Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in women, after skin cancer, and represents 14% of all new cancers in the United States.[1] Breast cancer is most commonly diagnosed in women aged 55 to 64 years, and the risk increases with age.[2] Early diagnosis increases the chances that a patient may achieve a cure and also reduces the morbidity of the treatments. Breast cancer therapies continue to improve and have contributed to mortality reduction, but early diagnosis through mammographic screening has had a greater overall impact on mortality reductions.[3] The American College of Radiology recommends breast cancer screening for all average-risk women starting at the age of 40.[4] The diagnosis of breast cancer can be suggested by many different modalities, most commonly mammography, breast ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

However, tissue sampling is required for a definitive diagnosis. Breast cancer screening is performed with mammography, and patients with equivocal or suggestive mammographic screening results require further imaging with a diagnostic mammogram, ultrasound, breast MRI, biopsy, or combination thereof. This article will discuss the techniques and considerations when performing screening breast mammography.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The breast is composed of fat and fibroglandular tissue, with the breast parenchyma being composed of a vibrant network of exocrine glands, ducts, stromal connective tissues, vasculature, and nerves. This tissue extends from the second through sixth ribs and is bordered by the sternum and the midaxillary line. The breast tissue is commonly divided into quadrants for ease of localization. This is performed by segmenting the breast into medial/lateral and upper/lower components using the nipple as a reference point. It should be noted that the upper outer quadrants of the breasts often contain breast tissue that extends into the axilla. This is relevant for mammographic technique, as this region of breast tissue may be difficult to image fully without adequate patient positioning. Furthermore, one of the primary lymphatic drainage networks of the breast passes through the axilla, and abnormal lymph nodes may be incidentally discovered by imaging this region.

Mammography can be used to evaluate the breast based on the differential attenuation characteristics of the tissues. Specifically, fat attenuates fewer x-rays than fibroglandular tissue and stromal elements and appears gray on mammography. Dense mineral deposits can be easily identified and appear bright white, such as skin calcifications or calcifications within a neoplastic lesion. Superimposition poses a challenge in mammography, as tissue structures that overlie or overlap one another may obscure a small mass. To try and combat this, screening mammograms are performed in at least two standard views, which include the craniocaudal view (CC) and the mediolateral oblique (MLO). By comparing these two different viewpoints, structures that are superimposed upon one another in one view may be separated in the other. In cases of uncertainty, additional diagnostic views with spot compression paddles or variant angles, such as a mediolateral (ML) view, may be obtained. Additionally, newer technologies such as tomosynthesis imaging allow the radiologist to scroll through the breast in slices, decreasing the superimposition effect of tissues. A typical mammogram can depict the skin surface, the nipple, the main breast ducts, fibroglandular tissue, veins, adipose tissue, muscle, and occasionally lymph nodes.

The relative abundance of fibroglandular tissue versus fat that a patient has in their breast can vary considerably from person to person, and even within the same patient depending on hormonal factors and weight changes. For example, the hormonal effects of pregnancy and lactation can increase the abundance of glandular tissue, and similarly, cessation of lactation causes fibroglandular tissue to regress. Dense breast tissue attenuates a higher proportion of x-rays and appears whiter on a mammogram and may pose a diagnostic challenge when trying to detect breast cancer due to the masking effect. This is further complicated by the fact that patients with dense breast tissue are at increased risk of developing breast cancer.[5] As such, great care must be taken when imaging patients with dense breast tissue, and if extremely dense breast tissue limits screening mammography, supplemental evaluation with breast ultrasound or MRI may be considered.

Every screening mammogram is evaluated to ensure the technical quality, including adequate positioning as breast cancers may be missed if not enough tissue is imaged. The breast tissue overlies the pectoralis major muscles, and these muscles can be partially seen on mammographic images. The pectoralis demonstrates a striated appearance on the MLO view that is denser than the overlying fat and fibroglandular tissue. As a rule of thumb, the MLO view is not adequate if the pectoralis is not intersected by a line drawn orthogonally from the nipple posteriorly, also known as the posterior-nipple line (PNL). The CC view is not adequate if the PNL is not within 1 cm of the MLO posterior-nipple line.

Indications

Several professional societies offer recommendations on breast cancer screening. They include the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American College of Radiology, the Society for Breast Imaging, the American Cancer Society, the American Medical Association, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the United States Preventative Service Task Force (USPSTF).[6][7][8][4][9] An in-depth discussion of the differences in the recommendations between these professional societies is beyond the scope of this article. According to the American College of Radiology, annual mammographic screening is recommended beginning at age 40 for all women with an average risk of developing breast cancer and should continue for women with a life expectancy of at least 5 to 7 years as long as the patient is willing to undergo further testing/biopsy and treatment. Specifically, there is no age cutoff for when screening mammography should be discontinued. Instead, a patient's health status should dictate whether screening measures continue to be warranted. Although breast cancer is most commonly diagnosed in the 50 to 60 age range, risk increases with age and screening mammography offer an opportunity to detect early malignant lesions or even precancerous lesions before they become otherwise clinically evident. Average risk patients are those with less than a 15% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer.[10]

Patients with an increased risk of developing breast cancer require special consideration since they may develop breast cancer at an earlier age or require supplemental screening modalities beyond routine mammograms. Patients are considered to have an intermediate risk or 15% to 20% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer if they have any of the following:

- Personal history of breast cancer

- Atypical ductal hyperplasia on a prior breast biopsy

- Lobular neoplasia on a prior breast biopsy

Patients with intermediate-risk should receive a screening mammogram annually and may benefit from supplemental screening with breast ultrasound and possibly breast MRI. Ultrasound is particularly useful in the setting of dense breast fibroglandular tissue, as a high-quality ultrasound examination is not impeded by increased breast density.[11]

Finally, patients with a 20% or higher lifetime risk of developing breast cancer are considered high-risk. In addition to supplemental screening modalities, these patients also benefit from initiating breast cancer screening at a younger age. High-risk patients are those with the following:

- Women with specific gene mutations, including BRCA 1 and 2.

- Those with a strong family history of breast cancer, even in the absence of a known gene mutation.

- Patients that have received radiation therapy of the chest between 10 to 30 years of age.

Patients with a family history of breast cancer should begin screening mammography ten years before the age at which the youngest first-degree relative developed breast cancer; however, with the caveat that these patients should not start screening before the age of 30, as there are concerns that these patients may have an increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation, which mammography relies upon.[4] In addition to mammography, screening breast MRI is recommended for these patients, given its increased sensitivity.[12]

It is recommended that women undergo a risk assessment by age 30 to determine the appropriate screening timeline. Screening mammography is not recommended for male patients with breast tissue, known as gynecomastia.

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to screening mammography, but relative contraindications do exist. First, any woman with signs or symptoms that are concerning for breast cancer, such as the presence of a palpable or enlarging breast mass, should undergo diagnostic mammographic and sonographic imaging rather than screening imaging alone. The distinction between screening and diagnostic mammography is made by the ability to utilize additional imaging techniques, which may include spot compression, supplementary angles, or magnification views. Diagnostic breast ultrasound adds complementary information, particularly when concerning lesions are identified through palpation.

As described above, for asymptomatic patients with an average risk of developing breast cancer, screening mammography is not recommended before the age of 40. Patients of this age group generally have increased breast density and mammography has decreased sensitivity for detecting breast cancer in this setting. There is also a risk of false-positive mammographic findings, potentially necessitating follow-up imaging, and possibly a tissue biopsy.[13] However, it is recommended that all women undergo risk assessment at age 30 to see if earlier screening is appropriate.

