Introduction

Congenital heart disease is an abnormal formation of the heart or blood vessels next to the heart. It has an incidence of 8 cases of every 1000 live birth worldwide.[1] In the United States, congenital heart disease affects 1% of births (40,000) per year, of which 25% have critical Congenital heart disease.[2][3] In the U.S. the congenital heart disease represents approximately 4.5% of all neonatal deaths. The survival rate of patients with congenital heart disease will depend on the severity, time of diagnosis, and treatment. Approximately 97% of babies born with a non-critical congenital heart disease have a life expectancy of one year of age, and approximately 95% are expected to live around 18 years of age.

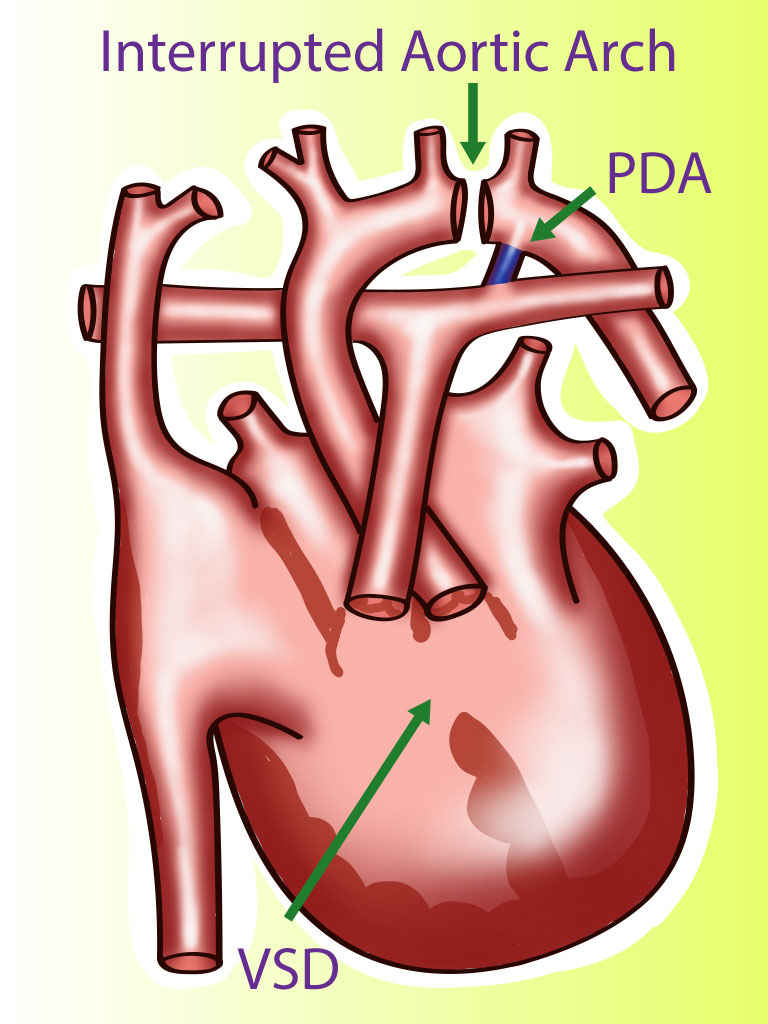

A rare type of congenital heart disease is an interrupted aortic arch (IAA), which affects approximately 1.5% of congenital heart disease patients.[4] Interrupted aortic arch is an anomaly that can be considered the most severe form of aortic coarctation.[5] In an IAA, there is an anatomical and luminal disruption between the ascending and descending aorta. IAA is a ductus dependent lesion since this is the only way the blood flow can travel to places distal to the disruption. There is posterior malalignment of the conal septum additional to the interrupted aortic arch, producing a ventricular septal defect as an associated lesion. This lesion is present is approximately 73% of all cases. Due to this malalignment, there could be left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Besides a ventricular septal defect, IAA can be associated with other more complicated cardiac anomalies; for example, transposition of the great arteries, truncus arteriosus, aortopulmonary window, single ventricle, aortic valve atresia, right-sided ductus, and double-outlet right ventricle.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Almost 50% of patients with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) have a 22q11.2 deletion; this cause of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome. Approximately 75% to 85% of patients with a 22q11.2 deletion have congenital heart disease that can range from asymptomatic to very severe that requires intervention in the newborn period. Besides an IAA, these patients can have other types of congenital heart diseases that can be classified into two groups, the branchial arch defects, and conotruncal defects. Branchial arch defects include IAA, coarctation of the aorta, and right aortic arch. Conotruncal defects include tetralogy of Fallot, sub-arterial ventricular septal defects, double-outlet right ventricle, and truncus arteriosus. Another syndrome associated with IAA is CHARGE syndrome.

Epidemiology

The incidence of interrupted aortic arch (IAA) is about 2 cases per 100,000 live births.

Nearly all patients with IAA present in the first 2 weeks of life when the ductus arteriosus closes. Most patients present in the first day of life.

Pathophysiology

During fetal circulation, the ductus arteriosus provides blood to the distal extremities of the fetus and the upper part of the body receives its blood supply from the left ventricle to the aorta. After birth, the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, promoting the closure of the ductus arteriosus. This leads to the inability of the heart to provide blood to the distal part of the body and produces respiratory distress and cyanosis, leading to cardiogenic shock and death if the necessary measures are not instated in time.

Classification

According to the Celoria and Patton classification, interrupted aortic arch can be grouped into three types, depending on the site of the disruption[6][7][8]:

- Type A: The disruption is located distal to the left subclavian artery; this is the second most common disruption represents approximately 13% of the cases.

- Type B: The disruption is located between the left carotid artery and the left subclavian artery; this is the most common anomaly, representing approximately 84% of the cases.

- Type C: The disruption is located between the innominate artery and the left carotid artery; this is a rare type represents approximately 3% of all cases.

These three types of IAA can be sub-classified according to the origin of the subclavian artery:

- Type 1: Normal origin of the subclavian artery.

- Type 2: Aberrant right subclavian artery, found distal to the left subclavian artery.

- Type 3: Isolated right subclavian artery; found originating from a right patent ductus arteriosus.

History and Physical

The baby may be asymptomatic until the ductus arteriosus closes and the patient develops tachypnea, feeding difficulties, respiratory distress, cyanosis, and anuria which, ultimately, can lead to shock and death. The physical exam will reveal absent pulses with a difference in blood pressure between the right arm and lower extremities. Sometimes, there may be an oxygen discrepancy between the left and right side of the body.

Evaluation

When the diagnosis is suspected, it is imperative as initial work up to perform a blood gas, chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram. The blood gas will reveal metabolic acidosis. The chest radiograph will show cardiomegaly and increased pulmonary markings. The electrocardiogram, typically, has nonspecific findings which include biventricular hypertrophy or right ventricular predominance. The echocardiogram will define the site of the disruption. Other imaging modalities used for the diagnosis of this entity are cardiac angiography, computed tomography angiography of the chest, and magnetic resonance angiography. These modalities are used to get a more comprehensive understanding of the lesion’s anatomy before surgical repair.[9][10][5]

In addition to the imaging studies, all patients should have a fluorescence in situ hybridization since there is a high association with chromosome 22q11 deletion, which is associated with DiGeorge syndrome. Serum calcium may be low in patients with DiGeorge syndrome.[11][4]

Treatment / Management

Prostaglandin E1 is necessary to start early to avoid sudden cardiac collapse and death.[1] The role of the prostaglandins is to maintain the patency of the ductus arteriosus, thus guaranteeing the perfusion of the lower part of the body until surgical correction is done. In the presence of shock, the patient should be managed with inotrope support, and treatment should be adjusted depending on the clinical response of the patient.

Once diagnosed, the treatment is immediate surgery. The objective of the surgery is to form unobstructed continuity between the ascending and descending aorta and to repair associated defects with the most common atrial and/or ventricular septum defect. The repair is done using either native arterial tissue, a homograph, or autograph vascular patch. For ventricular septal defect, repairs are closed with a synthetic patch. This synthetic patch is made up of polyester or polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). An alternative route to a definitive single-operation repair of the arch is to implement a two-stage approach. This approach consists of the reconstruction and placement of a pulmonary artery band in stage 1, postponing the placement of the ventricular septal defect closure to a later time. For the second stage procedure of the procedure, the pulmonary band is removed.[12]

In cases of significant outflow tract obstruction, it may be necessary to perform a complex combination of the Norwood and Rastelli procedures.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

- Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

- Bicuspid aortic valve

- Coarctation of the aorta

- DiGeorge syndrome

- Neonatal sepsis

- Patent Ductus Arteriosis (PDA)

- Transportation of the great vessels

- Truncus Arteriosis

- Velocardiofacial syndrome

- Ventral septal defect

Pearls and Other Issues

Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) is a ductus dependent lesion; this is the reason is imperative to diagnose and start prostaglandin E1 as soon as possible. DiGeorge syndrome is the most common syndrome associated with this congenital heart disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of interrupted aortic arch is with an interprofessional team that consists of a pediatrician, pediatric cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, radiologist and an internist. IAA is a relatively rare disorder which is often associated with other heart defects.

Once diagnosed, the treatment is immediate surgery. The objective of the surgery is to form unobstructed continuity between the ascending and descending aorta and to repair associated defects with the most common atrial and/or ventricular septum defect. The repair is done using either native arterial tissue, a homograph, or autograph vascular patch. For ventricular septal defect, repairs are closed with a synthetic patch. This synthetic patch is made up of polyester or polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). An alternative route to a definitive single-operation repair of the arch is to implement a two-stage approach. This approach consists of the reconstruction and placement of a pulmonary artery band in stage 1, postponing the placement of the ventricular septal defect closure to a later time. For the second stage procedure of the procedure, the pulmonary band is removed.[12]

In cases of significant outflow tract obstruction, it may be necessary to perform a complex combination of the Norwood and Rastelli procedures.[12] The prognosis of these infants is dependent on birth weight, associated heart defects and time of surgery. The outlook for most infants is guarded and multiple heart surgeries are often needed. (Level V)

Media

References

Hu XJ, Ma XJ, Zhao QM, Yan WL, Ge XL, Jia B, Liu F, Wu L, Ye M, Liang XC, Zhang J, Gao Y, Zhai XW, Huang GY. Pulse Oximetry and Auscultation for Congenital Heart Disease Detection. Pediatrics. 2017 Oct:140(4):. pii: e20171154. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1154. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28939700]

Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002 Jun 19:39(12):1890-900 [PubMed PMID: 12084585]

Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, Correa A. Prevalence of congenital heart defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998-2005. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008 Dec:153(6):807-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.059. Epub 2008 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 18657826]

Varghese R, Saheed SB, Omoregbee B, Ninan B, Pavithran S, Kothandam S. Surgical Repair of Interrupted Aortic Arch and Interrupted Pulmonary Artery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2015 Dec:100(6):e139-40. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.064. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26652572]

Patel DM, Maldjian PD, Lovoulos C. Interrupted aortic arch with post-interruption aneurysm and bicuspid aortic valve in an adult: a case report and literature review. Radiology case reports. 2015 Oct:10(3):5-8. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2015.06.001. Epub 2015 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 26649108]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchreiber C, Mazzitelli D, Haehnel JC, Lorenz HP, Meisner H. The interrupted aortic arch: an overview after 20 years of surgical treatment. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 1997 Sep:12(3):466-9; discussion 469-70 [PubMed PMID: 9332928]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSato S, Akagi N, Uka M, Kato K, Okumura Y, Kanazawa S. Interruption of the aortic arch: diagnosis with multidetector computed tomography. Japanese journal of radiology. 2011 Jan:29(1):46-50. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0517-y. Epub 2011 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 21264661]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMendoza Díaz PM, Herrera Gomar M, Rojano Castillo J. Interrupted Aortic Arch in an Adult and Myocardial Infarction. Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.). 2016 Feb:69(2):212. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2015.06.019. Epub 2015 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 26385081]

Dillman JR, Yarram SG, D'Amico AR, Hernandez RJ. Interrupted aortic arch: spectrum of MRI findings. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2008 Jun:190(6):1467-74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3408. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18492893]

Serraf A, Lacour-Gayet F, Robotin M, Bruniaux J, Sousa-Uva M, Roussin R, Planché C. Repair of interrupted aortic arch: a ten-year experience. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1996 Nov:112(5):1150-60 [PubMed PMID: 8911311]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). Medicine. 2011 Jan:90(1):1-18. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182060469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21200182]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlsoufi B, Schlosser B, McCracken C, Sachdeva R, Kogon B, Border W, Mahle WT, Kanter K. Selective management strategy of interrupted aortic arch mitigates left ventricular outflow tract obstruction risk. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Feb:151(2):412-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.09.060. Epub 2015 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 26520007]