Introduction

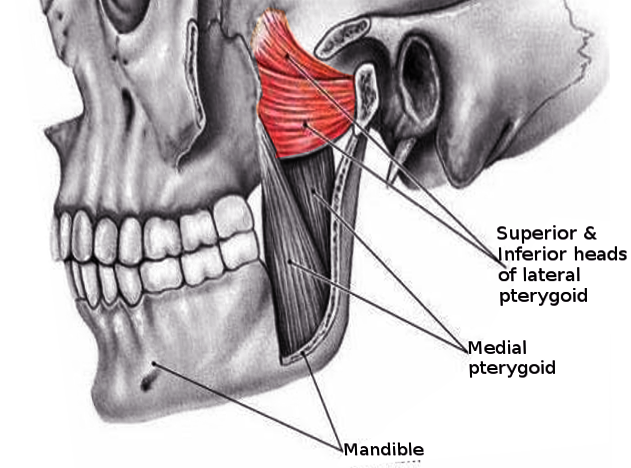

The lateral pterygoid muscle is a craniomandibular muscle that plays a crucial role in the inferior temporal region (see Image. Lateral Pterygoid Muscle). This is active during mastication and mandibular movements - including protrusion (forward movement of the mandible), abduction (depression of the mandible), and mediotrusion (mandibular condyle movement towards the midline). The muscle works particularly during speaking, singing, and clenching. The lateral pterygoid muscle has two heads or bellies. The inferior belly is three times larger than the superior belly. Among all the masticatory muscles, it is the only one with horizontally arranged fibers.[1] Functionally, the muscle is analogous to the temporalis muscle. The fan-shaped temporalis muscle exhibits a continuous range of anteroposterior movements, while the lateral pterygoid muscle exhibits a range of mediolateral and superoinferior movements.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The lateral pterygoid muscle is a single unit divided into 2 bellies with clearly identified anterior insertions and posterior attachments that remain controversial.[3] The 2 bellies of the muscle separate thanks to the different convergence of the muscle fibers.[4] The lateral pterygoid muscle is a short muscle with a triangular pyramid shape and an uppermost base.[5] The superior belly, also known as the sphenoid head, inserts anteriorly on the infratemporal surface of the sphenoid bone's greater wing and the superior quarter of the pterygoid process' lateral wing; it's posterior attachment has been widely debated, but it is believed to be inserted on the disc (anteromedial border and medial aspect) and mandibular condyle (the anterior part of the neck).[3] All authors have agreed that some fibers of the superior belly attach to the articular disc.[3] The inferior belly, also known as the pterygoid head, is three times larger than the superior belly and anteriorly attaches on: the inferior two-thirds of the lateral area of the pterygoid process' lateral wing, lateral area of the pyramidal process, and part of the maxillary bone tuberosity.[3] Its posterior attachment corresponds to the pterygoid fossa (fovea) of the neck of the mandibular condyle [3] and the temporomandibular joint capsule.

On the lateral side (superficial surface), the lateral pterygoid muscle relates to the mandibular ramus, maxillary artery, temporalis tendon, and the masseter muscle. On the medial side (deep surface), the muscle is related to the mandibular nerve, the middle meningeal artery, the sphenomandibular ligament, and the upper part of the medial pterygoid muscle. Deep temporal and masseteric nerves and vessels emerge from the upper border of the superior belly. The lingual and inferior alveolar nerve and vessels pass beneath the lower edge of the inferior belly, and the second part of the maxillary artery runs between the two bellies to enter the pterygomaxillary fissure. The buccal nerve and respective blood vessels traverse the two bellies of the lateral pterygoid muscle mediolaterally. The two bellies of the lateral pterygoid muscle were always believed to have an antagonist action due to their different anterior insertions. However, results from recent studies suggest that they may function similarly. This is due to errors when interpreting electromyography (EMG) studies, where the sensors' position couldn't be precisely determined.

The inferior belly was classically described to function in depressing, protruding, and deviating the mandible to the contralateral side. The superior belly was mostly believed to become active during the elevation of the mandible to close the mouth. However, the superior belly may have little role in closing the mouth and may become active during mouth opening, protrusion, and contralateral deviation, just like the inferior belly. The lateral pterygoid muscle depresses the mandible and opens the mouth when assisted by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and the mylohyoid muscle. Among all the four muscles of mastication (medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid, masseter, and temporalis), the lateral pterygoid is the only muscle that participates in depressing the mandible. The unilateral contraction of the lateral pterygoid muscle with the ipsilateral medial pterygoid muscle results in lateral mandibular movement to the contralateral side. This movement is observable during functional and parafunctional lateral excursive movements, i.e., during chewing stroke, masticating, and clenching. When both bellies of the lateral pterygoid muscle contract bilaterally, the mandible travels anteriorly (protrusion).

Unlike the jaw-closing muscles, this jaw depressor does not contain muscle spindles. Due to the absence of muscle spindles, the lateral pterygoid muscle plays a secondary role during the mandibular depression. Muscle spindles (stretch receptors) are required to detect any change in the working length and velocity of the muscle. During functional movements, this prevents excessive muscle stretching. The lateral pterygoid muscle plays a crucial role in controlling the function of the jaw and temporomandibular joint; this also appears to function during the generation of horizontal forces required during mastication and parafunctional activities.[6][7] There have been suggestions that some fibers of the superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle become active during clenching; this prevents the mandibular condyle from being displaced posteriorly, thus, avoiding the exertion of pressure on the sensitive postcondylar structures.[8]

Embryology

The entire masticatory musculature originates from the mesoderm of the first branchial arch. During the third month of intrauterine life, the muscle inserts into the mesenchyme, condensing around the mandible's developing condyle. A part of the muscle's tendon sweeps above the condyle and inserts into the portion of the Meckel's cartilage (cartilaginous bar of the mandibular arch) that forms the head of the malleus. A part of the tendon also gets inserted into the articular disc of the temporomandibular joint. The lateral pterygoid muscle reaches its mature shape by week 14 of intrauterine life. At this stage, the muscle is divided by aponeurosis forming three defined regions: superior, inferomedial, and inferoanterior.[9] The inferomedial part attaches to the anteromedial area of the mandibular condyle and disc, whereas the inferoanterior part inserts in the anterior region of the condyle.[9] The superior muscular band inserts in the disc superiorly and medially.[9]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The lateral pterygoid muscles receive their blood supply from the pterygoid branch of the maxillary artery.

Nerves

The lateral pterygoid muscle receives innervation from the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve. The main trunk of the mandibular nerve divides into the anterior and the posterior division. The anterior division gives off three motor branches. One of the motor branches is the nerve to the lateral pterygoid, a paired nerve (one for each belly) innervating the lateral pterygoid muscle. According to some authors, this muscle may also receive innervation from the anterior, middle, and posterior deep temporal nerves, the masseteric nerve, and sometimes from the buccal nerve. They innervate different muscle parts, resulting in selective activation, which ensures coordination of movements and reduces stress on the temporomandibular joint. There is a general acceptance that the lateral pterygoid muscle is innervated by the lateral pterygoid nerve, which arises from the mandibular nerve.[3] Although both bellies receive their innervation from the mandibular nerve, different nerves may innervate each of them.[4][10] Kim et al described a typical nerve distribution pattern where the superior belly is innervated by the buccal nerve and the inferior belly by the mandibular nerve trunk.[10]

Physiologic Variants

The lateral pterygoid muscle is generally two-headed (95.5%). Some study results show a lateral pterygoid muscle with a single head;[11][5] others found very rare cases of 3 heads. The 3-headed variant of the muscle consists of the superior, medial, and inferior head.[5]

Surgical Considerations

The lateral pterygoid muscle is located deeply in the inferior temporal fossa. The inaccessibility of this region and its surrounding tissue makes the anatomical dissection of the muscle a challenging task.[1]

Clinical Significance

The spasm of the lateral pterygoid muscle can be painful and result in trismus (locked jaw), and the patient may require analgesics or muscle relaxants. Some authors believe that during temporomandibular disorders, this muscle plays an important role. This involvement may be due to the absence of coordination between the muscle's superior and inferior bellies. This lack of coordination leads to disturbance in the horizontal positioning of the intra-articular disc relative to the condyle.[12] Clinical examination of patients with such disorders reveals pain in this muscle region during jaw movements and with palpation behind the tuberosity region.[2] In the internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint, there are implications that the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle plays a role in causing anterior dislocation of the disk.[13] The prolonged contraction of the muscle places forward traction on the disk, resulting in anterior displacement of the disk.[14]

Clinical Significance in Prosthodontics

Long-term completely edentulous patients wearing dentures with worn-out occlusal surfaces of the artificial teeth tend to position their mandible in the forward and lateral position. The dentist may notice different anteroposterior/lateral teeth contact positions during subsequent appointments, which poses difficulty in fabricating a new complete denture, particularly during the recording of the maxillomandibular relations. There have been suggestions that this variation in the position of the mandible during resting jaw posture is a result of an attempt to attain a reasonable bite with worn-out dentures. Some authors believe that the lateral pterygoid muscle's lower and upper belly plays a significant role in maintaining the mandible at this new anterior position. The variations in the activity levels between the two bellies on each side determine the lateral and anteroposterior positioning of the jaw.[2] The origin of both the bellies of the lateral pterygoid muscle is medial to their insertions. Thus, the wide opening of the mandible may temporarily result in the mandible undergoing distortion in the transverse plane. Therefore, during impression making of the lower arch, if the mouth is widely open, it may result in an impression that is not accurate in the transverse dimension due to mandibular flexion.

Other Issues

Some parafunctional movements of the jaw are characterized by protrusion and side-to-side movements of the mandible. Such actions are associated with large jaw-closing muscle activity, necessitating sizeable horizontal force vectors to overcome the frictional resistance between the teeth. The inferior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle and the superior belly play a vital role in generating these horizontal forces.[2]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Stöckle M, Fanghänel J, Knüttel H, Alamanos C, Behr M. The morphological variations of the lateral pterygoid muscle: A systematic review. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2019 Mar:222():79-87. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2018.10.006. Epub 2018 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 30394300]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMurray GM, Phanachet I, Uchida S, Whittle T. The human lateral pterygoid muscle: a review of some experimental aspects and possible clinical relevance. Australian dental journal. 2004 Mar:49(1):2-8 [PubMed PMID: 15104127]

Desmons S, Graux F, Atassi M, Libersa P, Dupas PH. The lateral pterygoid muscle, a heterogeneous unit implicated in temporomandibular disorder: a literature review. Cranio : the journal of craniomandibular practice. 2007 Oct:25(4):283-91 [PubMed PMID: 17983128]

Usui A, Akita K, Yamaguchi K. An anatomic study of the divisions of the lateral pterygoid muscle based on the findings of the origins and insertions. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2008 Jun:30(4):327-33. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0329-2. Epub 2008 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 18317664]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEl Haddioui A, Laison F, Zouaoui A, Bravetti P, Gaudy JF. Functional anatomy of the human lateral pterygoid muscle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2005 Nov:27(4):271-86 [PubMed PMID: 16200387]

Wood WW, Takada K, Hannam AG. The electromyographic activity of the inferior part of the human lateral pterygoid muscle during clenching and chewing. Archives of oral biology. 1986:31(4):245-53 [PubMed PMID: 3459415]

Widmalm SE, Lillie JH, Ash MM Jr. Anatomical and electromyographic studies of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 1987 Sep:14(5):429-46 [PubMed PMID: 3478452]

Phanachet I, Whittle T, Wanigaratne K, Klineberg IJ, Sessle BJ, Murray GM. Functional heterogeneity in the superior head of the human lateral pterygoid. Journal of dental research. 2003 Feb:82(2):106-11 [PubMed PMID: 12562882]

Ogütcen-Toller M, Juniper RP. The embryologic development of the human lateral pterygoid muscle and its relationships with the temporomandibular joint disc and Meckel's cartilage. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 1993 Jul:51(7):772-8; discussion 778-9 [PubMed PMID: 8509918]

Kim HJ, Kwak HH, Hu KS, Park HD, Kang HC, Jung HS, Koh KS. Topographic anatomy of the mandibular nerve branches distributed on the two heads of the lateral pterygoid. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2003 Aug:32(4):408-13 [PubMed PMID: 14505626]

Abe S, Takasaki I, Ichikawa K, Ide Y. Investigations of the run and the attachment of the lateral pterygoid muscle in Japanese. The Bulletin of Tokyo Dental College. 1993 Aug:34(3):135-9 [PubMed PMID: 8181110]

Juniper RP. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction: a theory based upon electromyographic studies of the lateral pterygoid muscle. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 1984 Feb:22(1):1-8 [PubMed PMID: 6582927]

Taskaya-Yilmaz N, Ceylan G, Incesu L, Muglali M. A possible etiology of the internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint based on the MRI observations of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2005 Mar:27(1):19-24 [PubMed PMID: 15750717]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWongwatana S, Kronman JH, Clark RE, Kabani S, Mehta N. Anatomic basis for disk displacement in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 1994 Mar:105(3):257-64 [PubMed PMID: 8135209]