Introduction

Oral cutaneous fistula (OCF) is a rare extraoral path of infection that communicates the oral cavity and the skin.[1] In medical and dental literature, the terms fistulas and sinus tracts are often used to describe the same condition. Chronic dental infections, trauma, dental implant complications, salivary gland lesions, and neoplasms are the most common causes of oral cutaneous fistulas. Affected patients usually seek help from dermatologists or surgeons rather than from dentists. As the clinical manifestations of OCF are generally scarce and often nonspecific, the diagnosis of OCF requires a high degree of suspicion. Odontogenic cutaneous fistulas have an excellent prognosis when treatment initiates promptly. Otherwise, oral cutaneous fistulas associated with malignancies can lead to complications and may be life-threatening.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Odontogenic cutaneous fistulas are responsible for most cases of oral cutaneous fistulas reported in the literature.[2] They arise as sequelae to bacterial invasion of the dental pulp caused by a carious lesion, trauma, or other causes.[3] If the affected tooth is not treated, the pulp becomes necrotic, and the infection spreads into the periradicular area.[3] Most odontogenic fistulas open intraorally; however, chronic dental infections may slowly progress as an alveolar bone abscess.[4] When this inflammatory process leads to cortical bone and periosteum resorption, it extends to the surrounding soft tissue dissecting through the path of least resistance.[4] The infection spreads below the mylohyoid, mentalis, and buccinator muscles attachments in the mandible and above the buccinator muscle attachment in the maxilla.[5]

Cutaneous fistulas and sinuses in the maxillofacial region secondary to osteomyelitis rarely appear in clinical practice.[6] They are more likely to develop in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, in those with osteoradionecrosis who have undergone jaw irradiation, and in those with metabolic bone diseases such as osteitis deformans “Paget disease” or osteopetrosis.

An additional cause of oral cutaneous fistula is medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.[7] Bisphosphonates and other anti-resorptive medications, as well as intravenous antiangiogenic therapies, have been reported to induce osteonecrosis of the jaw.[7] These medications have roles in the treatment of diseases such as lytic bone metastases, malignant hypercalcemia, multiple myeloma, and osteoporosis.

Traumatic fistulas may be the result of injury or surgical repair. In a study by Dawson et al., which explored factors associated with the formation of orocutaneous fistulas following head and neck reconstructive surgery, they found that patients who had undergone chemoradiotherapy had a significantly higher probability of developing a fistula than those who had not (p = 0.008).[8]

Complications of dental implants usually result from a combination of infection and host inflammatory responses or a lack thereof. The literature reports a case report of an oral cutaneous fistula associated with an osseointegrated dentoalveolar implant which occurred after three months.[9]

There are also reports of fistulas mimicking a brachial cyst caused by an ectopic salivary gland. In one case, a 24-year-old man presented with intermittent clear drainage on both sides of the middle neck. The lesion underwent surgical excision, and the pathological examination revealed heterotopic salivary gland tissue.[10]

Periapical actinomycosis is among the rarest forms of actinomycosis in the maxillofacial region. Although rare, it can result in an orocutaneous fistula.[11]

More rarely, OCF is secondary to a neoplasm. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common oral cavity neoplasm. If the fistula occurs, it has a poor prognosis because lymphatic drainage has most likely taken place by the time of diagnosis.

Epidemiology

In the most extensive study of odontogenic cutaneous fistulas reported by Guevara-Gutiérrez et al., which examined 75 cases during an eleven-year timeframe, the mean age was 45. The most affected age group was 51 years old and over (28%). The female to male ratio was 1.14 to 1.[3] Many factors were suspected of inducing dental infections and facilitating the formation of sinus tracts, such as poor oral hygiene, xerostomia, and unsatisfactory surgical procedures. The mandibular teeth originated the fistulous tracts in 87% of cases.[3] In the study of Lee et al., the fistulas were related to actinomycosis in two of 33 patients. In one patient, the fistula was presumed to have been caused by osteoradionecrosis after radiation therapy for mandible cancer.[4]

Histopathology

The possibility of a neoplastic cause may require a histopathological examination of the oral cutaneous fistula. A biopsy is also helpful for diagnosing actinomycosis, which has characteristic pseudohyphae appearing as clublike projections that stretch out from a central basophilic staining core.[11]

