Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly seen cancer diagnosis in women worldwide. Lymph node involvement is one of the most important prognostic factors in breast cancer and is important in determining the management of a breast cancer diagnosis. Lymphatic channels collect under the areola to form Sappey’s plexus. The axillary lymph nodes that drain the breast tissue about 75% of the time have been divided into three levels depending on their relationship with the pectoralis major muscle. Level one lymph nodes are lateral to the pectoralis major, level two lymph nodes are posterior to the pectoralis major, and level three lymph nodes are medial to the pectoralis major. Of note, the lymph node between the pectoralis major and minor muscles is also referred to as Rotter’s node. The internal mammary lymph node located beneath the sternum will be the predominant draining node about 5% of the time. In the other 25% of the time, drainage occurs into a combination of the axillary and internal mammary lymph nodes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The lymphatic channels become involved with breast cancer when the cancer cells become invasive, disrupting the basement membrane with potential metastatic spread. Although ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) implies that the cancer cells have not yet disrupted the basement membrane, about 10% to 20% of patients with DCIS will have a focus of invasive cancer seen in the pathologic specimen from their definitive surgery[1].

When there is obstruction of the dermal lymphatic channels by emboli of carcinoma cells, there is edema of the skin known as peau d’orange. This is a characteristic finding of inflammatory breast carcinoma.

Epidemiology

Over 180,000 women are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer annually in the United States, and over 40000 die secondary to breast cancer annually. Breast cancer in men accounts for less than 1% of all breast cancer diagnoses. The risk of developing breast cancer continues to increase over a woman's lifetime. A 30-year-old woman has a 1 in 257 chance of developing breast cancer, whereas a 60-year-old woman has a 1 in 24 chance. The probability of lymph node metastasis increases with the size of the tumor, lymphovascular invasion, and more aggressive biology. Axillary nodal metastasis is present in less than 1% of DCIS.[2]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of breast cancer is dependent on staging. Anatomic staging is based on the size of the tumor and lymph node status. The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging manual has added prognostic staging to breast cancer, which combines size, lymph node involvement, the grade of the tumor, and receptor status.[3][4]

Histopathology

Histological grade and specific tumor markers visible on pathology can also help distinguish how aggressive breast cancer may be. In axillary nodal disease, the poorer prognosis correlates with an increased number of nodes involved with tumor, extracapsular extension, and level III nodal disease.

History and Physical

Physical examination of the breast lymphatics occurs during the breast exam. The examiner can best palpate the axillary nodes with the patient sitting up and the examiner supporting the arms to the side, or the hands resting on the hips. The examiner should palpate the supraclavicular and infraclavicular lymph nodes as well.

Evaluation

A lymph node that is suspicious during the exam or mammography can undergo further evaluation with ultrasound. Suspicious findings on ultrasound include enlarged nodes, thickened cortex, and loss of fatty hilum. Any suspicious node on ultrasound should have a biopsy via core-needle biopsy or fine-needle aspiration (FNA). A clip is placed when performing a core-needle biopsy is done so that if the node is positive, it can be targeted for removal at surgery. FNA is 90% sensitive and 100% specific in the assessment of suspicious lymph nodes[3]. When performing diagnostic MRI, enhancing lymph nodes may be identified, warranting an ultrasound evaluation, and possible core-needle biopsy. Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy provides information on specific nodal basins and the location of lymph nodes. Sentinel node biopsy is an option in clinically node-negative patients.

Treatment / Management

A sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is indicated in staging the axilla in clinically node-negative breast cancer patients. This procedure is performed simultaneously with either a partial mastectomy or a simple mastectomy. Before incision, the subcutaneous tissue beneath the areola is injected with a radioactive tracer, blue dye, or both.[5] During the operation, the surgeon removes all "hot" and/or blue nodes. Any palpable, suspicious nodes are removed as well. The average number of removed sentinel nodes is between 1 and 4, with a median of 2 in most studies. The "10% rule" is followed when using the radioactive tracer by removing any node that has counts within 10% of the hottest node.(B2)

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is not routinely required when meeting the following criteria: partial mastectomy, T1-T2 tumor, one to two positive SLNs without extracapsular extension, planned whole breast irradiation, or adjuvant therapy is anticipated via hormonal therapy or cytotoxic therapy. This approach is based on the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial results, a trial that has changed the way a positive sentinel node is managed in patients undergoing breast conservation. ACOSOG Z0011 results are not applicable when patients have T3 or T4 tumors, are proceeding with a mastectomy, have more than two positive nodes, are undergoing partial breast radiation, had preoperatively matted, or palpable nodes, or have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy.[6] This trial revealed equivalent results in loco-regional failure and survival between patients undergoing ALND versus no further axillary surgery in patients with positive SLN via hematoxylin and eosin. (A1)

Two other trials, ACOSOG Z0010 and the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-32, have indicated that micrometastases in axillary lymph nodes detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) are clinically insignificant concerning survival.[7] The 5-year survival in patients with early breast cancer undergoing a partial mastectomy is not significantly affected by the presence of occult metastasis to the sentinel lymph nodes.[8] There has also been no difference shown between overall survival and locoregional recurrence. Thus, the IHC presence of disease does not change clinical management.(A1)

The incidence of axillary nodal disease in the setting of DCIS varies from 1.4% to 13%.[1] SLN biopsy should not be a routine consideration for breast conservation in DCIS but should be considered when performing a mastectomy due to the possibility of finding invasive malignancy in the specimen.(B2)

The likelihood of additional nodes being involved with cancer when a sentinel node contains metastatic disease is directly proportional to the tumor size, size of lymph node metastatic lesion, the presence of lymphovascular invasion, hormonal and HER2 receptor status, grade, and the age at diagnosis.[3] About half of the time, the sentinel lymph node is the only positive node.

ALND should be done routinely for locally advanced cancer, inflammatory cancer, presence of a positive sentinel lymph node in a patient having a mastectomy, a positive sentinel lymph node in a patient who is undergoing accelerated partial breast radiation, or a positive sentinel lymph node in a patient who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In patients who have more than three positive axillary nodes, axillary radiation will be an added therapy. If patients have clinically suspicious internal mammary nodes on imaging, radiation to the internal mammary nodes should be offered as well. It is crucial to consult radiation and medical oncology to coordinate care in these complex patients.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of axillary or supraclavicular adenopathy includes reactive nodes from an infectious process or malignancy unrelated to breast cancer, including lymphoma, head and neck tumors, melanoma, or lung cancer.

Surgical Oncology

Early trials in breast cancer research confirmed the validity and safety of sentinel node biopsy. The adoption of this technique helped avoid axillary dissection for node-negative patients, decreasing the morbidities associated with this surgery[9].

Over time, the clinical relevance of a positive sentinel node continues to be studied.

The ACOSOG Z0011 trial has been practice-changing for sentinel node management in patients with clinically negative axilla. This study guides treating surgeons to avoid an ALND when performing breast conservation, and only 1 to 2 positive sentinel nodes are present and administering postoperative radiation. The results from this are not applicable in women with T3 or T4 tumors, those who have an extracapsular extension, or those who undergo partial breast radiation.

There are ongoing trials for patients who have a core-needle biopsy-proven axillary nodal metastasis who then undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy with complete imaging response of the axilla. One trial is Alliance A11202, in which patients who have node biopsy-proven disease before neoadjuvant chemotherapy will undergo SLN at the time of surgery. If the SLN is negative, there will be no further surgery. If the SLN is positive, these patients are randomized to chest wall/nodal radiation with or without further ALND. The NSABP B51-RTOG 1304 (NRG 9353) schema follows patients with the documented nodal disease to have either SLN or ALND at the time of surgery, and then randomization with or without nodal radiation [American Society of Breast Surgeons 2019 Annual meeting].[10]

Radiation Oncology

The clinician should pursue radiation in patients who have had a mastectomy and have N2 or N3 disease. It can be a consideration for patients who have lymphovascular invasion or a positive nodal ratio greater than 20%. There is data to support axillary radiation with postmastectomy radiation in patients with 1 to 2 positive nodes as an alternative to axillary dissection, and a discussion with a radiation oncologist is integral to making these decisions.[11][12][13] Ongoing trials are underway to define when axillary nodal dissection is avoidable.[10]

Medical Oncology

Adjuvant therapy recommendations are based on the prognostic stage of the disease. Cytotoxic chemotherapy can reduce mortality by about 25%. The primary agents used are anthracyclines such as doxorubicin and epirubicin, and taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel. Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors are used in patients with hormone receptor-positive disease to decrease locoregional recurrence, reduce contralateral disease, and improve survival. Trastuzumab and pertuzumab are agents administered in patients with positive HER2 receptors.

The indications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy are in continual flux. Historically only used in patients with inflammatory breast cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is now used in women with node-positive disease proven with core-needle biopsy, and T2 tumors that are either HER2 positive or triple-negative. Although there is no survival difference in neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy, there is an increase in the rate of breast conservation and a decrease in the extent of axillary surgery when patients with a metastatic node convert to node-negative. Additionally, the responsiveness of the tumor is assessed on pathology after surgery, which gives important prognostic information.

Staging

The recent AJCC 8th edition has redefined the staging of breast cancer. Anatomic staging using only the size of the tumor and the lymph node status has been replaced by prognostic staging, which incorporates tumor size, lymph node involvement, grade, and receptor status. Pathologic lymph node staging is N0 for no nodal involvement, N1 for 1 to 3 nodes involved, N2 for 4 to 9 nodes involved, and N3 for over 9 nodes involved. Metastasis to the ipsilateral axillary nodes is more predictive of outcome than tumor size. The presence of micrometastasis has been included in the staging process. Tumor deposits less than or equal to 0.2 mm classify as N0[i+], and deposits greater than 0.2 mm and less than or equal to 2.0 mm have are N1mi.[14]

Prognosis

Lymphatic invasion doubles the risk of local recurrence of invasive ductal carcinoma after breast-conserving surgery. Local recurrence usually is 0.5% to 1%. Internal mammary lymph node involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, with a ten-year survival rate between 37% to 62%.[15] Inflammatory breast cancer is the cause of 1% to 5% of breast cancers and is the most aggressive form. The disease progresses in weeks to a few months. With a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, relapse-free survival is about 50% at five years.

Complications

A common complication of breast cancer treatment is lymphedema. The impaired outflow of lymph causes fluid build-up in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper extremities. This condition is likely secondary to the destruction of upper limb lymphatic channels during surgery and/or radiation. At five years, 5% of patients who have had sentinel lymph node biopsy and 16% of patients who have had axillary lymph node dissection will develop lymphedema.[16] There are four stages of lymphedema. Stage 0 is subclinical, stage 1 is swelling that resolves with limb elevation, stage 2 is swelling that is persistent with associated fibrosis, and stage 3 is fibrosis with fatty deposits and warts (aka elephantiasis). A comparison of limb circumference is the accepted mode of evaluating for lymphedema, but newer techniques, including bioimpedance, are used as well.[17] Consultation with a lymphedema specialist is advisable to provide prevention and management strategies.

Surgical interventions such as lymph node transfer or lymphaticovenular anastomosis are last-resort procedures if conservative strategies fail, and patients experience recurrent lymphangitis, intractable pain, or impairment of limb function. These are offered only in specialized centers.

Nerve injury can also occur during axillary surgery. This damage includes the long thoracic nerve (which results in scapular winging), thoracodorsal nerve, and intercostobrachial nerve. One needs to be careful to avoid injuring these nerves, including avoiding paralytic agents during anesthesia and proper identification of anatomy.[18]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients who undergo lymphatic dissection or radiation benefit from visiting lymphedema specialists who can provide them with the appropriate exercises, compression devices and garments, and education to prevent or manage lymphedema.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be able to express their concerns about breast cancer and management openly with health care professionals. There may be cultural, social, or economic barriers that prevent individuals from seeking breast examination and screening. Lymphedema should be part of the discussion in the informed consent process before any breast or axillary procedure, and patients should receive education covering the prevention and management of lymphedema.

Pearls and Other Issues

Preoperative assessment of the axilla in breast cancer with ultrasound and core needle biopsy or FNA for nodes with thickened cortex or loss of fatty hilum might alter treatment pathways and management. Biopsy-proved axillary disease should prompt evaluation for neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and the management of the axilla during surgery will depend on the responsiveness of the tumor after chemotherapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Breast cancer is an interprofessional disease. It is crucial to evaluate the patient in detail with a mammogram, ultrasound, and possibly MRI imaging, core biopsies, and an interprofessional consideration before a therapeutic plan begins. Breast cancer conferences are essential to orchestrate between the specialties, especially in node-positive disease. Communication and management guidelines shared between the breast surgeon, radiologist, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, pathologist, geneticist, lymphedema specialist, and possibly plastic surgeon are essential in ensuring patients receive optimal individualized care. Pharmacists with oncology board certification should consult on all chemotherapy regimens; they will also check dosing, counsel on adverse effects, and check for drug interactions. Breast care nurses assist in coordinating care, while pharmacists are involved in reviewing medications. WIth interprofessional collaboration between members of the healthcare team, patients can achieve better outcomes with fewer adverse events. [Level 5]

Media

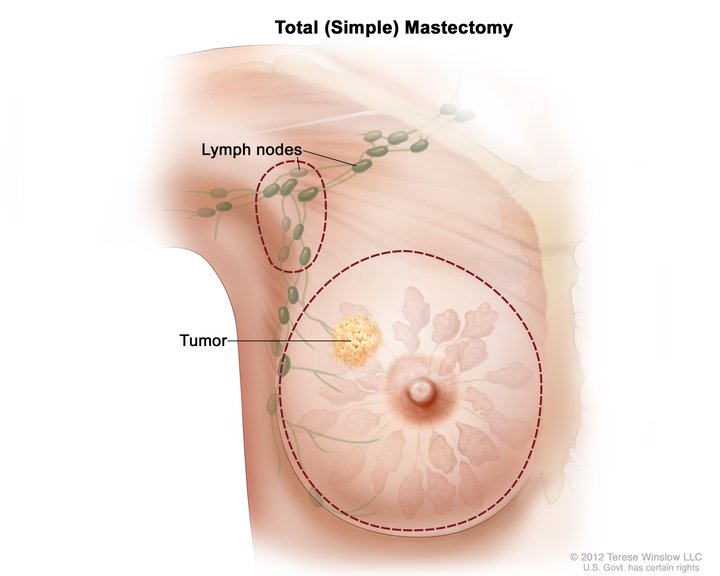

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Total Simple Mastectomy. This illustration shows a scheme for removing the breast and lymph nodes in a total (simple) mastectomy. The dotted line shows where the breast incision is made. The procedure may also include axillary lymph node dissection.

National Cancer Institute, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

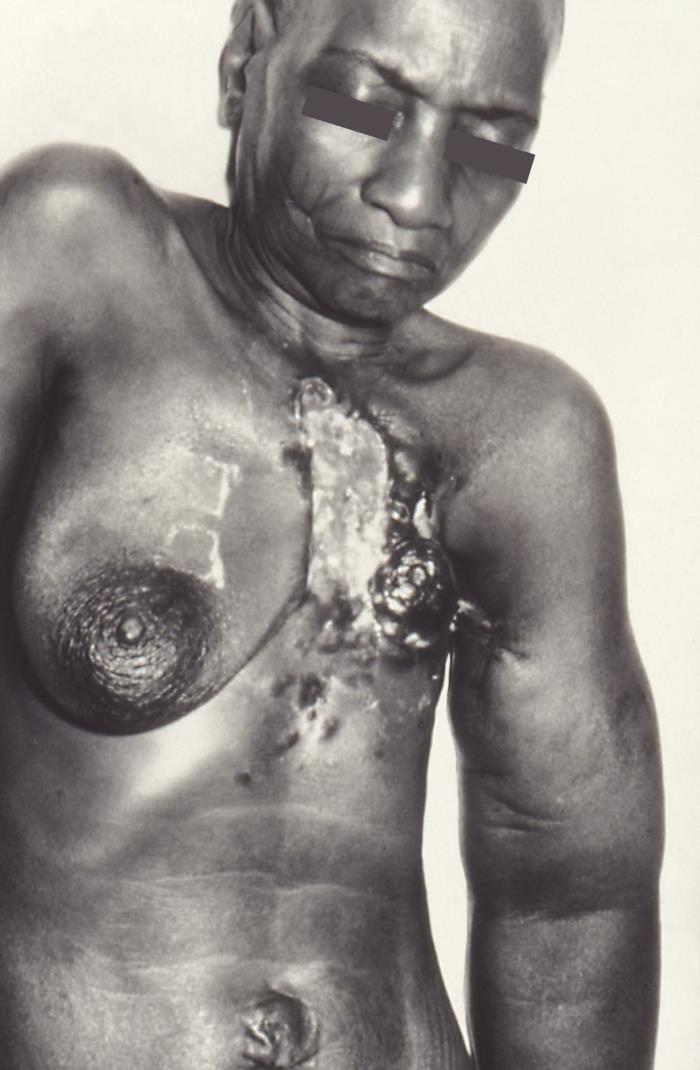

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bertozzi S, Cedolini C, Londero AP, Baita B, Giacomuzzi F, Capobianco D, Tortelli M, Uzzau A, Mariuzzi L, Risaliti A. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients affected by breast ductal carcinoma in situ with and without microinvasion: Retrospective observational study. Medicine. 2019 Jan:98(1):e13831. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013831. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30608397]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVirnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T, Kane RL. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment, and outcomes. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010 Feb 3:102(3):170-8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp482. Epub 2010 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 20071685]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHouvenaeghel G, Lambaudie E, Classe JM, Mazouni C, Giard S, Cohen M, Faure C, Charitansky H, Rouzier R, Daraï E, Hudry D, Azuar P, Villet R, Gimbergues P, Tunon de Lara C, Martino M, Fraisse J, Dravet F, Chauvet MP, Boher JM. Lymph node positivity in different early breast carcinoma phenotypes: a predictive model. BMC cancer. 2019 Jan 10:19(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5227-3. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30630443]

Yoon EC, Schwartz C, Brogi E, Ventura K, Wen H, Darvishian F. Impact of biomarkers and genetic profiling on breast cancer prognostication: A comparative analysis of the 8th edition of breast cancer staging system. The breast journal. 2019 Sep:25(5):829-837. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13352. Epub 2019 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 31197914]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYuan L, Qi X, Zhang Y, Yang X, Zhang F, Fan L, Chen L, Zhang K, Zhong L, Li Y, Gan S, Fu W, Jiang J. Comparison of sentinel lymph node detection performances using blue dye in conjunction with indocyanine green or radioisotope in breast cancer patients: a prospective single-center randomized study. Cancer biology & medicine. 2018 Nov:15(4):452-460. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0270. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30766755]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGiuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, Beitsch PD, Brennan MB, Kelemen PR, Ollila DW, Hansen NM, Whitworth PW, Blumencranz PW, Leitch AM, Saha S, Hunt KK, Morrow M. Effect of Axillary Dissection vs No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017 Sep 12:318(10):918-926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28898379]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAmersi F, Giuliano AE. Management of the axilla. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2013 Aug:27(4):687-702, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.05.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23915739]

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Costantino JP, Ashikaga T, Weaver DL, Mamounas EP, Jalovec LM, Frazier TG, Noyes RD, Robidoux A, Scarth HM, Wolmark N. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2010 Oct:11(10):927-33. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20863759]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchwartz GF, Guiliano AE, Veronesi U, Consensus Conference Committee. Proceeding of the consensus conference of the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in carcinoma or the breast April 19-22, 2001, Philadelphia, PA, USA. The breast journal. 2002 May-Jun:8(3):124-38 [PubMed PMID: 12078657]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEverett AS, De Los Santos JF, Boggs DH. The Evolving Role of Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2018 Aug:98(4):801-817. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.03.010. Epub 2018 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 30005775]

Weiss A, Lin H, Babiera GV, Bedrosian I, Shaitelman SF, Shen Y, Kuerer HM, Mittendorf EA, Caudle AS, Hunt KK, Hwang RF. Evolution in practice patterns of axillary management following mastectomy in patients with 1-2 positive sentinel nodes. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2019 Jul:176(2):435-444. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05243-7. Epub 2019 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 31025270]

Yan M, Abdi MA, Falkson C. Axillary Management in Breast Cancer Patients: A Comprehensive Review of the Key Trials. Clinical breast cancer. 2018 Dec:18(6):e1251-e1259. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.08.002. Epub 2018 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 30262257]

Grossmith S, Nguyen A, Hu J, Plichta JK, Nakhlis F, Cutone L, Dominici L, Golshan M, Duggan M, Carter K, Rhei E, Barbie T, Calvillo K, Nimbkar S, Bellon J, Wong J, Punglia R, Barry W, King TA. Multidisciplinary Management of the Axilla in Patients with cT1-T2 N0 Breast Cancer Undergoing Primary Mastectomy: Results from a Prospective Single-Institution Series. Annals of surgical oncology. 2018 Nov:25(12):3527-3534. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6525-3. Epub 2018 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 29868979]

Dutta SW, Volaric A, Morgan JT, Chinn Z, Atkins KA, Janowski EM. Pathologic Evaluation and Prognostic Implications of Nodal Micrometastases in Breast Cancer. Seminars in radiation oncology. 2019 Apr:29(2):102-110. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2018.11.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30827448]

Kim J, Chang JS, Choi SH, Kim YB, Keum KC, Suh CO, Yang G, Cho Y, Kim JW, Lee IJ. Radiotherapy for initial clinically positive internal mammary nodes in breast cancer. Radiation oncology journal. 2019 Jun:37(2):91-100. doi: 10.3857/roj.2018.00451. Epub 2019 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 31266290]

Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Cowher MS, Taback B, McLaughlin S, Ajkay N, Boyages J, Koelmeyer L, DeSnyder SM, Wagner J, Abramson V, Moore A, Shah C. A Randomized Trial Evaluating Bioimpedance Spectroscopy Versus Tape Measurement for the Prevention of Lymphedema Following Treatment for Breast Cancer: Interim Analysis. Annals of surgical oncology. 2019 Oct:26(10):3250-3259. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07344-5. Epub 2019 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 31054038]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLim SM, Han Y, Kim SI, Park HS. Utilization of bioelectrical impedance analysis for detection of lymphedema in breast Cancer survivors: a prospective cross sectional study. BMC cancer. 2019 Jul 8:19(1):669. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5840-9. Epub 2019 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 31286884]

Nevola Teixeira LF, Lohsiriwat V, Schorr MC, Luini A, Galimberti V, Rietjens M, Garusi C, Gandini S, Sarian LO, Sandrin F, Simoncini MC, Veronesi P. Incidence, predictive factors, and prognosis for winged scapula in breast cancer patients after axillary dissection. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014 Jun:22(6):1611-7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2125-3. Epub 2014 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 24492929]