Central Line–Associated Blood Stream Infections

Central Line–Associated Blood Stream Infections

Introduction

A central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) is defined as the recovery of a pathogen from a blood culture in a patient who had a central line at the time of infection or within 48 hours before the development of infection. Of all the healthcare-associated infections, CLABSIs are associated with a high-cost burden, accounting for approximately $46,000 per case. Most cases are preventable with proper aseptic techniques, surveillance, and management strategies.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Based on the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) data from January 2006 to October 2007, the order of selected pathogens associated with causing CLABSI is as follows. Gram-positive organisms (coagulase-negative staphylococci, 34.1%; enterococci, 16%; and Staphylococcus aureus, 9.9%) are the most common, followed by gram-negatives (Klebsiella, 5.8%; Enterobacter, 3.9%; Pseudomonas, 3.1%; E. coli, 2.7%; Acinetobacter, 2.2%), Candida species (11.8%), and others (10.5%).[3][4]

Tunneled hemodialysis catheters are prone to CRBSIs. Approximately 40%–80% of CRBSIs are caused by gram-positive organisms. Coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus are the most common organisms. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus is frequently seen. Approximately 20% of gram-negative organisms cause 30% of infections and CRBSIs.[5]

Epidemiology

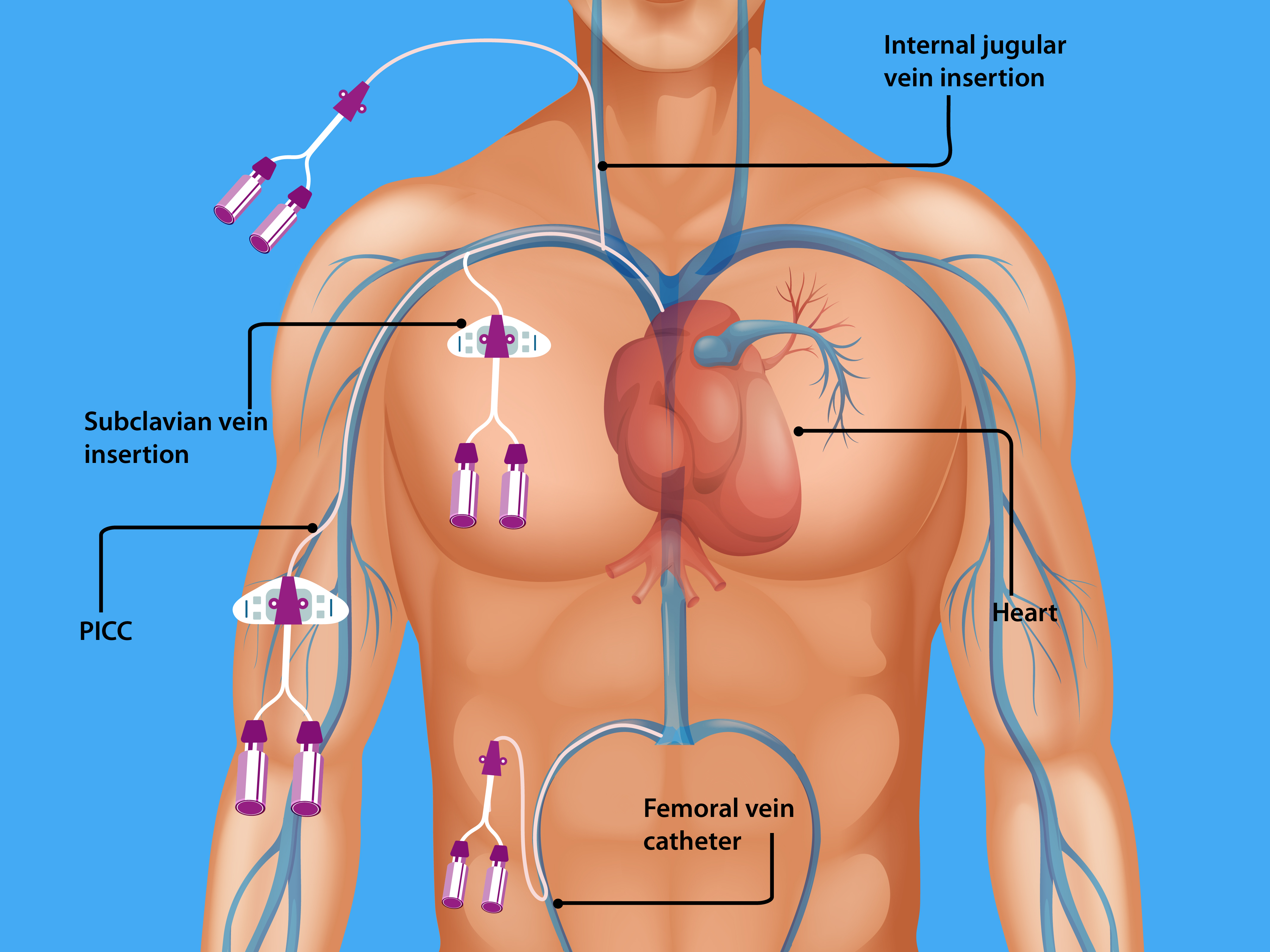

CLABSIs lead to prolonged hospital stays and increase healthcare costs and mortality. An estimated 250,000 bloodstream infections occur annually, and most are related to the presence of intravascular devices. In the United States, the CLABSI rate in intensive care units (ICU) is estimated to be 0.8 per 1000 central line days. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) surveillance data from January 2010 through December 2015 (703 intensive care units in 50 countries) reported a CLABSI rate of 4.1 per 1000 central line days. Many central lines are found outside the ICUs. In 1 study, 55% of ICU and 24% of non-ICU patients had central lines. However, as more patients are located outside the ICU, 70% of hospitalized patients with central venous catheters were outside the ICU.[6] In recent years, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have increased significantly, given some inherent advantages these devices offer.[7] Trained clinical staff can place PICC lines at the bedside with ultrasound guidance, allowing quick central venous access in ICUs and general medical wards. Since PICCs are inserted in a peripheral arm vein with the tip advanced into a central vein (cavoatrial junction or the right atrium) by definition, they are central venous catheters (See Image. Central Venous Catheterization Body Access). The rates of CLABSI associated with PICCs are statistically similar to the conventional central venous catheters (CVCs) in the hospital setting.[8] In a multicenter study of 27,289 patients, CLABSI outcomes were similar between the PICCs placed in the ICU and the general medical ward. However, the study was limited, with an overall low number of events.[9]

Pathophysiology

Central lines are of 2 types: (1) Tunneled catheters are implanted surgically (by creating a subcutaneous track before entering the vein) into the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral vein for long-term (weeks to months) use such as chemotherapy or hemodialysis and (2) Non-tunneled catheters, more commonly used. They are temporary central venous catheters inserted percutaneously and account for most CLABSIs. Within 7 to 10 days of central venous catheter placement, bacteria on the skin surface migrate along the external surface of the catheter from the skin exit site towards the intravascular space. Typically, tunneled catheters have a cuff that causes a fibrotic reaction around the catheter, creating a barrier to bacterial migration). The absence of a tunnel (a subcutaneous tract) places non-tunneled catheters at higher risk for CLABSIs. CLABSIs that occur beyond 10 days are usually caused by contamination of the hub (intraluminal), typically from a health care provider's contaminated hands but rarely from a host and often due to a breach of standard aseptic precautions to access the hub. Less common mechanisms include hematogenous seeding of bacteria from a contaminated infusate or another source.

Chronic illnesses (hemodialysis, malignancy, gastrointestinal tract disorders, pulmonary hypertension), immune-suppressed states (organ transplant, diabetes mellitus), malnutrition, total parenteral nutrition, extremes of age, loss of skin integrity (burns), and prolonged hospitalization before line insertion are host factors that increase the risk of CLABSI.

Femoral central venous catheters are associated with the highest risk of CLABSI, followed by internal jugular and subclavian catheters. Further, the catheter type, insertion conditions (emergent versus elective, use of full barrier precautions versus limited), catheter care, and operator skill also influence the risk of CLABSI.

