fever, infection, anemia, acid-base disorders, drugs, endogenous catecholamines, metabolic changes, acute abdominal process, intracranial pathology, etc.[46]

ST-Segment

It depicts the end of ventricular depolarization and the beginning of ventricular repolarization. The average duration of the ST segment is less than 2 to 3 small squares (80-120 ms). ST-segment is an isoelectric line and lies at the same level as PR-interval. Elevation or depression of the ST segment by 1 mm or more, measured at J point, is abnormal. A J point is a region between the QRS complex and the ST segment. ST-elevation is highly specific if present in two or more contiguous leads in the setting of acute myocardial infarction. If the vertical distance on the ECG trace and the baseline after the J-point is at least 1 mm in a limb lead or 2 mm in a precordial lead, it is clinically significant for diagnosing acute myocardial infarction.

Correct ST segment interpretation is crucial as a type of ST-segment elevation is present in healthy individuals due to early repolarization, called J-point elevation. It is distinguished by the fact that the T wave does not merge with the ST segment and remains an independent wave. Several other disorders are also associated with ST-elevation, i.e., Prinzmetal angina, acute pericarditis, acute myocarditis, hyperkalemia, blunt trauma, pulmonary embolism, subarachnoid hemorrhage, Brugada syndrome, ventricular aneurysm, and left bundle branch block.[47][48][49]

ST-elevations are diffuse in acute pericarditis and associated with PR-depression about TP-segments (except for leads V1 and aVR).[50][51][52][53] In myocardial infarction, the ST elevation tends to be localized (inferior, anterior, posterior, lateral), often, but not always, with reciprocal ST depression.[54] Secondly, the PR segment displacement is attributable to the subepicardial atrial injury. PR elevation can present in aVR, and PR depression is best seen in II, aVF, and V4-V6. PR-depression and slight downsloping appearance of TP segments are often known as Spodick sign of pericarditis and help distinguish acute pericarditis from acute MI.[54]

ST depression greater than 1 mm is often a sign of myocardial ischemia or angina. It can appear as a downsloping, upsloping, or horizontal segment on the ECG. A horizontal or downsloping ST depression greater than 0.5 mm at the J-point in two contiguous leads indicates myocardial ischemia. An upsloping ST depression in the precordial leads with prominent De Winter T waves is highly indicative of MI caused by occlusion of the left anterior descending artery.[55]

ST depression can represent a reciprocal change with a morphology that resembles "upside-down" ST elevation and is typically seen in leads electrically opposite to the site of infarction. For example, posterior wall MI manifests as horizontal ST depression in leads V1-3 and is associated with tall R waves and upright T waves. Likewise, inferior wall STEMI produces reciprocal ST depression in leads I and aVL, and there is often a reciprocal ST depression in leads III and aVF in lateral wall MI.[55] ST depressions are also associated with non-ischemic causes, including digoxin toxicity, hypokalemia, hypothermia, and tachycardia.[56]

QT Interval

It represents the start of depolarization to the end of the repolarization of ventricles. The normal QT interval duration is somewhat controversial, and various normal durations have been previously suggested. Generally, the normal QT interval is less than 400 to 440 milliseconds (ms), or 0.4 to 0.44 seconds. Women usually have a slightly longer QT interval than men. A QT interval has an inverse relation to the heart rate. A prolonged QT interval presents an imminent risk for serious ventricular arrhythmias, including Torsades de Pointes, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation. A common cause of QT prolongation includes medications, electrolyte abnormalities such as hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia, and congenital long QT syndrome.[57]

A short QT interval ( less than 360 milliseconds) may be associated with hypercalcemia, acidosis, hyperkalemia, hyperthermia, or short QT syndrome.[58]

U Wave

It is a small wave that follows the T wave. It represents the delayed repolarization of the papillary muscles or Purkinje fibers. It is commonly associated with hypokalemia.

J Wave

Also known as the Osborn wave, it is an abnormal ECG finding in hypothermia. It appears as an extra deflection on ECG at the QRS complex and ST-segment junction.[59]

Epsilon Wave

It is a small positive deflection usually found buried at the end of the QRS complex as a characteristic finding in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia.[60]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The use of an electrocardiogram has expanded from simple heart rate and essential rhythm monitoring to interpreting complex arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, and other ECG abnormalities. The rapid detection of myocardial infarction has substantially reduced the door-to-balloon time for reperfusion therapy. Nurses' skills regarding assessment and comprehensive knowledge of the dysrhythmias can prevent stroke in atrial fibrillation and improve patient outcomes from the emergency department presentation through discharge and follow-up.[61] Cardiology board-certified pharmacists can make appropriate medication recommendations for several medications, particularly antiarrhythmics, based on ECG readings and patient history, working in conjunction with the cardiologist.

ECG outcomes in management are noticeable in every department within the interprofessional healthcare team. Interaction among clinicians (MDs and DOs, including specialists, NPS, and PAs), nurses, patient care assistants, pharmacists, and ECG technicians is critical to providing the most effective patient care. Interprofessional collaboration and teamwork in the hospital setting prevent significant medical errors through multiple checkpoints and ensure timely emergency care in cardiac emergencies. For better outcomes, excellent professional ethics, patient satisfaction, and staff proficiency in evaluating ECGs are mandatory. There should be effective, open communication between interprofessional team members with appropriate role clarity, shared policies, and strategies to improve system-related issues to drive optimal patient outcomes.[62][63][64] [Level 5]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Continuous EKG monitoring is one of the current technologies used in the emergency department, intensive, post-anesthesia, and cardiac care units. Often, nurses are the first care responders in these hospital settings. The first interaction of the EKG view puts great responsibility on the nurses in managing technical aspects of the EKG monitoring and decision-making on the clinical grounds with information received from the monitor. The current practice includes that nurses initially interpret the EKG, gather data, and promptly notify the physician-in-charge to ensure an appropriate management plan.[65]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Among the healthcare providers in a hospital setting, especially in intensive and cardiac care units where round-the-clock monitoring of critical patients is required, nurses play a very crucial role in cardiac monitoring. It is the nurse's responsibility to assess the patient's clinical condition, monitor, and ensure that an excellent quality of care is delivered. The nurses' should monitor the continuous EKG monitoring very carefully and have competency in initial interpretation. Their knowledge about correct EKG leads placement, analysis, and thrombolytic treatment in acute coronary syndrome patients have significant implications for reducing morbidity and mortality.[66]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Krikler DM. Historical aspects of electrocardiography. Cardiology clinics. 1987 Aug:5(3):349-55 [PubMed PMID: 3319160]

Fye WB. A history of the origin, evolution, and impact of electrocardiography. The American journal of cardiology. 1994 May 15:73(13):937-49 [PubMed PMID: 8184849]

Rundo F, Conoci S, Ortis A, Battiato S. An Advanced Bio-Inspired PhotoPlethysmoGraphy (PPG) and ECG Pattern Recognition System for Medical Assessment. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Jan 30:18(2):. doi: 10.3390/s18020405. Epub 2018 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 29385774]

Surawicz B, Childers R, Deal BJ, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Gorgels A, Hancock EW, Josephson M, Kligfield P, Kors JA, Macfarlane P, Mason JW, Mirvis DM, Okin P, Pahlm O, Rautaharju PM, van Herpen G, Wagner GS, Wellens H, American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part III: intraventricular conduction disturbances: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation. 2009 Mar 17:119(10):e235-40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191095. Epub 2009 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 19228822]

Spicer DE, Henderson DJ, Chaudhry B, Mohun TJ, Anderson RH. The anatomy and development of normal and abnormal coronary arteries. Cardiology in the young. 2015 Dec:25(8):1493-503. doi: 10.1017/S1047951115001390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26675596]

Padala SK, Cabrera JA, Ellenbogen KA. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE. 2021 Jan:44(1):15-25. doi: 10.1111/pace.14107. Epub 2020 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 33118629]

Klabunde RE. Cardiac electrophysiology: normal and ischemic ionic currents and the ECG. Advances in physiology education. 2017 Mar 1:41(1):29-37. doi: 10.1152/advan.00105.2016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28143820]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFakhri Y, Sejersten M, Schoos MM, Melgaard J, Graff C, Wagner GS, Clemmensen P, Kastrup J. Algorithm for the automatic computation of the modified Anderson-Wilkins acuteness score of ischemia from the pre-hospital ECG in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Journal of electrocardiology. 2017 Jan-Feb:50(1):97-101. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2016.11.005. Epub 2016 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 27889057]

Ikawa A, Asai T, Kusakawa S. New EKG changes in rheumatic carditis. Japanese circulation journal. 1979 May:43(5):476-8 [PubMed PMID: 470109]

Yilmaz S, Cakar MA, Vatan MB, Kilic H, Keser N. ECG Changes Due to Hypothermia Developed After Drowning: Case Report. Turkish journal of emergency medicine. 2014 Mar:14(1):37-40. doi: 10.5505/1304.7361.2014.60590. Epub 2016 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 27331164]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLocati ET, Bagliani G, Testoni A, Lunati M, Padeletti L. Role of Surface Electrocardiograms in Patients with Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices. Cardiac electrophysiology clinics. 2018 Jun:10(2):233-255. doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2018.02.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29784482]

Alborzi Z, Zangouri V, Paydar S, Ghahramani Z, Shafa M, Ziaeian B, Radpey MR, Amirian A, Khodaei S. Diagnosing Myocardial Contusion after Blunt Chest Trauma. The journal of Tehran Heart Center. 2016 Apr 13:11(2):49-54 [PubMed PMID: 27928254]

Saleh A, Shabana A, El Amrousy D, Zoair A. Predictive value of P-wave and QT interval dispersion in children with congenital heart disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension for the occurrence of arrhythmias. Journal of the Saudi Heart Association. 2019 Apr:31(2):57-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2018.11.006. Epub 2018 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 30618481]

El-Sherif N, Turitto G. Electrolyte disorders and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiology journal. 2011:18(3):233-45 [PubMed PMID: 21660912]

Drezner JA, Sharma S, Baggish A, Papadakis M, Wilson MG, Prutkin JM, Gerche A, Ackerman MJ, Borjesson M, Salerno JC, Asif IM, Owens DS, Chung EH, Emery MS, Froelicher VF, Heidbuchel H, Adamuz C, Asplund CA, Cohen G, Harmon KG, Marek JC, Molossi S, Niebauer J, Pelto HF, Perez MV, Riding NR, Saarel T, Schmied CM, Shipon DM, Stein R, Vetter VL, Pelliccia A, Corrado D. International criteria for electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes: Consensus statement. British journal of sports medicine. 2017 May:51(9):704-731. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097331. Epub 2017 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 28258178]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKligfield P, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Deal BJ, Hancock EW, van Herpen G, Kors JA, Macfarlane P, Mirvis DM, Pahlm O, Rautaharju P, Wagner GS, American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Rhythm Society. Recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part I: The electrocardiogram and its technology. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart rhythm. 2007 Mar:4(3):394-412 [PubMed PMID: 17341413]

Zimetbaum PJ, Josephson ME. Use of the electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Mar 6:348(10):933-40 [PubMed PMID: 12621138]

Wimmer NJ, Scirica BM, Stone PH. The clinical significance of continuous ECG (ambulatory ECG or Holter) monitoring of the ST-segment to evaluate ischemia: a review. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2013 Sep-Oct:56(2):195-202. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.07.001. Epub 2013 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 24215751]

Do DH, Hayase J, Tiecher RD, Bai Y, Hu X, Boyle NG. ECG changes on continuous telemetry preceding in-hospital cardiac arrests. Journal of electrocardiology. 2015 Nov-Dec:48(6):1062-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2015.08.001. Epub 2015 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 26362882]

Wasserlauf J, You C, Patel R, Valys A, Albert D, Passman R. Smartwatch Performance for the Detection and Quantification of Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2019 Jun:12(6):e006834. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006834. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31113234]

Francis J. ECG monitoring leads and special leads. Indian pacing and electrophysiology journal. 2016 May-Jun:16(3):92-95. doi: 10.1016/j.ipej.2016.07.003. Epub 2016 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 27788999]

Yang XL, Liu GZ, Tong YH, Yan H, Xu Z, Chen Q, Liu X, Zhang HH, Wang HB, Tan SH. The history, hotspots, and trends of electrocardiogram. Journal of geriatric cardiology : JGC. 2015 Jul:12(4):448-56. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.04.018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26345622]

Chaubey VK, Chhabra L. Spodick's sign: a helpful electrocardiographic clue to the diagnosis of acute pericarditis. The Permanente journal. 2014 Winter:18(1):e122. doi: 10.7812/TPP/14-001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24626086]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakla G, Petre JH, Doyle DJ, Horibe M, Gopakumaran B. The problem of artifacts in patient monitor data during surgery: a clinical and methodological review. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2006 Nov:103(5):1196-204 [PubMed PMID: 17056954]

Harrigan RA, Chan TC, Brady WJ. Electrocardiographic electrode misplacement, misconnection, and artifact. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2012 Dec:43(6):1038-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.024. Epub 2012 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 22929906]

Mangalmurti S, Seabury SA, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Oetgen WJ, Jena AB. Medical professional liability risk among US cardiologists. American heart journal. 2014 May:167(5):690-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.02.007. Epub 2014 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 24766979]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBecker DE. Fundamentals of electrocardiography interpretation. Anesthesia progress. 2006 Summer:53(2):53-63; quiz 64 [PubMed PMID: 16863387]

Atwood D, Wadlund DL. ECG Interpretation Using the CRISP Method: A Guide for Nurses. AORN journal. 2015 Oct:102(4):396-405; quiz 406-8. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2015.08.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26411823]

Spodick DH, Frisella M, Apiyassawat S. QRS axis validation in clinical electrocardiography. The American journal of cardiology. 2008 Jan 15:101(2):268-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.069. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18178420]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReeves WC. ECG criteria for right atrial enlargement. Archives of internal medicine. 1983 Nov:143(11):2155-6 [PubMed PMID: 6227299]

Batra MK, Khan A, Farooq F, Masood T, Karim M. Assessment of electrocardiographic criteria of left atrial enlargement. Asian cardiovascular & thoracic annals. 2018 May:26(4):273-276. doi: 10.1177/0218492318768131. Epub 2018 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 29587523]

Nikus K, Pérez-Riera AR, Konttila K, Barbosa-Barros R. Electrocardiographic recognition of right ventricular hypertrophy. Journal of electrocardiology. 2018 Jan-Feb:51(1):46-49. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.09.004. Epub 2017 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 29046220]

NOTH PH, MYERS GB, KLEIN HA. The precordial electrocardiogram in left ventricular hypertrophy; a study of autopsied cases. Proceedings [of the] annual meeting. Central Society for Clinical Research (U.S.). 1947:20():54 [PubMed PMID: 20272816]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaranchuk A, Bayés de Luna A. The P-wave morphology: what does it tell us? Herzschrittmachertherapie & Elektrophysiologie. 2015 Sep:26(3):192-9. doi: 10.1007/s00399-015-0385-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26264481]

PIPBERGER HV, TANENBAUM HL. [The P wave, P-R interval, and Q-T ratio of the normal orthogonal electrocardiogram]. Circulation. 1958 Dec:18(6):1175-80 [PubMed PMID: 13608848]

Hawks MK, Paul MLB, Malu OO. Sinus Node Dysfunction. American family physician. 2021 Aug 1:104(2):179-185 [PubMed PMID: 34383451]

Kwok CS, Rashid M, Beynon R, Barker D, Patwala A, Morley-Davies A, Satchithananda D, Nolan J, Myint PK, Buchan I, Loke YK, Mamas MA. Prolonged PR interval, first-degree heart block and adverse cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2016 May:102(9):672-80. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308956. Epub 2016 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 26879241]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAro AL, Anttonen O, Kerola T, Junttila MJ, Tikkanen JT, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, Huikuri HV. Prognostic significance of prolonged PR interval in the general population. European heart journal. 2014 Jan:35(2):123-9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht176. Epub 2013 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 23677846]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceClark BA, Prystowsky EN. Electrocardiography of Atrioventricular Block. Cardiac electrophysiology clinics. 2021 Dec:13(4):599-605. doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2021.07.001. Epub 2021 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 34689889]

Lim Y, Singh D, Poh KK. High-grade atrioventricular block. Singapore medical journal. 2018 Jul:59(7):346-350. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2018086. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30109349]

Alnsasra H, Ben-Avraham B, Gottlieb S, Ben-Avraham M, Kronowski R, Iakobishvili Z, Goldenberg I, Strasberg B, Haim M. High-grade atrioventricular block in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Insights from a contemporary multi-center survey. Journal of electrocardiology. 2018 May-Jun:51(3):386-391. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2018.03.003. Epub 2018 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 29550105]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmiseth OA, Aalen JM. Mechanism of harm from left bundle branch block. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2019 Aug:29(6):335-342. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.10.012. Epub 2018 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 30401603]

Delewi R, Ijff G, van de Hoef TP, Hirsch A, Robbers LF, Nijveldt R, van der Laan AM, van der Vleuten PA, Lucas C, Tijssen JG, van Rossum AC, Zijlstra F, Piek JJ. Pathological Q waves in myocardial infarction in patients treated by primary PCI. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2013 Mar:6(3):324-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.08.018. Epub 2013 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 23433932]

Zema MJ, Kligfield P. ECG poor R-wave progression: review and synthesis. Archives of internal medicine. 1982 Jun:142(6):1145-8 [PubMed PMID: 6212033]

Channer K, Morris F. ABC of clinical electrocardiography: Myocardial ischaemia. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2002 Apr 27:324(7344):1023-6 [PubMed PMID: 11976247]

Brady WJ. ST segment and T wave abnormalities not caused by acute coronary syndromes. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2006 Feb:24(1):91-111, vi [PubMed PMID: 16308114]

de Bliek EC. ST elevation: Differential diagnosis and caveats. A comprehensive review to help distinguish ST elevation myocardial infarction from nonischemic etiologies of ST elevation. Turkish journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Mar:18(1):1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.tjem.2018.01.008. Epub 2018 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 29942875]

Chhabra L, Spodick DH. Brugada pattern masquerading as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in flecainide toxicity. Indian heart journal. 2012 Jul-Aug:64(4):404-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2012.06.010. Epub 2012 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 22929826]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhalid N, Chhabra L, Kluger J. PYREXIA-INDUCED BRUGADA PHENOCOPY. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC. 2015 Jan-Mar:27(1):228-31 [PubMed PMID: 26182783]

Chhabra L, Spodick DH. Electrocardiography in pericarditis and ST-elevation myocardial infarction: timing of observation is critical. The American journal of medicine. 2014 May:127(5):e17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24758877]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChhabra L, Chaubey VK, Spodick DH. Diagnostic criteria for acute pericarditis need closer attention. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE. 2014 May:37(5):658. doi: 10.1111/pace.12377. Epub 2014 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 24628079]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChhabra L, Spodick DH. Persistent J-ST elevation: a sign of persistent perimyocardial irritation. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2014 Aug:100(16):1301. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306079. Epub 2014 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 24829368]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChhabra L, Mujtaba M, Spodick DH. Regional pericarditis or an alternate diagnosis? Case reports in medicine. 2014:2014():313607. doi: 10.1155/2014/313607. Epub 2014 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 25053949]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChhabra L, Spodick DH. Ideal isoelectric reference segment in pericarditis: a suggested approach to a commonly prevailing clinical misconception. Cardiology. 2012:122(4):210-2. doi: 10.1159/000339758. Epub 2012 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 22890314]

Morris NP, Body R. The De Winter ECG pattern: morphology and accuracy for diagnosing acute coronary occlusion: systematic review. European journal of emergency medicine : official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 2017 Aug:24(4):236-242. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000463. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28362646]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOkin PM, Devereux RB, Kors JA, van Herpen G, Crow RS, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV. Computerized ST depression analysis improves prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: the strong heart study. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2001 Apr:6(2):107-16 [PubMed PMID: 11333167]

Tse G,Chan YW,Keung W,Yan BP, Electrophysiological mechanisms of long and short QT syndromes. International journal of cardiology. Heart [PubMed PMID: 28382321]

Rudic B, Schimpf R, Borggrefe M. Short QT Syndrome - Review of Diagnosis and Treatment. Arrhythmia & electrophysiology review. 2014 Aug:3(2):76-9. doi: 10.15420/aer.2014.3.2.76. Epub 2014 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 26835070]

Levis JT. ECG Diagnosis: Hypothermia. The Permanente journal. 2010 Fall:14(3):73 [PubMed PMID: 20844708]

Wang J, Yang B, Chen H, Ju W, Chen K, Zhang F, Cao K, Chen M. Epsilon waves detected by various electrocardiographic recording methods: in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2010:37(4):405-11 [PubMed PMID: 20844612]

Jacob L. Nurse-led clinics for atrial fibrillation: managing risk factors. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing). 2017 Dec 14:26(22):1245-1248. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2017.26.22.1245. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29240471]

Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, Kaufman ES, Krucoff MW, Laks MM, Macfarlane PW, Sommargren C, Swiryn S, Van Hare GF, American Heart Association, Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004 Oct 26:110(17):2721-46 [PubMed PMID: 15505110]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQuinn T. The role of nurses in improving emergency cardiac care. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 2005 Aug 10-16:19(48):41-8 [PubMed PMID: 16117268]

Adams TL, Orchard C, Houghton P, Ogrin R. The metamorphosis of a collaborative team: from creation to operation. Journal of interprofessional care. 2014 Jul:28(4):339-44. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.891571. Epub 2014 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 24593331]

Funk M, Fennie KP, Stephens KE, May JL, Winkler CG, Drew BJ, PULSE Site Investigators. Association of Implementation of Practice Standards for Electrocardiographic Monitoring With Nurses' Knowledge, Quality of Care, and Patient Outcomes: Findings From the Practical Use of the Latest Standards of Electrocardiography (PULSE) Trial. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2017 Feb:10(2):. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003132. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28174175]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTootill DM. Thrombolytic therapy: nursing strategies for successful patient outcomes. Progress in cardiovascular nursing. 1995 Winter:10(1):3-12 [PubMed PMID: 7770439]