Introduction

Central venous pressure, which is a measure of pressure in the vena cava, can be used as an estimation of preload and right atrial pressure. Central venous pressure is often used as an assessment of hemodynamic status, particularly in the intensive care unit. The central venous pressure can be measured using a central venous catheter advanced via the internal jugular vein and placed in the superior vena cava near the right atrium. A normal central venous pressure reading is between 8 to 12 mmHg. This value is altered by volume status and/or venous compliance.[1][2][3]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

New evidence suggests no absolute direct correlation between central venous pressure (CVP) and the total blood volume present in the circulation. With the emergence of the concept of fluid responsiveness and its impact on patient outcome, CVP was found to be a poor predictor of fluid responsiveness. Accurate measurements of the central venous pressure were also challenged. A survey revealed that approximately 75% of the respondents made an error in their measurement of CVP. It also showed that many younger clinicians still use central venous pressure for the management of cardiovascular cases despite the doubted accuracy of CVP; this emphasizes the need for proper education regarding central venous pressure [4][5][6]

A systematic review from 2008 has indicated insufficient data to support that central venous pressure should be monitored in intensive care units, operating rooms, and emergency departments. The review also suggested that central venous pressure should only be used as a measure of right ventricular function but not as a measure of volume status in certain patient populations i.e., heart transplant patients, patients with right ventricular infarct, or acute pulmonary embolism. Of note, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign no longer targets a central venous pressure of 8 to 12 mmHg as a gauge of fluid resuscitation. Due to the limitation of the central venous pressure as a static measure, the critical care society realized that parameters such as lactate clearance would more dynamically and accurately attest to the adequacy of end-organ perfusion.

Organ Systems Involved

Several organ systems regulate central venous pressure. The central venous pressure, which is a direct approximation of the right atrial pressure, is dependent on total blood volume and compliance of the central venous compartment. It is also influenced by a myriad of factors, including cardiac output, orthostasis (changing from a standing position to supine), arterial dilation, and preload (which may be increased by abdominal muscle or limb contraction as well as renal failure resulting in fluid retention).

Mechanism

Early experimental studies explored various hemodynamic parameters, including central venous pressure (CVP), venous return (VR), and cardiac output (CO) - their relationship is described by Starling's flow equation Q = delta P/R, where Q represents flow, ΔP represents the pressure gradient, and R represents resistance. Guyton's law further explores this relationship with regard to cardiac performance.[7]

In vivo, the CVP is a functional measure of right atrial and juxta-cardiac pressures (derived from pericardial and thoracic compartments) [7]

Theoretically, when the mean systemic filling pressure equals the central venous pressure, there will be no venous return. The CVP is inversely related to venous return. However, another factor to consider is intrathoracic pressure. If the central venous pressure were to fall below the intrathoracic pressure, the central veins become compressed and limit venous return. The peripheral venous pressure can be affected by a change in volume, and because of their compliant nature, a change in total volume would have a greater effect on the amount of blood present in the veins. The venous tone is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system as well as external compression forces. Under normal physiologic conditions, the right and left ventricular output are equal.

The central venous pressure influences cardiac (left ventricle) output - this is driven by changes in central venous pressure which lead to changes in the filling pressures of the left heart.

Related Testing

The central venous pressure is measured by a central venous catheter placed through either the subclavian or internal jugular veins. The central venous pressure can be monitored using a pressure transducer or amplifier. First, the transducer or amplifier must be zeroed to atmospheric pressure. Then, the transducer must be aligned to the horizontal plane of the tricuspid valve. The central venous pressure can also be measured using an ultrasound machine. The ultrasound can assess fluid responsiveness by measuring the maximal inferior vena cava diameter, inferior vena cava inspiratory collapse, and internal jugular aspect ratio. Amongst these three, the measurement of the maximal inferior vena cava diameter was found to be the best estimate of the central venous pressure, with an inferior vena cava diameter greater than 2 centimeters suggesting elevated central venous pressure and measurement less than 2 centimeters, suggesting low central venous pressure.

Pathophysiology

Low Central Venous Pressure

Some factors that can decrease central venous pressure are hypovolemia or venodilation. Either of these would decrease venous return and thus decrease the central venous pressure. A decrease in central venous pressure is noted when there is more than 10% of blood loss or shift of blood volume. A decrease in intrathoracic pressure caused by forced inspiration causes the vena cavae to collapse which decreases the venous return and, in turn, decreases the central venous pressure.

Elevated Central Venous Pressure

Elevated Central Venous Pressure can occur in heart failure due to decreased contractility, valve abnormalities, and dysrhythmias. Any patients on ventilator assistance that have excessive positive end-expiratory pressure would have an increase in pulmonary arterial resistance which causes an increase in central venous pressure. However, an increased central venous pressure caused by increased pulmonary arterial resistance can also be affected by a decrease in the fraction of inspired oxygen, an increase in ventilation/perfusion abnormalities in the lung, an increase in pericardial pressure, or an increase in intra-abdominal pressure which would increase thoracic pressure. Increased juxta-cardiac pressure - tension pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade, right ventricular infarct, right ventricular outflow obstruction - can also decrease venous return.[7]

Clinical Significance

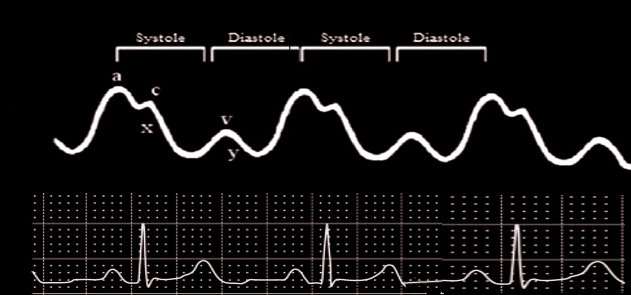

The clinical utility of the central venous pressure can be seen in the assessment of cardiocirculatory status. Elevated CVP will present clinically as a pulsation of the internal jugular vein when a patient is inclined at 45 degrees; however, it can be noted in an upright patient in severe cases.

Elevated CVP is indicative of myocardial contractile dysfunction and/or fluid retention. On the other hand, low central venous pressure is indicative of volume depletion or decreased venous tone. The central venous pressure, despite its numerous limitations, is consistently used universally to guide fluid resuscitation.

The ease of determination of the central venous pressure makes it a clinically attractive, albeit non-specific, indicator of fluid status. As such, other indices, such as the inferior vena cava collapsibility index (IVC CI), must be used adjunctively for a more accurate assessment of volume status [8]

In addition, CVP has been found to be inversely correlated with the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients (with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 55%) thus, TAPSE may be used as a surrogate marker of CVP [9].

Media

References

Russell PS, Hong J, Windsor JA, Itkin M, Phillips ARJ. Renal Lymphatics: Anatomy, Physiology, and Clinical Implications. Frontiers in physiology. 2019:10():251. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00251. Epub 2019 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 30923503]

Hariri G, Joffre J, Leblanc G, Bonsey M, Lavillegrand JR, Urbina T, Guidet B, Maury E, Bakker J, Ait-Oufella H. Narrative review: clinical assessment of peripheral tissue perfusion in septic shock. Annals of intensive care. 2019 Mar 13:9(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0511-1. Epub 2019 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 30868286]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMartin GS, Bassett P. Crystalloids vs. colloids for fluid resuscitation in the Intensive Care Unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of critical care. 2019 Apr:50():144-154. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.031. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30540968]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSenthelal S, Maingi M. Physiology, Jugular Venous Pulsation. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30480931]

Wolfe HA, Mack EH. Making care better in the pediatric intensive care unit. Translational pediatrics. 2018 Oct:7(4):267-274. doi: 10.21037/tp.2018.09.10. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30460178]

Campos Munoz A, Vohra S, Gupta M. Orthostasis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422533]

Berlin DA, Bakker J. Starling curves and central venous pressure. Critical care (London, England). 2015 Feb 16:19(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0776-1. Epub 2015 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 25880040]

Govender J, Postma I, Wood D, Sibanda W. Is there an association between central venous pressure measurement and ultrasound assessment of the inferior vena cava? African journal of emergency medicine : Revue africaine de la medecine d'urgence. 2018 Sep:8(3):106-109. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2018.03.004. Epub 2018 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 30456158]

Zhang H, Wang X, Chen X, Zhang Q, Liu D. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and central venous pressure in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. Cardiovascular ultrasound. 2018 Aug 7:16(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12947-018-0130-2. Epub 2018 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 30081914]