Pseudomonas is commonly associated with neutropenia, severe illness, or known prior colonization. Candida is associated with risk factors: femoral catheterization, TPN, prolonged administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, hematologic malignancy, or solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Certain bacteria such as staphylococci, Pseudomonas, and Candida produce extracellular polysaccharide [slime (biofilm)], which favors increased virulence, adherence to catheter surface, and resistance to antimicrobial therapy.[10]

History and Physical

Clinical manifestations vary depending on the severity of the illness. Fever and chills are the most common manifestations. Still, they may be masked if the patient is immunocompromised or at extremes of an age where atypical presentations of sepsis occur (altered mental status, hypotension, lethargy, fatigue). Exit site examination to look for signs of inflammation of tunneled catheters with inspection and palpation of the subcutaneous track is essential. Patients may report pain, swelling, or discharge from the exit site and redness surrounding or along the subcutaneous track when exit site or tunnel infections are present. For long-term catheters, difficulty drawing blood or poor flow are risk factors and manifestations of CLABSI.

Evaluation

In addition to the clinical exam, lab investigations are essential for diagnosis and management. Blood culture is the most crucial step towards diagnosis, in addition to completing blood count, serum electrolytes, and renal and liver function tests, which are necessary to assess for severity and co-morbidities. In suspected cases, paired blood cultures (one from the central line and peripheral vein) must be drawn and labeled accordingly before being sent to the lab. In the case of poor peripheral access or when unable to obtain a peripheral sample, 2 or more samples must be drawn from different lumens of a multi-lumen central line. The following definitions help in arriving at a diagnosis:

Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) - Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) definition: Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) is the preferred term used by IDSA. The definite diagnosis of CRBSI requires 1 of the following: Isolation of the same pathogen from a quantitative blood culture drawn through the central line and from a peripheral vein with the single bacterial colony count at least threefold higher in the sample from the central line as compared to that obtained from a peripheral vein (or) same organism recovered from percutaneous blood culture and quantitative (>15 colony-forming units) culture of the catheter tip (or) a shorter time to positive culture (>2 hours earlier) in the central line sample than the peripheral sample (differential time to positivity [ DTP ]).[11]

CLABSI - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition: CLABSI is a surveillance definition used by the CDC and defined as the recovery of a pathogen from a blood culture (a single blood culture for an organism not commonly present on the skin and 2 or more blood cultures for organism commonly present on the skin) in a patient who had a central line at the time of infection or within 48 hours before the development of infection. The infection cannot be related to any other infection the patient might have and must not have been present or incubating when the patient was admitted to the facility.[4]

In the case of tunneled catheters, the accepted definitions for exit site and tunnel infections are as follows:

Exit site infection: Signs of inflammation confined to an area (typically < 2 cm) surrounding the catheter exit site and the presence of exudate that proves to be culture-positive.

Tunnel infection: Inflammation extending beyond 2 cm from the exit site (along with the track or cephalad towards the vein entry site or extending beyond the cuff), typically associated with pain and tenderness along the subcutaneous track and culture-positive exudate at the exit site that may not be seen unless expressed by palpation.

Treatment / Management

When CLABSI is suspected, empiric therapy should be based on the most likely organism, host factors, and the overall clinical picture. While awaiting cultures, empiric treatment should be instituted promptly. In general, coverage for common gram-positive and gram-negative organisms is necessary. The local prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in institutional antibiograms should be considered. The following are some considerations.

- Parenteral vancomycin if methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRSA) is prevalent. Otherwise, parenteral anti-staphylococcal penicillin or cephalosporins such as nafcillin or cefazolin would suffice. If MRSA isolates exhibit a minimum inhibitory concentration of > 2 mg/mL for vancomycin or, in the case of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), daptomycin is the drug of choice.

- The antibiotic choice for gram-negative coverage should be based on the risk of pseudomonal infection and local susceptibility patterns. If the risk of Pseudomonas is low, then a third-generation cephalosporin such as ceftriaxone is appropriate. In patients with a critical illness or high risk for resistant organisms, a combination of a beta-lactam (lactamase inhibitor) and an aminoglycoside is preferred - Cefepime or carbapenem with or without an aminoglycoside. Agents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa are required for neutropenia, severe illness, or known prior colonization.

- Echinocandins (micafungin, caspofungin, anidulafungin) are preferred agents for suspected candidemia if azole resistance is suspected (prior azole use or prevalent nonalbicans candida such as C.glabrata or C.krusei). Otherwise, intravenous fluconazole would suffice. Antifungal therapy must be considered in femoral catheterization, TPN, prolonged administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, hematologic malignancy, or solid organ or bone marrow transplant recipients.

Once antimicrobial susceptibility results are available, de-escalation to specific and appropriate therapy is recommended. If blood cultures have no growth, the need for further empiric antibiotic treatment should be reassessed. Suppose unexplained fever or sepsis persisted in a patient with a short-term central venous or arterial catheter and paired peripheral venipuncture and catheter blood cultures have failed to identify CLABSI. In that case, the catheter should be removed, and the tip should be sent for culture.

All non-tunneled catheters causing CLABSI should be removed promptly, sometimes even before it is proven with the above criteria when clinical suspicion is high. Only for long-term catheters, salvage (systemic therapy coupled with antimicrobial lock [heparin + high concentration of antimicrobial agent that is selected based on susceptibility results]) can be attempted in limited instances such as:

- Uncomplicated CLABSI is caused by organisms other than Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus spp, Micrococcus species, Propionibacteria, fungi, or mycobacteria.

- The patients with limited vascular access sites or the ones who are solely dependent on central access for survival.

In the case of tunneled hemodialysis catheters, uncomplicated exit site infections can be treated with short-course topical or systemic antimicrobials. All tunnel infections require catheter removal due to a high risk of CLABSI. Additional indications for removal of CLABSI from hemodialysis access include:

- Persistent symptoms > 36 hours or severe sepsis, hemodynamic instability(shock), and metastatic infection.

- Blood cultures that remain positive > 72 hours of appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

- Difficulty in clearing organisms (S. aureus, Pseudomonas, or fungi).

- Recurrence of uncomplicated CLABSI (any non-virulent organism) when salvaged for difficult access.

Duration of therapy: For patients with uncomplicated CRBSI (eg, no endocarditis or metastatic infection), in the absence of risk factors for hematogenous spread (eg, hardware, immunosuppression) and negative blood cultures 72 hours of catheter removal, following approach for intravenous antimicrobial therapy is recommended:

- S. aureus - 14 days in the absence of endocarditis

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci - 7 days

- Enterococci and gram-negative bacilli - 10 to 14 days

- Candida - 14 days in the absence of retinitis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for central line-associated bloodstream infections include the following:

- Exit site infections

- Phlebitis

- Pocket infections

- Sepsis

- Tunnel infections

- Urinary tract infection

Pearls and Other Issues

Prevention Guidelines During Insertion

Recent data reveal no difference in the infection rate based on the insertion catheter site. The following are some key components of a prevention program, abstracted from an extensive list provided by the CDC and IDSA.[12][13][10]

- Hand hygiene by washing hands with soap, water, or alcohol-based gels or foams. Gloves do not prevent the need for hand hygiene.

- A strict aseptic technique using maximal sterile barrier precautions, including a full-body drape when inserting central venous catheters.

- Use 2% chlorhexidine skin preparations for disinfecting/ cleaning skin before insertion.

- Ultrasound guidance by an experienced provider for placement to circumvent mechanical complications and reduce the number of attempts.

- Avoid the femoral vein for central line placement, and prefer the subclavian vein when possible for non-tunneled catheters.

- Promptly remove any central line that is no longer required.

- Replace central lines placed during an emergency (asepsis not assured) as soon as possible or within 48 hours.

- Use a checklist.

Prevention Guidelines During Maintenance

- Disinfect the catheter hubs, injection ports, and connections before accessing the line.

- Replace administration sets other than sets used for lipids or blood products every 96 hours.

- Assess the need for the central line daily.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) is a prevalent problem in the intensive care unit. These infections are associated with over 28,000 deaths yearly and cost over $2 billion. Only through best practices, protocols, checklists, and establishing a culture of patient safety in healthcare institutions can CLABSI be reduced to zero.[14] One of the significant reasons for central line removal is an infection or suspicion. This clinical practice leads to prolonged hospital stays and increased procedures and complication rates.

One of the challenges with central lines is the variety of catheter types inserted by diverse staff. In many hospitals, central lines are inserted by specialists, including anesthesiologists, surgeons, emergency room physicians, radiologists, and critical care physicians.[15] PICC lines are often inserted by trained clinical staff. This heterogeneity has resulted in varied outcomes, but infections remain a common problem in almost every study.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Over the years, many guidelines have been established; some hospitals have a policy that for long-term access, the line can only be inserted by a dedicated team that consists of the surgeon, nurses, and a pharmacist who monitors the patient. In addition, when administering TPN, 1 port is dedicated to nutrition. Plus, in some units, only clinicians with training in central lines can infuse medications and other solutions. Evidence-based guidelines show that adhering to protocols can reduce the rate of CLABSI. However, audits of clinicians who insert the central lines and monitor the lines for infections are vital to ensure compliance.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hallam C, Jackson T, Rajgopal A, Russell B. Establishing catheter-related bloodstream infection surveillance to drive improvement. Journal of infection prevention. 2018 Jul:19(4):160-166. doi: 10.1177/1757177418767759. Epub 2018 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 30013620]

Aloush SM, Alsaraireh FA. Nurses' compliance with central line associated blood stream infection prevention guidelines. Saudi medical journal. 2018 Mar:39(3):273-279. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.3.21497. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29543306]

Atilla A, Doğanay Z, Kefeli Çelik H, Demirağ MD, S Kiliç S. Central line-associated blood stream infections: characteristics and risk factors for mortality over a 5.5-year period. Turkish journal of medical sciences. 2017 Apr 18:47(2):646-652. doi: 10.3906/sag-1511-29. Epub 2017 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 28425261]

Wright MO, Decker SG, Allen-Bridson K, Hebden JN, Leaptrot D. Healthcare-associated infections studies project: An American Journal of Infection Control and National Healthcare Safety Network data quality collaboration: Location mapping. American journal of infection control. 2018 May:46(5):577-578. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.12.012. Epub 2018 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 29449023]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFarrington CA, Allon M. Management of the Hemodialysis Patient with Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2019 Apr 5:14(4):611-613. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13171118. Epub 2019 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 30837242]

Ziegler MJ, Pellegrini DC, Safdar N. Attributable mortality of central line associated bloodstream infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection. 2015 Feb:43(1):29-36. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0689-y. Epub 2014 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 25331552]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2013 Sep:24(9):1323-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.04.010. Epub 2013 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 23876551]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChopra V, O'Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2013 Sep:34(9):908-18. doi: 10.1086/671737. Epub 2013 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 23917904]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGovindan S, Snyder A, Flanders SA, Chopra V. Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters in the ICU: A Retrospective Study of Adult Medical Patients in 52 Hospitals. Critical care medicine. 2018 Dec:46(12):e1136-e1144. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003423. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30247241]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBell T, O'Grady NP. Prevention of Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2017 Sep:31(3):551-559. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.05.007. Epub 2017 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 28687213]

Lissauer ME, Leekha S, Preas MA, Thom KA, Johnson SB. Risk factors for central line-associated bloodstream infections in the era of best practice. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2012 May:72(5):1174-80. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824d1085. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22673242]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee KH, Cho NH, Jeong SJ, Kim MN, Han SH, Song YG. Effect of Central Line Bundle Compliance on Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. Yonsei medical journal. 2018 May:59(3):376-382. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.3.376. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29611399]

Norris LB, Kablaoui F, Brilhart MK, Bookstaver PB. Systematic review of antimicrobial lock therapy for prevention of central-line-associated bloodstream infections in adult and pediatric cancer patients. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2017 Sep:50(3):308-317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.06.013. Epub 2017 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 28689878]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSagana R, Hyzy RC. Achieving zero central line-associated bloodstream infection rates in your intensive care unit. Critical care clinics. 2013 Jan:29(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.10.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23182523]

Takashima M, Schults J, Mihala G, Corley A, Ullman A. Complication and Failures of Central Vascular Access Device in Adult Critical Care Settings. Critical care medicine. 2018 Dec:46(12):1998-2009. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003370. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30095499]