Introduction

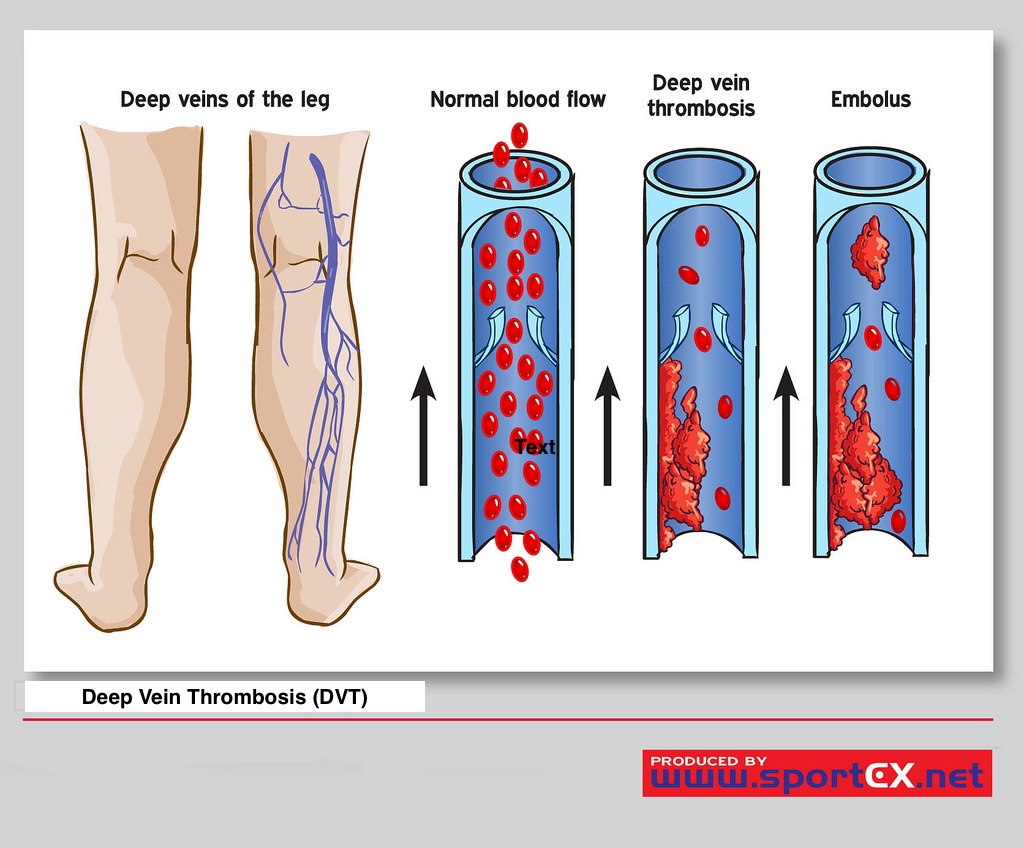

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is an obstructive disease with a hindering venous reflux mechanism.[1] DVT usually involves the lower limb venous system, with clot formation originating in a deep calf vein and propagating proximally.[2] See Image. Deep Vein Thrombosis. It is a common venous thromboembolic (VTE) disorder with an incidence of 1.6 per 1000 annually.[3] The rate of particular site involvement depends on the anatomical location as follows, distal veins 40%, popliteal 16%, femoral 20%, common femoral 20%, and iliac veins 4%.[4]

A deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot that forms within the deep veins, usually of the leg, but can occur in the arms and the mesenteric and cerebral veins. Deep-vein thrombosis is a common and important disease. It is part of the venous thromboembolism disorders, representing the third most common cause of death from cardiovascular disease after heart attacks and stroke. Even in patients who do not get pulmonary emboli, recurrent thrombosis and "post-thrombotic syndrome" are major causes of morbidity.[5][6][7] Deep-vein thrombosis is a major medical problem accounting for most cases of pulmonary embolism. Only through early diagnosis and treatment can the morbidity be reduced.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Risk Factors

Following are the risk factors that are considered causes of deep venous thrombosis:

- Reduced blood flow: Immobility (bed rest, general anesthesia, operations, stroke, long flights)[8][9]

- Increased venous pressure: Mechanical compression or functional impairment leading to reduced flow in the veins (neoplasm, pregnancy, stenosis, or congenital anomaly which increases outflow resistance)[10]

- Mechanical injury to the vein: Trauma, surgery, peripherally inserted venous catheters, previous DVT, intravenous drug abuse [11][12][11]

- Increased blood viscosity: Polycythaemia rubra vera, thrombocytosis, dehydration [13]

- Anatomic variations in venous anatomy can contribute to thrombosis

Increased Risk of Coagulation

- Genetic deficiencies: Anticoagulation proteins C and S, antithrombin III deficiency, factor V Leiden mutation [14][15][16]

- Acquired: Cancer, sepsis, myocardial infarction, heart failure, vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus anticoagulant, inflammatory bowel disease, nephrotic syndrome, burns, oral estrogens, smoking, hypertension, diabetes [12][17]

Constitutional Factors

Obesity, pregnancy, the advanced age of older than 60, surgery, critical care admission, dehydration, and cancer are the established causalities of DVT and VTE.[18][19][20][21] Obesity is associated with a hypercoagulability status via two mechanisms, 1. increased fibrinogen levels that may even surpass twofold the normal value, and 2. slower venous circulation flow in the infra diaphragmatic and especially in the lower limbs.[20] Both factors, associated with disorders in several coagulation factors, favor the appearance of venous thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, and thromboembolic events, and mostly fatal pulmonary thromboembolisms (PE), which are the primary cause of mortality in obese patients.[20]

Potential risk factors of deep vein thrombosis might be categorized according to the transient, persistent, or unprovoked criteria. Accordingly, transient risk factors are as follows: 1. surgery with general anesthetics, 2. hospitalization, 3. Cesarean section, 4. hormone replacement therapy, 5. pregnancy and peripartum period, 6. lower extremity injury with limited mobility for more than 72 hours.[4] It should be noted that general anesthesia for longer than 30 minutes and hospitalization for longer than 72 hours are considered the transient risk factors of DVT.[4] However, active cancers and specific medical conditions that increase the risk of venous thromboembolism are categorized as persistent risk factors. Systemic lupus erythematosus and inflammatory bowel disease are among the predisposing medical conditions.[4]

Any further etiological risk factors not categorized among either transient or persistent subgroups should be labeled as unprovoked VTE.[4][1] For instance, a recent cohort study, including 500 participants evaluating the association of blood lipid levels and lower extremity DVT (LEDVT), demonstrated that higher total cholesterol levels, high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C), and apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) were associated with a decreased risk of lower extremity DVT (LEDVT). However, higher triglyceride levels (TG) were associated with a greater risk of LEDVT.[1]

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence: Deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli are common and often "silent" and thus go undiagnosed or are only picked up at autopsy. Therefore, the incidence and prevalence are often underestimated. It is thought the annual incidence of DVT is 80 cases per 100,000, with a prevalence of lower limb DVT of 1 case per 1000 population.[1] Annually in the United States, more than 200,000 people develop venous thrombosis; of those, 50,000 cases are complicated by pulmonary embolism.[22][23][24]

- Age: Deep-vein thrombosis is rare in children, and the risk increases with age, most occurring in the over-40 age group.[1]

- Gender: There is no consensus about whether there is a sex bias in the incidence of DVT.

- Ethnicity: There is evidence from the United States that there is an increased incidence of DVT and an increased risk of complications in African Americans and white people compared to Hispanic and Asian populations.

- Associated diseases: In the hospital, the most commonly associated conditions are malignancy, congestive heart failure, obstructive airway disease, and patients undergoing surgery.

Pathophysiology

According to the Virchow triad, the following are the main pathophysiological mechanisms involved in DVT:

- Damage to the vessel wall

- Blood flow turbulence

- Hypercoagulability

Thrombosis is a protective mechanism that prevents the loss of blood and seals off damaged blood vessels. Fibrinolysis counteracts or stabilizes thrombosis. The triggers of venous thrombosis are frequently multifactorial, with the different parts of the triad of Virchow contributing in varying degrees in each patient, but all result in early thrombus interaction with the endothelium. This stimulates local cytokine production and causes leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium, promoting venous thrombosis. Depending on the relative balance between the coagulation and thrombolytic pathways, thrombus propagation occurs. DVT is commonest in the lower limb below the knee and starts at low-flow sites, such as the soleal sinuses, behind venous valve pockets.[25][26][27] A potential correlation between DVT and atherosclerosis (AS) has been proposed.[1] The endothelial dysfunction involved in the pathophysiological mechanism of DVT would potentially result in AS. Accordingly, a greater risk of subsequent AS in patients with DVT is predicted.[1]

Histopathology

In the venous system following acute thrombosis formation, an extensive remodeling process occurs. Neutrophils and macrophages infiltrate the fibrin clot from within the lumen of the vessel over weeks leading to cytokine release and, eventually, fibroblast and collagen replacement of fibrin. This remodeling and fibrosis can result in diminished blood flow long after the acute thrombosis resolves.[28]

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of acute lower extremity DVT varies with the anatomic distribution, extent, and degree of occlusion of the thrombus. Symptoms may range from absence to massive swelling and cyanosis with impending venous gangrene. Three patterns of thrombosis are usually recognized: isolated calf vein (distal), femoropopliteal, and iliofemoral thrombosis, and symptoms tend to be more severe as thrombosis extends more proximally (see Video. Popliteal Deep Vein Thrombosis With Partial Color Flow, Video). However, up to 50% of patients with acute DVT may lack specific signs or symptoms. [5][6] Postoperative patients are, in particular, more likely to have small, asymptomatic, distal, non-occlusive thrombi. When present, signs and symptoms of acute lower extremity DVT may include pain, edema, erythema, tenderness, fever, prominent superficial veins, pain with passive dorsiflexion of the foot (Homan’s sign), and peripheral cyanosis. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, characterized by the triad of massive swelling, cyanosis, and pain, is the most severe form of acute lower extremity DVT and results from complete thrombosis of an extremity’s venous outflow.[7] In advanced cases, it is marked by severe venous hypertension with collateral and microvascular thrombosis, leading to venous gangrene. Venous gangrene is particularly associated with warfarin-mediated protein C depletion in patients with cancer or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.[8][9]

Obtaining the diagnosis of DVT only based on clinical signs and symptoms is notoriously inaccurate. The signs and symptoms of DVT are generally non-specific. They may be associated and misdiagnosed with other lower extremity disorders. Accordingly, lymphedema, superficial venous thrombosis, and cellulitis should be excluded. However, the most common presenting symptoms with inconsistent sensitivity and specificity are calf pain and swelling. The former index has a sensitivity of 75% to 91% and a specificity of 3% to 87%, and the latter might have a sensitivity of up to 97% and a specificity of up to 88%.[29] None of the signs or symptoms is sufficiently sensitive or specific, either alone or in combination, to accurately diagnose or exclude thrombosis.[30]

History

- Pain (50% of patients)

- Redness

- Swelling (70% of patients)

Physical Examination

- Limb edema (may be unilateral or bilateral if the thrombus extends to pelvic veins)

- Red and hot skin with dilated veins

- Tenderness

Evaluation

The following veins are categorized as deep veins according to the Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology (CEAP) classification: 1. inferior vena cava, 2. common iliac, 3. internal and external iliac, 4. pelvic veins, including a. gonadal, and b. broad ligament veins, 5. common femoral, 6. deep femoral vein, 7. femoral, 8. popliteal, 9. paired crural veins of anterior and posterior tibial and peroneal, 10. muscular veins of gastrocnemial, and soleal.[31]

As per the National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines following investigations are done:

- D-dimers (very sensitive but not very specific)

- Coagulation profile

- Proximal leg vein ultrasound, which, when positive, indicates that the patient should be treated as having a DVT

Deciding how to investigate is determined by the risk of DVT. The first step is to assess the clinical probability of a DVT using the Wells scoring system.

- The clinical probability is low for patients with a score of 0 to 1, but for those with two or above, the clinical probability is high.

- If a patient scores 2 or above, either a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan should be done within 4 hours, and if the result is negative, a D-dimer test should be done. If imaging is not possible within 4 hours, a D-dimer test should be undertaken, and an interim 24-hour dose of a parenteral anticoagulant should be given. A proximal leg vein ultrasound scan should be carried out within 24 hours of being requested.

- In the case of a positive D-dimer test and a negative proximal leg vein ultrasound scan, the proximal leg vein ultrasound scan should be repeated 6 to 8 days later for all patients.

- If the patient does not score 2 on the DVT Wells score, but the D-dimer test is positive, the patient should have a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan within 4 hours, or if this is not possible, the patient should receive an interim 24-hour dose of a parenteral anticoagulant. A proximal leg vein ultrasound scan should be carried out within 24 hours of being requested.

- In all patients diagnosed with DVT, treat as if there is a positive proximal leg vein ultrasound scan.[32][33][34]

Clinical decision rules such as the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) and the Wells Criteria should be employed with the patient presenting with a possible DVT. Risk stratification is crucial in deciding diagnostic and management options. Patients who meet PERC criteria may need no further testing, whereas those who do not meet PERC criteria and are low probability based on the Wells criteria may be candidates for rule-out with a D-dimer. The D-dimer test is sensitive but not specific and should be used selectively in a low-probability patient who does not have other confounding diagnoses that could produce a false positive test. The test also should be used with caution, perhaps with different cut-off values in the elderly.[5][6][7][8]

Imaging modalities available to evaluate for DVT include diagnostic ultrasound, vascular studies, CT venograms, and point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). The POCUS exam is described below. Rapid diagnosis or rule-out by the emergency provider can expedite necessary treatment and reduce the length of stay, and it is particularly useful when access to 24-hour ultrasound is unavailable. There is evidence that emergency practitioners can perform a two-point compression exam at the two highest probability sites for identifying a DVT: femoral and popliteal veins. However, recent literature suggests a 2-region approach where clinicians do serial compression testing may significantly improve diagnostic sensitivity without greatly increasing diagnostic time. This point-of-care ultrasound exam should be used with other clinical decision rules and is perhaps most useful in those patients with high and low pre-test probability.

With the patient supine in the frog-leg position, apply approximately 20 to 30 degrees of reverse Trendelenburg to increase venous distention. Place the high-frequency linear transducer (5 to 10 MHz) in the transverse plane at the anatomical location of the inguinal ligament. Just distal to the inguinal ligament, the common femoral vein can be visualized. Apply direct pressure to the vein. The complete collapse of the vein indicates there is no presence of a DVT. Continue distally along the femoral vein to where the greater saphenous vein and deep femoral vein deviate from the common femoral vein. Complete compression of all venous structures at these levels rules out a proximal DVT.

Next, proceed to the popliteal region. Laterally rotate the leg, flex the knee, and place the high-frequency transducer transversely in the popliteal fossa. The popliteal vein typically resides just anterior to the popliteal artery. Apply a compressive force once again and observe for complete compression. Compress the areas just proximal and distal to the popliteal fossa as well to complete the two-region technique. If DVT studies are negative, repeat testing may be required in one to two weeks to rule out a propagating calf DVT further. Alternatively, sending a D-dimer test may be adequate in certain patient populations. Typical laboratory tests also should be sent to evaluate for coagulation status, blood count, and renal function.[9][10][35]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of DVT aims to prevent pulmonary embolism, reduce morbidity, and prevent or minimize the risk of developing post-thrombotic syndrome. The cornerstone of treatment is anticoagulation. NICE guidelines only recommend treating proximal DVT (not distal) and those with pulmonary emboli. In each patient, the risks of anticoagulation need to be weighed against the benefits.[36][37][38] Treatment for DVT should be addressed mainly according to the underlying causality of DVT as follows:(B3)

- The preferred anticoagulant to address DVT in cancer-associated thromboembolism is low molecular weight heparin and factor Xa inhibitors, including rivaroxaban.[39] However, in the following circumstances, the higher levels of anticoagulation should be considered: 1. recently diagnosed cancer, 2. extensive VTE circumstances, and 3. cancer treatment-related adverse effects, including vomiting.[40]

- In circumstances where once-daily oral therapy is the preferred management, the following options are viable; 1. rivaroxaban, 2. edoxaban, and 3. vitamin-K antagonist (VKA)

- In the context of liver disease, DVT should be managed with low-molecular-weight heparin.[41] Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are contraindicated in raised INR levels.

- In patients with renal disease suppressed creatinine clearance to less than 30 ml/min, VKAs are recommended. DOACs and LMWH should be avoided in patients with end-stage renal disease.

- In patients with a remarkable past medical history of coronary artery disease, the following alternatives are recommended: 1. VKA, 2. rivaroxaban, 3. apixaban, and 4. edoxaban.[42]

- In patients with remarkable dyspepsia or any past medical history suggestive of gastrointestinal bleeding, VKA, and apixaban are the preferred treatments. It should be noted that DOCAs, eg, dabigatran, factor Xa inhibitors, eg, rivaroxaban, and selective factor Xa inhibitors, eg, edoxaban, might be associated with higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding.[43][44][45]

- In the group of patients with a history compatible with poor compliance, VKA is preferred. However, it should be noted that some patients might still be highly compliant with other alternatives, including DOACs.[46]

- If thrombolytic therapy is indicated, unfractionated heparin is indicated.[47]

- In patients who might later be subjected to reversal of thrombolytic therapy, it should be noted that reversal agents for DOACs are not universally available.

- Since most anticoagulants have the potential to cross the placenta, the preferred anticoagulation therapy during pregnancy is LMWH. (A1)

Moreover, the following guidelines address the required duration of treatment.

- Prescribe low-molecular-weight heparin or fondaparinux for 5 days or until the international normalized ratio (INR) is greater than 2 for 24 hours (unfractionated heparin for patients with renal failure and increased risk of bleeding).

- Supplement with vitamin K antagonists for 3 months.

- In patients with cancer, consider anticoagulation for 6 months with low-molecular-weight heparin.

- In patients with unprovoked DVT, consider vitamin K antagonists beyond 3 months.

- Rivaroxaban is an oral factor Xa inhibitor that has recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and NICE and is attractive because there is no need for regular INR monitoring.

- If the platelet count drops to less than 75,000, switch from heparin to fondaparinux, which is not associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Thrombolysis: The indications for the use of thrombolytics include:

- Symptomatic iliofemoral DVT

- Symptoms of less than 14 days duration

- Good functional status

- A life expectancy of 1 year or more

- Low risk of bleeding

The use of thrombolytic therapy can result in an intracranial bleed, and hence, careful patient selection is vital. Recently endovascular interventions like catheter-directed extraction, stenting, or mechanical thrombectomy have been tried with moderate success.

- Compression hosiery: Below-knee graduated compression stockings with an ankle pressure greater than 23 mm Hg for 2 years if there are no contraindications

- Inferior vena cava filters: If anticoagulation is contraindicated or if emboli are occurring despite adequate anticoagulation

Newer Drugs

Rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and betrixaban are relatively newer factor Xa inhibitors approved for prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis. The duration of DVT treatment is 3 to 6 months, but recurrent episodes may require at least 12 months of treatment. Patients with cancer need long-term treatment. Inferior vena cava filters are not recommended in acute DVT. There are both permanent and temporary inferior vena cava filters available. These devices may decrease the rate of recurrent DVT but do not affect survival. Today, only patients with contraindications to anticoagulation with an increased risk of bleeding should have these filters inserted.

Differential Diagnosis

The following are differential diagnoses of deep venous thrombosis:

- Cellulitis

- Post-thrombotic syndrome (especially venous eczema and lipodermatosclerosis)

- Ruptured Baker cyst

- Trauma

- Superficial thrombophlebitis

- Peripheral edema, heart failure, cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome

- Venous or lymphatic obstruction

- Arteriovenous fistula and congenital vascular abnormalities

- Vasculitis [35]

Surgical Oncology

Given the increased risk of thromboembolism, patients with clinically active malignancy would benefit from thromboprophylaxis. A meta-analysis looking at a total of 33 trials and 11,972 patients provided more evidence that thromboprophylaxis decreased the incidence of VTE in cancer patients who were undergoing chemotherapy or surgery, with no apparent increase in the incidence of significant bleeding.[7] Current guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin in hospitalized cancer patients as thromboprophylaxis. Mechanical prophylaxis should be used instead of anticoagulation therapy in patients experiencing active bleeding, thrombocytopenia (platelet count below 50,000/MCL), evidence of hemorrhagic coagulopathy, or having an indwelling neuraxial catheter. Contraindications to mechanical prophylaxis include acute deep venous thrombosis and severe arterial insufficiency.

