Introduction

Pregnancy triggers numerous physiological changes, including volume expansion, vasodilation, and changes in hormonal milieu, which are crucial in facilitating the kidneys' adaption to pregnancy. These changes cause a decline in serum creatinine levels, which is most prominent in the second trimester, after which serum creatinine begins to stabilize. Glomerulonephritis during pregnancy may present as acute kidney injury (AKI) or exacerbate preexisting chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD can affect both maternal and fetal well-being, but data on glomerulonephritis in pregnancy remain limited. Unique kidney-related pathophysiological changes in pregnancy are explored, with a focus on the evaluation and management of glomerulonephritis in this context.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The causes of glomerular diseases in pregnancy are similar to those in the general population. Etiologies of glomerulonephritis in pregnancy include focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy (IgAN), membranous nephropathy, lupus nephritis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV), and Goodpasture syndrome (anti-glomerular basement membrane disease).

Please see the following StatPearls' companion resources for further information:

Epidemiology

Approximately 3% of pregnant women show laboratory evidence of CKD.[1] However, data on glomerular diseases in pregnancy are limited, making the exact incidence and prevalence unclear.

Pathophysiology

Normal physiological changes in pregnancy include an increase in renal plasma flow by up to 80%, a 50% rise in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and dilation of the pelvicalyceal system.[2] Plasma volume expands by 40% to 50%, and the osmostat resets, leading to a 4 to 5 mmol/L decrease in serum sodium. This reset may be linked to the production of human chorionic gonadotropin.[3]

Despite normoglycemia, proteinuria and glucosuria are expected during pregnancy. These changes contribute to lower serum creatinine levels. Common equations for estimating GFR may underestimate kidney dysfunction, as they do not account for pregnancy-related hyperfiltration. The reference limit for proteinuria in pregnancy is 300 mg/24 hours or a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) of 0.3 mg/mg, compared to 0.15 mg/mg in healthy non-pregnant individuals.[4] Normal serum creatinine levels in pregnancy range between 0.4 and 0.6 mg/dL, varying with muscle mass.[5]

Histopathology

For a detailed discussion of the histological findings for each clinical condition, please refer to the StatPearls' companion resources links mentioned in the Etiology section.

History and Physical

Glomerular diseases can have an insidious onset, and physical symptoms may not become apparent until the disease has progressed significantly. Symptoms may include hematuria, edema, frothy urine, hypertension, and, in acute cases, oliguria. Signs and symptoms of glomerular diseases are typically categorized into 2 broad groups—nephrotic syndrome and nephritic syndrome.

Nephrotic syndrome is characterized by edema, hypoalbuminemia (<3.5 g/dL), hyperlipidemia, and proteinuria exceeding 3.5 g/d. Nephritic syndrome presents with hematuria, mild proteinuria, hypertension, dysmorphic red blood cells in the urine, red cell casts, and edema. Preeclampsia can present with similar symptoms and must be ruled out before starting immunosuppressive therapy.

Evaluation

Glomerulonephritis in pregnancy may present as de novo AKI detected through routine blood tests or as a progression of underlying CKD. As noted above, current formulas used to estimate GFR do not account for the physiological changes of pregnancy. While some authors recommend obtaining a 24-hour urine creatinine to calculate creatinine clearance, this approach can be particularly cumbersome for pregnant patients.[6] Some studies recommend using the 75th percentile of prepregnancy creatinine levels as a threshold to define impaired kidney function during pregnancy.[6][7] A standard protocol, proposed by Maria et al, suggests using a creatinine range of 0.4 to 0.6 mg/dL as the cutoff for normal kidney function in pregnancy.[5]

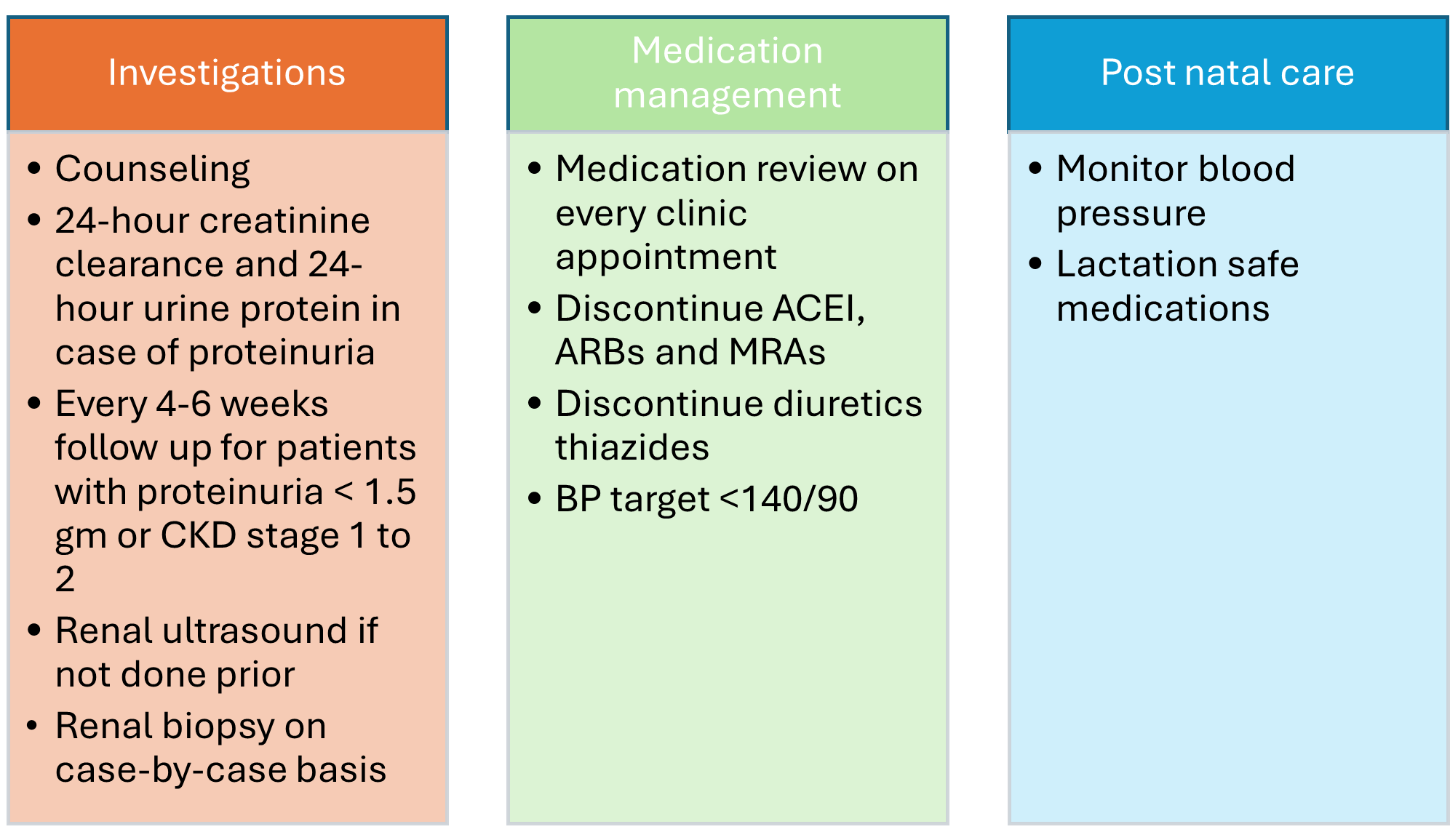

A UPCR of 0.3 g/g or higher is considered abnormal in pregnancy. Nephrology consultation is recommended for all suspected cases of glomerulonephritis in pregnancy and for patients with a history of the condition, regardless of current disease activity. The optimal frequency and selection of routine blood tests vary across studies.[8][9] Regular outpatient follow-up every 4 to 6 weeks is essential, including monitoring with a basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, UPCR, and serum levels of sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, urea, and creatinine (see Image. Overview of Glomerulonephritis Management During Pregnancy). A kidney ultrasound is also recommended if not previously obtained.

Additional tests, including antinuclear antibody (ANA), ANCA, complement levels (C3 and C4), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, and anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibody (anti-PLA2R), should be ordered for new-onset proteinuria. Each visit should include blood pressure monitoring and a review of home readings for at-risk patients, such as those with a history of preeclampsia or uncontrolled hypertension. Medications should also be reviewed at every visit.

Counseling is essential, as glomerulonephritis presents unique risks and challenges during pregnancy. Pregnancy should be delayed for at least 6 months after remission begins. Patients with active glomerular disease or CKD face an increased risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) neonates, and preeclampsia.[10][11][12] Prepregnancy counseling is critical, as many immunosuppressive medications are teratogenic and must be discontinued before conception.

For all pregnant patients with new or preexisting glomerulonephritis, counseling should cover the following:

- An overview of pregnancy outcomes specific to the underlying glomerulonephritis.

- Risks of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

- Potential adverse effects of medications prescribed for glomerulonephritis.

- Risks associated with kidney biopsy, if deemed necessary.

A kidney biopsy is indicated in cases of worsening existing glomerular disease when biopsy findings could alter management or if there is suspicion of significant de novo glomerular disease that may require treatment. The risk of complications from a kidney biopsy is increased during pregnancy, particularly after 20 to 25 weeks, when the risk of bleeding is doubled compared to before 20 weeks.[13][14]

Indications for biopsy include:

- A rapid decline in estimated GFR (eGFR) without a diagnosed cause or suspected worsening of underlying glomerulonephritis.

- Agreement between the patient and physician that immunosuppression may be necessary to prolong the pregnancy to 32 weeks.

- The detection of new-onset nephrotic syndrome before fetal viability (24 weeks of gestation), as obtaining a diagnosis can facilitate effective management.

Treatment / Management

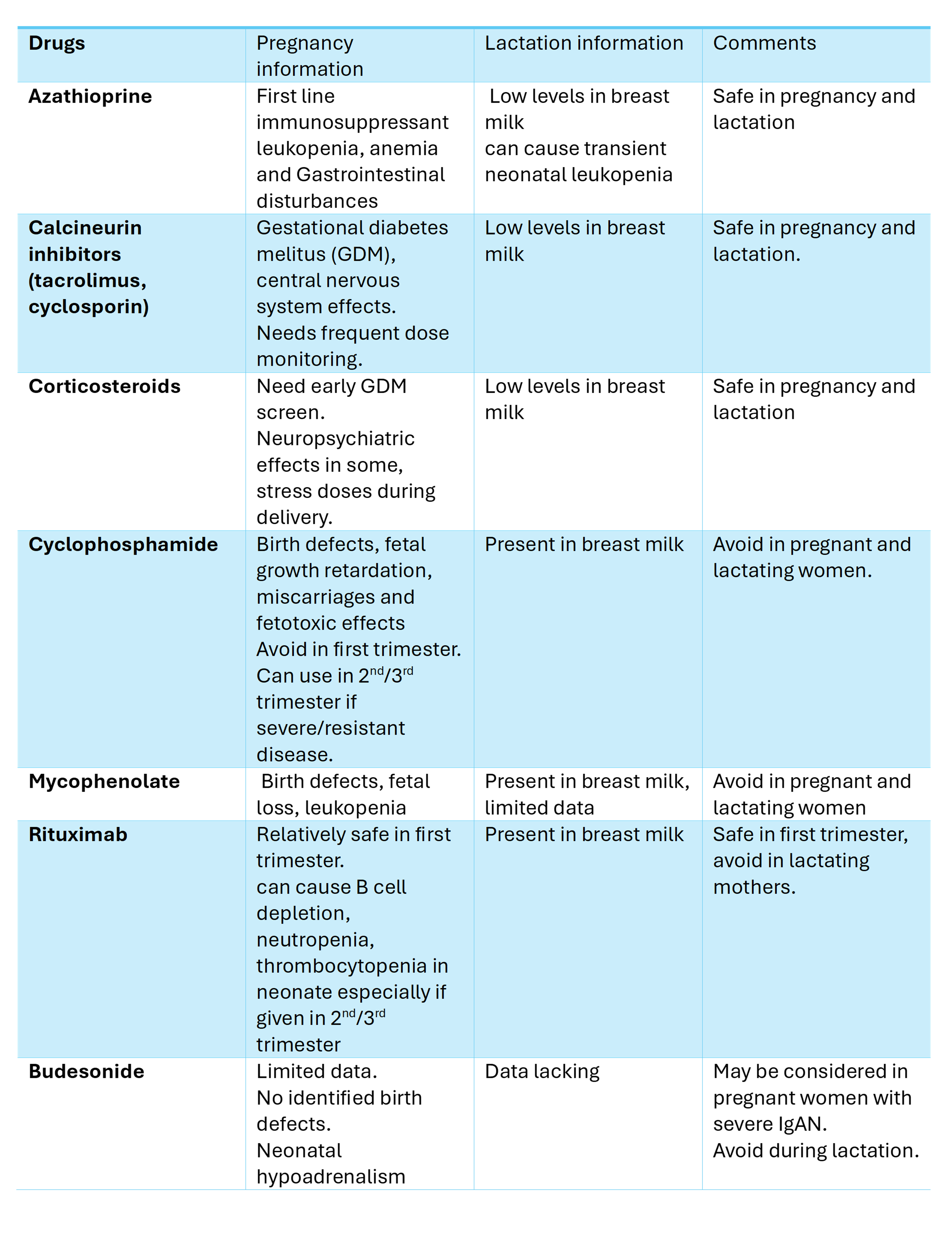

For patients with glomerulonephritis planning pregnancy, achieving disease remission on either no immunosuppression or pregnancy-safe immunosuppression for 3 to 6 months before conception is recommended. Remission criteria include stable GFR, inactive urine sediment, and proteinuria below 0.5 g/d (via 24-hour collection or spot UPCR). Although some immunosuppressive medications such as azathioprine and tacrolimus have been reported to be relatively safe during pregnancy, rare adverse effects and maternal-fetal complications have been reported with all immunosuppressants, regardless of the agent used. Shared decision-making is essential, involving a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of immunosuppression with the patient (see Image. Immunosuppressants in Pregnancy and Lactation).

Optimizing comorbid conditions such as hypertension and diabetes is essential in managing glomerulonephritis during pregnancy. First-line treatments for hypertension include beta-blockers (eg, labetalol) and calcium channel blockers (eg, nifedipine), with hydralazine as a second-line option. Aspirin prophylaxis, starting at 12 weeks of gestation, is recommended to reduce the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant patients with glomerulonephritis.[15] In pregnant patients with severe proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia (<2 g/dL), the risk of thromboembolism rises significantly, warranting prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin during pregnancy.[5][16](B3)

The literature suggests that FSGS seems to be the most prevalent glomerulonephritis in pregnancy, followed by IgAN, ANCA-related glomerulonephritis, and lupus nephritis.[17][18]

Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

Pregnant patients with known FSGS are at higher risk for complications such as preeclampsia and preterm delivery. Notably, FSGS is a common histopathological finding in preeclampsia. The timing of proteinuria onset, along with coexisting hypertension, can help differentiate preeclampsia-related FSGS from isolated FSGS. Laboratory markers, such as the soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase receptor 1 (sFlt-1)/placental growth factor (PlGF) ratio, can also aid in identifying preeclampsia.[19] A study reported an 11% risk of fetal loss and a 10% risk of premature delivery in patients with FSGS.[20] Oral steroids with a gradual taper are typically used during pregnancy unless contraindicated, such as in cases of uncontrolled diabetes. For steroid-resistant cases, calcineurin inhibitors may be considered, although the risks, including gestational diabetes, should be discussed with the patient. Case reports suggest that the collapsing variant of FSGS in pregnant patients has shown a favorable response to treatment.[21] (B3)

IgA Nephropathy

IgAN may present with microscopic or macroscopic hematuria, asymptomatic hematuria with proteinuria, or, in rare cases, AKI. IgAN is associated with higher risks of adverse fetal-maternal outcomes, including preeclampsia, SGA neonates, preterm birth, and cesarean delivery.[5] A large meta-analysis found that pregnant patients with preserved renal function did not experience significant renal function loss but had higher rates of preeclampsia, low birth weight neonates, preterm delivery, and infant loss.[22] In addition, studies indicate that pregnant patients with IgAN and stage 3 or higher CKD are at risk for rapid GFR decline.[23][24](A1)

Careful monitoring is appropriate for patients with mild, stable disease. Women with IgAN at stage 3 or higher should be informed about the risk of CKD progression and monitored closely. For those with progressive disease or rapidly advancing glomerulonephritis (crescentic IgAN) requiring treatment, corticosteroid pulse doses with taper may be used. Newer drugs, such as enteric-coated budesonide and sparsentan, have received approval for IgAN from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but they have not been tested in pregnancy, and sparsentan is contraindicated in pregnant patients. Budesonide may be used in select cases, but potential risks, such as hypoadrenalism in infants, should be discussed. Case reports have noted the use of tacrolimus for treating IgAN during pregnancy.[25] However, conclusively, corticosteroids remain the primary treatment for IgAN in pregnant patients.

Membranous Nephropathy

Literature on membranous nephropathy is limited. Similar to other causes of nephrotic syndrome, membranous nephropathy is associated with adverse fetal and maternal outcomes. When phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) antibodies are present along with the typical nephrotic syndrome presentation, a kidney biopsy is unnecessary for diagnosing primary membranous nephropathy. However, secondary membranous nephropathy must be excluded through appropriate screening and serological workup. The role of PLA2R antibodies as predictors of adverse outcomes remains unclear.

Patients with proteinuria less than 3.5 g/dL, serum albumin greater than 3.0 g/dL, and eGFR above 60 mL/min/1.73 m² can be safely monitored without immunosuppression. For those experiencing AKI or worsening proteinuria, treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and rituximab (only during the first trimester). Case reports have demonstrated positive outcomes with tacrolimus treatment throughout pregnancy.[26][27] Additionally, thromboembolism prophylaxis with enoxaparin should be considered for pregnant patients, particularly if serum albumin is below 2.5 g/dL.(B2)

