Heart Transplantation Allograft Vasculopathy

Heart Transplantation Allograft Vasculopathy

Introduction

There are 5.1 million patients with chronic heart failure in the United States, and heart failure is the leading cause of hospitalization among adults greater than 65 years of age.[1] With more than 1 million patients being hospitalized for the primary diagnosis of heart failure, Medicare spending exceeds $17 billion per annum on this diagnosis.[2] Despite advances in mechanical circulatory support, cardiac transplant remains the definitive treatment intervention for patients with advanced heart failure and refractory symptoms who cannot be managed with optimal medical therapy.

Since the first human heart transplant by Dr. Christiaan Barnard in 1967, a slew of disruptive innovations and multidisciplinary efforts have sophisticated the field.[3] At present, over 5,000 heart transplants are carried out worldwide every year.[4] Despite the encouraging numbers, obstacles still exist.

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) is a recognized long-term complication seen post-cardiac transplant. Considered a chronic fibroproliferative rejection to the transplanted heart, it is amongst the top three causes of death after the first year of transplantation. The prevalence of CAV in patients post-cardiac transplant at 1, 5, and 10 years was 8%, 29%, and 47%, respectively as described by the 2019 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) registry data report.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy is a pan-arterial disease limited to the allograft. Its etiology is multifactorial in origin, with the primary cause being inflammation driven by both cellular and antibody-mediated rejection processes and anti-HLA antibodies against donor tissue. In accordance with the inflammatory burden in this disease process, elevation in serum C-reactive protein is a marker for CAV and allograft failure.[6][7][8] Other contributing factors include hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, hypertension, and Cytomegalovirus infection.[9][10]

Epidemiology

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy is one of the top three causes of death 1-year post-cardiac transplant, accounting for an estimated 1 in 8 deaths in transplant survivors who live beyond one year.[11] The prevalence of CAV in patients post-cardiac transplant at 1, 5, and 10 years was 8%, 29%, and 47%, respectively, as described by the 2019 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) registry data report.[5] Male donors and older age donors were linked to an increased risk of CAV.[12] Younger aged recipients were found to be at a higher risk for CAV.[13][14]

Pathophysiology

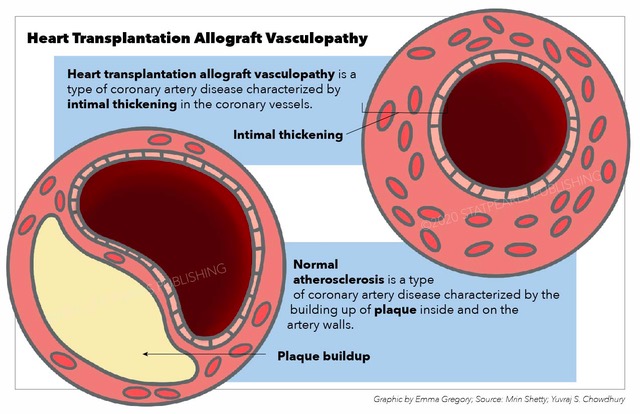

The pathophysiology of CAV is complex, with an interplay of immunological and non-immunological factors. Inflammation may be triggered by donor arrest, organ procurement, and allograft ischemia and reperfusion. CAV is a pan-arterial process characterized by diffuse concentric hyperplasia of the intima seen in epicardial coronary arteries. It also extends to the microvasculature, causing concentric medial disease.[15][16][17] This is in contrast to atherosclerosis, which is non-circumferential, focal, and common in the proximal epicardial vessels. Thrombotic occlusion of the vessel lumen, which is seen in atherosclerosis is an uncommon finding in CAV. However, the two frequently coexist. There is a strong association between platelet activation and CAV.[18] This has been hypothesized as the reason for intramural thrombi formation associated with the disease.[19]

Intravascular ultrasound-guided studies have shown that most of the intimal thickening occurs during the first year post-transplant.[20] An increase in maximal intimal thickness less than 0.5 mm within the first-year post-transplant is associated with an unfavorable prognosis.[21][22]

Histopathology

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy encompasses a constellation of vascular changes characterized by intimal fibromuscular hyperplasia (arteriosclerosis), vasculitis, and atherosclerosis. Veins, in addition to arteries, are affected. Immunohistochemistry demonstrates the infiltration of macrophages and T lymphocytes into the intima, media, and/or adventitia of affected vessels. In contrast to atherosclerosis, calcium deposition is not a prominent finding, even in severely stenotic arteries.[23]

History and Physical

Since the transplanted heart is denervated, the recipient typically does not perceive angina or ischemic pain. Thus, patients with CAV may be asymptomatic or complain of non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, palpitations, abdominal discomfort, and nausea.[24] If the diagnosis is made late, after the onset of heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, the prognosis is usually poor. In rare cases, sudden cardiac death may be the initial presentation of CAV. Consequently, surveillance testing is imperative to monitor recipients closely for early evidence of CAV as clinical manifestations are an unreliable metric.[3]

Evaluation

All post-cardiac transplant patients should undergo routine screening for cardiac allograft vasculopathy, as early detection may improve prognosis.

During the first 5 years post-transplant, coronary angiography should be performed every 1 or 2 years if renal function is preserved (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥30 to 40 mL/min/1.73 m). In cases of significant renal impairment (<30 to 40 mL/min/1.73 m), annual dobutamine stress echocardiography should be performed to assess for inducible coronary ischemia.[25][26] Dobutamine stress echo has been extensively validated as a non-invasive assessment correlating with prognosis in post-cardiac transplant patients.[27][28][29]

Five years post-transplant, low-risk patients can continue surveillance with annual dobutamine stress echocardiography. If patients have evidence of evolving CAV, they should undergo annual coronary angiograms so long as renal function permits. For those patients with poor quality echocardiography images, a dobutamine or dipyridamole stress radionuclide myocardial perfusion study can be performed.[30]

Coronary angiography should be performed on post-transplant patients who present with a change in clinical status and graft dysfunction with a drop in left ventricular ejection fraction, which cannot be explained by acute rejection.

It should be noted that CAV narrows the coronary arteries in a diffuse, concentric pattern, unlike atherosclerosis, which is eccentric and focal and easier to detect on coronary angiography. Thus, angiography has its limitations, especially in early CAV, and may underestimate the severity and burden of the disease. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), in conjunction with coronary flow reserve measurements, overcome this limitation.[31][32][33][34][35] In the future, optical coherence tomography (OCT) may replace or supplement intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) as it allows for high-resolution assessment of the coronary artery wall architecture and composition.[36] Conversely, the absence of coronary angiographic disease was a predictor of survival without adverse cardiac events at two years.[37]

Once the diagnosis of CAV has been established, echocardiograms should be performed to follow left ventricular ejection fraction and allograft dysfunction serially. In addition, annual coronary angiograms aid in the diagnosis of lesions amenable to percutaneous coronary interventions or, in advanced cases, if re-transplantation should be considered.

Treatment / Management

Prevention of Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy

mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus and sirolimus have been shown to prevent or slow the progression of cardiac allograft vasculopathy given their anti-proliferative properties. However, adverse effects, such as renal impairment and impaired wound healing, may limit their use.[38][39][40](A1)

Statin therapy has been shown to reduce the incidence of CAV post-transplant. In addition, these patients have a high incidence of hyperlipidemia, which is also benefitted by statin therapy.[41] Thus, all post-transplant patients should be on statin therapy. Within the statin group, pravastatin and simvastatin have proven to improve survival in these patients.[42][43](A1)

Treatment of CAV

Short-term augmentation of immunosuppressive therapy with mTOR inhibitors may halt progression or cause regression of CAV; however, more data are required to substantiate this.[44] In addition, the risks of increased immunosuppression, including infection and malignancy, may negate these supposed benefits. In a cohort of 163 post-cardiac transplant patients, the anti-CD-20 antibody rituximab was studied as a treatment for CAV. However, IVUS guided imaging showed an increased progression of CAV in patients on Rituximab as compared to placebo.[45]

If the extent of CAV is limited, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty may be used as a palliative option to treat discrete lesions; however, restenosis is a complication. In such cases, there may be a role for directional coronary atherectomy.[46] Coronary artery bypass grafting has been performed in a selected group of cases with good medium-term outcomes. However, there remained a risk of disease progression and future need for percutaneous or surgical intervention. At this time, re-transplantation is the only definitive treatment option for patients with a significant burden of CAV.[47] (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Graft dysfunction may present as acute or chronic heart failure or arrhythmias. In such cases, it is important to distinguish cardiac allograft vasculopathy from rejection reaction (cellular or humoral) and non-specific graft dysfunction. Rejection reactions are diagnosed on endomyocardial biopsy. If CAV is suspected, coronary angiography should be performed if renal function permits. The diffuse luminal narrowing is suggestive of CAV. In contrast, focal eccentric lesions, more commonly in the proximal epicardial vessels is more suggestive of atherosclerosis, though the two may exist in tandem.

- Atherosclerosis

- Non-specific graft dysfunction

- Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder

- Transplant rejection

Prognosis

The presence of cardiac allograft vasculopathy portends a worse prognosis for patients post-cardiac transplant. A reliable surrogate marker for subsequent mortality, non-fatal major adverse cardiac events, and development of angiographically significant CAV through five years post-transplant is the progression of intimal thickening ≥0.5 mm in the first year post-transplant.[21] The prevalence of CAV in patients post-cardiac transplant at 1, 5, and 10 years was 8%, 29%, and 47% respectively, as described by the 2019 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) registry data report.[5][48]

Complications

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy may manifest as graft dysfunction in the form of arrhythmias, acute or chronic heart failure and in the worst cases as sudden cardiac death.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Proper diagnosis and management of cardiac allograft vasculopathy can majorly impact a heart transplant patient's lifespan and can have long-term quality of life effects. Healthcare practitioners should thoroughly counsel patients post-cardiac transplant about the implications of cardiac allograft vasculopathy so that they can make informed decisions about their treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of cardiac allograft vasculopathy in post-cardiac transplant patients requires an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals that includes a nurse, physician assistant, laboratory technologists, pharmacists, pathologists, social workers, and a number of physicians in different specialties. Before the transplant, a social worker must assess the patient's socioeconomic factors to see if compliance with medication and support through the process of transplant is adequate. Nurses, especially advanced practice nurses, and PAs play an essential link between patients and cardiologists. Given the high number of medications prescribed post-transplant, with various interactions and side effects, pharmacists become an integral part of the management team, and emphasis should be placed on patient education. CAV may be confused for graft rejection, in which case endomyocardial biopsies aid in the diagnosis, and for this, a pathologist trained in immunology is vital. Lastly, not only cardiologists and cardiac surgeons but primary care physicians, nephrologists, hemato-oncologists, and pulmonologists may have a role to play in the management of these patients, and interprofessional rounds during inpatient hospitalizations are imperative to improving the quality of care delivered.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Oct 15:128(16):e240-327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. Epub 2013 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 23741058]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern SM, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O'Donnell C, Roger V, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wilson M, Hong Y, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008 Jan 29:117(4):e25-146 [PubMed PMID: 18086926]

Stehlik J, Kobashigawa J, Hunt SA, Reichenspurner H, Kirklin JK. Honoring 50 Years of Clinical Heart Transplantation in Circulation: In-Depth State-of-the-Art Review. Circulation. 2018 Jan 2:137(1):71-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029753. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29279339]

Lund LH, Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb S, Kucheryavaya AY, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Chambers DC, Yusen RD, Stehlik J, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fourth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2017; Focus Theme: Allograft ischemic time. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2017 Oct:36(10):1037-1046. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.07.019. Epub 2017 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 28779893]

Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, Harhay MO, Hayes D Jr, Hsich E, Meiser B, Potena L, Robinson A, Rossano JW, Sadavarte A, Singh TP, Zuckermann A, Stehlik J, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-sixth adult heart transplantation report - 2019; focus theme: Donor and recipient size match. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2019 Oct:38(10):1056-1066. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.08.004. Epub 2019 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 31548031]

Eisenberg MS, Chen HJ, Warshofsky MK, Sciacca RR, Wasserman HS, Schwartz A, Rabbani LE. Elevated levels of plasma C-reactive protein are associated with decreased graft survival in cardiac transplant recipients. Circulation. 2000 Oct 24:102(17):2100-4 [PubMed PMID: 11044427]

Labarrere CA, Lee JB, Nelson DR, Al-Hassani M, Miller SJ, Pitts DE. C-reactive protein, arterial endothelial activation, and development of transplant coronary artery disease: a prospective study. Lancet (London, England). 2002 Nov 9:360(9344):1462-7 [PubMed PMID: 12433514]

Hognestad A, Endresen K, Wergeland R, Stokke O, Geiran O, Holm T, Simonsen S, Kjekshus JK, Andreassen AK. Plasma C-reactive protein as a marker of cardiac allograft vasculopathy in heart transplant recipients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003 Aug 6:42(3):477-82 [PubMed PMID: 12906976]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDelgado JF, Reyne AG, de Dios S, López-Medrano F, Jurado A, Juan RS, Ruiz-Cano MJ, Dolores Folgueira M, Gómez-Sánchez MÁ, Aguado JM, Lumbreras C. Influence of cytomegalovirus infection in the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2015 Aug:34(8):1112-9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.03.015. Epub 2015 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 25940077]

Chang DH, Kobashigawa JA. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 2015 Oct:13(10):1147-54. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1087312. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26401922]

Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Dipchand AI, Goldfarb S, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Yusen RD, Stehlik J. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-second Official Adult Heart Transplantation Report--2015; Focus Theme: Early Graft Failure. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2015 Oct:34(10):1244-54. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.08.003. Epub 2015 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 26454738]

Gao HZ, Hunt SA, Alderman EL, Liang D, Yeung AC, Schroeder JS. Relation of donor age and preexisting coronary artery disease on angiography and intracoronary ultrasound to later development of accelerated allograft coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997 Mar 1:29(3):623-9 [PubMed PMID: 9060902]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJohnson MR. Transplant coronary disease: nonimmunologic risk factors. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 1992 May-Jun:11(3 Pt 2):S124-32 [PubMed PMID: 1622991]

Stoica SC, Cafferty F, Pauriah M, Taylor CJ, Sharples LD, Wallwork J, Large SR, Parameshwar J. The cumulative effect of acute rejection on development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2006 Apr:25(4):420-5 [PubMed PMID: 16563972]

Tuzcu EM, De Franco AC, Goormastic M, Hobbs RE, Rincon G, Bott-Silverman C, McCarthy P, Stewart R, Mayer E, Nissen SE. Dichotomous pattern of coronary atherosclerosis 1 to 9 years after transplantation: insights from systematic intravascular ultrasound imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1996 Mar 15:27(4):839-46 [PubMed PMID: 8613612]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTanaka H, Swanson SJ, Sukhova G, Schoen FJ, Libby P. Early proliferation of medial smooth muscle cells in coronary arteries of rabbit cardiac allografts during immunosuppression with cyclosporine A. Transplantation proceedings. 1995 Jun:27(3):2062-5 [PubMed PMID: 7792886]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHiemann NE, Wellnhofer E, Knosalla C, Lehmkuhl HB, Stein J, Hetzer R, Meyer R. Prognostic impact of microvasculopathy on survival after heart transplantation: evidence from 9713 endomyocardial biopsies. Circulation. 2007 Sep 11:116(11):1274-82 [PubMed PMID: 17709643]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFateh-Moghadam S, Bocksch W, Ruf A, Dickfeld T, Schartl M, Pogátsa-Murray G, Hetzer R, Fleck E, Gawaz M. Changes in surface expression of platelet membrane glycoproteins and progression of heart transplant vasculopathy. Circulation. 2000 Aug 22:102(8):890-7 [PubMed PMID: 10952958]

Arbustini E, Dal Bello B, Morbini P, Gavazzi A, Specchia G, Viganò M. Immunohistochemical characterization of coronary thrombi in allograft vascular disease. Transplantation. 2000 Mar 27:69(6):1095-101 [PubMed PMID: 10762213]

Tsutsui H, Ziada KM, Schoenhagen P, Iyisoy A, Magyar WA, Crowe TD, Klingensmith JD, Vince DG, Rincon G, Hobbs RE, Yamagishi M, Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM. Lumen loss in transplant coronary artery disease is a biphasic process involving early intimal thickening and late constrictive remodeling: results from a 5-year serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2001 Aug 7:104(6):653-7 [PubMed PMID: 11489770]

Kobashigawa JA, Tobis JM, Starling RC, Tuzcu EM, Smith AL, Valantine HA, Yeung AC, Mehra MR, Anzai H, Oeser BT, Abeywickrama KH, Murphy J, Cretin N. Multicenter intravascular ultrasound validation study among heart transplant recipients: outcomes after five years. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005 May 3:45(9):1532-7 [PubMed PMID: 15862430]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChih S, Chong AY, Mielniczuk LM, Bhatt DL, Beanlands RS. Allograft Vasculopathy: The Achilles' Heel of Heart Transplantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Jul 5:68(1):80-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27364054]

Lu WH, Palatnik K, Fishbein GA, Lai C, Levi DS, Perens G, Alejos J, Kobashigawa J, Fishbein MC. Diverse morphologic manifestations of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a pathologic study of 64 allograft hearts. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2011 Sep:30(9):1044-50. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.04.008. Epub 2011 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 21640617]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGao SZ, Schroeder JS, Hunt SA, Billingham ME, Valantine HA, Stinson EB. Acute myocardial infarction in cardiac transplant recipients. The American journal of cardiology. 1989 Nov 15:64(18):1093-7 [PubMed PMID: 2816760]

Mehra MR, Crespo-Leiro MG, Dipchand A, Ensminger SM, Hiemann NE, Kobashigawa JA, Madsen J, Parameshwar J, Starling RC, Uber PA. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation working formulation of a standardized nomenclature for cardiac allograft vasculopathy-2010. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2010 Jul:29(7):717-27. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20620917]

Badano LP, Miglioranza MH, Edvardsen T, Colafranceschi AS, Muraru D, Bacal F, Nieman K, Zoppellaro G, Marcondes Braga FG, Binder T, Habib G, Lancellotti P, Document reviewers. European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging/Cardiovascular Imaging Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology recommendations for the use of cardiac imaging to assess and follow patients after heart transplantation. European heart journal. Cardiovascular Imaging. 2015 Sep:16(9):919-48. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev139. Epub 2015 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 26139361]

Elhendy A, van Domburg RT, Vantrimpont P, Sozzi FB, Bax JJ, Poldermans D, Roelandt JR, Maat LP, Balk AH. Impact of heart transplantation on the safety and feasibility of the dobutamine stress test. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2001 Apr:20(4):399-406 [PubMed PMID: 11295577]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAkosah KO, McDaniel S, Hanrahan JS, Mohanty PK. Dobutamine stress echocardiography early after heart transplantation predicts development of allograft coronary artery disease and outcome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1998 Jun:31(7):1607-14 [PubMed PMID: 9626841]

Spes CH, Klauss V, Mudra H, Schnaack SD, Tammen AR, Rieber J, Siebert U, Henneke KH, Uberfuhr P, Reichart B, Theisen K, Angermann CE. Diagnostic and prognostic value of serial dobutamine stress echocardiography for noninvasive assessment of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a comparison with coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 1999 Aug 3:100(5):509-15 [PubMed PMID: 10430765]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFang JC, Rocco T, Jarcho J, Ganz P, Mudge GH. Noninvasive assessment of transplant-associated arteriosclerosis. American heart journal. 1998 Jun:135(6 Pt 1):980-7 [PubMed PMID: 9630101]

Gao SZ, Alderman EL, Schroeder JS, Hunt SA, Wiederhold V, Stinson EB. Progressive coronary luminal narrowing after cardiac transplantation. Circulation. 1990 Nov:82(5 Suppl):IV269-75 [PubMed PMID: 2225415]

St Goar FG,Pinto FJ,Alderman EL,Fitzgerald PJ,Stinson EB,Billingham ME,Popp RL, Detection of coronary atherosclerosis in young adult hearts using intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 1992 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 1516187]

Tuzcu EM,Kapadia SR,Sachar R,Ziada KM,Crowe TD,Feng J,Magyar WA,Hobbs RE,Starling RC,Young JB,McCarthy P,Nissen SE, Intravascular ultrasound evidence of angiographically silent progression in coronary atherosclerosis predicts long-term morbidity and mortality after cardiac transplantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005 May 3; [PubMed PMID: 15862431]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMehra MR, Ventura HO, Stapleton DD, Smart FW, Collins TC, Ramee SR. Presence of severe intimal thickening by intravascular ultrasonography predicts cardiac events in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 1995 Jul-Aug:14(4):632-9 [PubMed PMID: 7578168]

Wellnhofer E, Stypmann J, Bara CL, Stadlbauer T, Heidt MC, Kreider-Stempfle HU, Sohn HY, Zeh W, Comberg T, Eckert S, Dengler T, Ensminger SM, Hiemann NE. Angiographic assessment of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: results of a Consensus Conference of the Task Force for Thoracic Organ Transplantation of the German Cardiac Society. Transplant international : official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 2010 Nov:23(11):1094-104. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01096.x. Epub 2010 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 20477994]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShan P, Dong L, Maehara A, Nazif TM, Ali ZA, Rabbani LE, Apfelbaum MA, Dalton K, Marboe CC, Mancini DM, Mintz GS, Weisz G. Comparison Between Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy and Native Coronary Atherosclerosis by Optical Coherence Tomography. The American journal of cardiology. 2016 Apr 15:117(8):1361-8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.01.036. Epub 2016 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 26920081]

Barbir M, Lazem F, Banner N, Mitchell A, Yacoub M. The prognostic significance of non-invasive cardiac tests in heart transplant recipients. European heart journal. 1997 Apr:18(4):692-6 [PubMed PMID: 9129903]

Eisen HJ, Tuzcu EM, Dorent R, Kobashigawa J, Mancini D, Valantine-von Kaeppler HA, Starling RC, Sørensen K, Hummel M, Lind JM, Abeywickrama KH, Bernhardt P, RAD B253 Study Group. Everolimus for the prevention of allograft rejection and vasculopathy in cardiac-transplant recipients. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Aug 28:349(9):847-58 [PubMed PMID: 12944570]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEisen HJ, Kobashigawa J, Starling RC, Pauly DF, Kfoury A, Ross H, Wang SS, Cantin B, Van Bakel A, Ewald G, Hirt S, Lehmkuhl H, Keogh A, Rinaldi M, Potena L, Zuckermann A, Dong G, Cornu-Artis C, Lopez P. Everolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil in heart transplantation: a randomized, multicenter trial. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013 May:13(5):1203-16. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12181. Epub 2013 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 23433101]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKeogh A, Richardson M, Ruygrok P, Spratt P, Galbraith A, O'Driscoll G, Macdonald P, Esmore D, Muller D, Faddy S. Sirolimus in de novo heart transplant recipients reduces acute rejection and prevents coronary artery disease at 2 years: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2004 Oct 26:110(17):2694-700 [PubMed PMID: 15262845]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBilchick KC, Henrikson CA, Skojec D, Kasper EK, Blumenthal RS. Treatment of hyperlipidemia in cardiac transplant recipients. American heart journal. 2004 Aug:148(2):200-10 [PubMed PMID: 15308989]

Kobashigawa JA, Katznelson S, Laks H, Johnson JA, Yeatman L, Wang XM, Chia D, Terasaki PI, Sabad A, Cogert GA. Effect of pravastatin on outcomes after cardiac transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 1995 Sep 7:333(10):621-7 [PubMed PMID: 7637722]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWenke K, Meiser B, Thiery J, Nagel D, von Scheidt W, Steinbeck G, Seidel D, Reichart B. Simvastatin reduces graft vessel disease and mortality after heart transplantation: a four-year randomized trial. Circulation. 1997 Sep 2:96(5):1398-402 [PubMed PMID: 9315523]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLamich R, Ballester M, Martí V, Brossa V, Aymat R, Carrió I, Bernà L, Campreciós M, Puig M, Estorch M, Flotats A, Bordes R, Garcia J, Augè, Padró JM, Caralps JM, Narula J. Efficacy of augmented immunosuppressive therapy for early vasculopathy in heart transplantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1998 Aug:32(2):413-9 [PubMed PMID: 9708469]

Starling RC, Armstrong B, Bridges ND, Eisen H, Givertz MM, Kfoury AG, Kobashigawa J, Ikle D, Morrison Y, Pinney S, Stehlik J, Tripathi S, Sayegh MH, Chandraker A, CTOT-11 Study Investigators. Accelerated Allograft Vasculopathy With Rituximab After Cardiac Transplantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019 Jul 9:74(1):36-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.056. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31272550]

Jain SP, Ventura HO, Ramee SR, Collins TJ, Isner JM, White CJ. Directional coronary atherectomy in heart transplant recipients. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 1993 Sep-Oct:12(5):819-23 [PubMed PMID: 8241222]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhama JK, Nguyen DQ, Scolieri S, Teuteberg JJ, Toyoda Y, Kormos RL, McCurry KR, McNamara D, Bermudez CA. Surgical revascularization for cardiac allograft vasculopathy: Is it still an option? The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2009 Jun:137(6):1488-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.026. Epub 2009 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 19464469]

Lee MS, Tadwalkar RV, Fearon WF, Kirtane AJ, Patel AJ, Patel CB, Ali Z, Rao SV. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: A review. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2018 Dec 1:92(7):E527-E536. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27893. Epub 2018 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 30265435]