Introduction

Lipomas are benign tumors of fat cells (adipocytes) that present as soft, painless masses most commonly seen on the trunk, but can be located anywhere on the body. [1][2][3] Lipomas usually range from 1- >10 cm. They are mesenchymal tumors and are found anywhere in the body where normal fat cells are present. They are benign and have many histologic subtypes. The presence of multiple lipomas may be the presenting feature of a variety of syndromes.[4] Although lipomas are present in subcutaneous planes, they may also involve fascia or deeper muscular planes in some instances.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Lipomas represent the most common mesenchymal tumors of the human body. About 1 in every thousand persons will have lipoma at some point in their lifetime. The majority of lipomas affect the trunk and upper extremity, but they can be anywhere on the body where adipocytes are present. The precise cause of lipomas is unknown. A potential link between trauma and lipoma formation has been postulated, hypothesizing trauma induces cytokine release that then triggers preadipocyte differentiation and maturation.[5]

Genetics may play a role in a minority of patients, as 2% to 3% of affected patients have multiple lesions inherited in a familial pattern.[6] An gene association has been described on chromosome 12 in some solitary lipomas; a mutation in the HMGA2-LPP fusion gene is present in some of these tumors.[7] There also are several genetic syndromes that feature lipomas as a clinical manifestation. The incidence of lipomas is also increased in patients with obesity, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus.

Epidemiology

Lipomas have a slightly higher incidence in males compared to females. Although they can occur at any age, they are often noted between the fourth to sixth decades of life. Despite being one of the most common neoplasms in humans, the incidence and prevalence of lipomas have not been reported in the literature.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of lipomas is unclear. However, benign lipomas can be present in almost any organ of the body. Subcutaneous lipomas are not usually fixed to the underlying fascia. That's why the fibrous capsule should be removed completely to prevent ist reoccurrence.

In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the lipomas present as submucosal fatty tumors. The most common locations include small intestines, stomach, and esophagus. Gastrointestinal lipomas become symptomatic only after luminal abstraction or bleeding. Mucosal erosion over lipoma may cause severe bleeding in the bowel.[8] Small bowel lipomas mostly occur in the elderly population and most commonly present in the ileum. They are usually pedunculated, submucosal lesions, and can obstruct the lumen of the bowel. [9][10] They can cause obstructive jaundice, pain, gastric outlet obstruction, and intussusception in younger patients.

Colonic lipomas are usually discovered incidentally on colonoscopy. A biopsy specimen of the lipoma will most likely reveal a mature adipocyte, which is called the "naked fat' sign. As with other lipomas, colonic lipomas can also cause pain with obstruction or intussusception.

However, several cytogenetic abnormalities have been identified, including the following:

- Mutations in chromosome 12q13-15, 65% of cases

- Deletions of 13q (10% of cases), rearrangements of 6p21-33, 5% of cases

- Unidentified mutations or normal karyotype, 15% to 20% of cases

Rearrangements of the 12q13-15 result in the fusion of the high-mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2) gene to a variety of transcription regulatory domains that promote tumorigenesis.[11][12]

Histopathology

Histologic examination of lipomas reveals mature, normal-appearing adipocytes with a small eccentric nucleus. Adipocytes are intermixed among thin fibrous septa containing blood vessels. These features are indistinguishable from adipocytes in the subcutaneous tissue. Histologic subtypes of lipomas include angiolipomas, myelolipomas, angiomyolipomas, myelolipomas, fibrolipomas, ossifying lipoma, hibernomas, spindle cell lipomas, pleomorphic lipomas, chondroid lipomas, and neural fibrolipomas. Common lipomas and their variants must be distinguished from liposarcomas, which are a malignant lipomatous neoplasm containing lipoblasts, which are characterized by coarse vacuoles and one or more scalloped, hyperchromatic nuclei.[13]

History and Physical

Lipomas typically present as soft, solitary, painless, subcutaneous nodules that are mobile and not associated with epidermal change. A characteristic "slippage sign" may be elicited by gently sliding the fingers off the edge of the tumor. They are typically slow-growing and may grow to a final stable size. However, they are occasionally greater than 10 centimeters and referred to as "giant lipomas." Lipomas may appear anywhere on the body but tend to favor the fatty areas of the trunk, neck, forearms, and proximal extremities. They are rarely seen in acral areas. Lipomas may affect many cutaneous and noncutaneous sites, including dermal, subcutaneous, and subfascial tissues along with intermuscular, intramuscular, synovial, bone, nervous, or retroperitoneal sites.

Multiple lipomas are present in 5% to 10% of affected patients and are usually associated with familial lipomatosis or numerous other genetic disorders described in the differential diagnosis section. The use of protease inhibitors in HIV patients may induce lipomas and lipodystrophy; therefore, a thorough past medical and medication history should be obtained.

Signs and symptoms of lipomas depend largely on the location and size of the lipomas. It can cause respiratory distress related to bronchial obstruction; patients may present with either endobronchial or parenchymal. Cardiac lipomas are located mainly subendocardial, are rarely found intramurally, and are normally unencapsulated; they appear as a yellow mass projecting into the cardiac chamber lesions. Patients with esophageal lipomas can present with obstruction, dysphagia, regurgitation, vomiting, and reflux; esophageal lipomas can be associated with aspiration and consecutive respiratory infections.

Evaluation

Common lipomas frequently are diagnosed clinically and are sent for histologic examination after complete surgical excision.[14] Radiologic imaging before surgery may be prudent in cases featuring the following:

- Giant size (greater than 10 centimeters),

- Rapid growth

- Pain

- Fixation to underlying tissues

- Location in deep tissues, the thigh, or retroperitoneal space

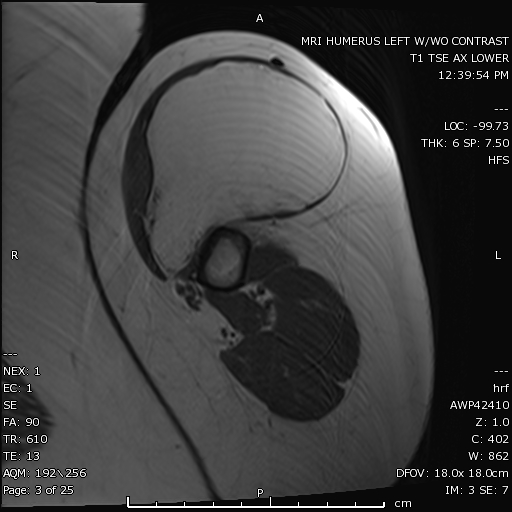

For most subcutaneous lipomas, no imaging studies are required. However, lesions in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract may be visible on GI contrast studies, While imaging like ultrasound, MRI, and CT scans is required for lipomas an atypical location.[15] As lipomas are radiolucent, soft tissue radiography can be diagnostic, but it is only employed when the diagnosis is in doubt clinically.

Treatment / Management

The majority of the patients who seek treatment for lipomas are due to cosmetic reasons. Lipomas do not involute spontaneously, although dramatic weight loss may make lesions more clinically prominent as they may not regress at the same rate as normal adipose tissue. Stable lesions often are observed clinically. The decision to treat depends on numerous factors, including lesion size, anatomic location, symptoms such as pain, and patient comorbidities. If treatment is desired, surgical excision is commonly employed. Large lipomas have been removed via liposuction.[16][17][18]

Therapies such as endoscopy and colonoscopy are utilized for the lipomas of the gastrointestinal tract (GI). Colonoscopic removal of lipomas is associated with a higher risk of colon perforation.

Complete surgical excision of the capsule is recommended. Intracardiac lipomas are usually lobulated, and all lobules must be removed for a better outcome. Subcutaneous lipomas are removed for cosmetic reasons. Therefore a cosmetically pleasing incision should be used. The incision is usually placed directly over the mass in a line of skin tension. Local removal is indicated in intestinal lipomas, causing obstruction and hemorrhage; the uncertainty of diagnosis for an intramural intestinal mass also warrants resection. If esophageal lipomas can not be endoscopically removed, surgical excision is indicated, whether by a transhiatal or a transthoracic approach.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes but is not limited to epidermoid cysts, hibernomas, angiolipomas, angiomyolipomas, and liposarcomas. Epidermoid cysts typically feature a punctum at their surface; however, lesions lacking this feature may be indistinguishable from lipomas. Hibernomas are benign, rare, slow-growing masses of brown fat that typically occur in the mediastinum or interscapular region of the back and present as a 3 to 12 centimeter, slow-growing mass in an adult. Angiolipomas are often painful, less than 2 centimeters in width, well-circumscribed, and typically appearing on the forearm of teens or young adults. Angiomyolipomas often present in acral locations of adult males. Liposarcomas most commonly present as deep-seated tumors in the retroperitoneum or, classically, on the thighs.

Multiple lipomas can be a manifestation of the following syndromes:

- Proteus syndrome due to activating mutations in AKT1 oncogene (or occasionally PTEN mutations). It consists of lipomas, epidermal nevi, hemangiomas, palmoplantar cerebriform connective tissue nevi, hyperostoses of the epiphyses and skull, and scoliosis.

- Dercum disease (adiposis dolorosa) consists of multiple painful lipomas on the trunk and extremities, which often have overlying paresthesias of the skin. It is often seen in postmenopausal women. Some patients with this diagnosis also have psychiatric disorders.

- Familial multiple lipomatosis- patients typically present in the '30s with hundreds of encapsulated and noninfiltrating lipomas. It can be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

- Benign symmetric lipomatosis (Madelung disease) involves diffuse, infiltrative, symmetric painless lipomatous growths affecting the head, neck, and shoulder region. Middle-aged alcoholic men are usually present with this syndrome. Mutations in the mitochondrial tRNA lysine gene have been identified in a few of the affected patients.

- Gardner syndrome is due to autosomal dominant mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. Almost all patients develop adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Cutaneous changes include multiple lipomas or fibromas. Other associated findings include congenital hypertrophy of pigment epithelium of the retina, osteomas of the skull, maxilla and mandible, supernumerary teeth, and various malignancies, including papillary thyroid carcinomas, adrenal adenomas, and hepatoblastomas.

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1 is due to autosomal dominant mutations in the MEN1 gene. It consists of parathyroid, pituitary, and pancreatic tumors. Dermatologic changes include multiple lipomas (which may also occur in visceral sites), collagenomas, angiofibromas, and cafe au lait macules.

- Cowden syndrome is due to mutations in the PTEN gene. It is associated with multiple lipomas, oral papillomas, facial trichilemmomas, punctate palmoplantar keratoses, and malignancies, including breast adenocarcinoma, thyroid follicular carcinoma (TFC), endometrial carcinomas, and hamartomatous polyps of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome (BRRS) is also due to PTEN gene mutations and may represent a pediatric form of Cowden syndrome. Clinical findings include multiple lipomas, intestinal hamartomas, genital lentigines, macrocephaly, and mental retardation.

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent for benign lipomas. Recurrence is not common but may develop if the excision was incomplete.

Complications

Gastrointestinal lipomas can cause obstructive symptoms and bleed secondary to ulceration. Cardiac lipomas may cause embolism if they interfere with the anatomy of the cardiac chamber. Although rare but local lipomas may cause nerve compression. As these lipomas enlarge, they can compress the adjacent nerves and local structure. The majority of lipomas have a benign course and do not recur after surgical removal. It is advisable to completely excise the capsule to minimize the risk of reoccurrence.

Consultations

Lipomatous lesions arising in the midline sacrococcygeal region can be a manifestation of spinal dysraphism (along with skin tags, hair tufts, angiomas, and a variety of other cutaneous changes). For this reason, a neurosurgery consultation is indicated for lipomatous lesions in this region.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lipomas are commonly encountered by the primary care provider and nurse practitioner. However, definitive management is usually done by a dermatologist, general surgeon, or plastic surgeon. There are many ways to treat lipomas, but asymptomatic lesions should be left alone. Lipomas usually incur minimal morbidity- which in most cases is poor cosmesis.[19] an interprofessional team approach is best with a primary care provider, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant providing follow-up and communication to the surgeon as needed.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tong KN, Seltzer S, Castle JT. Lipoma of the Parotid Gland. Head and neck pathology. 2020 Mar:14(1):220-223. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01023-3. Epub 2019 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 30888640]

Demicco EG. Molecular updates in adipocytic neoplasms(✰). Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2019 Mar:36(2):85-94. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2019.02.003. Epub 2019 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 30857767]

Creytens D. A contemporary review of myxoid adipocytic tumors. Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2019 Mar:36(2):129-141. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2019.02.008. Epub 2019 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 30853315]

Putra J, Al-Ibraheemi A. Adipocytic tumors in Children: A contemporary review. Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2019 Mar:36(2):95-104. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2019.02.004. Epub 2019 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 30850231]

Aust MC, Spies M, Kall S, Jokuszies A, Gohritz A, Vogt P. Posttraumatic lipoma: fact or fiction? Skinmed. 2007 Nov-Dec:6(6):266-70 [PubMed PMID: 17975353]

Barisella M, Giannini L, Piazza C. From head and neck lipoma to liposarcoma: a wide spectrum of differential diagnoses and their therapeutic implications. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2020 Apr:28(2):136-143. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000608. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32011399]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePanagopoulos I, Gorunova L, Agostini A, Lobmaier I, Bjerkehagen B, Heim S. Fusion of the HMGA2 and C9orf92 genes in myolipoma with t(9;12)(p22;q14). Diagnostic pathology. 2016 Feb 9:11():22. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0472-8. Epub 2016 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 26857357]

Yoshii H, Izumi H, Tajiri T, Mukai M, Nomura E, Makuuchi H. Surgical Resection for Hemorrhagic Duodenal Lipoma: A Case Report. The Tokai journal of experimental and clinical medicine. 2020 Jul 20:45(2):75-80 [PubMed PMID: 32602105]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePintor-Tortolero J, Martínez-Núñez S, Tallón-Aguilar L, Padillo-Ruiz FJ. Colonic intussusception caused by giant lipoma: a rare cause of bowel obstruction. International journal of colorectal disease. 2020 Oct:35(10):1973-1977. doi: 10.1007/s00384-020-03629-4. Epub 2020 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 32542410]

Tjandra D, Knowles B, Simkin P, Kranz S, Metz A. Duodenal Lipoma Causing Intussusception and Gastric Outlet Obstruction. ACG case reports journal. 2019 Nov:6(11):e00157. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000157. Epub 2019 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 32309462]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurkes JN, Campos L, Williams FC, Kim RY. Laryngeal Spindle Cell/Pleomorphic Lipoma: A Case Report. An In-Depth Review of the Adipocytic Tumors. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2019 Jul:77(7):1401-1410. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2019.01.050. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30826392]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChrisinger JSA. Update on Lipomatous Tumors with Emphasis on Emerging Entities, Unusual Anatomic Sites, and Variant Histologic Patterns. Surgical pathology clinics. 2019 Mar:12(1):21-33. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2018.11.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30709444]

Forcucci JA, Sugianto JZ, Wolff DJ, Maize JC Sr, Ralston JS. "Low-Fat" Pseudoangiomatous Spindle Cell Lipoma: A Rare Variant With Loss of 13q14 Region. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2015 Dec:37(12):920-3. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000286. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25839893]

Lichon S, Khachemoune A. Clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and treatment of hand lipomas: a review. Acta dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica, et Adriatica. 2018 Sep:27(3):137-139 [PubMed PMID: 30244263]

Gryglewski A, Wantuch K, Wójciak S, Opach Z, Richter P. Pre-operative ultrasound diagnosis and successful surgery of a stomach incarcerated in epigastric hernia: a rare case report. Folia medica Cracoviensia. 2020:60(1):55-60 [PubMed PMID: 32658212]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson CN,Ha AS,Chen E,Davidson D, Lipomatous Soft-tissue Tumors. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018 Nov 15; [PubMed PMID: 30192249]

Datir A, James SL, Ali K, Lee J, Ahmad M, Saifuddin A. MRI of soft-tissue masses: the relationship between lesion size, depth, and diagnosis. Clinical radiology. 2008 Apr:63(4):373-8; discussion 379-80. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.08.016. Epub 2007 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 18325355]

Drylewicz MR, Lubner MG, Pickhardt PJ, Menias CO, Mellnick VM. Fatty masses of the abdomen and pelvis and their complications. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2019 Apr:44(4):1535-1553. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1784-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30276422]

Najaf Y, Cartier C, Favier V, Garrel R. Symptomatic head and neck lipomas. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2019 Apr:136(2):127-129. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2018.12.001. Epub 2018 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 30606653]