Lupus Nephritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) predominantly affects women of childbearing age, with approximately one-third of these women developing lupus nephritis.[28] Ideally, pregnancy should be considered only after a minimum of 6 months of disease quiescence. Teratogenic medications, such as mycophenolic acid analogs, should be discontinued, allowing for an adequate wash-out period of at least 6 to 8 weeks before conception.[29] Maternal complications in women with SLE include an earlier onset of preeclampsia, lupus flares, and preterm delivery. Fetal complications may involve abortions, stillbirths, and intrauterine growth restriction. One study reported adverse pregnancy outcomes in 19% of pregnancies, with fetal death occurring in 4%, preterm delivery in 9%, and SGA neonates in 10% of patients. The presence of lupus anticoagulants, use of antihypertensive medications, and low platelet counts have been associated with adverse outcomes. Additionally, maternal flares, higher disease activity, and increases in complement C3 levels further elevate fetal-maternal risk.[29](B3)

Pregnant patients with SLE should be screened for anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies because of the risk of complete congenital heart block in the neonate. Additionally, screening for antiphospholipid antibodies should be performed early in pregnancy due to an increased risk of fetal loss.[5] Kidney biopsy during pregnancy is indicated for worsening proteinuria, AKI with active urinary sediment, or suspicion of concurrent conditions such as thrombotic microangiopathy. If de novo lupus nephritis is diagnosed during pregnancy, the goal of induction and maintenance therapy should be to support the continuation of the pregnancy until the fetus matures as much as possible. Treatment options for lupus nephritis include glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and cyclosporine), and azathioprine, along with rituximab in the first trimester. Notably, it is advisable to continue hydroxychloroquine during pregnancy to reduce the risk of complications. Additionally, low-dose aspirin should be initiated before 16 weeks of gestation.[30][31] (A1)

Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis

AAV is rare in individuals of reproductive age and encompasses granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Associated adverse fetal and maternal outcomes include a preterm birth rate of 20% to 50%, intrauterine growth restriction in 20% of cases, cesarean section delivery in 25%, and hypertension affecting 21% of patients.[32][33] Before conception, the patient should be in remission while receiving a pregnancy-compatible medication. Glucocorticoids are considered a relatively safe treatment option for AAV during pregnancy.(A1)

Managing de novo AAV during pregnancy can be complex and challenging. Rituximab and corticosteroids may be used to induce remission. Plasma exchange should be considered for patients with rapidly declining GFR or those experiencing life- or organ-threatening manifestations.[34] In such cases, it is essential to discuss the risks and benefits of continuing the pregnancy with the patient. The safety of plasma exchange is comparable to that of the general population, provided there is no maternal hypotension.[35] Medications considered relatively safe during pregnancy include azathioprine, corticosteroids, and rituximab during the first trimester for maintenance therapy. However, newer agents such as avacopan and mepolizumab should be avoided during pregnancy due to insufficient data on their safety.(A1)

Anti-Glomerular Basement Membrane Glomerulonephritis

Anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis typically presents as rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, with or without pulmonary hemorrhage. There are limited case reports of this condition occurring during pregnancy, most of which involved patients requiring dialysis.[36][37] If anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis is suspected, a kidney biopsy should be performed to establish a definitive diagnosis. Treatment options include plasmapheresis, glucocorticoids, and rituximab, with no maintenance therapy necessary. (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

When assessing glomerular diseases in pregnancy, it is crucial to differentiate them from pregnancy-related conditions that present with overlapping features.

- Preeclampsia: This condition presents with hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation. Preeclampsia can lead to AKI, hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia, while urine sediment is typically bland. Eclampsia is characterized by the onset of seizures or coma during pregnancy or the postpartum period.

- HELLP syndrome: HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome can be a severe form of preeclampsia, resulting in multiorgan failure and coagulopathy.

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: This condition occurs in the third trimester, primarily affecting susceptible individuals. Clinical features include fever, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, hypertension, transaminitis, and encephalopathy. Laboratory findings may reveal hypoglycemia, coagulopathy, and elevated liver enzymes. Isolated renal involvement is uncommon in acute fatty liver of pregnancy.

- Thrombotic microangiopathy: Pregnancy-associated thrombotic microangiopathy is characterized by the presence of platelet and fibrin thrombi in the microcirculation, along with thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and renal and neurologic dysfunction. Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is more commonly observed in the postpartum period, while thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) often occurs during the second or third trimester. A kidney biopsy may be necessary to differentiate HUS/TTP from HELLP syndrome, although it poses risks in the presence of thrombocytopenia. Nonetheless, a kidney biopsy can provide valuable insights to guide treatment options, including plasma exchange or administration of eculizumab.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Rituximab is generally considered safe during the first trimester of pregnancy due to its IgG1 component, as placental transfer is not believed to occur until around the 16th week of gestation. Rituximab has a half-life of approximately 18 to 22 days and is typically eliminated within 3 to 4 months after the last dose. Because it can deplete B cells, if the drug is needed during the later stages of pregnancy, neonatal B-cell counts should be closely monitored until the infant is 6 months old.[38]

Tacrolimus is considered safe during pregnancy, and maintaining therapeutic levels is essential to reduce the risk of preterm births.[39][40] Monitoring renal function and potassium levels in neonates exposed to tacrolimus has also been recommended.[41] Similarly, cyclosporine is regarded as relatively safe for use during pregnancy.[42][43]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Pregnancy in patients with glomerulonephritis poses significant challenges and can be a source of anxiety for both patients and healthcare providers. The lack of comprehensive data and the limited availability of medications safe for use during pregnancy further complicate decision-making. Patients should receive education about their treatment options, potential complications, and expected pregnancy outcomes. Optimal management requires interdisciplinary coordination among gynecologists, rheumatologists, nephrologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, and neonatologists.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Glomerulonephritis during pregnancy poses significant challenges for both patients and the healthcare team. Ethical concerns prevent the inclusion of pregnant patients in clinical trials, resulting in a lack of evidence-based guidelines. Effective management hinges on shared decision-making and collaboration among primary care physicians, nephrologists, gynecologists, rheumatologists, and specialists in high-risk maternal-fetal medicine to ensure patient-centered care.

Ethical considerations are crucial in determining treatment options while respecting patient autonomy in decision-making. Clearly defining responsibilities within the interprofessional healthcare team allows each member to contribute their specialized knowledge and skills to optimize patient care. Effective communication among healthcare team members fosters a collaborative environment where information is shared, questions are welcomed, and concerns are promptly addressed.

Care coordination is essential for providing seamless and efficient patient care. Physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals must collaborate to streamline the patient’s journey from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up. This coordinated approach minimizes errors, reduces delays, and enhances patient safety, ultimately improving outcomes and delivering patient-centered care that prioritizes the well-being and satisfaction of pregnant patients with glomerulonephritis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Munkhaugen J, Lydersen S, Romundstad PR, Widerøe TE, Vikse BE, Hallan S. Kidney function and future risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study from HUNT II, Norway. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2009 Dec:24(12):3744-50. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp320. Epub 2009 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 19578097]

Cheung KL, Lafayette RA. Renal physiology of pregnancy. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2013 May:20(3):209-14. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.01.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23928384]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFeder J, Gomez JM, Serra-Aguirre F, Musso CG. Reset Osmostat: Facts and Controversies. Indian journal of nephrology. 2019 Jul-Aug:29(4):232-234. doi: 10.4103/ijn.IJN_307_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31423055]

Fishel Bartal M, Lindheimer MD, Sibai BM. Proteinuria during pregnancy: definition, pathophysiology, methodology, and clinical significance. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2022 Feb:226(2S):S819-S834. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.108. Epub 2020 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 32882208]

Gonzalez Suarez ML, Kattah A, Grande JP, Garovic V. Renal Disorders in Pregnancy: Core Curriculum 2019. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2019 Jan:73(1):119-130. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.006. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30122546]

Gao M, Vilayur E, Ferreira D, Nanra R, Hawkins J. Estimating the glomerular filtration rate in pregnancy: The evaluation of the Nanra and CKD-EPI serum creatinine-based equations. Obstetric medicine. 2021 Mar:14(1):31-34. doi: 10.1177/1753495X20904177. Epub 2020 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 33995570]

Wiles K, Bramham K, Seed PT, Nelson-Piercy C, Lightstone L, Chappell LC. Serum Creatinine in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Kidney international reports. 2019 Mar:4(3):408-419. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.10.015. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30899868]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCabiddu G, Castellino S, Gernone G, Santoro D, Giacchino F, Credendino O, Daidone G, Gregorini G, Moroni G, Attini R, Minelli F, Manisco G, Todros T, Piccoli GB, Kidney and Pregnancy Study Group of Italian Society of Nephrology. Best practices on pregnancy on dialysis: the Italian Study Group on Kidney and Pregnancy. Journal of nephrology. 2015 Jun:28(3):279-88. doi: 10.1007/s40620-015-0191-3. Epub 2015 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 25966799]

Blom K, Odutayo A, Bramham K, Hladunewich MA. Pregnancy and Glomerular Disease: A Systematic Review of the Literature with Management Guidelines. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2017 Nov 7:12(11):1862-1872. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00130117. Epub 2017 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 28522651]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHladunewich MA. Chronic Kidney Disease and Pregnancy. Seminars in nephrology. 2017 Jul:37(4):337-346. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2017.05.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28711072]

Al Khalaf S, Bodunde E, Maher GM, O'Reilly ÉJ, McCarthy FP, O'Shaughnessy MM, O'Neill SM, Khashan AS. Chronic kidney disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2022 May:226(5):656-670.e32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.10.037. Epub 2021 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 34736915]

Jeyaraman D, Walters B, Bramham K, Fish R, Lambie M, Wu P. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2024 Sep:131(10):1331-1340. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17807. Epub 2024 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 38488268]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoroni G, Calatroni M, Donato B, Ponticelli C. Kidney Biopsy in Pregnant Women with Glomerular Diseases: Focus on Lupus Nephritis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Feb 24:12(5):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12051834. Epub 2023 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 36902621]

Luciano RL, Moeckel GW. Update on the Native Kidney Biopsy: Core Curriculum 2019. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2019 Mar:73(3):404-415. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.011. Epub 2019 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 30661724]

. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 743: Low-Dose Aspirin Use During Pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jul:132(1):e44-e52. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002708. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29939940]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGleeson S, Lightstone L. Glomerular Disease and Pregnancy. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2020 Nov:27(6):469-476. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2020.08.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33328063]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVikse BE, Hallan S, Bostad L, Leivestad T, Iversen BM. Previous preeclampsia and risk for progression of biopsy-verified kidney disease to end-stage renal disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2010 Oct:25(10):3289-96. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq169. Epub 2010 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 20348149]

De Castro I, Easterling TR, Bansal N, Jefferson JA. Nephrotic syndrome in pregnancy poses risks with both maternal and fetal complications. Kidney international. 2017 Jun:91(6):1464-1472. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.019. Epub 2017 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 28233609]

Siligato R, Gembillo G, Cernaro V, Torre F, Salvo A, Granese R, Santoro D. Maternal and Fetal Outcomes of Pregnancy in Nephrotic Syndrome Due to Primary Glomerulonephritis. Frontiers in medicine. 2020:7():563094. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.563094. Epub 2020 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 33363180]

O'Shaughnessy MM, Jobson MA, Sims K, Liberty AL, Nachman PH, Pendergraft WF. Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients with Glomerular Disease Attending a Single Academic Center in North Carolina. American journal of nephrology. 2017:45(5):442-451. doi: 10.1159/000471894. Epub 2017 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 28445873]

Orozco Guillén OA, Velazquez Silva RI, Gonzalez BM, Becerra Gamba T, Gutiérrez Marín A, Paredes NR, Cardona Pérez JA, Soto Abraham V, Piccoli GB, Madero M. Collapsing Lesions and Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis in Pregnancy: A Report of 3 Cases. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2019 Dec:74(6):837-843. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.04.026. Epub 2019 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 31378644]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu Y, Ma X, Zheng J, Liu X, Yan T. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Kidney and Pregnancy Outcomes in IgA Nephropathy. American journal of nephrology. 2016:44(3):187-93. doi: 10.1159/000446354. Epub 2016 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 27578454]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSu X, Lv J, Liu Y, Wang J, Ma X, Shi S, Liu L, Zhang H. Pregnancy and Kidney Outcomes in Patients With IgA Nephropathy: A Cohort Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2017 Aug:70(2):262-269. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.01.043. Epub 2017 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 28320554]

Wang F, Lu JD, Zhu Y, Wang TT, Xue J. Renal Outcomes of Pregnant Patients with Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American journal of nephrology. 2019:49(3):214-224. doi: 10.1159/000496410. Epub 2019 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 30808834]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOrozco Guillén A, Soto Abraham V, Moguel Gonzalez B, Piccoli GB, Madero M. Podocytopathy Associated with IgA Nephropathy in Pregnancy: A Challenging Association. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Feb 27:12(5):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12051888. Epub 2023 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 36902674]

Saleem M, Iftikhar H. Anti-phospholipase A2 Receptor Antibody-Negative Membranous Nephropathy in Pregnancy. Cureus. 2023 Aug:15(8):e42827. doi: 10.7759/cureus.42827. Epub 2023 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 37664313]

Qin C, Hu Z, Shi Y, Cui H, Li J. Two successful pregnancies in a membranous nephropathy patient: Case report and literature review. Medicine. 2024 Feb 9:103(6):e37111. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037111. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38335417]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee JE, Mendel A, Askanase A, Bae SC, Buyon JP, Clarke AE, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Fortin PR, Gladman DD, Ramsey-Goldman R, Hanly JG, Inanç M, Isenberg DA, Mak A, Mosca M, Petri M, Rahman A, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Urowitz M, Wallace DJ, Bernatsky S, Vinet É. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Women with Lupus Nephritis in Pregnancy Therapeutic Challenge (SWITCH): The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics experience. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2023 Nov:82(11):1496-1497. doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224197. Epub 2023 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 37208152]

Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM, Laskin CA, Petri M, Lockshin MD, Sammaritano L, Branch DW, Porter TF, Sawitzke A, Merrill JT, Stephenson MD, Cohn E, Garabet L, Salmon JE. Predictors of Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients With Lupus: A Cohort Study. Annals of internal medicine. 2015 Aug 4:163(3):153-63. doi: 10.7326/M14-2235. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26098843]

Fakhouri F, Schwotzer N, Cabiddu G, Barratt J, Legardeur H, Garovic V, Orozco-Guillen A, Wetzels J, Daugas E, Moroni G, Noris M, Audard V, Praga M, Llurba E, Wuerzner G, Attini R, Desseauve D, Zakharova E, Luders C, Wiles K, Leone F, Jesudason S, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Kattah A, Soto-Abraham V, Karras A, Prakash J, Lightstone L, Ronco P, Ponticelli C, Appel G, Remuzzi G, Tsatsaris V, Piccoli GB. Glomerular diseases in pregnancy: pragmatic recommendations for clinical management. Kidney international. 2023 Feb:103(2):264-281. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.029. Epub 2022 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 36481180]

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Lupus Nephritis Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of LUPUS NEPHRITIS. Kidney international. 2024 Jan:105(1S):S1-S69. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.09.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38182286]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePecher AC, Henes M, Henes JC. Pregnancies in women with antineutrophil cytoplasmatic antibody associated vasculitis. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2024 Jan 1:36(1):16-20. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000977. Epub 2023 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 37682057]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSingh P, Dhooria A, Rathi M, Agarwal R, Sharma K, Dhir V, Nada R, Minz R, Suri V, Jain S, Sharma A. Successful treatment outcomes in pregnant patients with ANCA-associated vasculitides: A systematic review of literature. International journal of rheumatic diseases. 2018 Sep:21(9):1734-1740. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13342. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30345645]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFloege J, Jayne DRW, Sanders JF, Tesar V, Balk EM, Gordon CE, Adam G, Tonelli MA, Cheung M, Earley A, Rovin BH. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. Kidney international. 2024 Mar:105(3):447-449. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38388147]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWind M, Gaasbeek AGA, Oosten LEM, Rabelink TJ, van Lith JMM, Sueters M, Teng YKO. Therapeutic plasma exchange in pregnancy: A literature review. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2021 May:260():29-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.02.027. Epub 2021 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 33713886]

Kai H, Usui J, Tawara T, Takahashi-Kobayashi M, Ishii R, Tsunoda R, Fujita A, Nagai K, Kaneko S, Morito N, Saito C, Hamada H, Yamagata K. Anti-glomerular Basement Membrane Glomerulonephritis During the First Trimester of Pregnancy. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2021 Mar 1:60(5):765-770. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.5722-20. Epub 2020 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 32999239]

Kafagi AH, Li AS, Jayne D, Brix SR. Anti-GBM disease in pregnancy. BMJ case reports. 2024 Apr 30:17(4):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2023-257767. Epub 2024 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 38688578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePerrotta K, Kiernan E, Bandoli G, Manaster R, Chambers C. Pregnancy outcomes following maternal treatment with rituximab prior to or during pregnancy: a case series. Rheumatology advances in practice. 2021:5(1):rkaa074. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkaa074. Epub 2021 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 33521513]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJain AB, Reyes J, Marcos A, Mazariegos G, Eghtesad B, Fontes PA, Cacciarelli TV, Marsh JW, de Vera ME, Rafail A, Starzl TE, Fung JJ. Pregnancy after liver transplantation with tacrolimus immunosuppression: a single center's experience update at 13 years. Transplantation. 2003 Sep 15:76(5):827-32 [PubMed PMID: 14501862]

Nakai T, Honda N, Soga E, Fukui S, Kitada A, Yokogawa N, Okada M. A retrospective analysis of the safety of tacrolimus use and its optimal cut-off concentration during pregnancy in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: study from two Japanese tertiary referral centers. Arthritis research & therapy. 2024 Jan 4:26(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13075-023-03256-8. Epub 2024 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 38178242]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNevers W, Pupco A, Koren G, Bozzo P. Safety of tacrolimus in pregnancy. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2014 Oct:60(10):905-6 [PubMed PMID: 25316742]

Li R, Zhang C, Wang H, An Y. Breastfeeding by a mother taking cyclosporine for nephrotic syndrome. International breastfeeding journal. 2022 Oct 17:17(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s13006-022-00514-4. Epub 2022 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 36253832]

Kociszewska-Najman B, Mazanowska N, Borek-Dzięcioł B, Pączek L, Samborowska E, Szpotańska-Sikorska M, Pietrzak B, Dadlez M, Wielgoś M. Low Content of Cyclosporine A and Its Metabolites in the Colostrum of Post-Transplant Mothers. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 4:12(9):. doi: 10.3390/nu12092713. Epub 2020 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 32899873]