Introduction

Hearing loss is relatively common in newborns and children, with an estimated prevalence of 1.1-3.5 per 1,000 newborns screened.[1][2][3] Up to 20% of children are affected by some degree of hearing loss by age 18, underscoring the need for appropriate diagnostic and intervention techniques to prevent negative sequelae of hearing loss. Undiagnosed and untreated, hearing loss can have significant consequences, including speech and language developmental delays, vestibular dysfunction, increased anxiety and depression, and decreased well-being and self-esteem.[4][5][6]

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health published recommendations that all newborns obtain routine hearing screening by 3 months of age. The Joint Committee on Infant Hearing published its first position statement in 1994, with updates made in 2000, 2007, and most recently in 2019. The 2007 guidelines called for newborn hearing screening to be performed in all newborns by 1 month of age, with definitive diagnostic audiometric testing completed by 3 months for those who did not pass, and finally, with the initiation of an appropriate intervention by 6 months of age.[7] These recommendations have been adopted widely in the United States, with recent data indicating that 98% of all newborns completed initial screening for hearing loss within 1 month of birth. This led to the updated recommendation 2019 that screening, diagnostic testing, and intervention be completed in 1 month, 2 months, and 3 months, respectively, wherever possible.

Hearing loss may be unilateral or bilateral. Unilateral hearing loss is frequently considered less problematic than bilateral hearing loss, although more recent data has demonstrated its clinical significance. Balanced input to both ears is essential for developing binaural hearing pathways early in life.[8] Without binaural hearing, sound localization is more difficult and can significantly affect patients, especially when trying to hear in the presence of background noise through decrements in binaural squelch.[9] Children with unilateral hearing loss have a 10-fold higher risk of repeating at least 1 grade in school than normal-hearing children (35% vs. 3.5% respectively). Up to 40% require additional educational assistance.[10] Unilateral hearing loss has also been reported to progress into bilateral hearing loss in 7.5 to 11% of cases, demonstrating the importance of active diagnosis and treatment of unilateral and bilateral hearing loss. Cochlear malformations such as Mondini dysplasia or enlarged vestibular aqueduct have been reported to be responsible for greater than 50% of unilateral hearing loss in children.[11]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The experience of hearing requires structural and neural processes to work in coordination to transmit a mechanical sound wave into an electrical stimulus that the brain can interpret. Due to the differences in the surface area of the tympanic membrane and the stapes, and through the processes of ossicular coupling and acoustic coupling, sound pressure through the middle ear space is amplified such that the mechanical transmission of sound at the stapes is 82.5 times greater than at the tympanic membrane.[12] The inner ear portion responsible for hearing is the cochlea, divided into the scala vestibuli superiorly, the scala tympani inferiorly, and the scala media between the 2. The scala vestibuli and scala media are separated by the Reissner membrane, and the scala media is separated from the scala tympani by the basilar membrane. The scala vestibuli and scala tympani contain perilymph, which closely resembles extracellular fluid, while the scala media contains endolymph, which resembles intracellular fluid. Within the scala media is the organ of Corti, which contains inner and outer hair cells and the tectorial membrane.

Transmission of mechanical energy into the middle ear via movement of the stapes footplate causes fluid pressure shifts, which causes the tectorial membrane to contact and depolarize tonotopically arranged hair cells. Low-frequency sounds preferentially stimulate the apex of the cochlea, while high-frequency sounds stimulate the base. The hair cells then generate an electrochemical signal that is transmitted to the brain with the pathway progressing to the auditory nerve, cochlear nucleus, lateral lemniscus, inferior colliculus, superior olivary complex, medial geniculate body, and terminating at the primary auditory cortex on the superior surface of the temporal lobe.

The 2 primary testing methods used in the newborn hearing screening are otoacoustic emissions (OAE) and automated auditory brainstem response (AABR). Otoacoustic emissions result from detecting cochlear outer hair cells moving in response to a sound stimulus from the environment, which is recorded by a probe placed in the patient’s ear. While multiple types of OAEs exist, transient evoked OAE (TEOAE) and distortion product OAE (DPOAE) are the most common tests used in newborn screening. TEOAE can generally be detected by 30 weeks gestation and involves using a broadband signal to assess cochlear function. At the same time, DPOAE is generally more frequency-specific but does not perform as well as TEOAE below 4 kHz.

The presence of an OAE is commonly used to reflect an entire auditory system and is designated as a pass in newborn hearing screening. In contrast, the absence of an OAE is designated as a referral needed[13]. An absent OAE generally corresponds to either middle ear pathology or a sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) of at least 40 decibels (dB). The presence of OAEs does not rule out hearing loss, as the OAE tests the mechanical function of the cochlea.

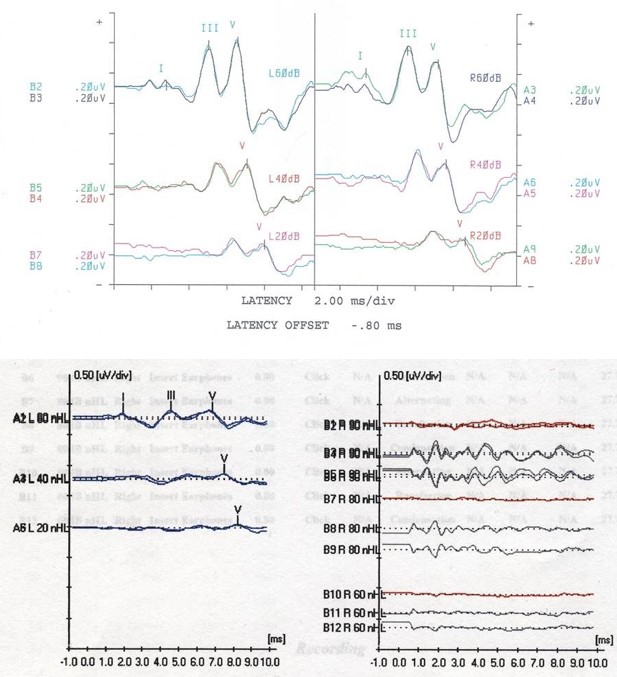

AABR is used to test the electrical function of the auditory pathway. This test utilizes electrodes placed on the scalp to detect electrical activity along the transmission pathway, with results seen through 5 waves that indicate a different portion of the auditory pathway. Wave I corresponds to the auditory nerve (cranial nerve VIII), wave II to the cochlear nucleus, wave III to the superior olivary complex, wave IV to the lateral lemniscus, and wave V to the inferior colliculus. The decreased amplitude or increased latency in a specific wave can indicate the severity of hearing loss and the location of an abnormality when 1 is present. Up to 10% of patients with a dyssynchronous ABR or an ABR indicating severe to profound hearing loss have been diagnosed with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD). See Image. Auditory Brainstem Response Test.

In ANSD, the sound is appropriately transmitted to the inner ear, and a neural signal is generated, but there is abnormal conduction of the neural signal to the brain. Hence, diagnostic criteria for ANSD include normal OAEs but absent or severely abnormal ABR with maximal stimulus.[14] While ANSD can be unilateral, it is bilateral in most cases.[15] Acoustic reflexes are absent bilaterally in most cases of ANSD, although this is not a universal finding and is not part of the diagnostic criteria.f

Indications

All newborns should be screened for hearing loss before being discharged from the hospital. Those who pass the initial screening should follow up in their primary care medical home. Those who do not pass should be re-tested before discharge, with repeat testing occurring at least several hours after the initial screening.[7] In the well-baby nursery, this testing is often performed using OAEs. Newborns with risk factors for hearing loss should receive screening with AABR testing due to the higher risk of ANSD in these patients. Significant risk factors for hearing loss in children include care in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for 5 days or longer, hyperbilirubinemia requiring exchange transfusion, culture-proven sepsis, and administration of ototoxic medications.[3] Newborns cared for in the NICU have been shown to have a 6.9 times higher risk of hearing loss than newborns who do not require NICU care. Additional risk factors include in-utero infection, neonatal infection, and craniofacial abnormalities or syndromic conditions.[11] The risk of ANSD in healthy newborns is low enough that ABR is not a requirement for those who pass initial OAE screening.

In addition to newborn testing, children should be referred for further audiologic testing when a parent/caregiver, teacher, or other medical professional has concerns regarding the hearing. Research has demonstrated that parents often underestimate hearing loss in their children, though a 61% detection rate has been reported for parents or guardians who suspect hearing loss.[16] Detection rates when speech pathologists or school teachers suspected hearing loss are reported as 36% and 18%, respectively.

Contraindications

There are no contraindications to hearing screening in newborns and children. Patients with congenital aural atresia or other visible ear deformities may not need to undergo screening while in the newborn nursery, as it would be expected to be abnormal, but should always have a referral placed immediately for comprehensive audiology evaluation to guide the next steps.[7]

Equipment

Standard audiometry equipment should be available for OAE, ABR, tympanometry, and comprehensive age-appropriate audiometric equipment. Examples of age-appropriate testing are described below in further detail. Visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA) is most appropriate for children under age 2 who can sit upright unassisted and demonstrate good head and neck control to turn the head toward a sound stimulus. This most often occurs at approximately 6 months of corrected age. From age 2 until age 5, or until the child can more meaningfully participate in an evaluation, conditioned play audiometry (CPA) is the recommended evaluation approach. Standard pure-tone audiometry (PTA) is utilized after age 5 or sooner if the child can participate. Acoustic reflex testing is often employed in evaluating adults and older children, although it is not frequently used to evaluate newborns and young children.

Personnel

The assessment and care of children with hearing loss are best accomplished through a multi-disciplinary team. They should include an audiologist skilled in the audiometric techniques used in children, an otolaryngologist, and a pediatrician. A geneticist should be consulted in cases where ANSD or a hereditary etiology is suspected, as 50% of cases of ANSD have been shown to have a genetic component.[14] Additionally, patients with known genetic abnormalities such as sickle cell disease should undergo comprehensive audiometric testing, as these patients are known to have an elevated risk of hearing loss.[17] Patients who present with non-syndromic SNHL have a 2 to 3 times higher risk of having ocular abnormalities, and hence, ophthalmology should also be consulted in these patients.[18]

Preparation

Children must be able to participate in the planned testing method, or the results may not be valid. Cooperation can be optimized by ensuring that older children are well-fed and well-rested and that hygiene, such as diaper changes, are performed just before testing where applicable. Newborns should not be fed or rested before arriving for evaluation, especially for a non-sedated ABR; at the time of assessment, monitors should be connected to the patient, after which point the patient should be fed and allowed to sleep during the examination. This maximizes the chance of appropriate behavior and accurate results from testing.

Technique or Treatment

Several techniques are available to screen for hearing loss. Newborn screening is typically via OAE or ABR, with further diagnostic testing including tympanometry, behavioral, and pure-tone audiometry as needed. The role of imaging and genetic testing in evaluating pediatric hearing loss is briefly discussed below.

Otoacoustic Emissions

A probe is placed within the child's ear and serves as a stimulus emitter and recorder. Standard testing utilizes multiple frequencies ranging from 2000 Hz to 5000 Hz. Many practices use TEOAE for screening purposes, although both TEOAE and DPOAE are acceptable. Results are binary and qualitative with either a "pass" or "refer" result based on cochlear microphonics' presence or absence.

Auditory Brainstem Response

Earphones are placed in the child's ear, and electrodes are placed on the scalp. If the patient is a newborn or young child, feeding and performing diaper hygiene may facilitate sleep. The earphones emit a sound signal ranging in frequency and intensity that is detectable by electrical changes on a monitor. The results can be viewed at waves I to V, representing the anatomic landmarks described in the Anatomy & Physiology section.

Tympanometry

An ear probe with a soft tip (immittance probe) is placed within the ear canal of the test ear, with the tip sealing the ear to maintain pressure. The pressure within the external ear changes while the child hears low-frequency noise stimuli. Recordings of the movement of the tympanic membrane are obtained. The standard probe tone is a 226 Hz signal, used for most purposes in children over 6 months of age. Some research suggests that a 1000 Hz probe tone may be more accurate at diagnosing middle ear effusions in children under 6 months old due to improved stiffening of the tympanic membrane with a higher frequency probe tone.