A recent meta-analysis addressed the question of the optimum duration of anticoagulation in cancer patients hospitalized with acute illnesses. This study looked at trials comparing standard-duration versus extended-duration anticoagulation prophylaxis. The risk of VTE was not significantly lower in the extended-duration prophylaxis group of patients, but the risk of bleeding was about 2-fold higher.[8] Regarding outpatient VTE prophylaxis, surgical pelvic or abdominal oncology patients would benefit from continuing VTE prophylaxis up to four weeks post-operation. The use of aspirin or anticoagulation therapy for patients with multiple myeloma on immunomodulatory medications is recommended based on risk stratification with the IMPEDE VTE score.[9][10] For patients with solid cancers on chemotherapy and high Khorana score, prophylactic anticoagulation with direct oral anticoagulation or low molecular weight heparin showed a decrease in the incidence of pulmonary embolism.[11]

Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) remains the preferred anticoagulation option for managing cancer-associated thrombosis.[12] The dosage recommendation for LMWH is 1 mg/kg every 12 hours and 1 mg/kg once daily for patients with creatinine clearance of less than 30 mL/minute. Avoid the use of LMWH in patients on dialysis. Other treatment options include direct oral anticoagulants like apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, fondaparinux, and warfarin. In the Caravaggio trial, researchers found apixaban to be non-inferior to LMWH in treating cancer-associated VTE without an increased risk of significant bleeding.[13]

Thrombolytic therapy can be used in patients with life or limb-threatening pulmonary embolism or acute deep vein thrombosis considering contraindications such as intracranial tumors or metastasis, active bleeding, and a history of intracranial hemorrhage. NCCN recommends a treatment duration minimum of 3 months or for the duration of active malignancy. For patients with non-catheter-related deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, indefinite anticoagulation is the recommendation.

Continuing to assess for benefits vs. risks, as well as monitoring for complications, is essential. In patients with DVT located in the inferior vena cava, iliac, femoral, and popliteal veins, in addition to a contraindication to therapeutic anticoagulation, placement of retrievable vena cava filters can prevent pulmonary embolism. Once placed, it is important to periodically assess patients for resolution of contraindications, removal of the vena cava filters, and switching to therapeutic anticoagulation. For patients with catheter-associated thrombosis, treatment consists of removing the catheter or anticoagulation if the catheter remains.[10]

Staging

The severity of the disease is classified as follows:

- Provoked: Due to acquired states (surgery, oral contraceptives, trauma, immobility, obesity, cancer)

- Unprovoked: Due to idiopathic or endogenous reasons; more likely to suffer recurrence if anticoagulation is discontinued

- Proximal: Above the knee, affecting the femoral or iliofemoral veins; much more likely to lead to complications such as pulmonary emboli

- Distal: Below the knee

Prognosis

The prognosis for DVT includes the following:

- Many DVTs will resolve with no complications.

- Post-thrombotic syndrome occurs in 43% of patients 2 years post-DVT (30% mild, 10% moderate, and severe 3%).

- The risk of recurrence of DVT is high (up to 25%).

- Death occurs in approximately 6% of DVT cases and 12% of pulmonary embolism cases within one month of diagnosis.

- Early mortality after venous thromboembolism is strongly associated with the presentation of pulmonary embolism, advanced age, cancer, and underlying cardiovascular disease.

Complications

The following are the 2 major complications of DVT:

- Pulmonary emboli (paradoxical emboli if an atrial-septal defect is present)

- Post-thrombotic syndrome

- Bleeding from the use of anticoagulants

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Thromboprophylaxis strategies for hospitalized patients at potential risk for deep vein thrombosis include pharmacological and mechanical arms. In the pharmacological aspect, unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparins, novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), such as direct thrombin binders, including dabigatran, factor Xa direct binders, including rivaroxaban, and aspirin or warfarin should be considered.[20][48][49] It should be noted that the results from network meta-analysis indicate that NOACs are an effective treatment for thromboprophylaxis of VTE or VTE-related mortality) in the extended treatment scenarios. However, the complication with bleeding risk differs. Accordingly, apixaban was reported to have the most favorable profile. The comparison was published in the context of other NOACs, warfarin with endpoints of INR 2.0 to 3.0, and aspirin.[49][50][51]

In the mechanical prophylactic arm, the following measures should be evaluated;

- Graduated compression stockings

- Intermittent pneumatic compression devices

- Venous foot pumps

- Electrical stimulation devices

Still, mechanical devices should be applied in conjunction with pharmacological prophylaxis.[20]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated on the following:

- Ambulation

- Wearing compression stockings

- Discontinuing smoking

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Deep-vein thromboses can occur in many settings and almost every medical specialty; failing to diagnose DVT can result in a pulmonary embolus, which can be fatal. DVTs also result in more prolonged admission to the hospital and drug treatment that can last 3 to 9 months, all of which add to the cost of healthcare. Thus its diagnosis and management are best made with an interprofessional healthcare team consisting of clinicians, specialists, nurses, physical therapists, vascular technicians, and pharmacists.

The focus is on the prevention of DVT. In addition to clinicians, both nurses and pharmacists are vital in educating patients about DVT prophylaxis. Nurses are the first professionals to encounter patients being admitted to the hospital, and it is here that the prevention of DVT starts. Nurses must educate the patients on the importance of ambulation, complying with compression stockings, and taking the prescribed anticoagulation medications. In both the operating room and post-surgery, nurses play a key role in reminding physicians of the need for DVT prophylaxis. Each hospital has guidelines on DVT prophylaxis and treatment, and all healthcare workers should follow them.

Once a DVT has developed, the pharmacist should be familiar with the current anticoagulants and their indications. They can consult with the prescribing/ordering clinician and perform medication reconciliation. Plus, the pharmacist must educate the patients on the need for treatment compliance and the need to undergo regular testing to ensure that the INR is therapeutic.[37][52] Once DVT is diagnosed, the treatment is with an anticoagulant for 3 to 6 months, and again, monitoring of the INR by a hematology nurse or pharmacist is necessary. Further, these patients need to be monitored for bleeding. Open communication between the interprofessional team is the only way to treat DVT and lower the morbidity of the drugs safely.

Outcomes

Nearly 300,000 patients die from a pulmonary embolus yearly in the US alone. Despite countless guidelines and education of healthcare workers, DVT prophylaxis is often not done. The fact is that DVT is preventable in the majority of patients, and the onus is on healthcare workers to be aware of the condition. For those who develop a DVT and survive, post-thrombotic phlebitis is a lifelong sequela with no ideal treatment.[53][54] This is why interprofessional care coordination and open communication is crucial to managing these patients long-term.

Media

(Click Video to Play)

Deep Vein Thrombosis. This illustration compares normal blood flow with that of deep vein thrombosis and embolism within the deep veins of the leg.

Contributed by M Schick, DO

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Huang Y, Ge H, Wang X, Zhang X. Association Between Blood Lipid Levels and Lower Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Clinical and applied thrombosis/hemostasis : official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2022 Jan-Dec:28():10760296221121282. doi: 10.1177/10760296221121282. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36189865]

Chen R, Feng R, Jiang S, Chang G, Hu Z, Yao C, Jia B, Wang S, Wang S. Stent patency rates and prognostic factors of endovascular intervention for iliofemoral vein occlusion in post-thrombotic syndrome. BMC surgery. 2022 Jul 12:22(1):269. doi: 10.1186/s12893-022-01714-9. Epub 2022 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 35831845]

Albricker ACL, Freire CMV, Santos SND, Alcantara ML, Saleh MH, Cantisano AL, Teodoro JAR, Porto CLL, Amaral SID, Veloso OCG, Petisco ACGP, Barros FS, Barros MVL, Souza AJ, Sobreira ML, Miranda RB, Moraes D, Verrastro CGY, Mançano AD, Lima RSL, Muglia VF, Matushita CS, Lopes RW, Coutinho AMN, Pianta DB, Santos AASMDD, Naves BL, Vieira MLC, Rochitte CE. Joint Guideline on Venous Thromboembolism - 2022. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. 2022 Apr:118(4):797-857. doi: 10.36660/abc.20220213. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35508060]

Stubbs MJ, Mouyis M, Thomas M. Deep vein thrombosis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2018 Feb 22:360():k351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k351. Epub 2018 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 29472180]

Parker K, Thachil J. The use of direct oral anticoagulants in chronic kidney disease. British journal of haematology. 2018 Oct:183(2):170-184. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15564. Epub 2018 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 30183070]

Naringrekar H, Sun J, Ko C, Rodgers SK. It's Not All Deep Vein Thrombosis: Sonography of the Painful Lower Extremity With Multimodality Correlation. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2019 Apr:38(4):1075-1089. doi: 10.1002/jum.14776. Epub 2018 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 30171620]

Seifi A, Dengler B, Martinez P, Godoy DA. Pulmonary embolism in severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2018 Nov:57():46-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.08.042. Epub 2018 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 30154000]

Belcaro G, Cornelli U, Dugall M, Hosoi M, Cotellese R, Feragalli B. Long-haul flights, edema, and thrombotic events: prevention with stockings and Pycnogenol® supplementation (LONFLIT Registry Study). Minerva cardioangiologica. 2018 Apr:66(2):152-159. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4725.17.04577-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29512362]

Liu Z, Tao X, Chen Y, Fan Z, Li Y. Bed rest versus early ambulation with standard anticoagulation in the management of deep vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2015:10(4):e0121388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121388. Epub 2015 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 25860350]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePrins MH, Lensing AW, Brighton TA, Lyons RM, Rehm J, Trajanovic M, Davidson BL, Beyer-Westendorf J, Pap ÁF, Berkowitz SD, Cohen AT, Kovacs MJ, Wells PS, Prandoni P. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. The Lancet. Haematology. 2014 Oct:1(1):e37-46. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(14)70018-3. Epub 2014 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 27030066]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRuskin KJ. Deep vein thrombosis and venous thromboembolism in trauma. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2018 Apr:31(2):215-218. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000567. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29334497]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, Garvey WT, Joffe AM, Kim J, Kushner RF, Lindquist R, Pessah-Pollack R, Seger J, Urman RD, Adams S, Cleek JB, Correa R, Figaro MK, Flanders K, Grams J, Hurley DL, Kothari S, Seger MV, Still CD. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures - 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2020 Feb:16(2):175-247. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.10.025. Epub 2019 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 31917200]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVayá A, Suescun M. Hemorheological parameters as independent predictors of venous thromboembolism. Clinical hemorheology and microcirculation. 2013:53(1-2):131-41. doi: 10.3233/CH-2012-1581. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22954636]

Senst B, Tadi P, Basit H, Jan A. Hypercoagulability. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855839]

Wypasek E, Undas A. Protein C and protein S deficiency - practical diagnostic issues. Advances in clinical and experimental medicine : official organ Wroclaw Medical University. 2013 Jul-Aug:22(4):459-67 [PubMed PMID: 23986205]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee SY, Niikura T, Iwakura T, Sakai Y, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Thrombin-antithrombin III complex tests. Journal of orthopaedic surgery (Hong Kong). 2017 Jan 1:25(1):170840616684501. doi: 10.1177/0170840616684501. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28418276]

Mori S, Ogata F, Tsunoda R. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with Janus kinase inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis: case presentation and literature review. Clinical rheumatology. 2021 Nov:40(11):4457-4471. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05911-4. Epub 2021 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 34554329]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEdens C, Rodrigues BC, Lacerda MI, Dos Santos FC, De Jesús GR, De Jesús NR, Levy RA, Leatherwood C, Mandel J, Bermas B. Challenging cases in rheumatic pregnancies. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2018 Jul 1:57(suppl_5):v18-v25. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key172. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30137591]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchmaier AA, Ambesh P, Campia U. Venous Thromboembolism and Cancer. Current cardiology reports. 2018 Aug 20:20(10):89. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-1034-3. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30128839]

Goktay AY, Senturk C. Endovascular Treatment of Thrombosis and Embolism. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2017:906():195-213 [PubMed PMID: 27664152]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhang W, Liu X, Cheng H, Yang Z, Zhang G. Risk factors and treatment of venous thromboembolism in perioperative patients with ovarian cancer in China. Medicine. 2018 Aug:97(31):e11754. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011754. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30075594]

Hansen AT, Juul S, Knudsen UB, Hvas AM. Low risk of venous thromboembolism following early pregnancy loss in pregnancies conceived by IVF. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2018 Oct 1:33(10):1968-1972. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey271. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30137318]

Sharif S, Eventov M, Kearon C, Parpia S, Li M, Jiang R, Sneath P, Fuentes CO, Marriott C, de Wit K. Comparison of the age-adjusted and clinical probability-adjusted D-dimer to exclude pulmonary embolism in the ED. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019 May:37(5):845-850. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.07.053. Epub 2018 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 30077494]

Delluc A, Le Mao R, Tromeur C, Chambry N, Rault-Nagel H, Bressollette L, Mottier D, Couturaud F, Lacut K. Incidence of upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis in western France: a community-based study. Haematologica. 2019 Jan:104(1):e29-e31. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.194951. Epub 2018 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 30076179]

Carroll BJ, Piazza G. Hypercoagulable states in arterial and venous thrombosis: When, how, and who to test? Vascular medicine (London, England). 2018 Aug:23(4):388-399. doi: 10.1177/1358863X18755927. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30045685]

Sun ML, Wang XH, Huang J, Wang J, Wang Y. [Comparative study on deep venous thrombosis onset in hospitalized patients with different underlying diseases]. Zhonghua nei ke za zhi. 2018 Jun 1:57(6):429-434. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2018.06.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29925128]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBudnik I, Brill A. Immune Factors in Deep Vein Thrombosis Initiation. Trends in immunology. 2018 Aug:39(8):610-623. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.04.010. Epub 2018 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 29776849]

Ashorobi D, Ameer MA, Fernandez R. Thrombosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860701]

Rodriguez V. Thrombosis Complications in Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Risk Factors, Management, and Prevention: Is There Any Role for Pharmacologic Prophylaxis? Frontiers in pediatrics. 2022:10():828702. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.828702. Epub 2022 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 35359904]

Min SK, Kim YH, Joh JH, Kang JM, Park UJ, Kim HK, Chang JH, Park SJ, Kim JY, Bae JI, Choi SY, Kim CW, Park SI, Yim NY, Jeon YS, Yoon HK, Park KH. Diagnosis and Treatment of Lower Extremity Deep Vein Thrombosis: Korean Practice Guidelines. Vascular specialist international. 2016 Sep:32(3):77-104 [PubMed PMID: 27699156]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLurie F, Passman M, Meisner M, Dalsing M, Masuda E, Welch H, Bush RL, Blebea J, Carpentier PH, De Maeseneer M, Gasparis A, Labropoulos N, Marston WA, Rafetto J, Santiago F, Shortell C, Uhl JF, Urbanek T, van Rij A, Eklof B, Gloviczki P, Kistner R, Lawrence P, Moneta G, Padberg F, Perrin M, Wakefield T. The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards. Journal of vascular surgery. Venous and lymphatic disorders. 2020 May:8(3):342-352. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.12.075. Epub 2020 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 32113854]

Bawa H, Weick JW, Dirschl DR, Luu HH. Trends in Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis and Deep Vein Thrombosis Rates After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018 Oct 1:26(19):698-705. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00235. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30153117]

Denny N, Musale S, Edlin H, Serracino-Inglott F, Thachil J. Chronic deep vein thrombosis. Acute medicine. 2018:17(3):144-147 [PubMed PMID: 30129947]

Rahaghi FN, Minhas JK, Heresi GA. Diagnosis of Deep Venous Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism: New Imaging Tools and Modalities. Clinics in chest medicine. 2018 Sep:39(3):493-504. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2018.04.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30122174]

Schick MA, Pacifico L. Deep Venous Thrombosis of the Lower Extremity. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262179]

Lewis TC, Cortes J, Altshuler D, Papadopoulos J. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis: A Narrative Review With a Focus on the High-Risk Critically Ill Patient. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2019 Nov-Dec:34(11-12):877-888. doi: 10.1177/0885066618796486. Epub 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30165770]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOh DK, Song JM, Park DW, Oh SY, Ryu JS, Lee J, Lee SD, Lee JS. The effect of a multidisciplinary team on the implementation rates of major diagnostic and therapeutic procedures of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2019 Jan:48(1):28-33. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.07.008. Epub 2018 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 30115494]

Ten Cate V, Prins MH. Secondary prophylaxis decision-making in venous thromboembolism: interviews on clinical practice in thirteen countries. Research and practice in thrombosis and haemostasis. 2017 Jul:1(1):41-48. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12014. Epub 2017 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 30046672]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoung AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J, Chapman O, Lokare A, Hill C, Hale D, Dunn JA, Lyman GH, Hutchinson C, MacCallum P, Kakkar A, Hobbs FDR, Petrou S, Dale J, Poole CJ, Maraveyas A, Levine M. Comparison of an Oral Factor Xa Inhibitor With Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Patients With Cancer With Venous Thromboembolism: Results of a Randomized Trial (SELECT-D). Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Jul 10:36(20):2017-2023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8034. Epub 2018 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 29746227]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoon GJAM, Van Dam LF, Klok FA, Huisman MV. Management and treatment of deep vein thrombosis in special populations. Expert review of hematology. 2018 Sep:11(9):685-695. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2018.1502082. Epub 2018 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 30016119]

Ha NB, Regal RE. Anticoagulation in Patients With Cirrhosis: Caught Between a Rock-Liver and a Hard Place. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2016 May:50(5):402-9. doi: 10.1177/1060028016631760. Epub 2016 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 26861989]

Kruger PC, Eikelboom JW, Douketis JD, Hankey GJ. Deep vein thrombosis: update on diagnosis and management. The Medical journal of Australia. 2019 Jun:210(11):516-524. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50201. Epub 2019 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 31155730]

Padda IS, Chowdhury YS. Edoxaban. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33351434]

Key NS, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Bohlke K, Lee AYY, Arcelus JI, Wong SL, Balaban EP, Flowers CR, Francis CW, Gates LE, Kakkar AK, Levine MN, Liebman HA, Tempero MA, Lyman GH, Falanga A. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Feb 10:38(5):496-520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01461. Epub 2019 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 31381464]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLi YK, Guo CG, Cheung KS, Liu KSH, Leung WK. Risk of Postcolonoscopy Thromboembolic Events: A Real-World Cohort Study. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2023 Nov:21(12):3051-3059.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.021. Epub 2022 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 36167228]

Cheung KS, Leung WK. Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on novel oral anticoagulants: Risk, prevention and management. World journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Mar 21:23(11):1954-1963. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.1954. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28373761]

Nepal G, Kharel S, Bhagat R, Ka Shing Y, Ariel Coghlan M, Poudyal P, Ojha R, Sunder Shrestha G. Safety and efficacy of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in cerebral venous thrombosis: A meta-analysis. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 2022 Jan:145(1):10-23. doi: 10.1111/ane.13506. Epub 2021 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 34287841]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCohen AT, Hamilton M, Mitchell SA, Phatak H, Liu X, Bird A, Tushabe D, Batson S. Comparison of the Novel Oral Anticoagulants Apixaban, Dabigatran, Edoxaban, and Rivaroxaban in the Initial and Long-Term Treatment and Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2015:10(12):e0144856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144856. Epub 2015 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 26716830]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCohen AT, Hamilton M, Bird A, Mitchell SA, Li S, Horblyuk R, Batson S. Comparison of the Non-VKA Oral Anticoagulants Apixaban, Dabigatran, and Rivaroxaban in the Extended Treatment and Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2016:11(8):e0160064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160064. Epub 2016 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 27487187]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRollins BM, Silva MA, Donovan JL, Kanaan AO. Evaluation of oral anticoagulants for the extended treatment of venous thromboembolism using a mixed-treatment comparison, meta-analytic approach. Clinical therapeutics. 2014 Oct 1:36(10):1454-64.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.06.033. Epub 2014 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 25092394]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAlmutairi AR, Zhou L, Gellad WF, Lee JK, Slack MK, Martin JR, Lo-Ciganic WH. Effectiveness and Safety of Non-vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants for Atrial Fibrillation and Venous Thromboembolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. Clinical therapeutics. 2017 Jul:39(7):1456-1478.e36. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.05.358. Epub 2017 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 28668628]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRoot CW, Dudzinski DM, Zakhary B, Friedman OA, Sista AK, Horowitz JM. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of pulmonary embolism patients: the pulmonary embolism response team (PERT). Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2018:11():187-195. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S151196. Epub 2018 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 29670358]

McCaughan GJB, Favaloro EJ, Pasalic L, Curnow J. Anticoagulation at the extremes of body weight: choices and dosing. Expert review of hematology. 2018 Oct:11(10):817-828. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2018.1517040. Epub 2018 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 30148651]

Fallaha MA, Radha S, Patel S. Safety and efficacy of a new thromboprophylaxis regiment for total knee and total hip replacement: a retrospective cohort study in 265 patients. Patient safety in surgery. 2018:12():22. doi: 10.1186/s13037-018-0169-x. Epub 2018 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 30123323]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence