Introduction

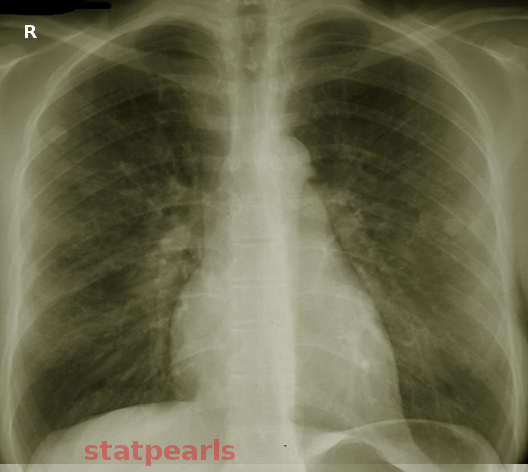

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is a disease process that results in acute hypoxia secondary to a rapid deterioration in respiratory status (see Image. Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema). The disease process has multiple etiologies, requiring prompt recognition and intervention. Increased capillary permeability and changes in pressure gradients within the pulmonary capillaries and vasculature are mechanisms for noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. To differentiate from cardiogenic pulmonary edema, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure is not elevated and remains less than 18 mmHg.[1][2] It is important to differentiate as management changes based on this distinction. Other findings during the patient's initial evaluation may include a lack of acute cardiac disease or inappropriate fluid balance, flat neck veins, and the absence of peripheral edema. Chest imaging may reveal a peripheral distribution of bilateral infiltrates with no evidence of excessive pulmonary vasculature congestion or cardiomegaly. An echocardiogram may also be used to confirm a lack of acute systolic or diastolic dysfunction.

These findings suggest a noncardiogenic source. Arguably, the most recognized form of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is a noncardiogenic pulmonary edema that has an acute onset secondary to an underlying inflammatory process such as sepsis, pneumonia, gastric aspiration, blood transfusion, pancreatitis, multisystem trauma or trauma to the chest wall, or drug overdose.[3] Diagnosis of ARDS also requires bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph with a ratio of the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) to be less than 300 mmHg with positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cmH2O. Clinical context also necessitates no evidence of acute heart failure or hypervolemia in the setting of ARDS. The scope of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is much broader than ARDS. It includes other etiologies, including high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), neurogenic pulmonary edema, opioid overdose, salicylate toxicity, pulmonary embolism, reexpansion pulmonary edema, reperfusion pulmonary edema, and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). Treatment is specific to the underlying etiology, and all require prompt recognition as clinical decline can be rapid and severe.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema has a variety of etiologies that include:

Epidemiology

Most different etiologies of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema are rare but essential to include in the broad differential diagnosis in the appropriate clinical setting. ARDS affects roughly 200000 patients in the United States, 75000 of which are associated with mortality. ARDS is also responsible for 10% of intensive care unit admissions globally.[1] HAPE is a rare disease that does not have a systematic epidemiologic analysis; however, those with risk factors for acute mountain sickness with an ascent to altitudes greater than 2250 meters are at risk for HAPE.[6] TRALI is the leading cause of death from a blood transfusion and is more commonly seen in critically ill patients, as these patients often require more transfused blood products and can be found in 1 of 5000 units of packed red blood cells. TRALI also has increased incidence in blood products with a higher ratio of plasma content, with 1 in 2000 plasma containing components and 1 in 400 whole blood products. Female donors have a higher incidence of TRALI; this was thought to be due to human leukocyte antigen antibiotics found in parous female donors.[7]

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathology is at the microvascular level due to increased pulmonary vascular pressure. In addition to this, the capillaries also become leaky, causing the formation of edema. The imbalance between the hydrostatic and oncotic forces and the enhanced permeability of the pulmonary capillaries results in pulmonary edema.[8] The capillaries become permeable due to underlying causes such as sepsis, pancreatitis, etc.

History and Physical

History includes a patient who has had progressive worsening of respiratory status and increasing dyspnea. Depending on the specific etiology, this could happen very rapidly. A thorough evaluation should occur as disease processes such as ARDS can occur in the setting of an increased inflammatory response in the body, such as sepsis, trauma, pneumonia, and pancreatitis. History should also include medication review, specifically opioid and salicylate use, as these can rarely cause noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Recent or current blood transfusions, risk factors for pulmonary embolism, and recent thoracic surgery should be considered. With appropriate geography, rapid ascent with increasing altitude may cause noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, and this should warrant further inquiry if suspected. The physical examination can rule out a cardiogenic source of pulmonary edema. Flat neck veins, appropriate fluid balance, and lack of peripheral edema are findings in noncardiogenic pulmonary edema.[9][10]

Evaluation

The evaluation should exclude a cardiogenic source; this can be done by echocardiogram to assess any changes in left ventricular ejection fraction or acute changes in the heart's systolic or diastolic function. Suppose the etiology is unclear from physical examination or echocardiogram, and a definitive evaluation is possible by assessing pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. In that case, wedge pressure of less than 18 mmHg will rule out a cardiogenic etiology. Chest imaging should be next, which, if ARDS is of concern, shows bilateral infiltrates. Arterial blood gas reveals a PaO2/FiO2 ratio (P/F ratio) of less than 300 in ARDS.[11] Reexpansion and reperfusion pulmonary edema may cause unilateral pulmonary edema. TRALI should be considered in a patient with respiratory decline and hypoxia within 6 hours of a blood transfusion.[12]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema involves addressing the underlying cause of the event. There are currently no treatment options to address the vascular permeability in ARDS. Therefore, management involves supportive care and treatment of the underlying disease until the acute lung injury is resolved. Inhaled nitric oxide, prostacyclin, anti-inflammatory therapy, and high-frequency ventilation have not shown consistent clinical benefits.[13] The other causes of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema are managed similarly with supportive care, including supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation, if needed, and addressing the inciting cause.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis should include cardiogenic pulmonary edema, as this is a cause of pulmonary edema that needs to be ruled out. In the appropriate clinical context with systemic inflammation, sepsis, or severe injury, evaluation for ARDS is necessary. HAPE should be a diagnostic option if the history shows a quick ascent in altitude. Medication and drug use should be reviewed to assess for salicylate toxicity and opioid overdose, as these often get overlooked as etiologies of pulmonary edema.[14][15] Pulmonary embolism should always be considered if presenting with dyspnea, tachycardia, or signs of hemodynamic instability. Reexpansion and reperfusion pulmonary edema should also be in the differential, and the provider should consider TRALI if pulmonary edema and hypoxia present within 6 hours of a blood transfusion.[16] The following list of differentials should be reviewed:

- ARDS

- Drug overdose from opioids and salicylates

- HAPE

- Pulmonary embolism

- TRALI

Prognosis

The prognosis varies depending on the cause of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Severe ARDS carries a 40% mortality rate. HAPE occurs in 60% of patients who ascend above 4500 meters and have a previous diagnosis of HAPE.[17] Prognosis is poor in neurogenic pulmonary edema as this condition is associated with an insult to the central nervous system; 71% of those with intracranial hemorrhage were documented to have NPE. However, there are no statistics concerning NPE in the context of other neurologic conditions such as epilepsy.[18] Ischemia-reperfusion injury accounts for 25% of the mortality after lung transplantation.[19] Mortality from TRALI is 5 to 10%; however, it can reach 47% in critically ill patients.[20]

Complications

The main complication from noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is ventilator-dependent respiratory failure requiring intubation and possible prolonged requirement of the ventilator, which necessitates prompt diagnosis to prevent the severity of this complication.[21]

Deterrence and Patient Education

In appropriate situations, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is preventable. Patients should be educated about HAPE if they have been found to have pulmonary edema in the setting of a rapid increase in altitude, as these patients risk a 60% chance of recurrence with a rapid ascent to greater than 4500 meters. Salicylate toxicity is a consideration in those with chronic use, and opioid users should receive education about the adverse effects of chronic opioid use and the possible sequela of pulmonary edema.[22]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional healthcare team is vital to promptly recognizing noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. The nursing staff is critical for recognizing reactions during a blood transfusion, which, if acted on, can prevent TRALI. Pharmacists can have an active role in those being prescribed opioids and salicylates and can recognize the rare adverse effects of these drugs, such as the development of pulmonary edema. ARDS can be diagnosed more promptly in the intensive care unit with the cooperation of the care team between the intensive care physician, respiratory therapist, and nursing staff. Interprofessional communication at all levels plays a key role in case management and directing optimal outcomes.

Media

References

Dries DJ. ARDS: From Syndrome to Disease: Prevention and Genomics. Air medical journal. 2019 Jan-Feb:38(1):7-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2018.11.018. Epub 2019 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 30711090]

Skalická H, Bělohlávek J. [Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome]. Casopis lekaru ceskych. 2015:154(6):273-9 [PubMed PMID: 26750623]

Diamond M, Peniston HL, Sanghavi DK, Mahapatra S. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613773]

Patti R, Ponnusamy V, Somal N, Sinha A, Sharma S, Yoon TS, Kupfer Y. Naloxone-Induced Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema. American journal of therapeutics. 2020 Nov/Dec:27(6):e672-e673. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000001037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31789629]

Clark SB, Soos MP. Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194387]

Luks AM, Swenson ER, Bärtsch P. Acute high-altitude sickness. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2017 Jan:26(143):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0096-2016. Epub 2017 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 28143879]

Cho MS, Modi P, Sharma S. Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939623]

Suhail Najim M, Ali Mohammed Hammamy R, Sasi S. Neurogenic Pulmonary Edema Following a Seizure: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case reports in neurological medicine. 2019:2019():6867042. doi: 10.1155/2019/6867042. Epub 2019 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 31687236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkunov AC, Sartmyrzaeva MA, Maripov AM, Muratali Uulu K, Mamazhakypov AT, Sydykov AS, Sarybaev AS. High Altitude Pulmonary Edema in a Mining Worker With an Abnormal Rise in Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Response to Acute Hypoxia Without Prior History of High Altitude Pulmonary Edema. Wilderness & environmental medicine. 2017 Sep:28(3):234-238. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2017.04.003. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28673745]

Bachmann M, Waldrop JE. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Compendium (Yardley, PA). 2012 Nov:34(11):E1 [PubMed PMID: 23532787]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMann A, Early GL. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Missouri medicine. 2012 Sep-Oct:109(5):371-5 [PubMed PMID: 23097941]

Fernandes Júnior CJ, Hidal JT, Barbas CS, Akamine N, Knobel E. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema complicating diabetic ketoacidosis. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 1996 Nov-Dec:2(6):379-81 [PubMed PMID: 15251497]

Malhotra A, Drazen JM. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation on shaky ground. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Feb 28:368(9):863-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1300103. Epub 2013 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 23339640]

Cohen DL, Post J, Ferroggiaro AA, Perrone J, Foster MH. Chronic salicylism resulting in noncardiogenic pulmonary edema requiring hemodialysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2000 Sep:36(3):E20 [PubMed PMID: 10977813]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRadke JB, Owen KP, Sutter ME, Ford JB, Albertson TE. The effects of opioids on the lung. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2014 Feb:46(1):54-64. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8373-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23636734]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTank S, Sputtek A, Kiefmann R. [Transfusion-related acute lung injury]. Der Anaesthesist. 2013 Apr:62(4):254-60. doi: 10.1007/s00101-013-2163-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23558721]

Korzeniewski K, Nitsch-Osuch A, Guzek A, Juszczak D. High altitude pulmonary edema in mountain climbers. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2015 Apr:209():33-8. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.09.023. Epub 2014 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 25291181]

Romero Osorio OM, Abaunza Camacho JF, Sandoval Briceño D, Lasalvia P, Narino Gonzalez D. Postictal neurogenic pulmonary edema: Case report and brief literature review. Epilepsy & behavior case reports. 2018:9():49-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2017.09.003. Epub 2017 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 29692972]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYabuki H, Watanabe T, Oishi H, Katahira M, Kanehira M, Okada Y. Muse Cells and Ischemia-Reperfusion Lung Injury. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2018:1103():293-303. doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-56847-6_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30484236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim J, Na S. Transfusion-related acute lung injury; clinical perspectives. Korean journal of anesthesiology. 2015 Apr:68(2):101-5. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2015.68.2.101. Epub 2015 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 25844126]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMatthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, Herridge M, Randolph AG, Calfee CS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2019 Mar 14:5(1):18. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0069-0. Epub 2019 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 30872586]

Sterrett C, Brownfield J, Korn CS, Hollinger M, Henderson SO. Patterns of presentation in heroin overdose resulting in pulmonary edema. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2003 Jan:21(1):32-4 [PubMed PMID: 12563576]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence