Sonography Pediatric Gynecology Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Sonography Pediatric Gynecology Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Introduction

Pediatric and adolescent girls may present with a wide range of gynecologic tract pathologies, including congenital, infectious, neoplastic, and syndromic conditions. Imaging plays a crucial role in their diagnosis, with ultrasound serving as the first-line and often the only imaging modality required due to its accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and ability to be performed at the bedside. Common indications for pelvic imaging include pelvic pain, masses, ambiguous genitalia, primary amenorrhea, and precocious puberty. Pediatric ovarian tumors are rare. Radiologists, especially pediatric specialists, must be well-versed in normal ultrasound anatomy, common pelvic pathologies, and their imaging characteristics. This activity reviews ultrasound techniques, normal sonographic findings, and key interpretations, including those in emergency cases.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The uterus is a midline pelvic organ located between the urinary bladder and rectum. The ovaries are located on each side of the uterus. The uterus and ovaries vary in size according to age. The size of the uterus and ovaries varies with age. In neonates, the uterus appears relatively larger compared to later in infancy due to the influence of maternal and placental hormones. After early infancy, hormonal stimulation declines, resulting in the stabilization of uterine and ovarian size, which remains consistent until approximately age 7 to 8.

The Uterus

The uterus is prominent in neonates, measuring approximately 3.5 cm in length and 1.4 cm in width, with an echogenic endometrial line. The cervix is thicker than the fundus, with a fundus-to-cervix ratio of approximately 1:2. In the prepubertal stage, the uterus is tubular, measuring 2.5 to 4 cm long and less than 1 cm thick. At puberty, the uterus develops an adult configuration with fundal enlargement, and the fundus-to-cervix ratio shifts to 2:1 or 3:1. Uterine length ranges from 5 to 8 cm, with a width of approximately 1.5 cm. Endometrial thickness varies depending on the menstrual phase.[1][2]

A study by Gilligan et al found that in individuals with a mean age of 11.3±6.0, pelvic ultrasound measured an average uterine volume of 25.5±27.0 cm³. The mean endometrial thickness for this age group was 4.5±3.7 mm. A significant association was observed between uterine volume and endometrial thickness with age (P < .0001).[3]

The Ovaries

The ovaries undergo changes in appearance and volume throughout life, influenced by maternal hormones during infancy and by follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) during puberty.

The approximate volume of the ovaries according to age is as follows:

- Infancy: Approximately 1 cm.

- Up to 2 years: Approximately 0.67 cm.

- Up to 6 years: Less than 1 cm.

- Up to 10 years (prepubertal stage): Increases in volume, measuring approximately 1.2 to 2.3 cm.

- Premenarchal stage: Ovary measures 2 to 4 cm.

- At the time of the first growth spurt: Ovarian volume measures 8 cm, with follicular maturation occurring due to the secretion of FSH.

- Postmenarchal: Ranges between 2.5 and 20 cm.[2][4]

Gilligan et al measured a mean right ovarian volume of 4.5±4.7 cm³ and a mean left ovarian volume of 4.0±4.1 cm³ in 889 patients aged 0 to 20. The right ovary was significantly larger than the left (P = .0126).[3]

Indications

Indications for pelvic ultrasound in children include:

- Ambiguous genitalia

- Screening for congenital anomalies or malformations

- Pelvic pain

- Primary amenorrhea

- Pelvic swelling or mass

- Prepubertal bleeding

- Precocious puberty

- Irregular menses

- Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents

- Ectopic pregnancy in adolescents

Contraindications

Pediatric ultrasound has no absolute contraindications, as it is a noninvasive, radiation-free imaging modality. However, relative contraindications may include open wounds, severe skin infections, or recent surgical sites in the area being examined, which could cause discomfort or hinder the effectiveness of the scan.

Equipment

An ultrasound machine with an appropriate transducer is essential for imaging. Ultrasound gel is applied as a conductive medium between the skin and transducer to ensure optimal transmission of ultrasound waves. For transabdominal ultrasound in adolescents, a curved or convex array transducer with a frequency of 3 to 5 MHz is used. In smaller children and infants, a 5 to 9 MHz linear transducer is preferred. A linear transducer is particularly effective for transperineal ultrasound in neonates and infants. A 12 MHz linear transducer is helpful for distinguishing bowel, fat, muscles, and lymph nodes near pelvic organs.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) is not typically performed in children but may be used in sexually active adolescents to complement transabdominal imaging. This technique involves inserting a long, high-frequency, wand-shaped transducer into the vagina to enhance visualization of pelvic structures, particularly the endometrium.[5] Color Doppler mode provides valuable information on the vascularity of the ovaries, uterus, and lesions, while spectral Doppler is essential for obtaining vascular waveforms, which aid in diagnosing conditions such as ovarian torsion.

Personnel

A certified and registered ultrasound technologist conducts the examination, capturing both static and dynamic images for the radiologist to review. Radiologists may directly conduct the ultrasound in certain cases to obtain additional imaging or clarify diagnostic findings.

Additionally, pediatricians, gynecologists, surgeons, and emergency medicine physicians collaborate in patient evaluation and management. Nurses or medical assistants may assist with patient preparation, thereby ensuring patient comfort and providing post-examination care to facilitate a smooth and effective imaging process.

Preparation

A full bladder is necessary for transabdominal ultrasound to ensure proper visualization of the pelvic organs. The fluid in the bladder displaces the gas-filled colon and acts as an acoustic window, improving the visibility of pelvic structures. Therefore, the patient is instructed to drink water and hold her urine before the examination. The bladder can be retrogradely filled by placing a bladder catheter in children who lack bladder control. The patient lies supine on the bed, with the area to be scanned exposed and the rest of the abdomen covered with a drape.

Sexually active adolescent patients are instructed to void before a TVS examination. The patient is then positioned in the lithotomy position for the procedure.

Technique or Treatment

The transabdominal approach is usually sufficient for visualizing pelvic structures in neonates and young children. In transabdominal ultrasound, the patient lies supine, and imaging is performed by placing a transducer on the lower abdomen, utilizing a distended urinary bladder as an acoustic window.

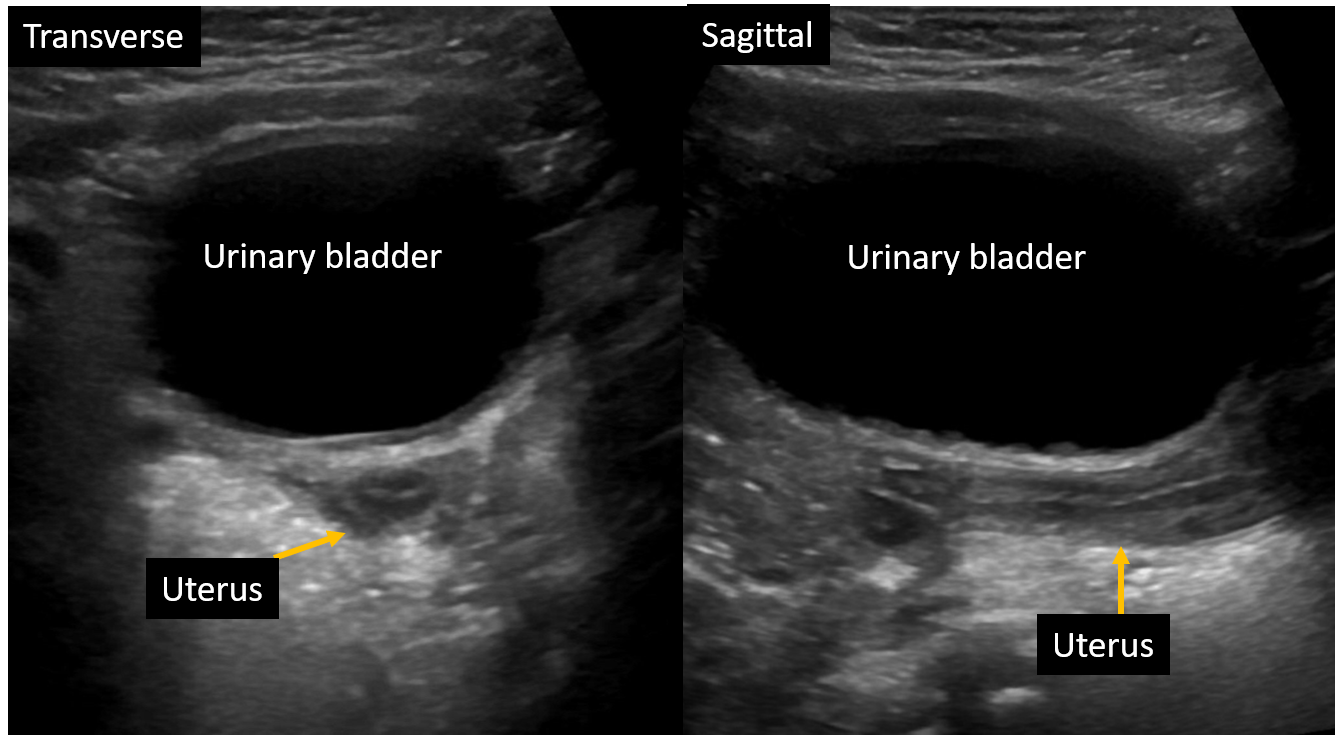

Transperineal or translabial ultrasound is performed for evaluating labial masses, hydrometrocolpos, anal atresia, or urogenital malformations. In transperineal ultrasound, the transducer is placed directly on the introitus, capturing longitudinal and transverse images of the vagina, uterus, and ovaries (see Image. Translabial Ultrasound Showing Normal Pelvic Anatomy in a 2-Year-Old Female).

TVS can be performed in sexually active adolescents, and images can be obtained by introducing a high-frequency probe into the vagina. This technique provides high-resolution imaging for diagnosing early intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy and is also valuable for identifying adnexal masses.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is an emerging technique used for imaging the female pelvis in adults. CEUS uses intravenous ultrasound contrast agents, consisting of 1 to 10 µm microspheres of gas enclosed in a phospholipid or polymeric shell. The technique utilizes a low mechanical index, contrast-specific mode with a stationary probe focused on the area of interest. Both B-mode and contrast mode are displayed simultaneously on a split screen, allowing for the acquisition of cine and static images.[6]

The uteri and ovaries of children and adolescents can be scanned using convex transducers with frequencies ranging from 1 to 9 MHz. A dose of 0.03 to 0.10 mL/kg of SonoVue/Lumason is considered sufficient for pediatric small organ imaging.[7]

Interpretation

Normal ultrasound findings

- Prepubertal uterus: The uterus is visible posterior to the fluid-filled bladder (see Image. Transabdominal Ultrasound of Normal Tubular-Shaped Uterus in a 2-Year-Old Female). The uterus appears as a tubular structure on longitudinal sections and maintains this shape until 2 to 3 years before puberty. The endometrium appears as a hyperechoic line. Occasionally, fluid may be present within the uterine cavity of a neonate due to maternal hormonal influence. During infancy, the cervix and uterine body are of similar size. Prepubertal ovaries appear as ovoid hypoechoic structures with small follicles, which appear as well-defined, tiny cysts. In the transverse plane, ovaries are located on either side of the uterine cornua (see Image. Transabdominal Ultrasound of Uterine Didelphys). Ovarian volume is measured using the simplified formula—(Length × Width × Depth) × 1/2—based on measurements obtained from longitudinal and transverse sections. The vaginal canal is visible distal to the cervix and anterior to the rectum. Pulsed Doppler of the uterine artery shows a narrow systolic waveform.

- Postpubertal uterus: During puberty, the uterine fundus grows more than the cervix, resulting in a pear-shaped uterus and an increase in volume. The endometrial thickness varies according to the menstrual cycle phase, being thickest during the post-ovulatory and near-premenstrual phases (see Image. Normal Transabdominal Ultrasound of the Uterus in a 17-Year-Old Female).[1] The ovaries also enlarge with the development of a dominant follicle in one ovary. The pulsed color Doppler of the uterine artery reveals broad systolic waveforms and positive diastolic flow.

Abnormal ultrasound findings

- Müllerian anomalies: Female reproductive tract anomalies may result from agenesis or hypoplasia, vertical or lateral fusion abnormalities, or resorption defects.

- Agenesis: Müllerian agenesis, also known as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, is characterized by features of vaginal atresia, a rudimentary or absent uterus, and normal ovaries on ultrasound. The rudimentary uterus can be unicornuate or bicornuate, and if it has a functioning endometrium, hematometra may occur due to associated vaginal atresia. This condition can also be associated with renal, auditory, and skeletal anomalies.

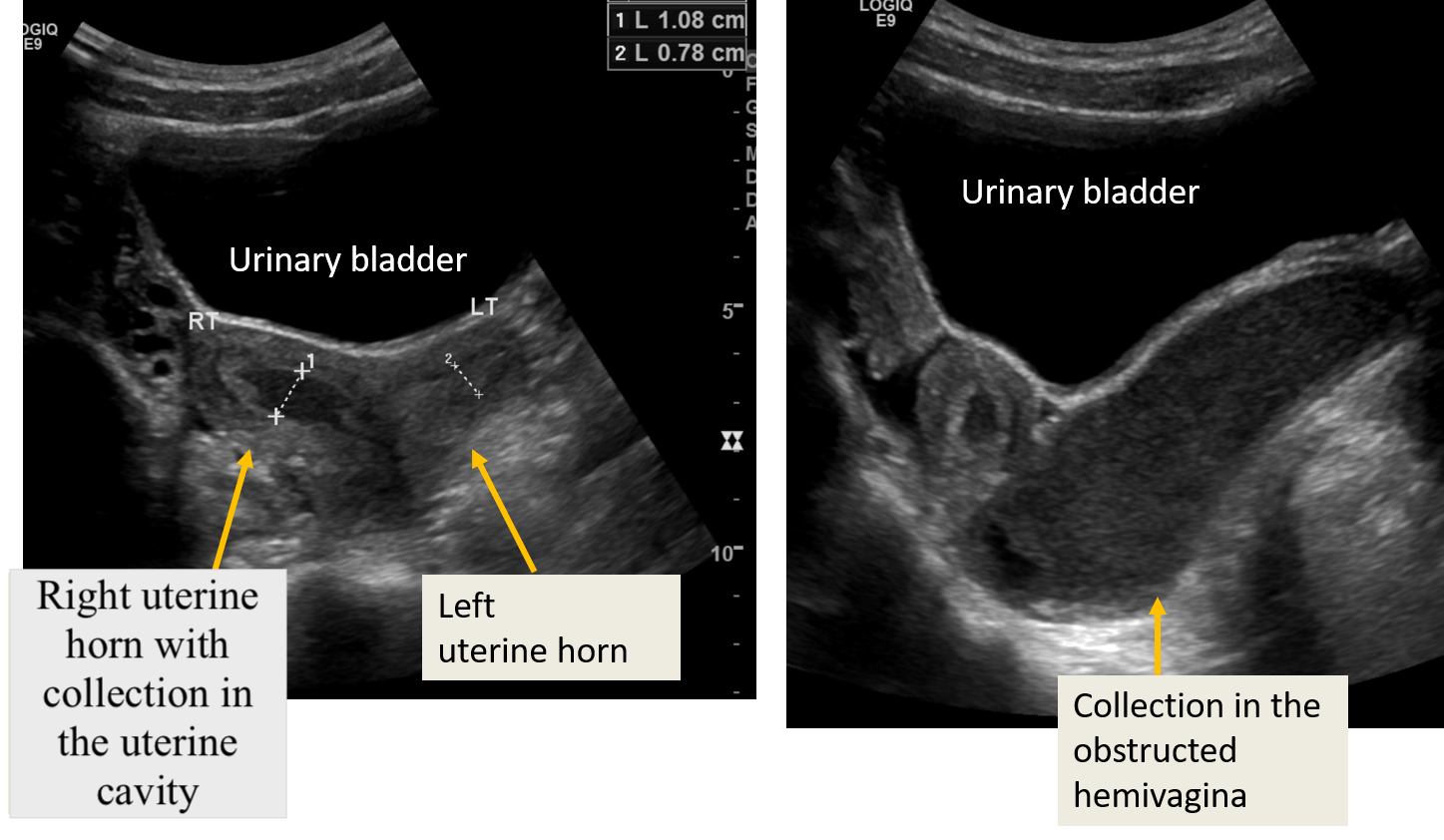

- Obstructive Müllerian anomalies: These conditions include vaginal septum, imperforate hymen, or cervical dysgenesis. Neonates may present with hydrocolpos, mucocolpos, or hydrometrocolpos, caused by the accumulation of secretions in the vagina or endometrial cavity and vagina under the influence of maternal hormones. An obstructed, mucus-filled uterus and vagina appear as a cystic mass in the pelvis. In adolescents, menstrual fluid can accumulate in the uterine, cervical, and vaginal cavities, resulting in hematometrocolpos. The ultrasound may show fluid with debris in the endometrial and vaginal cavities, and occasionally in the fallopian tubes as well. Obstructed hemivagina with ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA), also known as Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich (HWW) syndrome, is another Müllerian anomaly. This is characterized by uterine didelphys with obstruction of one hemivagina, leading to fluid accumulation in the affected hemivagina and ipsilateral uterine horn. This condition is also associated with ipsilateral renal anomalies, which can include renal agenesis (see Image. Transabdominal Ultrasound of Obstructed Hemivagina With Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly).[8]

- Nonobstructed Müllerian anomalies: Defects in the lateral fusion of the Müllerian ducts can lead to bicornuate, didelphys, or unicornuate uteri, which are identifiable on ultrasound as duplicated uterine horns, with or without separate cervices and/or a septated vagina. An incomplete uterine septum, also resulting from the fusion defect, can be challenging to identify on ultrasound unless the uterine cavity is filled with fluid.

- Turner syndrome: This is an X chromosomal abnormality characterized by a 45,XO karyotype. The ovaries are fibrous, streak-like, and typically not visible on ultrasound. The uterus remains prepubertal in size, although spontaneous puberty may occur in a few patients.[9]

Non-Congenital Pathology

- Pelvic inflammatory disease: Early pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) changes are subtle on ultrasound, presenting as hyperemia and thickening of pelvic structures, along with free fluid in the cul-de-sac. Chronic PID may lead to pyosalpinx, pyometra, or tubo-ovarian abscess. Pyosalpinx appears as a thick-walled, tubular, round, or oval structure with low-level internal echoes. When the ovary is involved, it becomes enlarged and echogenic. A tubo-ovarian abscess appears as a complex collection with moving echoes and debris.[10]

- Ectopic pregnancy: This condition can occur in adolescent girls, although the incidence is lower than in adults, and is often associated with sexually transmitted diseases, inflammation, or PID, especially involving fallopian tubes. Extrauterine pregnancies can occur in the cervix, abdomen, ovary, or uterine cornua, appearing as an echogenic ring with an anechoic area. The yolk sac is typically not visible in early pregnancy. A ruptured ectopic pregnancy may present with a hematoma, seen as a hyperechoic lesion, and hemoperitoneum, which appears as a fluid with echoes in the peritoneal cavity. Early diagnosis is crucial, as it can lead to hemodynamic instability.[11][12]

- Torsion: Ovarian torsion occurs when the ovary twists around its supporting ligaments, including the utero-ovarian and infundibulopelvic ligaments. The fallopian tube may also be involved in adnexal torsion. Most cases occur in individuals of childbearing age, with only 20% seen in premenarchal patients. Typical features of torsion include an enlarged, edematous ovary with hyperechoic central stroma and multiple small follicles (8-12 mm) located peripherally.[13] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Ovarian Torsion," for more information.

- Torsion leads to venous and lymphatic obstruction, causing the twisted ovary to become engorged. This appears edematous and enlarged compared to the normal contralateral ovary. Blood supply to the ovary may be decreased or absent, though it is rare to observe completely absent vascular flow due to the ovary's dual blood supply from the uterine and ovarian arteries.[14]

- Venous flow is typically obstructed in ovarian torsion. Color Doppler often reveals twisting of the ovarian vascular pedicle. A "follicular ring sign" may be seen, which is characterized by a hyperechoic ring around the antral ovarian follicles due to perifollicular edema.[13] An ovarian mass greater than 5 cm increases the likelihood of torsion, and ultrasound can detect these associated masses. Early research suggests that CEUS can help confirm equivocal cases by identifying a lack or reduction in parenchymal enhancement.[6]

- Foreign body: Foreign bodies, such as toilet paper, are commonly seen in pediatric patients, particularly in young females who may insert objects into the vaginal cavity. Vaginal foreign bodies can also be associated with sexual abuse. Ultrasound is an effective tool for identifying foreign bodies, which typically appear echogenic, with or without posterior acoustic shadowing. Translabial ultrasound can enhance visualization of the vaginal cavity for accurate assessment.

Benign Masses

- Simple cyst: Simple ovarian cysts appear as thin-walled, anechoic lesions and are most commonly seen in adolescent or postpubertal girls, although they can occur at any age. In postpubertal girls, these cysts form when the dominant follicle fails to regress or rupture. Dominant follicles are usually less than 0.9 cm in size. Follicular cysts less than 2 cm are generally functional and physiological. Cysts larger than 2 cm are considered pathological if they do not regress over time and should be followed up after 6 weeks for further evaluation.[5]

- Hemorrhagic cyst: A hemorrhagic cyst typically develops in the corpus luteum and is often associated with pelvic pain. The appearance of hemorrhage on ultrasound varies; acute hemorrhage appears hyperechoic compared to the ovarian stroma. As time progresses, the cyst becomes heterogeneous with multiple thin septa and low-level echoes. These cysts usually regress spontaneously over time. Follow-up ultrasound is recommended after 6 to 12 weeks for further evaluation.

- Mature cystic teratoma or dermoid cyst: A mature teratoma, or dermoid cyst, is a benign ovarian mass containing components from all 3 germ cell layers—mesoderm, ectoderm, and endoderm. The lesion appears as a heterogeneous solid and cystic mass. This is the most common pediatric ovarian mass. The cyst may show fluid-fluid levels due to varying densities of fluid and fat. Calcifications typically present as hyperechoic foci with posterior acoustic shadowing. Fat within the mass is also hyperechoic but lacks shadowing and can be challenging to distinguish from bowel gas. Additional imaging with computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance image (MRI) with fat saturation may provide additional diagnostic information.[15]

- Cystadenoma: These epithelial tumors are classified into serous and mucinous types. Serous cystadenomas appear as thin-walled, usually unilocular masses with a wall thickness of less than 3 mm. They may have thin septations and papillary projections. These masses can be unilateral or bilateral (20%) and are typically smaller than mucinous cystadenomas. Mucinous cystadenomas are larger, multilocular masses with multiple thin septations and contain mucin, which appears as low-level internal echoes. While these imaging characteristics are suggestive, histology is required for definitive diagnosis. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Ovarian Cystadenoma," for more information.

Malignant Masses

- Immature teratoma: Immature teratomas are most commonly observed in postmenarchal females. These tumors are predominantly solid and consist of immature tissue from all 3 germ cell layers. They may coexist with mature cystic teratomas. On ultrasound, immature teratomas appear as heterogeneous solid masses with hyperechoic foci from scattered calcifications and fat. Differentiating between immature and mature teratomas can be challenging, but a solid mass with numerous cystic components is more indicative of an immature teratoma, whereas a predominantly cystic lesion suggests a mature teratoma.

- Cystadenocarcinoma: Cystadenocarcinomas present with solid components, associated ascites, papillary projections, and thick, irregular septations, often accompanied by increased vascularity, all of which suggest malignancy. Color Doppler can help differentiate malignant from benign tumors. Malignant tumors typically show central angiogenesis, with vascularity in the core of the lesion, while benign tumors usually have peripheral vascularity. Spectral Doppler analysis may reveal low-resistance flow, characterized by high diastolic flow and reduced variation in systolic-diastolic waveforms.[16]

- Sex cord-stromal tumor: Sex cord-stromal tumors arise from granulosa, theca, or Sertoli cells. These tumors include a juvenile variety (juvenile granulosa cell tumor or JGCT) that typically occurs in prepubertal girls and young women aged 30 or younger. Most of these tumors are mixed solid and cystic but can also appear as entirely solid or cystic masses. The juvenile variety is usually multicystic, with irregular septations that appear "sponge-like" on ultrasound, along with variable solid components. Granulosa-theca cell tumors are often associated with elevated estrogen levels, leading to isosexual precocious puberty, an enlarged uterus, and a thickened endometrial lining.[17] Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors may cause virilization due to androgen production.

- Rhabdomyosarcoma: Rhabdomyosarcoma is a soft tissue tumor that most commonly affects urogenital sinus remnants, including the uterus and vagina. Uterine involvement typically results from the extension of a vaginal mass. These malignancies are most commonly seen in girls aged 2 to 6 and 14 to 18. The most common types are embryonal and botryoid (sarcoma botryoides), which appear as heterogeneous masses on ultrasound.[18]

- Ovarian-adnexal reporting and data system: This system (O-RADS) was developed to standardize reporting and risk assessment for adnexal and ovarian masses. The system utilizes a lexicon from the O-RADS ultrasound working group, published in 2018, but still requires external validation.[19] This system has been proven accurate in assigning risk and management recommendations for ovarian and adnexal masses. The study has demonstrated accuracy in assigning risk and management recommendations for ovarian and adnexal masses, with high inter-reader agreement regardless of training experience level.[20] Although this system was designed for adult adnexal masses, it can also be applied to pediatric cases.

A retrospective study conducted in the United Kingdom demonstrated that ovarian masses, whether benign or malignant, have the potential for recurrence. Follow-up is recommended both after the primary diagnosis and post-resection.[21]

Complications

Ultrasound examinations generally have no obvious complications. Pediatric sonography is a safe, noninvasive imaging technique with minimal risk; however, certain challenges may arise. Patient discomfort, especially in cases requiring prolonged scanning or pressure application, can make imaging difficult. In infants and young children, movement and lack of cooperation may result in suboptimal images, occasionally requiring additional scans or sedation in rare cases. Furthermore, misinterpretation of normal developmental variations as pathology may lead to unnecessary follow-up tests or interventions.

Clinical Significance

Ultrasound is a safe, radiation-free, and readily available imaging procedure that can be easily performed at the bedside. The portability and accessibility of ultrasound make it essential in the initial evaluation of pediatric gynecological conditions. In many cases, ultrasound provides a definitive diagnosis and can also identify cases requiring further evaluation with MRI or CT scans. Emerging techniques such as CEUS have become valuable adjuncts to routine ultrasound for assessing various pathologies, such as tumoral angiogenesis, distinguishing benign from malignant lesions, and evaluating emergency conditions such as ovarian torsion.[6]

Pediatric radiologists must have a comprehensive understanding of the normal ultrasound appearance of the female pelvis across all developmental stages—from neonate to adolescent or postpubertal age. Familiarity with the sonographic features of various pelvic pathologies is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate clinical management. For example, recognizing the characteristic ultrasound findings of ovarian torsion is essential for timely intervention, which may help preserve ovarian function.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective pediatric sonography depends on an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals working collaboratively to ensure an accurate diagnosis. A fully distended urinary bladder is essential for proper ultrasound assessment of the pelvic organs in females, as it provides an acoustic window for optimal visualization of the pelvic structures. In nonemergency cases, patients with bladder control should be instructed to hold their urine before the scan. The referring physician or assistant should communicate this requirement to the patients and their parents. Clear communication between the ordering physician and the scheduling nurse can help prevent unnecessary delays in the scanning process.

In emergency situations or in patients without bladder control, the urinary bladder can be filled retrogradely using a catheter. Effective communication among ultrasound technologists, ordering physicians, and nurses performing catheterization ensures optimal imaging and enhances patient care. Point-of-care ultrasonography performed by an emergency physician has demonstrated 100% sensitivity in diagnosing ectopic pregnancy in pediatric patients. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial in reducing treatment delays for ruptured ectopic pregnancy.[22]

Timely and effective communication of critical findings to emergency physicians and gynecologists is essential for prompt treatment. Specialty-trained nursing staff can assist in the procedure, further enhancing efficiency. Strong interprofessional coordination improves patient outcomes and ensures optimal results.

A study by Dupont et al found that implementing strategies such as assessing ultrasound readiness and eliminating invasive bladder-filling procedures reduced turnaround time from 112.4 to 101.6 minutes.[23] This improvement has a significant impact on managing surgical emergencies, such as ovarian torsion. Adopting these methods requires collaboration across various departments, including technologists, emergency personnel, radiologists, and the surgical team. By fostering a team-based approach and prioritizing communication, healthcare professionals can enhance patient-centered care, improve diagnostic accuracy, ensure patient safety, and optimize overall performance in pediatric sonography.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Transabdominal Ultrasound of Obstructed Hemivagina With Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly. Transabdominal ultrasound images show transverse sections of the pelvis and 2 separate uterine horns. The right uterine horn and hemivagina appear obstructed, with an echogenic collection consistent with blood products in the vaginal cavity. No fluid collection is observed in the left uterine horn.

Contributed by P Sandhu, MD

References

Hagen CP, Mouritsen A, Mieritz MG, Tinggaard J, Wohlfahrt-Veje C, Fallentin E, Brocks V, Sundberg K, Jensen LN, Juul A, Main KM. Uterine volume and endometrial thickness in healthy girls evaluated by ultrasound (3-dimensional) and magnetic resonance imaging. Fertility and sterility. 2015 Aug:104(2):452-9.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.04.042. Epub 2015 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 26051091]

Garel L, Dubois J, Grignon A, Filiatrault D, Van Vliet G. US of the pediatric female pelvis: a clinical perspective. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2001 Nov-Dec:21(6):1393-407 [PubMed PMID: 11706212]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGilligan LA, Trout AT, Schuster JG, Schwartz BI, Breech LL, Zhang B, Towbin AJ. Normative values for ultrasound measurements of the female pelvic organs throughout childhood and adolescence. Pediatric radiology. 2019 Jul:49(8):1042-1050. doi: 10.1007/s00247-019-04419-z. Epub 2019 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 31093723]

Cohen HL, Tice HM, Mandel FS. Ovarian volumes measured by US: bigger than we think. Radiology. 1990 Oct:177(1):189-92 [PubMed PMID: 2204964]

Stranzinger E, Strouse PJ. Ultrasound of the pediatric female pelvis. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2008 Apr:29(2):98-113 [PubMed PMID: 18450135]

Olinger K, Liu X, Khoshpouri P, Khoshpouri P, Scoutt LM, Khurana A, Chaubal RN, Moshiri M. Added Value of Contrast-enhanced US for Evaluation of Female Pelvic Disease. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2024 Feb:44(2):e230092. doi: 10.1148/rg.230092. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38175802]

Piskunowicz M, Back SJ, Darge K, Humphries PD, Jüngert J, Ključevšek D, Lorenz N, Mentzel HJ, Squires JH, Huang DY. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the small organs in children. Pediatric radiology. 2021 Nov:51(12):2324-2339. doi: 10.1007/s00247-021-05006-x. Epub 2021 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 33830288]

Mishra N, Ng S. Sonographic diagnosis of Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly Syndrome: a report of two cases. Australasian journal of ultrasound in medicine. 2014 Nov:17(4):153-158. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2014.tb00238.x. Epub 2015 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 28191231]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShawker TH, Garra BS, Loriaux DL, Cutler GB Jr, Ross JL. Ultrasonography of Turner's syndrome. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 1986 Mar:5(3):125-9 [PubMed PMID: 3517358]

Revzin MV, Mathur M, Dave HB, Macer ML, Spektor M. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Multimodality Imaging Approach with Clinical-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2016 Sep-Oct:36(5):1579-96. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150202. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27618331]

Vichnin M. Ectopic pregnancy in adolescents. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2008 Oct:20(5):475-8. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32830d0ce1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18797271]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAndrade AG, Rocha S, Marques CO, Simões M, Martins I, Biscaia I, F Barros C. Ovarian ectopic pregnancy in adolescence. Clinical case reports. 2015 Nov:3(11):912-5. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.336. Epub 2015 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 26576271]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSsi-Yan-Kai G, Rivain AL, Trichot C, Morcelet MC, Prevot S, Deffieux X, De Laveaucoupet J. What every radiologist should know about adnexal torsion. Emergency radiology. 2018 Feb:25(1):51-59. doi: 10.1007/s10140-017-1549-8. Epub 2017 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 28884300]

Huang C, Hong MK, Ding DC. A review of ovary torsion. Tzu chi medical journal. 2017 Jul-Sep:29(3):143-147. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_55_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28974907]

Outwater EK, Siegelman ES, Hunt JL. Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2001 Mar-Apr:21(2):475-90 [PubMed PMID: 11259710]

Jeong YY, Outwater EK, Kang HK. Imaging evaluation of ovarian masses. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2000 Sep-Oct:20(5):1445-70 [PubMed PMID: 10992033]

Heo SH, Kim JW, Shin SS, Jeong SI, Lim HS, Choi YD, Lee KH, Kang WD, Jeong YY, Kang HK. Review of ovarian tumors in children and adolescents: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2014 Nov-Dec:34(7):2039-55. doi: 10.1148/rg.347130144. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25384300]

Ratani RS, Cohen HL, Fiore E. Pediatric gynecologic ultrasound. Ultrasound quarterly. 2004 Sep:20(3):127-39 [PubMed PMID: 15322390]

Andreotti RF, Timmerman D, Strachowski LM, Froyman W, Benacerraf BR, Bennett GL, Bourne T, Brown DL, Coleman BG, Frates MC, Goldstein SR, Hamper UM, Horrow MM, Hernanz-Schulman M, Reinhold C, Rose SL, Whitcomb BP, Wolfman WL, Glanc P. O-RADS US Risk Stratification and Management System: A Consensus Guideline from the ACR Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting and Data System Committee. Radiology. 2020 Jan:294(1):168-185. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019191150. Epub 2019 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 31687921]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePhillips CH, Guo Y, Strachowski LM, Jha P, Reinhold C, Andreotti RF. The Ovarian/Adnexal Reporting and Data System for Ultrasound: From Standardized Terminology to Optimal Risk Assessment and Management. Canadian Association of Radiologists journal = Journal l'Association canadienne des radiologistes. 2023 Feb:74(1):44-57. doi: 10.1177/08465371221108057. Epub 2022 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 35831958]

Braungart S, CCLG Surgeons Collaborators, Craigie RJ, Farrelly P, Losty PD. Ovarian tumors in children: how common are lesion recurrence and metachronous disease? A UK CCLG Surgeons Cancer Group nationwide study. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2020 Oct:55(10):2026-2029. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.10.059. Epub 2019 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 31837839]

Le Coz J, Orlandini S, Titomanlio L, Rinaldi VE. Point of care ultrasonography in the pediatric emergency department. Italian journal of pediatrics. 2018 Jul 27:44(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0520-y. Epub 2018 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 30053886]

Dupont AS, Drayna PC, Nimmer M, Baumer-Mouradian SH, Wirkus K, Thomas DG, Boyd K, Chinta SS. Improving Turnaround Time of Transabdominal Pelvic Ultrasounds with Ovarian Doppler in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatric quality & safety. 2024 May-Jun:9(3):e730. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000730. Epub 2024 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 38807584]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence