Introduction

ARDS is an acute, diffuse, inflammatory form of lung injury and life-threatening condition in seriously ill patients, characterized by poor oxygenation, pulmonary infiltrates, and acute onset. On a microscopic level, the disorder is associated with capillary endothelial injury and diffuse alveolar damage.

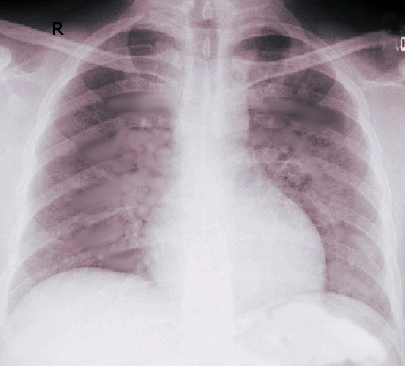

ARDS is an acute disorder that starts within seven days of the inciting event and is characterized by bilateral lung infiltrates and severe progressive hypoxemia in the absence of any evidence of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. According to the Berlin definition, ARDS is defined by acute onset, bilateral lung infiltrates on chest radiography or CT scan of a non-cardiac origin, and a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of less than 300 mm Hg. The Berlin definition differs from the previous American-European Consensus definition by excluding the term acute lung injury; it also removed the requirement for wedge pressure <18 mm Hg and included the requirement of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) of greater than or equal to 5 cm H20.

Once ARDS develops, patients usually have varying degrees of pulmonary artery vasoconstriction and may subsequently develop pulmonary hypertension. ARDS carries a high mortality, and few effective therapeutic modalities exist to combat this condition.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

ARDS has many risk factors. Besides pulmonary infection or aspiration, extra-pulmonary sources include sepsis, trauma, massive transfusion, drowning, drug overdose, fat embolism, inhalation of toxic fumes, and pancreatitis. These extra-thoracic illnesses and injuries trigger an inflammatory cascade, culminating in pulmonary injury.[3]

A lung injury prevention score helps identify low-risk patients, but a high score is less helpful.[1]

Some risk factors for ARDS include:

- Advanced age

- Female gender

- Smoking

- Alcohol use

- Aortic vascular surgery

- Cardiovascular surgery

- Traumatic brain injury [2]

- Pancreatitis

- Pulmonary contusion

- Infectious pneumonia

- Drugs (radiation, chemotherapeutic agents, amiodarone)

Epidemiology

Estimates of the incidence of ARDS in the United States range from 64.2 to 78.9 cases/100,000 person-years. Twenty-five percent of ARDS cases are initially classified as mild, and 75% as moderate or severe. However, a third of the mild cases progress to moderate or severe disease.[3][4] Approximately 10 to 15% of patients admitted to the intensive care units and up to 23% of mechanically ventilated patients meet the criteria for ARDS.[5] A literature review revealed a mortality decrease of 1.1% per year from 1994 through 2006. However, the overall pooled mortality rate for all the studies evaluated was 43%.[6][7] The mortality of ARDS is commensurate with the severity of the disease: 27%, 32%, and 45% for mild, moderate, and severe disease, respectively.

Pathophysiology

ARDS represents a stereotypic response to various etiologies. ARDS progresses through different phases, starting with alveolar-capillary damage, a proliferative phase characterized by improved lung function and healing, and a final fibrotic phase signaling the end of the acute disease process. The pulmonary epithelial and endothelial cellular damage is characterized by inflammation, apoptosis, necrosis, and increased alveolar-capillary permeability, leading to alveolar edema and proteinosis. Alveolar edema, in turn, reduces gas exchange, leading to hypoxemia. A hallmark of the pattern of injury seen in ARDS is that it is not uniform. Segments of the lung may be more severely affected, resulting in decreased regional lung compliance, which classically involves the bases more than the apices. Intrapulmonary differential in pathology results in a variant response to oxygenation strategies, such as increased positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), which may improve oxygen diffusion in affected alveoli but may cause volutrauma and atelectrauma of adjacent unaffected alveoli.[8] Ultimately, this injury manifests as impaired gas exchange, decreased lung compliance, and pulmonary hypertension.[9]

Histopathology

The key histologic changes in ARDS reveal the presence of alveolar edema in diseased lung areas. The type I pneumocytes and vascular endothelium are injured, which results in the leaking of proteinaceous fluid and blood into the alveolar airspace. Other findings may include alveolar hemorrhage, pulmonary capillary congestion, interstitial edema, and hyaline membrane formation. None of these changes are specific to the disease.[8]

History and Physical

The syndrome is characterized by dyspnea and hypoxemia, progressively worsening within 6 to 72 hours of the inciting event, frequently requiring mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit-level care. The history is directed at identifying the underlying cause that precipitated the disease. When interviewing patients who can communicate, they often start to complain of mild dyspnea initially. Within 12 to 24 hours, the respiratory distress escalates, becoming severe and requiring mechanical ventilation to prevent hypoxia. The etiology may be obvious in the case of pneumonia or sepsis. However, in other cases, questioning the patient or relatives on recent exposures may also be paramount in identifying the causative agent.

The physical examination will include findings associated with the respiratory system, such as tachypnea and increased breathing effort. Systemic signs may also be evident depending on the severity of the illness, such as central or peripheral cyanosis resulting from hypoxemia, tachycardia, and altered mental status. Despite 100% oxygen, patients have low oxygen saturation. Chest auscultation usually reveals rales, especially bibasilar, but can often be auscultated throughout the chest.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of ARDS is based on the following criteria: acute onset, bilateral lung infiltrates on chest radiography or CT scan (who are of non-cardiac origin), and a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of less than 300 mm Hg. It is further sub-classified into mild (PaO2/FiO2 >200 mm Hg, but ≤300 mm Hg), moderate (PaO2/FiO2 >100 mm Hg, but ≤ 200 mm Hg), and severe (PaO2/FiO2 ≤100 mm Hg) subtypes. Mortality and ventilator-free days increase with severity. A CT scan of the chest may be helpful in cases of pneumothorax, pleural effusion, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, or barotrauma to correctly identify infiltrates as pulmonic in origin.

Assessing left ventricular function is crucial to differentiate ARDS from congestive heart failure or to understand heart failure's contribution to the patient's condition. This assessment can be done through invasive methods like pulmonary artery catheter measurements or noninvasive techniques such as cardiac echocardiography, thoracic bioimpedance, or pulse contour analysis. However, using pulmonary artery catheters is controversial and generally discouraged, with a preference for noninvasive methods. Bronchoscopy may be required to assess pulmonary infections and obtain material for culture.[2]

Further laboratory and radiographic tests are guided by the underlying cause of the inflammatory process leading to ARDS. Patients with ARDS often develop or have concurrent multi-organ failure, affecting renal, hepatic, and hematopoietic systems. Regular testing, including complete blood count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum magnesium, serum ionized calcium, phosphorus levels, blood lactate level, coagulation panel, troponin, cardiac enzymes, and CKMB, is recommended as clinically indicated.[10][11][12]

Treatment / Management

The chief treatment strategy is supportive care, focusing on 1) reducing shunt fraction, 2) increasing oxygen delivery, 3) decreasing oxygen consumption, and 4) avoiding further injury. Patients are mechanically ventilated, guarded against fluid overload with diuretics, and given nutritional support until improvement is observed. Interestingly, the mode in which a patient is ventilated affects lung recovery. Evidence suggests that some ventilatory strategies can exacerbate alveolar damage and perpetuate lung injury in the context of ARDS. Care is placed on preventing volutrauma (exposure to large tidal volumes), barotrauma (exposure to high plateau pressures), and atelectrauma (exposure to atelectasis).[1][13](A1)

A lung-protective ventilatory strategy is advocated to reduce lung injury. The NIH-NHLBI ARDS Clinical Network Mechanical Ventilation Protocol (ARDSnet) sets the following goals: tidal volume (TV) from 4 to 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW), respiratory rate (RR) up to 35 bpm, SpO2 88% to 95%, plateau pressure (Pp) less than 30 cm H2O, pH goal 7.30 to 7.45, and inspiratory-to-expiratory time ratio less than 1. To maintain oxygenation, ARDSnet recognizes the benefit of PEEP. The protocol allows for a low or a high PEEP strategy relative to FiO2. Either strategy tolerates a PEEP of up to 24 cm H2O in patients requiring 100% FiO2. The inspiratory-to-expiratory time ratio goal may need to be sacrificed, and an inverse inspiratory-to-expiratory time ratio strategy may need to be instituted to improve oxygenation in particular clinical situations.

Novel invasive ventilation strategies have been developed to improve oxygenation. These include airway pressure release ventilation (APRV) and high-frequency oscillation ventilation (children). Recruitment maneuvers and APRV have not been shown to improve mortality but may improve oxygenation. Patients with mild and some with moderate ARDS may benefit from non-invasive ventilation to avoid endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation. These modalities include continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bi-level airway pressure (BiPAP), proportional-assist ventilation, and a high-flow nasal cannula. Adequate care should be taken to intubate and mechanically ventilate these patients if they get worse on the above non-invasive ventilation.

Several strategies can be employed to reduce the risk of barotrauma in ARDS management to achieve Pp less than 30 cm H2O. One effective approach involves maintaining TV and minimizing PEEP as much as possible. Additionally, increasing the rise or inspiration time can aid in meeting the Pp target. Decreasing the flow rate can also serve as a supplementary method to lower Pp.

Improving lung compliance will improve Pp and oxygenation goal attainment. Neuromuscular blockade has been used as an aid to improving compliance. Neuromuscular blockers instituted during the first 48 hours of ARDS improved 90-day survival and increased time off the ventilator.[13] However, the most recent trial published in 2019 showed no significant difference in mortality with continuous infusion of people with paralysis compared to lighter sedation goals.[14] (A1)

Other causes of decreased lung compliance should be sought and addressed. These include but are not limited to pneumothorax, hemothorax, thoracic compartment syndrome, and intraabdominal hypertension. Prone position has shown benefits in about 50% to 70% of patients. The improvement in oxygenation is rapid and allows a reduction in FiO2 and PEEP. The prone position is safe, but there is a risk of dislodgement of lines and tubes. The prone position is believed to facilitate the recruitment of dependent lung zones, improve diaphragmatic excursion, and increase functional residual capacity. The patient must be prone for at least 8 hours a day to derive the benefits.

Nonventilatory strategies have included prone positioning and conservative fluid management once resuscitation has been achieved.[15][16] Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has recently been advocated as salvage therapy in refractory hypoxemic ARDS.[17] However, two major trials that compared venovenous ECMO to standard care showed no difference in mortality between the two groups.[18] Nutritional support via enteral feeding is recommended. A high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet containing gamma-linolenic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid has been shown in some studies to improve oxygenation. A moderately permissive hyperglycemic strategy, blood glucose 140 to 180 mg/dL, is recommended for most hyperglycemic critically ill patients, rather than intensive insulin therapy targeting blood glucose 80 to 110 mg/dL. Critically ill patients are more prone to deep venous thrombosis, so some form of prophylaxis is recommended. Likewise, prophylaxis against stress ulcers is advised for increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.(A1)

Glucocorticoids can be administered in patients in whom ARDS has been precipitated by a steroid-responsive process (eg, acute eosinophilic pneumonia) and to those with refractory sepsis or community-acquired pneumonia. Most patients who have persistent or refractory moderate to severe ARDS are relatively early in the disease course (within 14 days of onset with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio <200 mm Hg) despite initial management with standard therapies, including low tidal volume ventilation, can also be managed with glucocorticoids.[19] However, glucocorticoids are generally avoided in patients with less severe ARDS or those with persistent ARDS beyond 14 days. Moreover, their use is associated with worse outcomes in patients with certain viral infections, including influenza.[20](A1)

Central venous catheters may be helpful for frequent blood draws, administration of vasopressors, and measurement of central venous pressure.

Care must also be taken to prevent pressure sores. Frequent patient repositioning or turning is recommended when feasible. Skin checks per nursing routine are also advised. Physical therapy should involve exercising the patient when they are weaned from mechanical ventilation and stable to participate in treatment. No role for the routine administration of mucolytics is proven in these patients.[21](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for ARDS include the following:

- Cardiogenic edema

- Exacerbation of interstitial lung disease

- Acute interstitial pneumonia

- Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage

- Acute eosinophilic lung disease

- Organizing pneumonia

- Bilateral pneumonia

- Pulmonary vasculitis

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

- Disseminated malignancy

Prognosis

The prognosis for ARDS was abysmal until very recently. There are reports of 30% to 40% mortality up until the 1990s, but over the past 20 years, there has been a significant decrease in the mortality rate, even for severe ARDS. These accomplishments are secondary to a better understanding of and advancements in mechanical ventilation and earlier antibiotic administration and selection. The primary cause of death in patients with ARDS was sepsis or multiorgan failure. While mortality rates are now around 9% to 20%, it is much higher in older patients. ARDS has significant morbidity as these patients remain in the hospital for extended periods and have significant weight loss, poor muscle function, and functional impairment. Hypoxia from the inciting illness also leads to various cognitive changes that may persist for months after discharge. As measured by functional testing, there is an almost near-complete return of pulmonary capacity for many survivors. Nonetheless, many patients report feelings of dyspnea on exertion and decreased exercise tolerance. This ARDS sequela makes returning to a normal life challenging for these patients as they adjust to a new baseline.[22][23]

Complications

Complications of ARDS include the following:

- Barotrauma from high PEEP

- Prolonged mechanical ventilation (necessitating tracheostomy)

- Post-extubation laryngeal edema and subglottic stenosis

- Nosocomial infections

- Pneumonia

- Line sepsis

- Urinary tract infection

- Deep venous thrombosis

- Antibiotic resistance

- Muscle weakness

- Renal failure

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Tracheostomy and Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy

Many patients with ARDS require a tracheostomy and a percutaneous feeding tube (PEG) in the recovery phase. The tracheostomy facilitates weaning from the ventilator, making it easy to clear the secretions and more comfortable. The tracheostomy is usually performed at 2 to 3 weeks, followed by a PEG.

Nutritional Support

Most patients with ARDS have difficulty eating, and muscle wasting is very common. These patients are either given enteral or parenteral feeding, depending on the condition of the gastrointestinal tract. Some experts recommend a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet as it has anti-inflammatory and vasodilating effects. Almost every type of nutritional supplement has been studied in patients with ARDS, but none has proven to be the magic bullet.

Activity

Since patients with ARDS are bed-bound, frequent position changes are highly recommended to prevent bedsores and deep venous thrombosis. One can minimize the sedation in alert patients and sit them in a chair.

Consultations

Care of patients with ARDS requires an interprofessional team of healthcare workers that includes the following:

- Pulmonologist

- Respiratory therapist

- Intensivist

- Infectious disease specialist

- Dietitian

Deterrence and Patient Education

Even though many risk factors for ARDS are known, there is no way to prevent ARDS proactively. However, careful management of fluids in high-risk patients can be helpful. Steps should be taken to avoid aspiration by keeping the head of the bed elevated before feeding. Employing a lung-protective mechanical ventilation strategy in patients at high risk for ARDS could aid in preventing the onset of this condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

ARDS is a severe disorder of the lungs with the potential to cause death. Patients with ARDS may require mechanical ventilation because of hypoxia.[24] The management is usually in the ICU with an interprofessional healthcare team. ARDS has effects beyond the lung. Prolonged mechanical ventilation often leads to bedsores, deep venous thrombosis, multisystem organ failure, weight loss, and poor overall functioning. It is essential to have an integrated approach to ARDS management because it usually affects many organs in the body. These patients need nutritional support, chest physiotherapy, treatment for sepsis if present, and potentially hemodialysis. Many of these patients remain in the hospital for months, and even those who survive face severe challenges due to a loss of muscle mass and cognitive changes (due to hypoxia). Evidence shows that an interprofessional team approach improves outcomes by facilitating communication and ensuring timely intervention.[25] The team and responsibilities should consist of the following:

- Intensivist: Manages ventilator use and ICU issues like pneumonia prevention and DVT prophylaxis.

- Dietitian and Nutritionist: Provide nutritional support.

- Respiratory Therapist: Oversees ventilator settings.

- Pharmacist: Manages medications, including antibiotics, anticoagulants, and diuretics.

- Pulmonologist: Addresses lung diseases.

- Nephrologist: Manages kidney health and renal replacement therapy.

- Nurses: Monitor patient health, assist with movement, and educate families.

- Physical Therapist: Aids in regaining muscle function.

- Tracheostomy Nurse: Helps with tracheostomy maintenance and weaning.

- Mental Health Nurse: Assesses psychological well-being.

- Social Worker: Manages rehabilitation transfers, follow-up care, and any financial issues the patient may have.

- Chaplain: Provides spiritual support.

Outcomes

Despite advances in critical care, ARDS still has high morbidity and mortality. Even those who survive can have a poorer quality of life. While many risk factors are known for ARDS, there is no way to prevent the condition. Besides restricting fluids in high-risk patients, close monitoring for hypoxia by the team is vital. The earlier the hypoxia is identified, the better the outcome. Those who survive have a lengthy recovery period to regain functional status. Many continue to have dyspnea even with mild exertion and thus depend on care from others.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, Adesanya A, Chang SY, Hou P, Anderson H 3rd, Hoth JJ, Mikkelsen ME, Gentile NT, Gong MN, Talmor D, Bajwa E, Watkins TR, Festic E, Yilmaz M, Iscimen R, Kaufman DA, Esper AM, Sadikot R, Douglas I, Sevransky J, Malinchoc M, U.S. Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group: Lung Injury Prevention Study Investigators (USCIITG-LIPS). Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011 Feb 15:183(4):462-70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC. Epub 2010 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 20802164]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang Y, Zhang L, Xi X, Zhou JX, China Critical Care Sepsis Trial (CCCST) Workgroup. The Association Between Etiologies and Mortality in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Multicenter Observational Cohort Study. Frontiers in medicine. 2021:8():739596. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.739596. Epub 2021 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 34733862]

Zambon M, Vincent JL. Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest. 2008 May:133(5):1120-7. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2134. Epub 2008 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 18263687]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShrestha GS, Khanal S, Sharma S, Nepal G. COVID-19: Current Understanding of Pathophysiology. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2020 Nov 13:18(3):351-359. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i3.3028. Epub 2020 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 33210623]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A, LUNG SAFE Investigators, ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016 Feb 23:315(8):788-800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26903337]

Sedhai YR, Yuan M, Ketcham SW, Co I, Claar DD, McSparron JI, Prescott HC, Sjoding MW. Validating Measures of Disease Severity in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2021 Jul:18(7):1211-1218. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-772OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33347379]

Sharma NS, Lal CV, Li JD, Lou XY, Viera L, Abdallah T, King RW, Sethi J, Kanagarajah P, Restrepo-Jaramillo R, Sales-Conniff A, Wei S, Jackson PL, Blalock JE, Gaggar A, Xu X. The neutrophil chemoattractant peptide proline-glycine-proline is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2018 Nov 1:315(5):L653-L661. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00308.2017. Epub 2018 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 30091378]

Huang D, Ma H, Xiao Z, Blaivas M, Chen Y, Wen J, Guo W, Liang J, Liao X, Wang Z, Li H, Li J, Chao Y, Wang XT, Wu Y, Qin T, Su K, Wang S, Tan N. Diagnostic value of cardiopulmonary ultrasound in elderly patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2018 Aug 13:18(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0666-9. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30103730]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVieillard-Baron A, Schmitt JM, Augarde R, Fellahi JL, Prin S, Page B, Beauchet A, Jardin F. Acute cor pulmonale in acute respiratory distress syndrome submitted to protective ventilation: incidence, clinical implications, and prognosis. Critical care medicine. 2001 Aug:29(8):1551-5 [PubMed PMID: 11505125]

Chen WL, Lin WT, Kung SC, Lai CC, Chao CM. The Value of Oxygenation Saturation Index in Predicting the Outcomes of Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Aug 8:7(8):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7080205. Epub 2018 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 30096809]

Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: An Update and Review. Journal of translational internal medicine. 2018 Jun:6(2):74-77. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0012. Epub 2018 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 29984201]

Cherian SV, Kumar A, Akasapu K, Ashton RW, Aparnath M, Malhotra A. Salvage therapies for refractory hypoxemia in ARDS. Respiratory medicine. 2018 Aug:141():150-158. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.030. Epub 2018 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 30053961]

Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T, Mercier E, Badet M, Mercat A, Baudin O, Clavel M, Chatellier D, Jaber S, Rosselli S, Mancebo J, Sirodot M, Hilbert G, Bengler C, Richecoeur J, Gainnier M, Bayle F, Bourdin G, Leray V, Girard R, Baboi L, Ayzac L, PROSEVA Study Group. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Jun 6:368(23):2159-68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. Epub 2013 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 23688302]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network, Moss M, Huang DT, Brower RG, Ferguson ND, Ginde AA, Gong MN, Grissom CK, Gundel S, Hayden D, Hite RD, Hou PC, Hough CL, Iwashyna TJ, Khan A, Liu KD, Talmor D, Thompson BT, Ulysse CA, Yealy DM, Angus DC. Early Neuromuscular Blockade in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2019 May 23:380(21):1997-2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901686. Epub 2019 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 31112383]

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF Jr, Hite RD, Harabin AL. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Jun 15:354(24):2564-75 [PubMed PMID: 16714767]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrodie D, Bacchetta M. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for ARDS in adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Nov 17:365(20):1905-14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1103720. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22087681]

Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, Demoule A, Lavoué S, Guervilly C, Da Silva D, Zafrani L, Tirot P, Veber B, Maury E, Levy B, Cohen Y, Richard C, Kalfon P, Bouadma L, Mehdaoui H, Beduneau G, Lebreton G, Brochard L, Ferguson ND, Fan E, Slutsky AS, Brodie D, Mercat A, EOLIA Trial Group, REVA, and ECMONet. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 May 24:378(21):1965-1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29791822]

Yang P, Formanek P, Scaglione S, Afshar M. Risk factors and outcomes of acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology research : the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 2019 Mar:49(3):335-343. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13240. Epub 2018 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 30084205]

Annane D, Pastores SM, Rochwerg B, Arlt W, Balk RA, Beishuizen A, Briegel J, Carcillo J, Christ-Crain M, Cooper MS, Marik PE, Umberto Meduri G, