Introduction

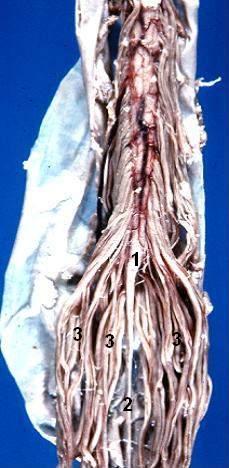

In 1595, French anatomist Andre du Laurens first described the structure of a rope-like tail of fibers at the caudal end of the spinal cord. This bundle of numerous axons was termed the cauda equina, from the Latin translation meaning “horse’s tail,” and it contains nerves which innervate both sensory and motor targets within lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal spinal cord levels. Epidemiologic assessments regard lesions to the cauda equina as uncommon, with a prevalence of 1 to 3 per 100,000 subjects. Typically caused by a herniated intervertebral disc at the L5-S1 levels, such lesions affect females as often as males and manifest as a number of urogenital and neuromuscular symptoms in the namesake “cauda equina syndrome."[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

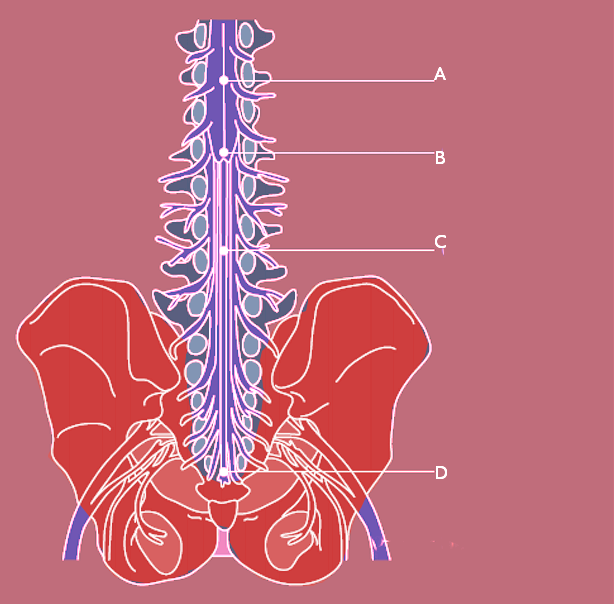

The human spinal cord terminates at the L1-L2 vertebral level in a conical structure called the conus medullaris, which lies just caudad to the anatomical landmark of the 12th rib. The cauda equina contains a bundle of nerves which project distally within the enclosed cavity of the lumbar cistern from the spinal cord and conus medullaris toward the coccyx. Each nerve exits at its respective vertebral level toward targets which are supplied by the L2-S5 spinal cord level. Nerves contained within the cauda equina provide somatic efferent innervation to muscles of the lower extremity and somatic afferent sensations such as vibration, proprioception, pain, and temperature. Parasympathetic nerves provide visceral efferent signals to the urinary bladder from the S2 to S4 spinal cord levels and are responsible for micturition, accomplished by stimulating the detrusor muscle to contract while simultaneously relaxing the internal urethral sphincter. Sympathetic fibers from T11 through L2 exert urinary bladder filling by relaxing the detrusor muscle and contracting the internal urethral sphincter.[4][5]

Embryology

The cauda equina undergoes a dynamic developmental process inside the embryo. When initially formed, the spinal cord occupies the full space inside the arachnoid and dura mater. With skeletal maturation, the vertebral bodies ossify, and the spine elongates. While the vertebral column elongates with the growth of the embryo, the length of the spinal cord itself progresses at a slower rate and creates the potential space of the lumbar cistern. Due to this elongation, lumbar and sacral spinal nerve roots must travel a greater distance inferiorly within the vertebral column to maintain innervation of distal targets. Akin to the rest of the spinal cord, the horsehair projections that together are termed the cauda equina are enveloped in the dura, arachnoid, and pia mater, the 3 meningeal layers.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The cauda equina is supplied by arteries of the same name, which are small and may not be visualized radiographically. Each spinal nerve root has a corresponding medullary artery. A vasocorona surrounding the conus medullaris and the high degree of arterial anastomoses among the nerve roots predispose the vasculature patterns to significant diversity. Lymphatic capillaries occur nearly everywhere in the body except for a small number of sites, including the central nervous system (CNS); consequently, immune surveillance occurs within the layers of the meninges in a medium of cerebrospinal fluid. Cerebrospinal fluid bathes the brain, spinal cord, and cauda equina and is thought to serve as a protective layer of lubrication which provides nutrients and removes waste.

Surgical Considerations

Lumbar puncture (LP) is a diagnostic procedure used to evaluate the contents of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for the presence of blood, infection, or to determine the pressure within the central nervous system. LP procedures involve the insertion of a needle between the vertebrae at the L4 level to access the lumbar cistern through the dura and withdraw cerebrospinal fluid. In order from superficial to deep, the needle pierces through the skin, superficial fascia, supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, ligamentum flavum, epidural space, dura, arachnoid, and into the subarachnoid space. Palpation skills and knowledge of the internal and external anatomy are essential; when coupled with ultrasound guidance, the progression and advancement of the needle may be visualized to reduce complications. Due to the mobility of the nerve roots within the fluid-filled lumbar cistern, it is unlikely that an LP can pierce an individual nerve root and iatrogenic cauda equina syndrome presenting after LP is extremely rare.[6][7][8]

However, even a straightforward LP is not without risk. Post-lumbar puncture, a headache is a common clinical phenomenon best explained by the notion that the brain and dura are no longer suspended and supported by the initial volume of cerebrospinal fluid. Due to the loss of cerebrospinal fluid after a successful LP, a traction force is exerted on the brain and meninges. This may be prevented by the use of a 22-gauge blunted needle in the lumbar puncture itself and subsequently positioning the patient supine to decrease mechanical stretch on the meninges.

Clinical Significance

Effaced and compressed against the internal dura by a herniated nucleus pulposus, the cauda equina may be pinched within the lumbar cistern and affect downstream targets. The clinical significance of this medical event, known as cauda equina syndrome (CES), cannot be overstated due to the possible progression to complete paralysis and/or permanent disability. CES is a rare and emergent scenario characterized by variable symptoms that may include anesthesia of the inner thighs, a condition termed saddle anesthesia. Urinary retention and incontinence of the urinary bladder and bowels are also possible findings. There are 2 modes of CES presentation: acute onset, which is associated with a poorer prognosis, and insidious onset, which typically begins as low back pain but progresses to bowel and urinary incontinence.

Findings also may include sciatica, failure to achieve an erection, a diminished or absent patellar, Achilles, or anal reflex, and loss of rectal sphincter tone with perianal hypesthesia. Hyporeflexia is a lower motor neuron sign caused by impingement of the descending cauda equina nerves against the dura. A high index of suspicion should be advised when a patient has a chief complaint of urinary retention with associated back pain or shooting pains in the lower extremity. In one retrospective study of 39 patients with CES, most sensory disturbances such as reported feelings of pins and needles were localized to the L3-L4 and L5-S1 dermatomes.

Nerves of the cauda equina are most often compressed by an intervertebral disc herniation, which typically occurs in a posterior and lateral trajectory due to the thin nature of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Compression may also occur due to tumors, lumbar region synovial cysts, stenosis, or trauma, and imaging studies are likely to indicate the presence of an intraspinal mass. Immediate surgical decompression should be undertaken to prevent permanent sequelae. In a study where 69% of patients had a sudden onset of CES symptoms, there were significant differences in the resolution of sensory and motor deficits in patients treated within 48 hours compared to those treated greater than 48 hours after the onset of symptoms.

Nerves of the cauda equina may also be affected in meningomyelocele, a severe form of spina bifida caused by a folic acid deficiency in the pregnant female. In meningomyelocele, neural tissues including the meninges and nerve roots protrude through a vertebral defect, typically in the lumbosacral region, and is accompanied by neurological deficits below the level of the lesion.[2][9][10]

Other Issues

The workup of a patient with suspected CES consists of obtaining a pertinent history suggestive of trauma, surgery, or anticoagulation therapy. Perianal or saddle numbness, altered sexual function, or altered sensation during micturition with a high residual volume are also suspect. The physical exam may reveal lower extremity weakness or paresthesia, and/or perianal anesthesia with diminished external anal sphincter tone. In distinguishing between a lesion which compresses the conus medullaris itself rather than the cauda equina, the patellar reflex (L4) is informative; this reflex will typically be spared in conus medullaris compression because the tapered end of the spinal cord contains nerve roots S1-S5. Thus, a cauda equina lesion would compromise both the patellar and Achilles reflexes, while a conus medullaris lesion would spare the patellar reflex. There should be a low threshold for MRI of the lumbar spine as an initial step to triage possible CES, as delay in diagnosis or management is an important notion in prolonged morbidity and the medico-legal considerations associated with CES are disproportionately high.[11][12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Giannini C, Spengel KC, Abell Aleff PC, Rivera M, Wald JT. 24-Year-Old Woman with Recent Onset Back Pain. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). 2015 Nov:25(6):786-7. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12324. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26526948]

Nv A, Rajasekaran S, Ks SVA, Kanna RM, Shetty AP. Factors that influence neurological deficit and recovery in lumbar disc prolapse-a narrative review. International orthopaedics. 2019 Apr:43(4):947-955. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4242-y. Epub 2018 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 30474689]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQuaile A. Cauda equina syndrome-the questions. International orthopaedics. 2019 Apr:43(4):957-961. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4208-0. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30374638]

Ridley LJ, Han J, Ridley WE, Xiang H. Cauda equina: Normal anatomy. Journal of medical imaging and radiation oncology. 2018 Oct:62 Suppl 1():123. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.04_12786. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30309156]

Kunam VK, Velayudhan V, Chaudhry ZA, Bobinski M, Smoker WRK, Reede DL. Incomplete Cord Syndromes: Clinical and Imaging Review. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 Jul-Aug:38(4):1201-1222. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170178. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29995620]

Goodman BP. Disorders of the Cauda Equina. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 2018 Apr:24(2, Spinal Cord Disorders):584-602. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000584. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29613901]

Spirig JM, Farshad M. [CME: Lumbar spinal stenosis]. Praxis. 2018 Jan:107(1):7-15. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a002863. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29295677]

Yáñez ML, Miller JJ, Batchelor TT. Diagnosis and treatment of epidural metastases. Cancer. 2017 Apr 1:123(7):1106-1114. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30521. Epub 2016 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 28026861]

Babu JM, Patel SA, Palumbo MA, Daniels AH. Spinal Emergencies in Primary Care Practice. The American journal of medicine. 2019 Mar:132(3):300-306. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.09.022. Epub 2018 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 30291829]

Will JS, Bury DC, Miller JA. Mechanical Low Back Pain. American family physician. 2018 Oct 1:98(7):421-428 [PubMed PMID: 30252425]

Wáng YXJ, Wu AM, Ruiz Santiago F, Nogueira-Barbosa MH. Informed appropriate imaging for low back pain management: A narrative review. Journal of orthopaedic translation. 2018 Oct:15():21-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2018.07.009. Epub 2018 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 30258783]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoeritzauer I, Pronin S, Carson A, Statham P, Demetriades AK, Stone J. The clinical features and outcome of scan-negative and scan-positive cases in suspected cauda equina syndrome: a retrospective study of 276 patients. Journal of neurology. 2018 Dec:265(12):2916-2926. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9078-2. Epub 2018 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 30298195]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence