Introduction

Renal involvement in lymphoma is commonly in the presence of widespread nodal or extranodal lymphoma. This is classified as secondary renal lymphoma (SRL). Rarely, lymphoma may involve the kidneys alone without evidence of disease elsewhere; this presentation is termed primary renal lymphoma (PRL). Although the diagnosis of renal lymphoma can be challenging, an awareness of the spectrum of imaging findings can help to differentiate lymphoma from other renal malignancies, such as renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and can lead to appropriate recommendations for biopsy. An accurate diagnosis is critical because renal lymphoma is treated by chemotherapy whereas RCC is typically managed by surgery or ablation.[1][2][3]Renal lymphoma is commonly secondary to lymphomatous infiltration of the kidneys in systemic disseminated lymphoma and advanced stage IV disease while renal lymphoma arising primarily in the renal parenchyma is a rarely described entity. Primary renal lymphoma comprises only 0.7% of extranodal lymphomas.[4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Renal involvement in autopsy cases is secondary to non-Hodgkin disease in 30% to 60% of cases. Immunocompromised patients with uncontrolled Epstein-Barr virus proliferation, organ transplantation, patients undergoing chemotherapeutic therapy, patients with HIV infection, or ataxia-telangiectasia patients are at increased risk. Primary renal lymphoma is of Hodgkin-type arising in hilar nodes or renal parenchyma form only less than 1 % of renal lymphoma. Association of the tumor has been found with chronic inflammatory and infectious diseases like Sjogren, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic pyelonephritis, and Epstein-Barr virus infections.[6][7]

Epidemiology

While renal lymphoma has autopsy incidence of 30% to 60% in lymphoma patients, actual CT diagnosis incidence is approximately 5%. The kidneys are the most common abdominal organ affected by non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Involvement of the kidneys in primary renal lymphoma is rare (less than 1%). It is mostly seen in middle to advanced age. It forms about 0.7% of the extranodal lymphomas in North America. The bilateral presentation is seen in 10% to 20% of the cases.

Pathophysiology

The kidneys are the most common abdominal organ affected by systemic lymphoma according to several studies. Renal involvement is most common with B-cell lymphoma, and the majority are intermediate or high-grade lymphomas including Burkitt and histiocytic varieties. Gross macroscopy reveals fleshy or firm yellow, tan, or gray tumors that are 1 to 20 cm. The pathogenesis of primary renal lymphoma is dubious as the normal kidney does not have any lymphoid tissue. Puente Duanay hypothesized that pre-existing inflammatory processes recruit lymphoid cells into renal parenchyma and an untimely oncogenic event takes place to complete the multistep process of oncogenesis. The renal capsule is rich in lymphatics, and it has been suggested that the tumor penetrates the parenchyma from the capsule, subcapsular tissue, or the renal sinus with subsequent invasion of the renal parenchyma. Tumor proliferation initiates in the interstitium and the adjacent nephrons and collecting ducts, and blood vessels act as a framework for tumor growth. An infiltrative growth pattern results in preservation of the parenchymal structures and renal contour. Consequently, detection of renal involvement becomes difficult and can easily be missed on histopathology. As lymphomatous tumors enlarge, the surrounding renal parenchyma is compressed and displaced causing the formation of solitary or more commonly multiple nodular masses. Uneven infiltrative growth can result in extension beyond the renal capsule into the perinephric space, mimicking primary renal neoplasms. Continued growth may ultimately cause replacement of the whole renal parenchymal architecture.

History and Physical

Renal lymphoma is commonly seen as a part of the spectrum of multi-systemic; however, it may seldom be seen as a primary disease. It usually presents in middle-aged persons although half of the cases may be clinically silent. Presenting symptoms include flank pain, weight loss, fever, night sweats, palpable abdominal mass, hematuria, and deranged renal function usually seen as elevated serum creatinine.

Primary renal lymphoma is an infiltrative tumor that grows without disruption of structure or function. However, the most common presentation of primary renal lymphoma is acute renal failure, flank pain, and mass. The cause for renal failure is somewhat ambiguous, but several theories have been postulated including lymphomatous infiltration of the parenchyma, hypercalcemia due to vitamin D overproduction by the lymphomatous mass or ureteral, and vascular or tubular compression by the lesion.

Evaluation

Renal Function Studies

Laboratory studies to assess renal function include blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine. Although clinical evidence of renal involvement with lymphoma is only seen in 2% to 14 %of patients, an elevated serum creatinine is reported in 26% to 56%. An elevated BUN or creatinine level may indicate bilateral ureteral obstruction subsequent to massive retroperitoneal lymph nodes or as a adverse effect of nephrotoxic chemotherapeutic agents.[8][9][10]

Renal Biopsy

The diagnosis of primary renal lymphoma requires biopsy in most cases as imaging findings are nonspecific. Although fine-needle aspiration is a useful technique, core tissue biopsy with flow cytometry and immunohistochemical staining is recommended as it has a higher diagnostic accuracy according to several studies.

With regard to secondary renal lymphoma (SRL), renal biopsy is usually not required in the presence of disseminated disease. However, it is reported that patients with lymphoma have a higher incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) than the general population. Differentiating SRL presenting as a solitary mass (typically hypovascular) from clear cell RCC (mostly hypervascular) on imaging may be straightforward. Nonetheless, other histologic subtypes of RCC, like papillary and chromophobe RCCs, can also appear hypovascular on imaging, making it harder to differentiate from SRL. In such cases, a renal biopsy may be validated.

Imaging

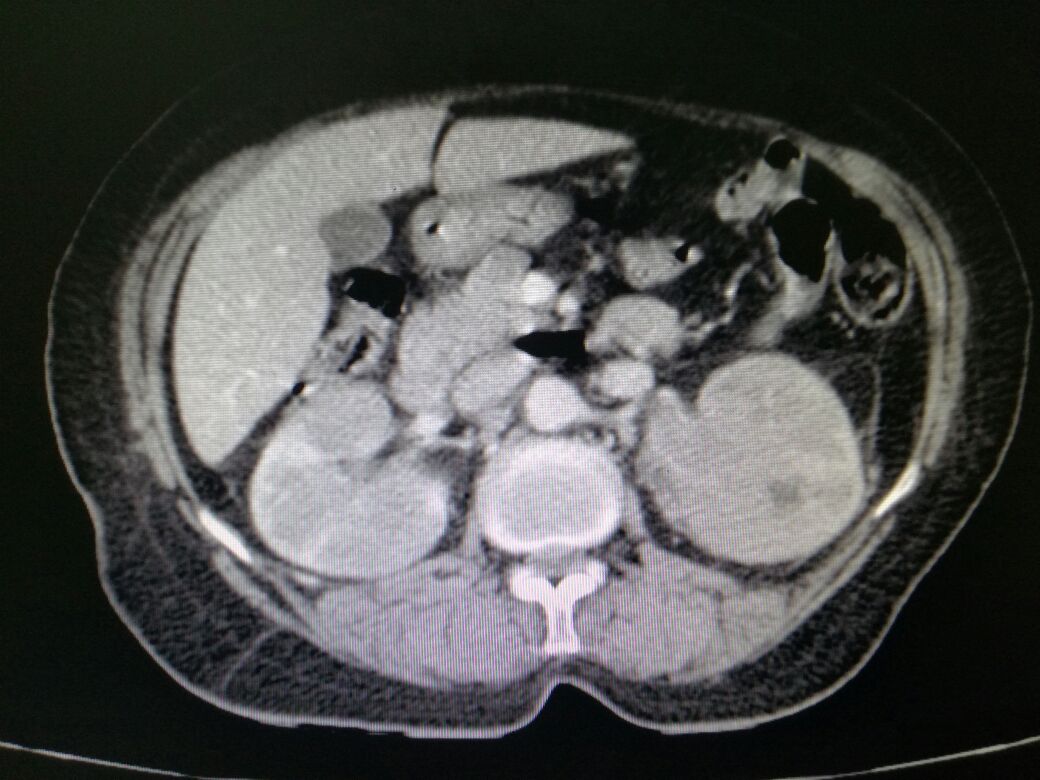

There are several patterns of lymphomatous involvement of kidneys; the most common on imaging is multiple parenchymal nodular masses of variable size, typically 1 to 4.5 cm in diameter. This presentation is seen in approximately 50 to 60% of cases. The lesions are usually bilateral, but unilateral renal presentation can also be seen. The second most common pattern of involvement constitutes a contiguous extension to the kidneys or perinephric space from large retroperitoneal nodal masses (seen in 25% to 30% of cases).

Renal lymphoma presenting as a solitary mass is encountered in 10% to 25% of patients. On non-enhanced CT scan lymphomatous mass is slightly more hyperattenuating than the surrounding normal renal parenchyma. At contrast-enhanced CT, the mass is hypovascular and characteristically demonstrates minimal enhancement. This feature is invaluable in differentiating renal lymphoma from RCC, which mostly manifests moderate to avid enhancement in the arterial phase. Isolated perinephric lymphoma is rarely seen (less than 10% of cases). Contrast-enhanced CT scans are important for demonstrating a ring of homogeneous perinephric tissue which encases the normal parenchyma, with contrast-enhanced causing any significant renal dysfunction. Diffuse renal enlargement without distortion of the reniform shape of the kidneys or formation of any discrete masses presents in 6% to 19% of cases. Nephromegaly is almost always bilateral. If both kidneys are extensively infiltrated, acute renal failure. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates heterogeneous enhancement of the kidneys, loss of the normal corticomedullary differential enhancement, encasement and deformation of the pevicalyceal system, and infiltration of the renal sinus fat. Alternatively, the renal parenchyma is replaced by poorly defined low-attenuation lesions. The collecting system is encased and stretched instead of being displaced. The sonographic picture of infiltrative renal lymphoma is globular enlargement of the kidneys with heterogeneous echotexture and effacement of renal sinus.

Nuclear Imaging

Gallium-67 citrate has been used for diagnosing and staging lymphoma. This radioisotope concentrates in lymphoma. and is taken up by lymphomatous tissue in the kidneys. It also is concentrated in the inflammatory masses of the kidney. The degree of sensitivity increases in case of high grade lymphoma.18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scanning has been commonly used for staging and follow-up after treatment. The use of another agent, technetium-99m (Tc)-labeled antibody (LL2), has been advocated in imaging and staging lymphomas, especially in cases of low-grade lymphoma.

Treatment / Management

Differentiating renal lymphoma from other renal masses is crucial as well as challenging, especially in cases of unilateral lesions that mimic renal carcinomas both radiologically as well as pathologically. The standard management of a renal mass is radial or partial nephrectomy. However, a patient with renal lymphoma is treated with systemic chemotherapy.

Surgery or systemic chemotherapy, with or without radiotherapy, is a widely-used treatment for primary renal lymphoma. The prognosis of patients affected by primary renal lymphoma is grave, despite the absence of disseminated disease. For bilateral renal lymphoma, systemic chemotherapy using a CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen is the treatment of choice; this preserves the organ function, but the subsequent prognosis is poor because although chemotherapy usually improves the renal function. The few cases reported in the literature show increased mortality because of rapid relapse or infections occurring from neutropenia. Alternatively, bilateral nephrectomy invariably leads to the permanent need for hemodialysis. Overall survival rate and long-term disease-free interval are relatively better when surgery and chemotherapy are combined.

Differential Diagnosis

- Abscess

- Acute pyelonephritis

- Angiomyolipoma

- Bladder cancer

- Chronic pyelonephritis

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Renal adenoma

- Renal cyst

- Renal infarction

- Wilms disease

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lymphoma of the kidney may be primary or secondary, but in both cases making a diagnosis is not easy. The disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the pathologist, radiologist, urologist, oncologist, radiation specialist and a team of specialty nurses. To differentiate lymphoma from other renal cancers usually requires a biopsy. Once diagnosed, the treatment is chemotherapy plus radiation. The prognosis of these patients depend on whether the lymphoma is primary or secondary. With advances in treatment, most patients have improved survival but complications of therapy often can be life-threatening.[11][12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Li W, Sun Z. Mechanism of Action for HDAC Inhibitors-Insights from Omics Approaches. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Apr 1:20(7):. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071616. Epub 2019 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 30939743]

Stanescu AL, Acharya PT, Lee EY, Phillips GS. Pediatric Renal Neoplasms:: MR Imaging-Based Practical Diagnostic Approach. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 2019 May:27(2):279-290. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2019.01.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30910098]

Blas L, Roberti J, Petroni J, Reniero L, Cicora F. Renal Medullary Carcinoma: a Report of the Current Literature. Current urology reports. 2019 Jan 17:20(1):4. doi: 10.1007/s11934-019-0865-9. Epub 2019 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 30656488]

Gupta R, Amanam I, Rahmanuddin S, Mambetsariev I, Wang Y, Huang C, Reckamp K, Vora L, Salgia R. Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK)-positive Tumors: Clinical, Radiographic and Molecular Profiles, and Uncommon Sites of Metastases in Patients With Lung Adenocarcinoma. American journal of clinical oncology. 2019 Apr:42(4):337-344. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000508. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30741758]

Velvet AJJ, Bhutani S, Papachristos S, Dwivedi R, Picton M, Augustine T, Morton M. A single-center experience of post-transplant lymphomas involving the central nervous system with a review of current literature. Oncotarget. 2019 Jan 11:10(4):437-448. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26522. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30728897]

Sakr HI, Buckley K, Baiocchi R, Zhao WJ, Hemminger JA. Erdheim Chester disease in a patient with Burkitt lymphoma: a case report and review of literature. Diagnostic pathology. 2018 Nov 24:13(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13000-018-0772-2. Epub 2018 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 30474563]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTsuchimoto A, Masutani K, Omoto K, Okumi M, Okabe Y, Nishiki T, Ota M, Nakano T, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T, Nakamura M, Ishida H, Tanabe K, Japan Academic Consortium of Kidney Transplantation (JACK) Investigators. Kidney transplantation for treatment of end-stage kidney disease after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: case series and literature review. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2019 Apr:23(4):561-568. doi: 10.1007/s10157-018-1672-1. Epub 2018 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 30584654]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOda Y, Ishioka K, Ohtake T, Sato S, Tamai Y, Oki R, Matsui K, Mochida Y, Moriya H, Hidaka S, Kobayashi S. Intravascular lymphoma forming massive aortic tumors complicated with sarcoidosis and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a case report and literature review. BMC nephrology. 2018 Oct 29:19(1):300. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-1106-z. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30373554]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUppal NN, Monga D, Vernace MA, Mehtabdin K, Shah HH, Bijol V, Jhaveri KD. Kidney diseases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2019 Oct 1:34(10):1644-1652. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy320. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30380110]

Ouyang ZZ, Peng TS, Cao QH, Ouyang Y, Li JX, Wei QX, Zhan H. T-cell lymphoma with rhabdomyolysis: case report and literature review. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas. 2018:51(11):e6278. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20176278. Epub 2018 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 30304093]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBenoni H, Eloranta S, Ekbom A, Wilczek H, Smedby KE. Survival among solid organ transplant recipients diagnosed with cancer compared to nontransplanted cancer patients-A nationwide study. International journal of cancer. 2020 Feb 1:146(3):682-691. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32299. Epub 2019 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 30919451]

Mrdenovic S, Zhang Y, Wang R, Yin L, Chu GC, Yin L, Lewis M, Heffer M, Zhau HE, Chung LWK. Targeting Burkitt lymphoma with a tumor cell-specific heptamethine carbocyanine-cisplatin conjugate. Cancer. 2019 Jul 1:125(13):2222-2232. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32033. Epub 2019 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 30840322]