Mammography utilizes X-ray radiation to generate diagnostic images, a form of ionizing radiation. The X-rays used in mammography are lower energy than those used in CT or plain radiography, but there are at least theoretical risks with any degree of ionizing radiation exposure.[14] Thus, patients who are pregnant or who are lactating deserve special consideration. The radiation dose to the fetus during pregnancy is negligible and is well below the known thresholds for adverse pregnancy outcomes;[15] however, mammography should be tailored to the individual patient needs. When possible, dose-reduction techniques should be employed. Pregnancy should not preclude the evaluation of suspected pregnancy-associated breast cancer, but screening mammography may be deferred until the end of pregnancy for asymptomatic patients at average risk of developing breast cancer.[16]

Patients that are lactating deserve additional considerations, as the milk-producing lobules attenuate more X-rays, increasing the breast tissue density and potentially obscuring premalignant or malignant lesions. However, breastfeeding or pumping before the study may decrease breast parenchymal density and increase the sensitivity of mammography.[17] Thus, lactation does not contraindicate screening mammography, but patients should be given advance guidance before any imaging exams.[16]

Equipment

As briefly described previously, mammography utilizes x-rays to evaluate the different anatomic structures within the breast. Initially, mammograms were performed using traditional film-based radiographic techniques. However, film mammography has been replaced by systems that use phosphor storage technology or direct digital capture. The phosphor storage systems use a crystal that transforms x-rays into visible light, which is subsequently digitized. The direct digital capture systems utilize a CCD array that can directly transfer the x-ray into a digital image. There are many advantages to these newer technologies over film mammography, most notably, the dynamic range and contrast resolution can be adjusted after image capture; this allows radiologists to assess subtle differences within tissues better and optimize image rendering at the workstation.[18]

Recently, digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT, also known as "3D mammography") has gained popularity. Briefly, DBT is performed by obtaining multiple mammographic projections per view, and these projections are acquired serially along an arc. The images are then reconstructed via post-processing techniques into a series of stacked images of 1mm slice thickness. The image stacks combat the challenges of superimposed tissues seen in single-projection mammography by allowing the breast to be assessed in the X, Y, and Z dimensions.[19] DBT has been shown to increase cancer detection and decrease false-positive rates. Furthermore, this increased sensitivity offers the chance to identify lower grade cancers, thereby improving treatment options and prognosis. Given these advantages, the use of DBT in both screening and diagnostic mammography is rapidly becoming the standard of care.[20]

The essential mammography components include an x-ray generator, an image detector, and a breast compression paddle. The x-ray generator and image detector are set at a fixed distance and are oriented orthogonally to one another, but the entire unit can be rotated to obtain the required mammographic views. Additional protective equipment is necessary for the technical personnel who take the mammograms; this includes a protective shield with a remote control station to operate the equipment.

Personnel

Screening and diagnostic mammography require several key personnel. First, the radiology technologist is chiefly responsible for imaging equipment setup, patient positioning, and image acquisition. Second, medical physicists are needed to ensure the quality and accuracy of the mammography equipment and image generation.[21][22] With the widespread adoption of digital mammography, an information technology team is essential to assure the infrastructure for image transmission, data storage, and display. Finally, the diagnostic radiologist is needed to interpret the mammographic images and to confirm quality mammographic examinations. All personnel must meet the minimum training requirements as set forth by the Mammography Quality Standards Act.[23]

Preparation

Mammography equipment must be appropriately calibrated and checked for deficiencies. These quality control tests can be performed by a radiology technologist, and the medical physicist can assist in recalibration if issues arise.[23] On arrival, the patient's identity should be verified, and they should be fully informed about the steps in mammography. The patient’s family, medical and surgical histories should be reviewed to allow adequate personal breast cancer risk stratification. Specifically, the patient should be screened for any family history of breast cancer, any breast-related changes (e.g., the development of palpable lumps, tenderness or skin changes), or prior surgical intervention (e.g., breast augmentation or mammoplasty, needle/surgical biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection). The patient should take any upper-body clothing off and be given a robe. Any raised skin lesions such as moles or scars from prior surgical interventions should be marked with radiopaque skin markers, allowing for easy identification and reducing callbacks related to misinterpretation as masses or suspicious architectural distortion. Finally, the technologist should enter the patient's information into the mammography equipment before beginning the exam.

Technique or Treatment

There are two standard views in screening mammography, named for the direction of the x-ray beam from the source to detector: craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO).

For the CC view, the patient's breast is positioned on the image detector with the paddle compressing the breast in the superior-inferior direction. There should be at least some of the inframammary tissues present on the detector, and the image should ideally include the cleavage area and some of the pectoralis major muscle (seen in approximately 30%). These landmarks help to ensure that adequate tissue is imaged, as not to exclude a portion of breast tissue that may harbor a malignant lesion. Compression is adjusted, taking into account multiple factors, including breast size and patient tolerance. Without adequate compression, there may be an inadequate separation of the parenchymal tissues, nonuniform exposure throughout the breast, increased dose, and a greater likelihood for motion. No portion of the breast should be cut off or excluded from the field of view.

For the MLO view, the machine is angled generally 40 to 60 degrees. In routine screening, this is preferred over a true lateral because the axillary tail and axilla are included. The breast is similarly applied to the image detector, again covering as much of the breast tissues as possible, including the inframammary fold and as much posterior tissue as possible. A line drawn from the nipple to the chest wall should be within 1cm of the same line drawn on the CC view to ensuring the comparability of the different images. It is essential to try and include as much of the breast tissue that is within the axillary tail, as breast cancers may develop in this region.

If diagnostic mammographic images are necessary, focal compression or magnification paddles may be needed to further assess masses/asymmetries or calcifications. The focal compression paddle is placed by estimating the location of the lesion based on the screening mammogram images. Magnification views may be performed by lifting the breast away from the image detector, allowing for geometric magnification. Findings are described by location using a clock-face and distance from the nipple (in centimeters).

Complications

Screening mammography is well tolerated with few complications. Both immediate and subacute complications could arise from excessive breast compression. These are limited to bruising, small hematomas, and the temporary discomfort that occurs from compression. Inadequate imaging is an additional complication that can be avoided through careful positioning and technique.

Clinical Significance

Mammography is currently the gold standard screening tool for breast cancer and has been shown to decrease breast cancer mortality and reduce treatment morbidity; however, mammography is far from perfect. Screening mammography can miss nearly a quarter of cancers that become discovered clinically within one year.[24] Quality mammographic exams are both equipment and technique dependent, and regulatory standards are higher within this single modality than nearly any other radiologic specialty.[23] A complete understanding of the indications, procedures, and pitfalls is essential to deliver high-quality care to patients at risk of developing breast cancer.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Quality assurance is a significant concern within the field of mammography, and a team approach is essential for navigating the complexities of patient care. Morbidity and mortality reduction is dependent on early identification of malignant lesions on mammography. This depends not only on the chain of events from image preparation, acquisition to interpretation but also critically includes patient communication. Identifying high-risk lesions is of no clinical benefit if the patient is not promptly notified and engaged with adequate services and healthcare specialists. As such, an interprofessional team approach to breast cancer management affords the most significant benefit for clinical care.

Patients with abnormal or concerning results should be promptly notified of the results and given clear direction on the necessary follow-up care. Once a lesion is identified, the patient requires additional imaging with diagnostic mammography and/or ultrasound. For patients with findings concerning for malignancy, a breast biopsy is necessary. Coordinating these steps requires a comprehensive breast imaging team. Radiologists identify the lesions initially and notify the clinical support staff of the results. These support staffs are tasked with reaching out to the patients and the referring provider with the results and suggested course of action. Once further diagnostic imaging and biopsy are performed, coordination with pathology is required, and the results must be communicated directly to the patients. Finally, if a high-risk or malignant lesion is identified, the patient is referred for surgical oncology consultation, and often the case is discussed in an interprofessional meeting that includes medical oncologists, radiologic oncologists, breast surgeons, pathologists, radiologists, genetic counselors, and nurse navigators. The cycle from identifying a concerning lesion on mammography to the diagnosis of breast cancer should take no longer than approximately three months.[25]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Interprofessional teams play a vital role in providing exceptional breast care and communicating mammographic results. At the center of the group are the radiology technologists. These professionals play a crucial role by serving as problem-solvers in obtaining not only technically adequate but optimal mammographic images. Useful diagnostic information can be obtained from the patient during mammographic image acquisition and correlated to image findings. Close-knit communication between radiology technologists and diagnostic radiologists is essential for quality assurance and contextual understanding.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Nurses and care coordinators are fundamental members of the breast imaging team, as they help ensure follow-up care for patients. As in all areas of medicine, access to care can be limited for many reasons and poses a significant threat to screening mammography. Patients with urgent or critical mammography results should be tracked, and follow-up care should not just be recommended but ensured. Care coordinators and nursing staff may communicate key results, verify follow-up appointments, and provide adequate care is received.

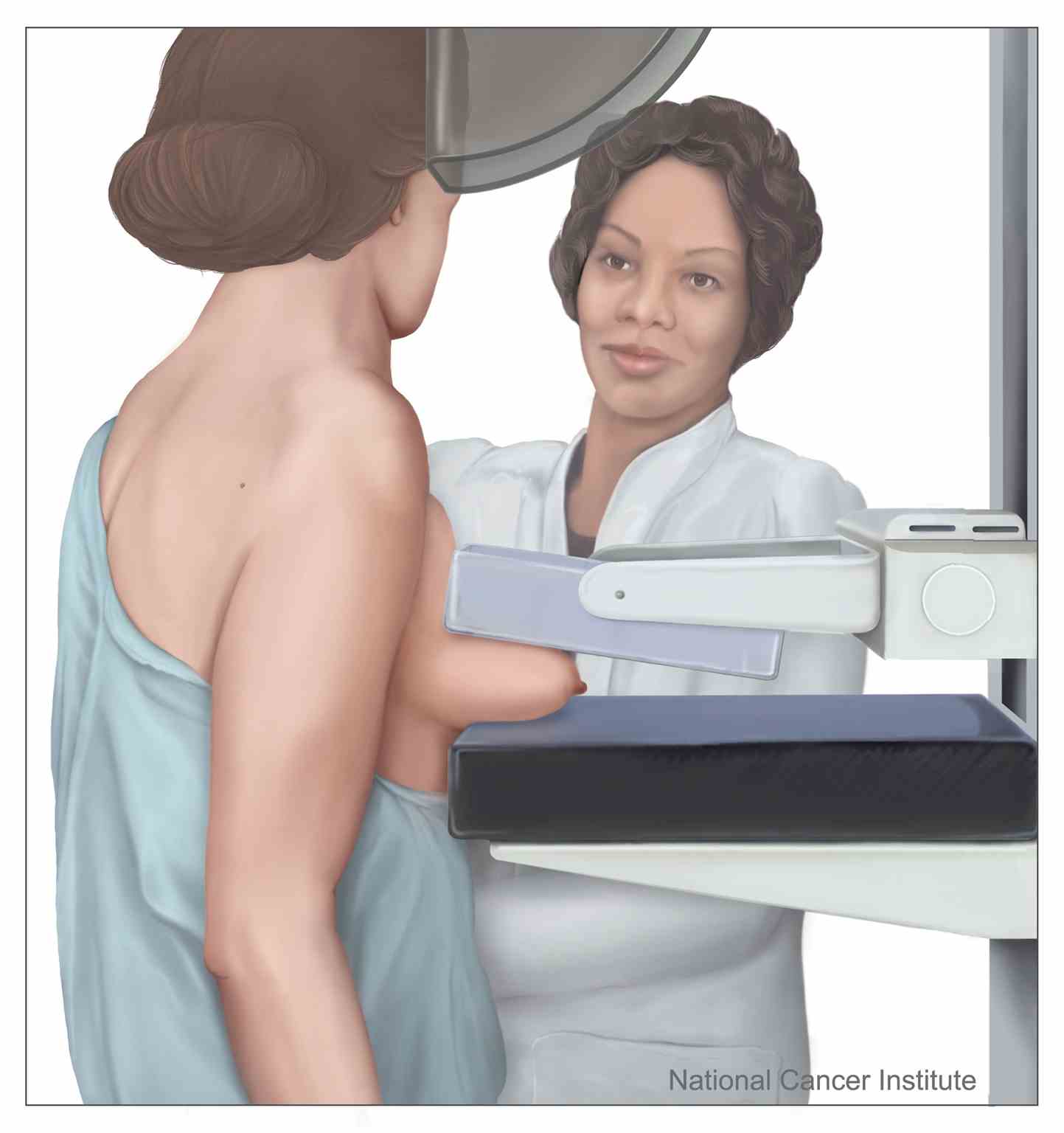

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jatoi I, Anderson WF, Rao SR, Devesa SS. Breast cancer trends among black and white women in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Nov 1:23(31):7836-41 [PubMed PMID: 16258086]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRojas K, Stuckey A. Breast Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Dec:59(4):651-672 [PubMed PMID: 27681694]

Hellquist BN, Duffy SW, Abdsaleh S, Björneld L, Bordás P, Tabár L, Viták B, Zackrisson S, Nyström L, Jonsson H. Effectiveness of population-based service screening with mammography for women ages 40 to 49 years: evaluation of the Swedish Mammography Screening in Young Women (SCRY) cohort. Cancer. 2011 Feb 15:117(4):714-22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25650. Epub 2010 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 20882563]

Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Moy L, Monsees B, Kopans DB, Eby PR, Sickles EA. Breast Cancer Screening for Average-Risk Women: Recommendations From the ACR Commission on Breast Imaging. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2017 Sep:14(9):1137-1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.06.001. Epub 2017 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 28648873]

Lee CI, Chen LE, Elmore JG. Risk-based Breast Cancer Screening: Implications of Breast Density. The Medical clinics of North America. 2017 Jul:101(4):725-741. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.03.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28577623]

Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, Calhoun KE, Daly MB, Farrar WB, Garber JE, Gray R, Greenberg CC, Greenup R, Hansen NM, Harris RE, Heerdt AS, Helsten T, Hodgkiss L, Hoyt TL, Huff JG, Jacobs L, Lehman CD, Monsees B, Niell BL, Parker CC, Pearlman M, Philpotts L, Shepardson LB, Smith ML, Stein M, Tumyan L, Williams C, Bergman MA, Kumar R. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2018 Nov:16(11):1362-1389. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0083. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30442736]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih YC, Walter LC, Church TR, Flowers CR, LaMonte SJ, Wolf AM, DeSantis C, Lortet-Tieulent J, Andrews K, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, Smith RA, Brawley OW, Wender R, American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015 Oct 20:314(15):1599-614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12783. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26501536]

. Practice Bulletin Number 179: Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average-Risk Women. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Jul:130(1):e1-e16. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002158. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28644335]

Karimi P, Shahrokni A, Moradi S. Evidence for U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations against routine mammography for females between 40-49 years of age. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2013:14(3):2137-9 [PubMed PMID: 23679332]

Expert Panel on Breast Imaging:, Mainiero MB, Moy L, Baron P, Didwania AD, diFlorio RM, Green ED, Heller SL, Holbrook AI, Lee SJ, Lewin AA, Lourenco AP, Nance KJ, Niell BL, Slanetz PJ, Stuckey AR, Vincoff NS, Weinstein SP, Yepes MM, Newell MS. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Breast Cancer Screening. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2017 Nov:14(11S):S383-S390. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.08.044. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29101979]

Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, Mendelson EB, Lehrer D, Böhm-Vélez M, Pisano ED, Jong RA, Evans WP, Morton MJ, Mahoney MC, Larsen LH, Barr RG, Farria DM, Marques HS, Boparai K, ACRIN 6666 Investigators. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2008 May 14:299(18):2151-63. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2151. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18477782]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, Jong RA, Pisano ED, Barr RG, Böhm-Vélez M, Mahoney MC, Evans WP 3rd, Larsen LH, Morton MJ, Mendelson EB, Farria DM, Cormack JB, Marques HS, Adams A, Yeh NM, Gabrielli G, ACRIN 6666 Investigators. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012 Apr 4:307(13):1394-404. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.388. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22474203]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNelson HD, Pappas M, Cantor A, Griffin J, Daeges M, Humphrey L. Harms of Breast Cancer Screening: Systematic Review to Update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Annals of internal medicine. 2016 Feb 16:164(4):256-67. doi: 10.7326/M15-0970. Epub 2016 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 26756737]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarant-Micallef C, Shield KD, Vignat J, Cléro E, Kesminiene A, Hill C, Rogel A, Vacquier B, Bray F, Laurier D, Soerjomataram I. The risk of cancer attributable to diagnostic medical radiation: Estimation for France in 2015. International journal of cancer. 2019 Jun 15:144(12):2954-2963. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32048. Epub 2019 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 30537057]

Rimawi BH, Green V, Lindsay M. Fetal Implications of Diagnostic Radiation Exposure During Pregnancy: Evidence-based Recommendations. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Jun:59(2):412-8. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000187. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26982251]

Expert Panel on Breast Imaging:, diFlorio-Alexander RM, Slanetz PJ, Moy L, Baron P, Didwania AD, Heller SL, Holbrook AI, Lewin AA, Lourenco AP, Mehta TS, Niell BL, Stuckey AR, Tuscano DS, Vincoff NS, Weinstein SP, Newell MS. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Breast Imaging of Pregnant and Lactating Women. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2018 Nov:15(11S):S263-S275. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30392595]

Sabate JM, Clotet M, Torrubia S, Gomez A, Guerrero R, de las Heras P, Lerma E. Radiologic evaluation of breast disorders related to pregnancy and lactation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2007 Oct:27 Suppl 1():S101-24. doi: 10.1148/rg.27si075505. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18180221]

Lewin JM, D'Orsi CJ, Hendrick RE. Digital mammography. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2004 Sep:42(5):871-84, vi [PubMed PMID: 15337422]

Sechopoulos I. A review of breast tomosynthesis. Part I. The image acquisition process. Medical physics. 2013 Jan:40(1):014301. doi: 10.1118/1.4770279. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23298126]

Chong A, Weinstein SP, McDonald ES, Conant EF. Digital Breast Tomosynthesis: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Radiology. 2019 Jul:292(1):1-14. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019180760. Epub 2019 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 31084476]

Gennaro G, Avramova-Cholakova S, Azzalini A, Luisa Chapel M, Chevalier M, Ciraj O, de Las Heras H, Gershan V, Hemdal B, Keavey E, Lanconelli N, Menhart S, João Fartaria M, Pascoal A, Pedersen K, Rivetti S, Rossetti V, Semturs F, Sharp P, Torresin A. Quality Controls in Digital Mammography protocol of the EFOMP Mammo Working group. Physica medica : PM : an international journal devoted to the applications of physics to medicine and biology : official journal of the Italian Association of Biomedical Physics (AIFB). 2018 Apr:48():55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2018.03.016. Epub 2018 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 29728229]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMora P, Faulkner K, Mahmoud AM, Gershan V, Kausik A, Zdesar U, Brandan ME, Kurt S, Davidović J, Salama DH, Aribal E, Odio C, Chaturvedi AK, Sabih Z, Vujnović S, Paez D, Delis H. Improvement of early detection of breast cancer through collaborative multi-country efforts: Medical physics component. Physica medica : PM : an international journal devoted to the applications of physics to medicine and biology : official journal of the Italian Association of Biomedical Physics (AIFB). 2018 Apr:48():127-134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2017.12.021. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29599081]

Loesch J. Regulatory Compliance in Mammography. Radiologic technology. 2016 Mar-Apr:87(4):425M-442M; quiz 443M-444M [PubMed PMID: 26952076]

Poplack SP, Tosteson AN, Grove MR, Wells WA, Carney PA. Mammography in 53,803 women from the New Hampshire mammography network. Radiology. 2000 Dec:217(3):832-40 [PubMed PMID: 11110951]

Duggan C, Dvaladze A, Rositch AF, Ginsburg O, Yip CH, Horton S, Camacho Rodriguez R, Eniu A, Mutebi M, Bourque JM, Masood S, Unger-Saldaña K, Cabanes A, Carlson RW, Gralow JR, Anderson BO. The Breast Health Global Initiative 2018 Global Summit on Improving Breast Healthcare Through Resource-Stratified Phased Implementation: Methods and overview. Cancer. 2020 May 15:126 Suppl 10(Suppl 10):2339-2352. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32891. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32348573]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence