Introduction

Hemangiomas, also known as hemangiomas of infancy or infantile hemangiomas (IH), are the most common benign tumor of infancy[1]. They are often called "strawberry marks" due to their clinical appearance. Endothelial cell proliferation results in hemangiomas. There are different types of hemangiomas. Congenital hemangiomas are visible at birth whereas infantile hemangiomas appear later in infancy. Infantile angiomas are characterized by early, rapid growth followed by spontaneous involution.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of infantile hemangiomas is poorly understood, but there are several hypotheses. The most likely hypothesis suggests that hypoxic stress upregulates expression of GLUT 1 and VEGF leading to the mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells. The progenitor cells are positive for CD133 and CD31[2]. Another hypothesis suggests that placental trophoblasts serve as the origin of stem cells for hemangiomas[3]. A third hypothesis suggests that IH development involves vasculogenesis from progenitor cells (de novo formation) as well as the formation of new vessels from existing ones (angiogenesis)[2]. Angiogenic factors have been suggested to act on endothelial cells and pericytes to initiate the formation of a capillary network[4].

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangioma is the most common benign vascular tumor of infancy and affects about 4% to 5 % of newborns[5]. It is due to an abnormal cluster of small blood vessels that occurs during the first year of life. Infantile hemangiomas occur more frequently in Caucasian infants compared to other racial groups. There is also a female predominance with a female to male ratio of up to 5:1. Premature infants, babies born with low birth weights or with prenatal hypoxia are also prone to developing hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas are common in infants with elder mothers. The disorder is often seen after post chorionic villus sampling or in multiple births with twins or triplets. Most cases are sporadic but infantile hemangiomas have been seen to run in families. They have been associated with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance[6] although no specific genes are implicated.[7]

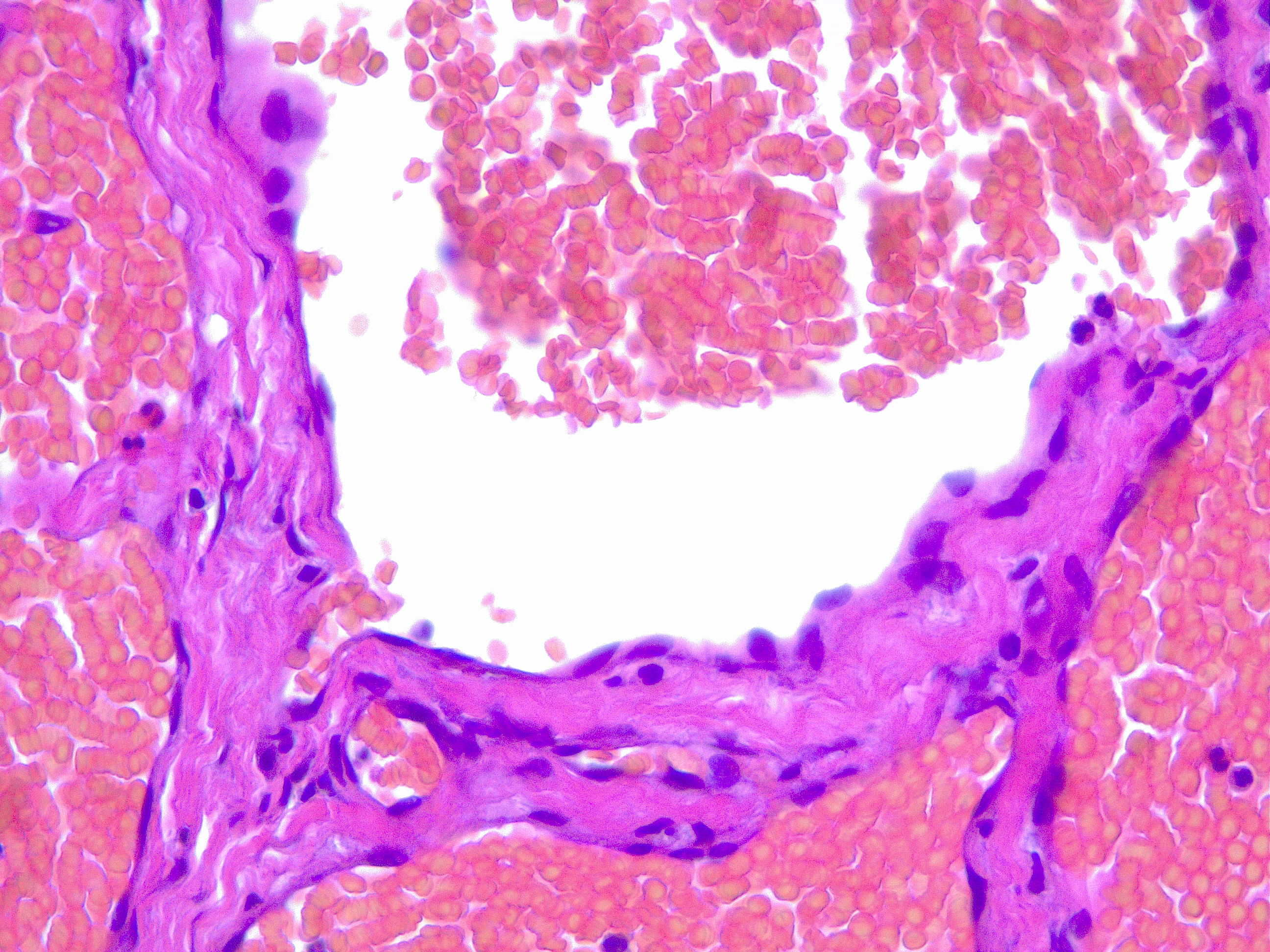

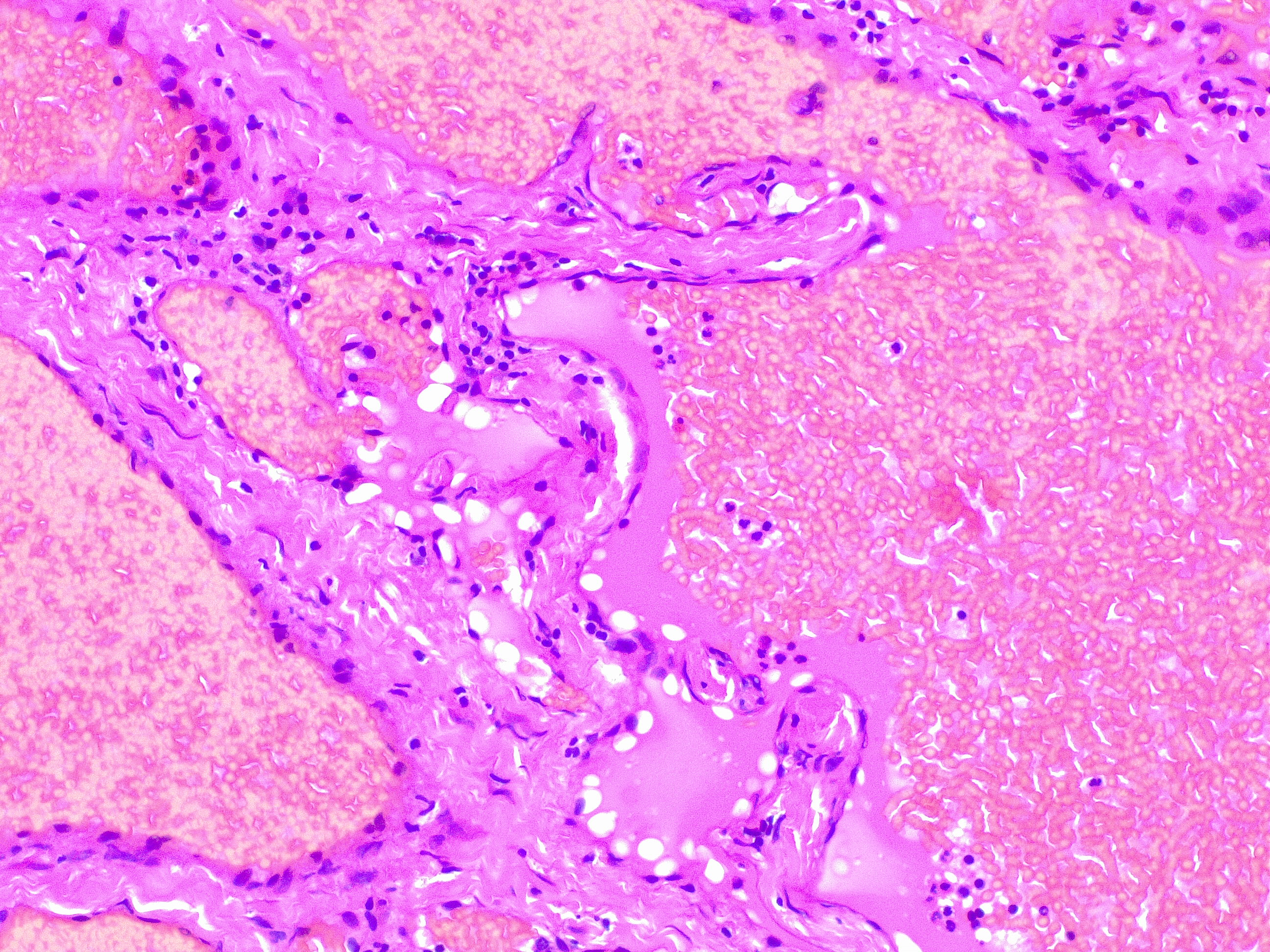

Histopathology

Upon histopathological examination of an infantile hemangioma, a multinodular pattern fed by a single arteriole can be seen[8]. The nodules are composed of hyperplastic endothelial cells, pericytes with and without lumens and prominent basement membranes. The involution stage of the hemangioma is marked by dilated vascular lumens and flattened endothelial cells (which give the IH its lobular architecture). Fibrosis becomes pronounced as involution progresses[9]. During involution, IH expresses a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase, which also inhibits angiogenesis[4]. Placenta-associated vascular antigens staining, including FcRII, Lewis Y antigen (LeY) and merosin, is also observed during involution. Upon immunohistochemical evaluation of the endothelial cells, they express CD31, von Willebrand factor, and urokinase in all phases. Infantile hemangiomas express glucose transporter protein-1 (GLUT 1) during all phases of their development. Thus, immunohistochemical studies can be used to distinguish the development stages of IH.

History and Physical

Infantile hemangioma is usually absent at birth but can present with several types of precursor lesions. These include a pale area of vasoconstriction, an erythematous macule, a telangiectatic red macule or blue bruise-like patches. Infantile hemangiomas become clinically apparent within 1 to 4 weeks. The localization is ubiquitous, and they may occur on the skin and mucosal surfaces. The majority present as a single localized cutaneous hemangioma but infantile hemangioma may be multifocal or segmental. Hemangiomas occur most commonly on the head and the neck and are seen in 60 % of cases. This is followed by lesions on the trunk in 25% of cases, and least commonly, on the extremities, seen in 15% of cases[6]. Hemangiomas can be superficial, deep or mixed with components of both superficial and deep layers. Superficial lesions involve the superficial dermis and are raised, lobulated and bright red. Deep hemangiomas, also called subcutaneous hemangiomas, arise from the reticular dermis and/or the subcutis layer, and appear as a bluish-hued nodule, plaque or tumor. Mixed hemangiomas have features of both locations.

The natural history of infantile hemangioma has a triphasic evolution:

- Early proliferative or growth phase: Usually, there is rapid growth during the first three months and gradual growth in months five to eight of life. Deep infantile hemangiomas tend to proliferate for a longer period and can be seen doing so until the ninth or twelfth month of life[3].

- Plateau phase: The lesion remains stable and quiescent for a period of months (between 6 and 12 months of life).

- Involution phase: This may occur within the first year of life and can continue for several years. The regressive infantile hemangiomas become softer and more compressible, and the color changes from bright red to purple or gray. The skin may return to normal, but often there are residual changes (excessive fibrofatty tissue, telangiectasia, skin laxity)[3][7].

Evaluation

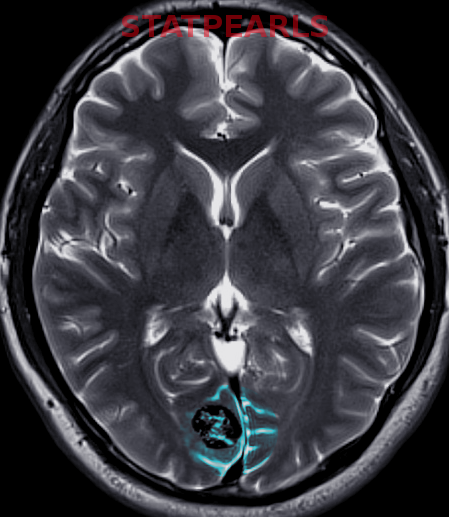

Most Infantile hemangiomas are diagnosed clinically. A skin biopsy can be performed if there is any doubt. Infantile hemangiomas stain positive for GLUT 1. Imaging studies like ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are indicated to confirm the diagnosis and the extent of deep IH without superficial changes. This is done to rule out associated anomalies and to differentiate proliferating IH from other tumors.

Treatment / Management

Most infantile hemangiomas do not require treatment because they resolve on their own. Complicated infantile hemangiomas requires treatment. Recently, beta blockers such as oral propranolol (2mg/kg/day) have been shown to be effective as first line therapy. However, the side effect profile of propanolol includes bradycardia, hypotension, bronchospasm, and hypoglycemia. Oral prednisone (2-4mg/kg/day) is an alternative therapy that can be used. The high dose of prednisone would have to be slowly tapered over weeks to months. Prednisone's adverse reactions would include irritability, sleep disturbance, hypertension, bone demineralization, cardiomyopathy, and growth retardation. The topical beta blocker, timolol, is used for smaller,superficial, and uncomplicated, infantile hemangiomas.

Intralesional and topical corticosteroids can be used to treat small focal lesions[3]. Otherwise, surgical excision may be considered to prevent complications. Surgical excision involves removing the residual fibrofatty tissue and this improves treatment outcomes.

Pulsed dye laser (PDL) is indicated for telangiectasia, but PDL remains controversial for infantile hemangiomas that are deep[10].

Differential Diagnosis

When considering hemangiomas, there are various differentials that fall into this category. It is important to consider each of them to obtain the accurate diagnosis.

- Congenital hemangioma

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

- Tufted hemangioma

- Venous malformation

- Capillary malformation: port wine stain

- Macrocystic lymphatic malformation

- Malignant tumors: sarcoma, a cutaneous location of neuroblastoma or lymphoma

Prognosis

The prognosis is very good for uncomplicated IH and there is complete involution in the majority of cases. 50% of hemangiomas will resolve in 5 years, 70% by 7 years and 90% by 9 years. Approximately 8% of IH leave cosmetic disfigurement and require some intervention.

Complications

The complications depend on the patient's age and on the hemangioma's size and location. The complications of IH are listed below.

- Ulceration is the most common complication and occurs in up to 10% of cases. Locations with higher risk of ulceration include the anogenital area, lower lip, axilla, and neck.

- Ophthalmologic complications include amblyopia, astigmatism, myopia, retrobulbar involvement and tear duct obstruction.

- Airway obstruction can be seen in nasal, subglottic and laryngeal passages.

- Difficulties feeding can be seen with perioral or lip hemangiomas.

- Visceral hemangiomatosis, especially multifocal hemangiomas (greater than or equal to 5 skin lesions), may be associated with liver or gastrointestinal involvement.

- Cosmetic disfigurement can be seen with large facial area involvement or involvement of the nasal tip (called Cyrano nose), ears and perioral area.

- PHACES syndrome manifests with a large segmental facial hemangioma (greater than or equal to 5 cm). The PHACES syndrome acronym stands for posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma of the cervicofacial region, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, eye anomalies, and Sternal or abdominal clefting[3].

- LUMBAR syndrome manifests with lumbosacral hemangiomas and may be associated with underlying developmental anomalies. The LUMBAR syndrome acronym represents lumbosacral hemangioma, urogenital anomalies, myelopathy, bony deformities, anorectal or arterial, and renal anomalies[3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The goal in identifying hemangiomas and treating them is to prevent their complications. One of the most serious complications includes permanent cosmetic disfigurement that may have a psychosocial impact on the patient and the family.

The management of IH is best done with an interprofessional approach. This would consist of a team with pediatricians, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, and other specialists.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hemangioma Investigator Group, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, Horii KA, Lucky AW, Mancini AJ, Metry DW, Newell B, Nopper AJ, Frieden IJ. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: demographic, prenatal, and perinatal characteristics. The Journal of pediatrics. 2007 Mar:150(3):291-4 [PubMed PMID: 17307549]

Yu Y, Flint AF, Mulliken JB, Wu JK, Bischoff J. Endothelial progenitor cells in infantile hemangioma. Blood. 2004 Feb 15:103(4):1373-5 [PubMed PMID: 14576053]

Holland KE, Drolet BA. Infantile hemangioma. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2010 Oct:57(5):1069-83. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.07.008. Epub 2010 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 20888458]

Takahashi K, Mulliken JB, Kozakewich HP, Rogers RA, Folkman J, Ezekowitz RA. Cellular markers that distinguish the phases of hemangioma during infancy and childhood. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1994 Jun:93(6):2357-64 [PubMed PMID: 7911127]

Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Jul 1:390(10089):85-94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00645-0. Epub 2017 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 28089471]

Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003 Apr:48(4):477-93; quiz 494-6 [PubMed PMID: 12664009]

Margileth AM, Museles M. Cutaneous hemangiomas in children. Diagnosis and conservative management. JAMA. 1965 Nov 1:194(5):523-6 [PubMed PMID: 5897362]

TOMPKINS VN, WALSH TS Jr. Some observations on the strawberry nevus of infancy. Cancer. 1956 Sep-Oct:9(5):869-904 [PubMed PMID: 13364872]

Tan ST, Velickovic M, Ruger BM, Davis PF. Cellular and extracellular markers of hemangioma. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2000 Sep:106(3):529-38 [PubMed PMID: 10987458]

Stier MF,Glick SA,Hirsch RJ, Laser treatment of pediatric vascular lesions: Port wine stains and hemangiomas. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 18068263]