A typical tympanogram indicates the ear canal volume in cubic centimeters, the maximum pressure in decapascals (daPa), and the peak compliance in milliliters (ml). "Type A" tympanograms suggest normal middle ear function with peak compliance between -100 and +100 daPa and compliance from 0.3 to 1.5ml. "Type Ad" and "Type As" tympanograms demonstrate highly compliant and less compliant middle ear systems, respectively. "Type B" or flat tympanograms occur when there is no identifiable peak compliance, usually due to the presence of middle ear fluid or a perforated eardrum. An ear canal volume (ECV) larger than 1.5 cm suggests a perforation or the presence of a tympanostomy tube in the tympanic membrane. "Type C" tympanograms demonstrate peak compliance below -100 daPa and suggest negative middle ear pressure and eustachian tube dysfunction.

Acoustic Reflex Testing

While not commonly performed in newborns or children, reflex testing may be employed in certain circumstances. An immittance probe is inserted into the test ear, and a second probe is placed in the other ear. A 1000 Hz tone is typically used in neonates, while a 226 Hz tone is more commonly used after the neonatal period. A sound stimulus is initiated at 70-80 dB sound pressure level (SPL) with 5 dB SPL increases until an acoustic reflex is detected due to stapedial contraction. Stimulus intensity should not exceed 105 dB SPL unless conductive hearing loss is suspected. Results can be confirmed by repeating the test or increasing the intensity by 5 dB SPL and ensuring a reflex is present. Reflex testing is not performed if a patient is found to have a flat or type B tympanogram.

Behavioral Audiometry

Between approximately 6 to 24 months of age, children should undergo VRA testing. A patient must be able to sit unassisted and have enough head and neck control to turn the entire head toward a sound stimulus. Earphones are placed in the child's ear, and visual reinforcers are placed at 90 degrees to the patient's left and right sides. Examples of visual reinforcers may include a toy behind tinted glass or a video-based reinforcer. Sound stimuli are presented to both ears at different frequencies and intensities. When the child correctly turns to the direction of the ear in which the sound was presented (turning right when stimulus is presented to the right ear), they are rewarded with either a video clip or a view of the toy. From ages 2-5 years, children undergo audiometric testing via CPA. Sound stimuli are presented to both ears via headphones or earphones with varying frequencies and intensities. The child participates via play, such as putting a peg into a board or placing a ball into a basket in response to a sound. Testing can occur at different frequencies until all frequencies have been tested in both ears.

Pure-Tone Audiometry

Pure tone audiometry is often considered the standard form of audiometry. It can generally be performed on patients older than age 5, although some patients may be able to participate earlier than 5, and some may be slightly delayed. Headphones are placed on the patient's head, and sounds of varying frequencies and intensities are presented to each ear. The patient is typically given a button to depress each sound heard. An alternative setup for children may include a verbal response, raising the hand, or clapping whenever a sound stimulus is heard. This continues until all frequencies have been tested bilaterally, and threshold levels can be calculated based on the procedure results.

Imaging

Both CT and MRI may be used to evaluate pediatric hearing loss. However, research and consensus expert opinion favors not ordering routine imaging for children with bilateral hearing loss.[14] Imaging may benefit children with ANSD or unilateral hearing loss; however, the diagnostic yield of relevant findings in imaging for unilateral hearing loss is reported as only 37% for CT and 35% for MRI.[19] Children who may be considered candidates for cochlear implants should undergo an MRI to rule out cochlear dysplasia or cochlear nerve aplasia, which are contraindications to implantation.

Genetic and Laboratory Testing

Patients with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss or ANSD may benefit from a genetic workup. Approximately 50% of congenital hearing loss is reportedly genetic, with the vast majority of genetic cases being non-syndromic in nature. Syndromic cases can be divided into autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive cases. Common causes of autosomal dominant congenital hearing loss include Waardenburg syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, branchio-oto-renal syndrome, and neurofibromatosis. The most common causes of autosomal recessive congenital hearing loss include Usher, Pendred, and Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndromes. After audiometry, genetic testing has been shown to have the second-highest diagnostic rate of any single test for bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Asymmetric hearing loss is unlikely due to genetic causes and should not routinely prompt a genetics evaluation.

While 50% of congenital hearing loss is genetic, 50% is acquired. The most common cause of acquired hearing loss is congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, responsible for approximately 25% of all cases of congenital hearing loss. Within the first 3 weeks of life, CMV testing can be performed via saliva or urine samples; however, after 3 weeks, these samples become less accurate, and testing is performed using blot spot testing. Previous guidelines have suggested that no treatment for congenital CMV is necessary unless the patient is experiencing other symptoms of CMV infection. Limited research has shown a potential role for oral valganciclovir in improving hearing outcomes in patients with asymptomatic congenital CMV infection; however, this treatment has not been FDA-approved.[20]

Complications

While there are no significant complications from assessing for hearing loss in children, the primary concern is the risk of false results, both false positives and, more importantly, false negatives. A false positive or a falsely abnormal test may result in additional testing for the patient and added stress or anxiety for parents and caregivers, but ultimately, it will not result in long-term deficits for the patient. On the other hand, false negative or falsely normal testing in a patient with hearing loss may result in a delayed diagnosis of hearing loss.

The associated social, intellectual, and developmental consequences of false-negative assessments may negatively affect the child's developmental potential. Complications of the hearing assessment, such as perforation of the tympanic membrane or injury to the ear canal, are rare and typically not long-term. These risks are present whenever the ear is instrumented. The presence of behavioral concerns during evaluation may increase the risk of any of the above complications and make the testing more challenging to perform. Behavioral issues may decrease the accuracy of results.

Clinical Significance

As further research is conducted, significant harmful effects of hearing loss have been revealed. When diagnosed early, interventions can be put into place to optimize one’s chance for normal hearing and development. Primary interventions include conventional hearing aids, bone-anchored hearing aids (BAHA) with softband for children under age 5, contralateral routing of signals (CROS) hearing aids, and remote microphone systems. The patient should be evaluated for cochlear implantation when hearing loss is severe enough.[11] Hearing aids have been shown to reduce hearing thresholds by up to 25 dB hearing loss (HL); however, in severe to profound hearing loss, hearing aids perform much worse than cochlear implantation.[21] Cochlear implantation leads to hearing thresholds similar to control patients, with word reception scores of 85%.[22] Decreased developmental delays are also noted in patients with cochlear implantation, with 95% of implanted patients not requiring learning adaptations or full-time educational support.[23]

If screening is not performed or careful attention is not paid to following up on abnormal results, patients may not have hearing loss diagnosed until later when the brain is less plastic. The ability to integrate a hearing intervention is made more difficult. Data from the 2018 Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Hearing Screening and Follow-Up Survey indicate loss of follow-up in greater than 1 in 4 patients nationwide.[24] These patients are at much higher risk for social, developmental, and intellectual delays. While significant progress has been accomplished since the initiation of newborn hearing screening in 2001, continued efforts must be made to close the gap between diagnostic completion and initiation of therapy. Genetic testing and imaging may play a role in evaluating some patients with hearing loss; however, these should not be ordered routinely for every patient. With proper implementation of the 1-3-6 month guidelines at a minimum and 1-2-3 month guidelines where possible, children with hearing loss can usually develop and attain a high quality of life.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The assessment and management of hearing loss in children involve a multidisciplinary approach. Healthcare providers should work together as part of a coordinated team to ensure the rapid diagnosis and initiation of appropriate interventions. Communication between specialists is crucial to ensure that appropriate care is provided to each patient and that patients do not become lost to follow-up. Without a patient-centered team approach, efforts to improve the developmental potential of patients with hearing loss falter.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Butcher E, Dezateux C, Cortina-Borja M, Knowles RL. Prevalence of permanent childhood hearing loss detected at the universal newborn hearing screen: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2019:14(7):e0219600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219600. Epub 2019 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 31295316]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGustafson SJ, Corbin NE. Pediatric Hearing Loss Guidelines and Consensus Statements-Where Do We Stand? Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2021 Dec:54(6):1129-1142. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2021.07.003. Epub 2021 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 34535279]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFarinetti A, Raji A, Wu H, Wanna B, Vincent C. International consensus (ICON) on audiological assessment of hearing loss in children. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2018 Feb:135(1S):S41-S48. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2017.12.008. Epub 2018 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 29366866]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLieu JEC,Kenna M,Anne S,Davidson L, Hearing Loss in Children: A Review. JAMA. 2020 Dec 1; [PubMed PMID: 33258894]

Idstad M, Tambs K, Aarhus L, Engdahl BL. Childhood sensorineural hearing loss and adult mental health up to 43 years later: results from the HUNT study. BMC public health. 2019 Feb 8:19(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6449-2. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 30736854]

Ronner EA, Benchetrit L, Levesque P, Basonbul RA, Cohen MS. Quality of Life in Children with Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2020 Jan:162(1):129-136. doi: 10.1177/0194599819886122. Epub 2019 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 31684823]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAmerican Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007 Oct:120(4):898-921 [PubMed PMID: 17908777]

Moore DR, Anatomy and physiology of binaural hearing. Audiology : official organ of the International Society of Audiology. 1991; [PubMed PMID: 1953442]

Lieu JE, Tye-Murray N, Fu Q. Longitudinal study of children with unilateral hearing loss. The Laryngoscope. 2012 Sep:122(9):2088-95. doi: 10.1002/lary.23454. Epub 2012 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 22865630]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLieu JE. Speech-language and educational consequences of unilateral hearing loss in children. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2004 May:130(5):524-30 [PubMed PMID: 15148171]

Bagatto M, DesGeorges J, King A, Kitterick P, Laurnagaray D, Lewis D, Roush P, Sladen DP, Tharpe AM. Consensus practice parameter: audiological assessment and management of unilateral hearing loss in children. International journal of audiology. 2019 Dec:58(12):805-815. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2019.1654620. Epub 2019 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 31486692]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePickles JO, Auditory pathways: anatomy and physiology. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2015; [PubMed PMID: 25726260]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKanji A, Khoza-Shangase K, Moroe N. Newborn hearing screening protocols and their outcomes: A systematic review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2018 Dec:115():104-109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.09.026. Epub 2018 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 30368368]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLiming BJ, Carter J, Cheng A, Choo D, Curotta J, Carvalho D, Germiller JA, Hone S, Kenna MA, Loundon N, Preciado D, Schilder A, Reilly BJ, Roman S, Strychowsky J, Triglia JM, Young N, Smith RJ. International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG) consensus recommendations: Hearing loss in the pediatric patient. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Nov:90():251-258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.09.016. Epub 2016 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 27729144]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVignesh SS, Jaya V, Muraleedharan A. Prevalence and Audiological Characteristics of Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder in Pediatric Population: A Retrospective Study. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2016 Jun:68(2):196-201. doi: 10.1007/s12070-014-0759-6. Epub 2014 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 27340636]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceY S,R G,Y D,Bz J,S K,V N,M K, Predicting hearing loss in children according to the referrer and referral cause. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2020 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 31610440]

Bois E, Francois M, Benkerrou M, Van Den Abbeele T, Teissier N. Hearing loss in children with sickle cell disease: A prospective French cohort study. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2019 Jan:66(1):e27468. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27468. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30251366]

Johnston DR, Curry JM, Newborough B, Morlet T, Bartoshesky L, Lehman S, Ennis S, O'Reilly RC. Ophthalmologic disorders in children with syndromic and nonsyndromic hearing loss. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2010 Mar:136(3):277-80. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.13. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20231647]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRopers FG, Pham ENB, Kant SG, Rotteveel LJC, Rings EHHM, Verbist BM, Dekkers OM. Assessment of the Clinical Benefit of Imaging in Children With Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2019 May 1:145(5):431-443. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0121. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30946449]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYilmaz Çiftdogan D,Vardar F, Effect on hearing of oral valganciclovir for asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Journal of tropical pediatrics. 2011 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 20576693]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGeers AE, Nicholas JG, Sedey AL. Language skills of children with early cochlear implantation. Ear and hearing. 2003 Feb:24(1 Suppl):46S-58S [PubMed PMID: 12612480]

Sharma SD, Cushing SL, Papsin BC, Gordon KA. Hearing and speech benefits of cochlear implantation in children: A review of the literature. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2020 Jun:133():109984. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.109984. Epub 2020 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 32203759]

Geers AE, Brenner CA, Tobey EA. Long-term outcomes of cochlear implantation in early childhood: sample characteristics and data collection methods. Ear and hearing. 2011 Feb:32(1 Suppl):2S-12S. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182014c53. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21832885]

Cheung A,Chen T,Rivero R,Hartman-Joshi K,Cohen MB,Levi JR, Assessing Loss to Follow-up After Newborn Hearing Screening in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Sociodemographic Factors That Affect Completion of Initial Audiological Evaluation. Ear and hearing. 2021 Sep 14; [PubMed PMID: 34524152]