History and Physical

Dental infection is the most common cause of cutaneous fistulas of the face.[2] In contrast with acute infections that provoke extreme pain, chronic dental infections are often asymptomatic. An odontogenic cutaneous fistula is an established entity not always associated with a history of pain, making its diagnosis challenging.[5] Patients usually report intermittent periods of resolution of the skin lesion [12] and a prior history of visiting many other clinicians without a precise diagnosis.[5] In a study by Lee and colleagues, 27 patients (81.8%) with odontogenic cutaneous fistulas were initially misdiagnosed, resulting in one or more recurrences.[4]

In the series of Guevara-Gutierrez et al., the authors found that the more frequent locations of odontogenic cutaneous fistula were the mandibular angle (36%), the chin (28%), and the cheeks (24%).[3] The location of the oral cutaneous fistula (OCF) was adjacent to the causative tooth in 99% of patients.[3] However, less common sites for the fistula were reported and should be considered when assessing a skin lesion of the face: internal canthus of the eye, arising from a second upper molar infection; wing of the nose, originating from an upper canine infection; neck, originating from a lower molar infection.[3]

The clinical aspect of the odontogenic cutaneous fistula on the skin varies but most commonly appears as a nodule.[3] Samir et al. described the classic odontogenic cutaneous fistula lesion as an erythematous, smooth, symmetric nodule of up to 2 cm in diameter, with or without drainage, and skin retraction due to healing.[13] It is worth noting that other possible skin manifestations include dimpling, abscesses, gummas, skin tracts, cysts, nodulocystic lesions with suppuration, scars, and ulcers.[3][14] This morphology variety emphasizes the need to assess the oral tissues when a skin lesion appears on the face and neck regions.[3]

Although rare, in some cases, the origin of the oral cutaneous fistula is not odontogenic. In chronic osteomyelitis with drainage, pain may not be a symptom. An intraoral sinus tract may be raised or appear as a red-to-yellow ulcer that bleeds easily and exudes pus. In some cases of actinomycosis, yellow granules are observable at clinical examination. Signs of salivary gland infections include swelling, pain, and trismus if the parotid gland is involved.

Evaluation

In the case of odontogenic cutaneous fistula, performing pulp sensitivity tests, percussion, and palpation helps identify the affected tooth.[5]

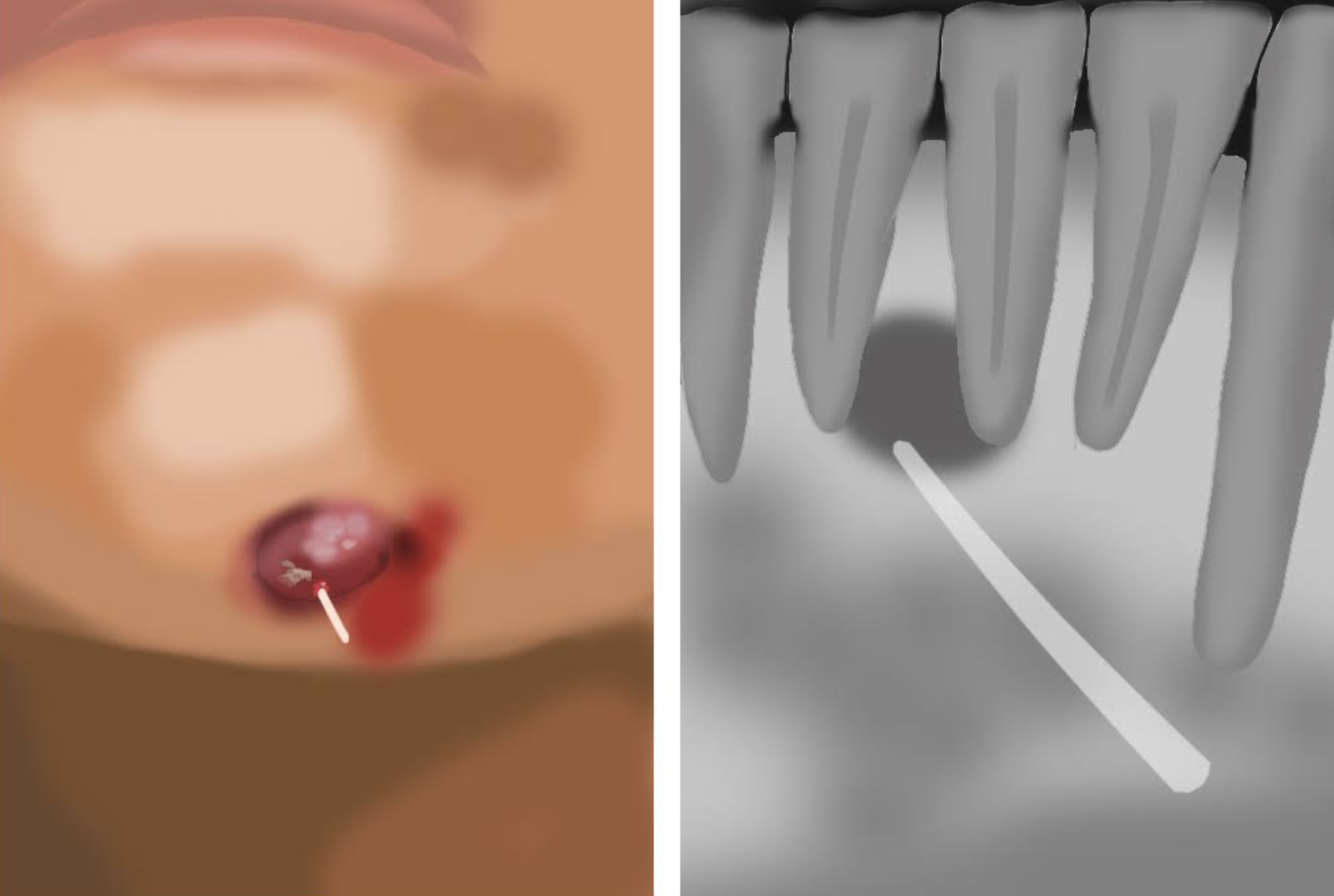

Radiographic examination is essential for diagnosing an odontogenic cutaneous fistula, for which a periapical x-ray, panoramic radiograph, or cone beam CT scan can be used.[3] The periapical bone loss will appear on the x-ray and aid in identifying the affected tooth.[15] A gutta-percha point is usually placed into the opening of the fistula before taking the x-ray to show the extension and source of the fistulous tract.[5]

Treatment / Management

Complete resolution of the fistula occurs after appropriate dental treatment of the causative tooth by either an endodontic treatment or a tooth extraction.[16] The fistula tends to heal via secondary intention without further therapy by two weeks.[16] (B3)

A residual skin scar in the form of dimpling or hyperpigmentation usually improves with time but, it may remain after a few months.[12][4] Surgical management of the scar may be needed for cosmetic reasons.[16](B3)

In a study by Andrews et al., the authors reported the beneficial use of a negative-pressure vacuum-assisted closure technique (VAC) to facilitate the closure of oral cutaneous fistula (OCF).[17](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Because orocutaneous fistulas (OCF) are uncommon, misdiagnosis of those from a dental origin is not unusual. In the study of Lee et al., the majority of patients were misdiagnosed initially. Oral cutaneous fistulas were thought to be an epidermal cyst (24,2%), furuncle (21.2%), subcutaneous mycosis (15.2%), squamous cell carcinoma (9.1%), basal cell carcinoma (6.1%), and foreign body granuloma (6.1%).[4] The differential diagnosis include tuberculosis infection, pyogenic granuloma, suppurative lymphadenitis, salivary gland fistula, and carcinoma.[1]

Prognosis

Odontogenic cutaneous fistulas have a very good prognosis after treating the offending tooth, where they usually resolve themselves without more interventions. However, they often leave a scar that needs to be managed surgically to improve the aesthetic appearance.[16]

Complications

Around 50% of patients with odontogenic cutaneous fistulas of the face and neck are initially misdiagnosed,[3] leading to unnecessary investigations and treatments. These patients endure biopsies, skin surgeries, chronic antibiotic therapy, and, in some cases, even radiotherapy before a dental cause is established.[3] When not diagnosed in time, fistulas may leave unpleasant scars.[12]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The most effective preventive measure against oral cutaneous fistula (OCF) is oral hygiene. Preventative measures against dental caries and thus dentoalveolar abscess are tooth brushing, flossing, and fluoridation of communal drinking water. A regular dental check-up should be done. In case of a toothache or dental abscess, immediately consult a dentist.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An oral cutaneous fistula frequently poses a diagnostic dilemma. These patients may exhibit non-specific symptoms and highly variable skin lesion morphology, leading to confusion. Although poorly recognized, chronic dental infection is the most common cause of cutaneous fistulas of the face and neck.[6][7][9][11] Dermatologists tend to be consulted since OCFs open into the skin, usually as a nodule or dimpling. It is important to consult with a dentist to assess the oral cavity, rule out a dental origin of the infection, and avoid delays in treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ohta K, Yoshimura H. Odontogenic cutaneous fistula of the face. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2019 Nov 18:191(46):E1281. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190674. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31740538]

Figaro N, Juman S. Odontogenic Cutaneous Fistula: A Cause of Persistent Cervical Discharge. Case reports in medicine. 2018:2018():3710857. doi: 10.1155/2018/3710857. Epub 2018 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 29991948]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuevara-Gutiérrez E, Riera-Leal L, Gómez-Martínez M, Amezcua-Rosas G, Chávez-Vaca CL, Tlacuilo-Parra A. Odontogenic cutaneous fistulas: clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of 75 cases. International journal of dermatology. 2015 Jan:54(1):50-5. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12262. Epub 2013 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 24134798]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee EY, Kang JY, Kim KW, Choi KH, Yoon TY, Lee JY. Clinical Characteristics of Odontogenic Cutaneous Fistulas. Annals of dermatology. 2016 Aug:28(4):417-21. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.4.417. Epub 2016 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 27489421]

Kelly MS, Murray DJ. Surgical management of an odontogenic cutaneous fistula. BMJ case reports. 2021 Mar 16:14(3):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-240306. Epub 2021 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 33727295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoche E, García-Melgares ML, Laguna C, Martín-González B, Fortea JM. [Chronic cutaneous fistula secondary to mandibular osteomyelitis]. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2006 Apr:97(3):203-5 [PubMed PMID: 16796969]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, O'Ryan F, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw--2014 update. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2014 Oct:72(10):1938-56. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031. Epub 2014 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 25234529]

Dawson C, Gadiwalla Y, Martin T, Praveen P, Parmar S. Factors affecting orocutaneous fistula formation following head and neck reconstructive surgery. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2017 Feb:55(2):132-135. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.07.021. Epub 2016 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 27502876]

Mahmood R, Puthussery FJ, Flood T, Shekhar K. Dental implant complications - extra-oral cutaneous fistula. British dental journal. 2013 Jul:215(2):69-70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.683. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23887526]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOgawa K, Kondoh K, Kanaya K, Ochi A, Sakamoto T, Yamasoba T. Bilateral cervical fistulas from heterotopic salivary gland tissues. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 2014:76(6):336-41. doi: 10.1159/000369625. Epub 2015 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 25591615]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePasupathy SP, Chakravarthy D, Chanmougananda S, Nair PP. Periapical actinomycosis. BMJ case reports. 2012 Aug 1:2012():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006218. Epub 2012 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 22854234]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBorbon C, Gallesio C, Ramieri G. Odontogenic Cutaneous Fistula: A Case in Aged Patient With Delayed Diagnosis. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2021 Jun 1:32(4):e340-e342. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007114. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33038169]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSamir N, Al-Mahrezi A, Al-Sudairy S. Odontogenic Cutaneous Fistula: Report of two cases. Sultan Qaboos University medical journal. 2011 Feb:11(1):115-8 [PubMed PMID: 21509218]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSpear KL, Sheridan PJ, Perry HO. Sinus tracts to the chin and jaw of dental origin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1983 Apr:8(4):486-92 [PubMed PMID: 6853781]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWitherow H, Washan P, Blenkinsopp P. Midline odontogenic infections: a continuing diagnostic problem. British journal of plastic surgery. 2003 Mar:56(2):173-5 [PubMed PMID: 12791368]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCioffi GA, Terezhalmy GT, Parlette HL. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenic etiology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1986 Jan:14(1):94-100 [PubMed PMID: 3950118]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAndrews BT, Smith RB, Hoffman HT, Funk GF. Orocutaneous and pharyngocutaneous fistula closure using a vacuum-assisted closure system. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2008 Apr:117(4):298-302 [PubMed PMID: 18478840]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence