Introduction

Tyrosine kinases (TK) are proteins exclusively found in cells of multicellular animals. They play a key role as mediators in the signal transduction cascade for regulating cell division and cell death pathways. The TKs can be subdivided into two groups, receptor protein tyrosine kinase (RTK) and non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase (NRTK). The RTK category consists of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and many more minor receptor proteins. The NRTK are cytoplasmic proteins that have 9 defined families consisting of Fes/Fer, Syk/Zap70, Abl, Tec, Jak, Ack, Fak, Csk, and Src. Four other NRTK exist outside of the defined families, Srm, Rak/Frk, Brk/Sik, and Rlk/Txk. NRTKs are highly regulated proteins with fundamental cellular functions such as apoptosis and cell differentiation.[1][2]

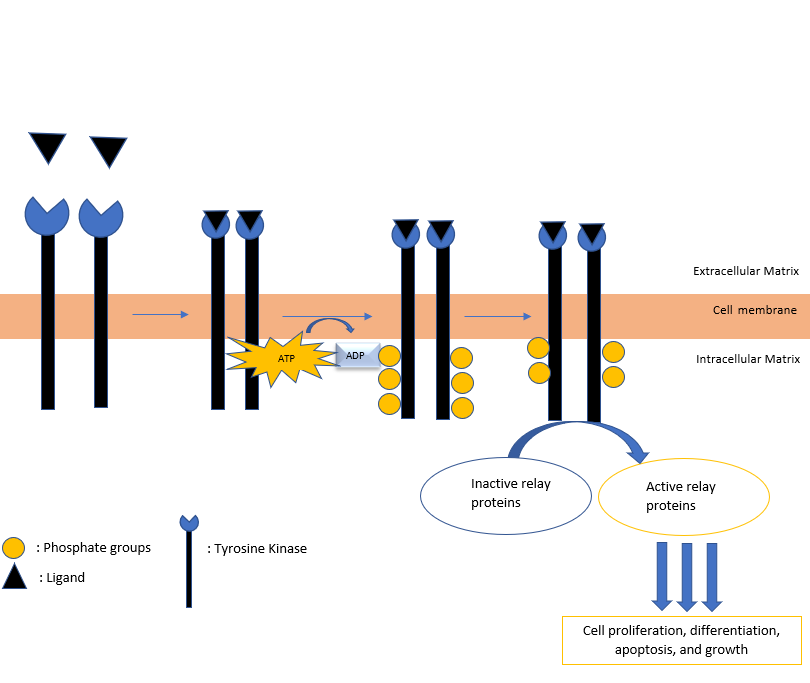

The receptor tyrosine kinases are enzymes that are transmembrane receptors on the cell surface. They typically consist of an extracellular domain that functions to bind to specific ligands. A transmembrane region encompassing the entirety of the cell membrane and the intracellular kinase domain complete the RTK. Once a specific ligand binds to the extracellular portion of the receptor, the protein dimerizes and changes its structure, thus allowing the intracellular kinase domain to catalyze the addition of phosphate groups to the tyrosine residues in itself (autophosphorylation).

ATP is the primary source of phosphate. Once the protein dephosphorylates ATP and auto-phosphorylates the tyrosine residues residing in TK, the phosphotyrosines serve as docking sites for other proteins involved in signal transduction. This process is a series of complex biochemical processes that assist the cell in cell differentiation, regulation of cell growth, and cell death. The biochemical pathway is depicted in Figure 1. The crucial role tyrosine kinase proteins play in cell division has led oncologists to use the protein as a target site for targeted cancer therapy in an attempt to decrease uncontrolled cell division.[2]

Antineoplastic medications are infamous for causing an array of toxicities ranging from dermatological manifestations to cardiovascular side-effects. Physicians face the challenge of having to deal with unexpected complications when administering cancer therapy. The use of targeted cancer treatment, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, is increasing because it is more effective and less toxic to normal tissue. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis is an inflammation of the cornea caused by the inhibition of the wound healing and hydrating pathways.

The antineoplastic medications that commonly cause tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis are known as EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors; however, TKIs which affect the PDGFR, proto-onco B-Raf (BRAF), Janus kinase (JAK), and VEGFR pathways also make patients susceptible to TKI keratitis. The EGFR pathway regulates not only the proliferation of cells but also ocular tissue differentiation. Thus, its inhibition can cause decreased proliferation of malignant cells but may also lead to ocular toxicity. Due to the collaboration between multiple specialties providing the best possible care, ophthalmologists should be made aware of the complications seen in targeted cancer therapy patients and subsequently have the knowledge to treat them promptly. The literature is limited on the course of TKI keratitis; however, case studies show a good prognosis in most patients with only a few cases refractory to maximal treatment.[3][4][5]

This article will discuss the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of TKI keratitis and its complications.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

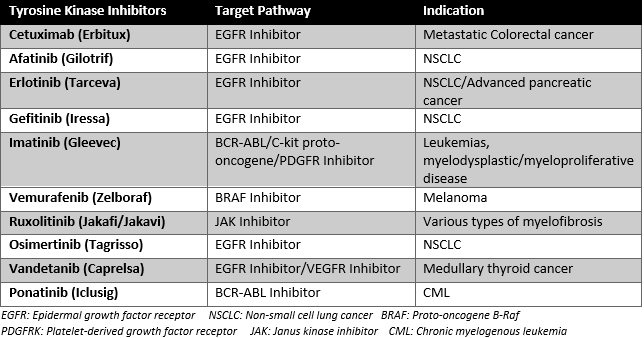

The most common drugs that cause tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis are the medications that inhibit the TKI receptor in the EGFR pathway, such as cetuximab, afatinib, erlotinib, and gefitinib. However, other TKIs are also known to cause TKI keratitis, such as imatinib, vemurafenib, ruxolitinib, osimertinib, vandetanib, and ponatinib, as seen in Figure 2.

Cetuximab is a TKI monoclonal antibody targeting the EGFR receptor, primarily used for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Reported toxicities consist of acneiform rash, nausea, electrolyte disorders, weakness, and malaise. The literature on the ocular toxicities of cetuximab is limited, with most complications recorded consisting of trichomegaly or abnormally long eyelashes, conjunctivitis, and blepharitis. There are isolated reports of patients experiencing keratitis while taking cetuximab as monotherapy.[6][7]

Afatinib is an oral EGFR TKI used as a first-line treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with unique EGFR mutations for either local or metastatic malignancy. The most common recorded complications of afatinib consist of dry eyes, ulcerative keratitis, blurred vision, photophobia, and conjunctivitis. The prevalence of keratitis in patients with this medication is 0.8%.[8]

Erlotinib is an EGFR TKI recently approved for the treatment of advanced NSCLC and a part of combination therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Erlotinib causes trichomegaly and a periorbital rash, while blepharitis, xerosis, and keratitis are rarer side effects.[9][10]

Gefitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is an oral medication that actively inhibits the epidermal growth factor receptor. The medication was approved as first-line treatment for patients diagnosed with NSCLC who had sensitizing EGFR mutations. The most common side effects are dry skin, diarrhea, and rash, which are reversible and typically mild. In some cases, patients were found to experience TKI keratitis and trichomegaly.[11]

Imatinib is an inhibitor of multiple TK proteins that functions as a treatment for many malignancies. It was shown to cause ulcerative keratitis in a study analyzing patients on dual treatment of imatinib and perifosine for refractory gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST).[12] Given perifosine has a history of causing keratitis along with many other ocular toxicities, it is unclear whether imatinib was the primary factor that led to the patients developing keratitis.[12]

Vemurafenib is a BRAF inhibitor that is primarily used as a treatment for melanoma. In a study analyzing the toxicities of vemurafenib, two patients out of 568 were found to develop keratitis, placing the incidence at 0.4%.[13]

Ruxolitinib is a JAK inhibitor used for various types of myelofibrosis pathologies. The literature is limited on the absolute number of cases of patients developing keratitis; however, a study analyzing Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis concluded that the JAK inhibitor made patients susceptible to fungal keratitis.[14]

Osimertinib is an EGFR-TKI that is the first-line treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC found to have an EGFR mutation. In a study done by Scott et al. [15], 0.7% of patients out of a total of 1142 were found to develop keratitis.[15]

Vandetanib is an EGFR TKI that is primarily used as a treatment for medullary thyroid cancer. Studies displaying the incidence of TKI keratitis are limited; however, it is hypothesized that vandetanib makes patients susceptible to keratitis due to the inhibition of the EGFR pathway.[16]

Ponatinib is a BCR-ABL inhibitor used as a treatment for CML. Studies reviewing the incidence of keratitis in patients taking ponatinib are limited. However, it is believed to cause many ocular toxicities, keratitis being one of them.[17]

Epidemiology

The tyrosine kinase inhibitors are usually prescribed for malignancies in patients where age is a non-modifiable risk factor. The majority of patients are diagnosed with cancers, such as NSCLC, at an older age. Patients diagnosed with tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis are over the age of 60, with no significant difference in gender or ethnicity. However, due to the rarity of this pathology, further studies should be done to determine the precise age at symptom presentation and diagnosis.[6][8][18][19][20]

Pathophysiology

Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) are part of a signaling pathway that plays a pivotal part in the progression of many cancers, such as squamous cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer. The receptor is also found in ectodermal ocular and periocular tissues consisting of the eyelid skin, lash follicles, meibomian glands, and the epithelial cells found in the conjunctiva and cornea. The ocular surface depends on the EGFR receptor to undergo epithelial cell proliferation, which assists in essential processes like wound healing. The EGFR acts as an optimal drug target to decrease the proliferation of malignant cells but also leads to ocular toxicity.[3][5]

EGFR-TKIs are hypothesized to result in corneal thinning and erosion due to the EGFR-mediated processes being affected. One of the initial steps in developing keratitis is the erosion of the epithelial cells in the corneal surface. The decreased proliferation in the epithelial cells results in decreased corneal surface hydration, impaired healing, and corneal inflammation. It is also hypothesized that given the EGFR cascade downregulates the growth cycle in hair follicles, the inhibition of this pathway leads to trichomegaly. The trichomegaly seen in these patients can worsen the inflammation through local mechanical irritation, further worsening the patient’s condition. Meibomian glands function to secrete meibum, a substance that protects the eye tear film layer by preventing evaporation. EGFR-TKI also prevents the proliferation of these glands, acting as another contributing factor to TKI keratitis.[3][5][21][22][23]

The JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib, is theorized to cause keratitis by impairing neutrophils from producing IL-17. IL-17 assists the cell in creating reactive oxygen species (ROS) for fungal killing. Without the ROS, patients become susceptible to fungal infections, which may lead to keratitis.[14]

The pathological mechanism for tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis in the specific PDGFR, BRAF, BRC-ABL, VEGFR, and c-kit protooncogene TKIs is unclear.

History and Physical

Patients who present with tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis may complain of photophobia, periocular pain, foreign body sensation, decreased visual acuity, or discrete redness.[4]

TKI keratitis is often mild and of varying manifestations when observed under slit-lamp examination. Filamentary keratitis consists of filamentous lesions that are adherent to the cornea. Diffuse punctate keratitis will have punctate lesions throughout the cornea.[6] Superficial punctate keratitis will have tiny lumps on the superficial cornea.[3][5][22][23][24]

Evaluation

Lissamine green dye and fluorescein 2% dye are routinely used to assess corneal surface changes as well as defects in the epithelium from keratitis. The dyes will stain any microscopic defects or erosions, allowing enhanced visualization during the slit-lamp examination.[4]

A patient with keratitis is evaluated using laboratory examinations to differentiate the causes of keratitis if a corneal ulcer or infiltrate is found on physical examination. Keratitis has many infectious etiologies such as bacteria, fungi, or viruses. Giemsa stain, gram stain, and PCR are used to rule out any infectious causes when a break in the epithelium is found.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis consists primarily of agents that promote surface hydration of the damaged cornea. Artificial tears (AT) and lubricants are commonly used. Topical corticosteroids can also be included in the treatment regimen to provide quick relief from discomfort by disrupting the inflammatory cycle. However, corticosteroid use is associated with increased intraocular pressure and glaucoma in susceptible individuals; therefore, a short course is generally advised. In severe cases of epithelial defects, bandage contact lenses may also be used. The contact lens acts to protect the cornea from injury as well as any shearing effects by the lids.[4][5](A1)

In a case study done by Johnson S. et al., a patient with a history of lung cancer was treated with erlotinib.[20] The patient developed recurrent keratitis due to a persisting epithelial defect. Despite the use of lubricating eye drops, anti-inflammatory therapy, and bandage contact lens, the epithelial defect remained unchanged. The patient’s keratitis resolved but recurred one month after resolution. Erlotinib was discontinued, and the epithelial defect was resolved within two weeks. If tolerated, the discontinuation of a TKI may assist in resolving the persistent ocular complications in patients refractory to the standard protocol of treatment.[20](B3)

The use of human epidermal growth factor (EGF) drops is a novel treatment for EGFR-TKI keratitis. In Kawakami’s report, a patient developed filamentous keratitis shortly after starting cetuximab for metastatic colorectal cancer.[24] Despite the patient being on standard therapy for one month, the keratitis persisted without relief of symptoms. The patient then consented for the use of EGF drops leading to a gradual diminishing of symptoms and complete resolution of the filamentous keratitis within three weeks. The patient did not have to discontinue the treatment with cetuximab.[24](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Before diagnosing tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis, other etiologies of keratitis should be taken into consideration. Microbiological tests such as a Gram stain and a Giemsa stain are routinely used to confirm the presence of either a bacterial or fungal organism in patients found to have a break in the epithelium. Viral keratitis is diagnosed clinically, but a PCR can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Infectious keratitis will commonly present with decreased vision, redness, pain, watering, and photophobia.

Bacterial keratitis (BK) has a strong association with contact lens wear. It is the most common etiology of infectious keratitis. Patients may have stromal melting, ground glass appearance infiltrates with well-defined borders and hypopyon. Patients with BK have ulcerations that progress rapidly compared to fungal or viral keratitis. This infectious etiology can be diagnosed clinically in 69% of cases, with gram staining often being done to confirm the diagnosis.[25][26][27]

Fungal keratitis (FK) incidence rates differ depending on geographical location. In temperate climates, FK makes up a marginal percentage of infectious keratitis cases. However, in tropical areas, FK consists of more than 50% of confirmed infectious keratitis cases.[28] Contact lens wear is a risk factor for developing this pathology. Ocular examination findings consist of a raised surface, satellite lesions, feathery margins, and infiltrates. Patients will often undergo an infectious disease workup to confirm the clinical suspicion. Correct diagnosis through clinical presentation alone is achieved in only 62% of cases.[25][26][28]

The most common type of viral keratitis (VK) is herpetic keratitis (HK). It can be recurrent and chronic. About half a million people in the U.S and 1.5 million around the world are diagnosed with HK.[29] The less common etiologies of viral keratitis are varicella-zoster virus and cytomegalovirus. On ocular examination, patients may have the classic finding of a dendritic ulcer and stromal keratitis. In cases of atypical presentation, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test is available.[25][29]

Prognosis

Patients who develop keratitis while on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy will most commonly experience a resolution of the keratitis when treated with the standard protocol of therapy used to rehydrate the cornea. In some cases, cessation of the TKI, bandage contact lens, or EGF eyedrops were used as alternative treatments. Most patients experience a resolution of symptoms with alternative treatment when refractory to the standard therapy.[6][8][24][30]

Complications

Even though the literature on tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis is limited, there have been isolated case studies of patients developing severe complications after being diagnosed with TKI keratitis, such as corneal perforation, secondary infection, and ulcerative keratitis. Bilateral ulcerative keratitis was seen in a patient on afatinib in a case study done by McKelvie et al.[8] The patient did not have any findings suggestive of microbial etiology. Due to the patient’s extensive keratitis and increased risk of perforation and secondary infection, afatinib cessation was urgently recommended, and treatment with a bandage contact lens, steroids, and antibiotics was started. With the aggressive treatment and cessation of the drug, the patient had resolution of the complications of epithelial defects bilaterally.[8]

In a more severe and isolated case reported by Sobol et al., a patient being treated with erlotinib was diagnosed with streptococcus dysgalactiae infectious keratitis, subsequently progressing to corneal perforation.[18] The patient became highly susceptible to not only keratitis but also epithelial defects. Regardless of the aggressive medical intervention, the patient progressed to endophthalmitis and orbital cellulitis. Visual acuity decreased progressively, and eventually, the eye was eviscerated.[18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis is rarely severe, with most patients experiencing mild keratitis. However, the possibility of severe consequences, such as complete visual loss, exists in a minority of patients. Patients who are currently taking a TKI should be advised to seek immediate medical assistance if they experience periocular pain, photophobia, decreased visual acuity, foreign body sensation, and/or discrete redness, as these are signs of possible ocular toxicity. Patients tend to have a good prognosis when the disease is diagnosed and treated promptly.

Pearls and Other Issues

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor keratitis is a complication of certain antineoplastic medications that target many pathways. The inhibition of the EGFR pathway disrupts the differentiation of many tissues, affecting the cornea by causing decreased corneal healing and proliferation. The inhibition of these two key processes leads to TKI keratitis.

Management in most cases of TKI keratitis consists of hydrating the cornea but can require more aggressive treatment. Prognosis is good in most patients.

Many types of keratitis should be kept in the differential when working-up a patient with ocular disturbances and taking a TKI. The ophthalmologist should be able to discern one type of keratitis from another based on the clinical presentation and laboratory exams.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Physicians, nurses, or technicians who are caring for patients under targeted cancer therapy should always ask the patient if they have experienced any changes in vision. TKI keratitis may be misdiagnosed or diagnosed late in the disease course. Any visual symptoms should lead to an ophthalmology consult.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Neet K, Hunter T. Vertebrate non-receptor protein-tyrosine kinase families. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 1996 Feb:1(2):147-69 [PubMed PMID: 9140060]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJiao Q, Bi L, Ren Y, Song S, Wang Q, Wang YS. Advances in studies of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and their acquired resistance. Molecular cancer. 2018 Feb 19:17(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0801-5. Epub 2018 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 29455664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHo WL, Wong H, Yau T. The ophthalmological complications of targeted agents in cancer therapy: what do we need to know as ophthalmologists? Acta ophthalmologica. 2013 Nov:91(7):604-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02518.x. Epub 2012 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 22970709]

Davis ME. Ocular Toxicity of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Oncology nursing forum. 2016 Mar:43(2):235-43. doi: 10.1188/16.ONF.235-243. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26906134]

Huillard O, Bakalian S, Levy C, Desjardins L, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Pop S, Sablin MP, Le Tourneau C. Ocular adverse events of molecularly targeted agents approved in solid tumours: a systematic review. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2014 Feb:50(3):638-48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.016. Epub 2013 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 24256808]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSpecenier P, Koppen C, Vermorken JB. Diffuse punctate keratitis in a patient treated with cetuximab as monotherapy. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2007 May:18(5):961-2 [PubMed PMID: 17442661]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFraunfelder FT, Fraunfelder FW. Trichomegaly and other external eye side effects associated with epidermal growth factor. Cutaneous and ocular toxicology. 2012 Sep:31(3):195-7. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2011.636118. Epub 2011 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 22122121]

McKelvie J, McLintock C, Elalfy M. Bilateral Ulcerative Keratitis Associated With Afatinib Treatment for Non-Small-cell Lung Carcinoma. Cornea. 2019 Mar:38(3):384-385. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001808. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30418275]

Lane K, Goldstein SM. Erlotinib-associated trichomegaly. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2007 Jan-Feb:23(1):65-6 [PubMed PMID: 17237698]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhou Z, Sambhav K, Chalam KV. Erlotinib-associated severe bilateral recalcitrant keratouveitis after corneal EDTA chelation. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2016 Dec:4():1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2016.06.003. Epub 2016 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 29503911]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRawluk J, Waller CF. Gefitinib. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 2018:211():235-246. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-91442-8_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30069771]

Hager T, Seitz B. Ocular side effects of biological agents in oncology: what should the clinician be aware of? OncoTargets and therapy. 2013 Dec 24:7():69-77. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S54606. Epub 2013 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 24391443]

Choe CH, McArthur GA, Caro I, Kempen JH, Amaravadi RK. Ocular toxicity in BRAF mutant cutaneous melanoma patients treated with vemurafenib. American journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Oct:158(4):831-837.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.07.003. Epub 2014 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 25036880]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTaylor PR, Roy S, Meszaros EC, Sun Y, Howell SJ, Malemud CJ, Pearlman E. JAK/STAT regulation of Aspergillus fumigatus corneal infections and IL-6/23-stimulated neutrophil, IL-17, elastase, and MMP9 activity. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2016 Jul:100(1):213-22. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A1015-483R. Epub 2016 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 27034404]

Scott LJ. Osimertinib as first-line therapy in advanced NSCLC: a profile of its use. Drugs & therapy perspectives : for rational drug selection and use. 2018:34(8):351-357. doi: 10.1007/s40267-018-0536-9. Epub 2018 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 30631243]

Bhatti MT, Salama AKS. Neuro-ophthalmic side effects of molecularly targeted cancer drugs. Eye (London, England). 2018 Feb:32(2):287-301. doi: 10.1038/eye.2017.222. Epub 2017 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 29052609]

Baker DE. Approvals, Submission, and Important Labeling Changes for US Marketed Pharmaceuticals. Hospital pharmacy. 2014 Mar:49(3):287-94. doi: 10.1310/hpj4903-287. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24715749]

Sobol EK, Ahmad S, Ibrahim K, Alfaro C, Pakett J, Esquenazi K, Della Rocca D, Ginsburg R. Rapidly progressive streptococcus dysgalactiae corneal ulceration associated with erlotinib use in stage IV lung cancer. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2020 Jun:18():100630. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100630. Epub 2020 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 32140616]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIbrahim E, Dean WH, Price N, Gomaa A, Ayre G, Guglani S, Sallam A. Perforating corneal ulceration in a patient with lung metastatic adenocarcinoma treated with gefitinib: a case report. Case reports in ophthalmological medicine. 2012:2012():379132. doi: 10.1155/2012/379132. Epub 2012 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 23320223]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson KS, Levin F, Chu DS. Persistent corneal epithelial defect associated with erlotinib treatment. Cornea. 2009 Jul:28(6):706-7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31818fdbc6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19512896]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakamura Y, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): role in corneal wound healing and homeostasis. Experimental eye research. 2001 May:72(5):511-7 [PubMed PMID: 11311043]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMelichar B, Nemcová I. Eye complications of cetuximab therapy. European journal of cancer care. 2007 Sep:16(5):439-43 [PubMed PMID: 17760931]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTonini G, Vincenzi B, Santini D, Olzi D, Lambiase A, Bonini S. Ocular toxicity related to cetuximab monotherapy in an advanced colorectal cancer patient. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005 Apr 20:97(8):606-7 [PubMed PMID: 15840884]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKawakami H, Sugioka K, Yonesaka K, Satoh T, Shimomura Y, Nakagawa K. Human epidermal growth factor eyedrops for cetuximab-related filamentary keratitis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Aug 10:29(23):e678-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0694. Epub 2011 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 21690478]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAustin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the Management of Infectious Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017 Nov:124(11):1678-1689. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.012. Epub 2017 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 28942073]

Jongkhajornpong P, Nimworaphan J, Lekhanont K, Chuckpaiwong V, Rattanasiri S. Predicting factors and prediction model for discriminating between fungal infection and bacterial infection in severe microbial keratitis. PloS one. 2019:14(3):e0214076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214076. Epub 2019 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 30893373]

Acharya M, Farooqui JH, Jain S, Mathur U. Pearls and paradigms in Infective Keratitis. Romanian journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Apr-Jun:63(2):119-127 [PubMed PMID: 31334389]

Thomas PA, Kaliamurthy J. Mycotic keratitis: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2013 Mar:19(3):210-20. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12126. Epub 2013 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 23398543]

Shah A, Joshi P, Bhusal B, Subedi P. Clinical Pattern And Visual Impairment Associated With Herpes Simplex Keratitis. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:13():2211-2215. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S219184. Epub 2019 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 31814705]

Yoshioka H, Hotta K, Kiura K, Takigawa N, Hayashi H, Harita S, Kuyama S, Segawa Y, Kamei H, Umemura S, Bessho A, Tabata M, Tanimoto M, Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group. A phase II trial of erlotinib monotherapy in pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer who do not possess active EGFR mutations: Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group trial 0705. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2010 Jan:5(1):99-104. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c20063. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19898258]