Introduction

Femoral hernias are less frequent than inguinal hernias. Recognition of a femoral hernia is an important factor in the workup and evaluation of a patient who presents with a groin bulge as the options and urgency of repair may differ from that of a more common inguinal hernia.

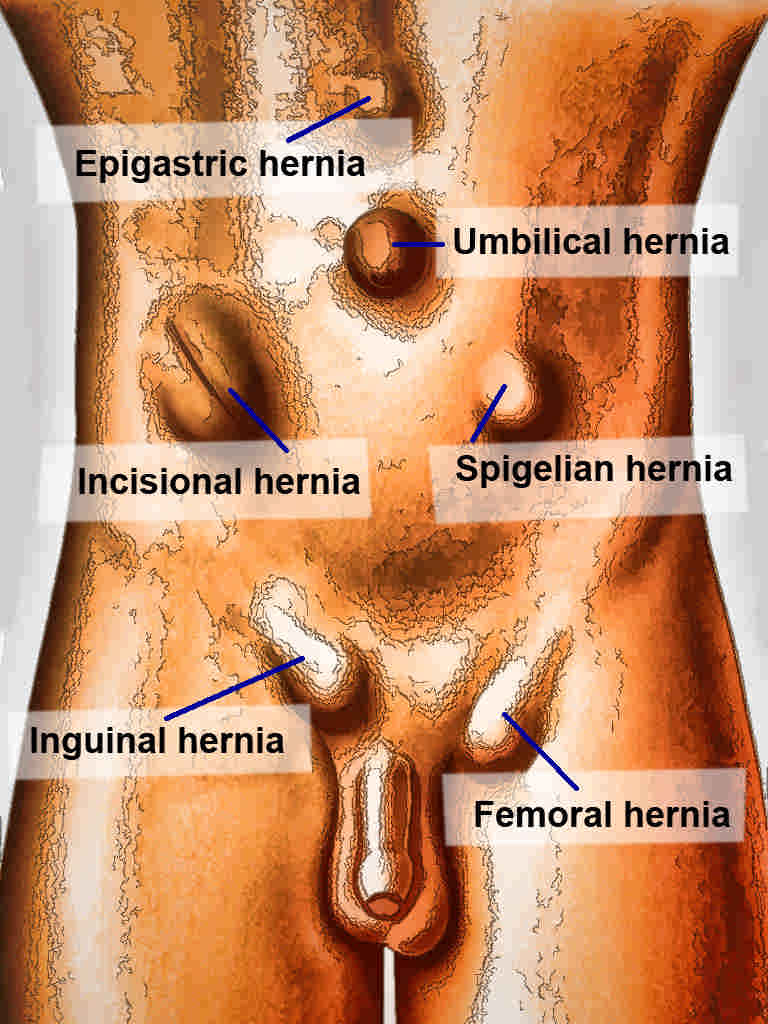

A hernia is defined as an abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue through a defect in its surrounding walls. Hernia defects may occur in various locations of the abdominal wall, but most commonly occur in the inguinal region. Hernias can occur at sites where the aponeurosis and fascia are not covered by striated muscle. As a result, the peritoneal membrane or hernia sac may protrude from the orifice or neck of a hernia.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A femoral hernia occurs in the femoral canal. It is bordered by the inguinal ligament anterosuperiorly, Cooper's ligament inferiorly, the femoral vein laterally and the junction of the iliopubic tract, and Cooper’s ligament (lacunar ligament) medially. Typically, a femoral hernia will present with a characteristic bulge below the inguinal ligament. Strangulation is the most common serious complication of a femoral hernia; these hernias have the highest rate of strangulation (15% to 20%).

Epidemiology

Lifetime occurrence of a groin hernia is 27% to 43% in men and 3% to 6% in women.[1] Femoral hernias occur less commonly than inguinal hernias and typically account for about 3% of all groin hernias. While inguinal hernias are still most common, regardless of gender, femoral hernias have a female-to-male ratio of about 10:1. Femoral hernias are rare in men. There may be other co-existing defects present at the time of diagnosis, as 10% of women and 50% of men with a femoral hernia either have or will develop an inguinal hernia. The prevalence of a femoral hernia increases with age as does the risk of complications including incarceration or strangulation.[1]

Both femoral and inguinal hernias occur more often on the right side. This is likely due to a developmental delay in closure of the processus vaginalis after the normal slower descent of the right testis during fetal development. There is agreement that the position of the sigmoid colon results in a tamponade effect on the left femoral canal, decreasing the likelihood of a left-sided defect.

History and Physical

A femoral hernia may be detected on routine physical exam, and approximately one-third of patients may be asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.[2] Typically, a small bulge is noted below the level of the inguinal ligament. On occasion, the bulge may ascend cephalad suggesting a more commonly noted inguinal hernia. Herniated preperitoneal fat is commonly noted within the hernia sac and may reduce with direct pressure or manipulation. Incarceration refers to content that cannot be reduced from within the hernia sac or defect. Strangulation occurs commonly with femoral hernias, and therefore, these patients may present urgently for evaluation. Strangulation refers to a vascular compromise to the contents of a hernia. This occurs more often in the setting of a hernia with a small neck, resulting in obstruction of arterial flow and/or venous drainage to the contents of a hernia. As a result, there may be engorgement of the hernia sac and contents with findings on exam of a painful, hard lump or mass. If small or large intestine is contained within the hernia sac, a patient may present with signs or symptoms of obstruction. Such symptoms could include nausea/vomiting, abdominal distention, abdominal pain and possibly a decrease in bowel function with an absence of flatus or bowel movements. Patients may also present with paresthesias related to compression of nearby sensory nerves by a hernia.

Evaluation

A clinician should have a high index of suspicion of a femoral hernia when evaluating a patient who presents with a bulge or painful mass in the groin region. A physical exam should be performed in both the supine and standing positions if possible. Visual inspection for asymmetry, bulges, or mass should be performed. Palpation for an inguinal defect is often done by placing a fingertip along the invaginated scrotal wall to evaluate the inguinal canal and inguinal floor. Valsalva maneuver may be helpful to assess for a bulge in identifying a hernia. Classically a bulge identified below the inguinal ligament is consistent with a femoral hernia. A careful reduction may be attempted in an otherwise asymptomatic patient, but caution should be taken to avoid manual reduction if there is pain or signs of strangulation or obstruction.

Imaging studies, including ultrasound or computed tomography (CT), can be utilized in the evaluation of a possible hernia. Both studies offer a high degree of both sensitivity and specificity in the detection of femoral and inguinal hernias. This may allow better evaluation in morbidly obese patients in whom detection may be more challenging on physical exam alone.[3] CT provides better visualization in patients who may present with incarceration or strangulation on exam. Currently, laparoscopy is not generally considered part of the diagnostic process for groin complaints and bulges.[1]

Treatment / Management

Surgical intervention remains the only cure. It is often recommended that femoral hernias be repaired at the time of diagnosis. This is mostly due to their increased incidence of complications including incarceration or strangulation, compared to the more common inguinal hernia[1]. With regards to the timing of intervention or femoral hernia repair, the finding of strangulation or obstruction presents a surgical emergency, and operative intervention should not be delayed. Femoral hernias may be repaired using a standard inguinal approach, an open pre-peritoneal approach or a minimally invasive (laparoscopic or robotic-assisted laparoscopic) approach. Regardless of technique or approach, key steps to repair of a femoral hernia include dissection and reduction of the hernia sac and closure of the defect or obliteration of the defect with the placement of a prosthetic mesh. If there is clinical concern for incarceration or strangulation, the hernia sac should be opened, and the contents examined to assess viability. The lacunar ligament may be divided, if necessary, to facilitate reduction of the hernia sac and contents. Placement of prosthetic mesh should be avoided in the setting of compromised bowel, enterotomy or gross contamination, due to concerns of infection or bacterial exposure within the operative field. Mesh infection, while uncommon, is a serious complication that may be difficult to treat and often requires an explanation of the infected prosthesis. Surgical site infection is estimated to be 2% to 4% for elective inguinal or femoral hernia repairs.[4][5](A1)

Many repairs are available, and this strongly suggests that a "best repair method" does not exist.[6] Additionally, large variations in treatments performed result from cultural differences among surgeons, different reimbursement systems, and differences in resources and logistical capabilities.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a groin mass is broad. Clinical history and physical exam findings are important factors in determining an accurate diagnosis in patients who present with a femoral hernia. Other possible diagnoses include an inguinal hernia, hydrocele/varicocele, lymphadenopathy, lipoma, cyst, abscess, hematoma, and femoral artery pseudoaneurysm/aneurysm. It is important to evaluate the contralateral groin for asymmetry to aid in determining a diagnosis. Careful examination of the external genitalia, extremity and abdomen are necessary and helpful as clinicians work through a differential diagnosis. Imaging studies (ultrasonography or CT), although costly, can also be useful in the diagnostic workup of these patients.

Prognosis

In most cases, the success of femoral hernia repair is excellent. Overall recurrence rates for groin hernias range between 5% to 10%. Tension-free techniques and mesh-based repairs, if appropriate, lead to approximately 60% reduction in ipsilateral recurrence compared to non-mesh or suture-based repairs.

Complications

Risk factors for recurrence include tobacco abuse, obesity, increased intra-abdominal pressure, coexisting infection, collagen tissue disorders, diabetes, and poor nutritional state. Most hernias recur within the first 2 years after repair. Risks and benefits discussion with patients pre-operatively should include the possibility of chronic pain following herniorrhaphy. Chronic pain may occur in up to 15% of patients following hernia repair and can affect activities of daily living in a small subset of patients.[7] In many cases, post-herniorrhaphy pain can be managed non-operatively with anti-inflammatory medications or analgesics. Other post-operative complications may include urinary retention, surgical site infection, seroma or orchitis.[8]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Most patients with a femoral hernia undergo elective repair in an outpatient setting. Surgery may be performed under general or regional anesthetic (spinal) in most situations.[9] Patients typically are asked to refrain from heavy lifting or straining and may have limitations placed upon their physical activities in the early postoperative period. The timing of return to usual activities varies depending on numerous patient factors and surgeon preference. Length of stay is longer in patients undergoing emergency repair.

Consultations

When identified on routine physical examination, patients with a femoral hernia should be referred to general surgery for consideration of elective femoral hernia repair, even if asymptomatic. As previously mentioned, this is due to the higher risk of complications including incarceration or strangulation with femoral hernias. In patients who present urgently with acute onset of pain or bulge in the femoral region or with signs or symptoms of obstruction or strangulation, an urgent evaluation must occur with timely consultation and surgical evaluation for repair.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be informed of the finding of a femoral hernia when it is detected on physical examination. It is important to educate the patient on the signs and symptoms of incarceration, strangulation, and obstruction that should prompt urgent or emergent medical/surgical evaluation. Once surgical management is deemed necessary, patients must be fully informed of the nature of the operation, together with associated operative risks and the possibility of future reoperation.

Pearls and Other Issues

Femoral hernias present typically with a mass or bulge below the level of the inguinal ligament. Femoral hernias occur most commonly in women but lower incidence overall than inguinal hernias.

Incarceration or strangulation is common with a femoral hernia due to the small size of the hernia neck or orifice.

All patients with a femoral hernia should be considered for repair due to the high risk of complications associated with femoral hernias.

Surgical techniques for repair include open (standard Cooper’s ligament repair, preperitoneal approach) and minimally invasive (standard laparoscopic or robotic-assisted laparoscopic) techniques. Patient factors and surgeon preference and technical proficiency should factor into the method of repair.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Accurate identification of a femoral hernia may pose a diagnostic dilemma. These patients may exhibit non-specific signs and symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, lower abdominal pain, and leukocytosis. The presence of a groin bulge may be due to more common etiologies such as abscess, lymphadenopathy, soft tissue mass, or other vascular pathology. The physical exam findings may reveal that the patient has a hernia; however, the exact location of the defect or type of contents within the hernia sac may not be obvious.

While the general surgeon is almost always involved in the care of patients with a femoral hernia, it is important to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include anesthesiology. The nurses are also a vital member of the interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient's vital signs. In the postoperative period for pain, wound infection and ileus; the pharmacist will ensure that the patient is on the right analgesics, antiemetics, and appropriate antibiotics if indicated. Early mobilization or ambulation is key to enhancing postoperative recovery and minimizing complications. Comprehensive care pathways have been shown to improve patient outcomes and reduce the length of stay. Prompt recognition and diagnosis with surgical consultation are recommended for all patients with a femoral hernia.

Media

References

HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2018 Feb:22(1):1-165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. Epub 2018 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 29330835]

Halgas B, Viera J, Dilday J, Bader J, Holt D. Femoral Hernias: Analysis of Preoperative Risk Factors and 30-Day Outcomes of Initial Groin Hernias Using ACS-NSQIP. The American surgeon. 2018 Sep 1:84(9):1455-1461 [PubMed PMID: 30268175]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNiebuhr H, König A, Pawlak M, Sailer M, Köckerling F, Reinpold W. Groin hernia diagnostics: dynamic inguinal ultrasound (DIUS). Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2017 Nov:402(7):1039-1045. doi: 10.1007/s00423-017-1604-7. Epub 2017 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 28812139]

Erdas E, Medas F, Pisano G, Nicolosi A, Calò PG. Antibiotic prophylaxis for open mesh repair of groin hernia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2016 Dec:20(6):765-776. doi: 10.1007/s10029-016-1536-0. Epub 2016 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 27591996]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoonchan T, Wilasrusmee C, McEvoy M, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. Network meta-analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of surgical-site infection after groin hernia surgery. The British journal of surgery. 2017 Jan:104(2):e106-e117. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10441. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28121028]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKöckerling F, Simons MP. Current Concepts of Inguinal Hernia Repair. Visceral medicine. 2018 Apr:34(2):145-150. doi: 10.1159/000487278. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29888245]

Lundström KJ, Holmberg H, Montgomery A, Nordin P. Patient-reported rates of chronic pain and recurrence after groin hernia repair. The British journal of surgery. 2018 Jan:105(1):106-112. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10652. Epub 2017 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 29139566]

Lockhart K, Dunn D, Teo S, Ng JY, Dhillon M, Teo E, van Driel ML. Mesh versus non-mesh for inguinal and femoral hernia repair. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Sep 13:9(9):CD011517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011517.pub2. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 30209805]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSunamak O, Donmez T, Yildirim D, Hut A, Erdem VM, Erdem DA, Ozata IH, Cakir M, Uzman S. Open mesh and laparoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair under spinal and general anesthesia. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2018:14():1839-1845. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S175314. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30319265]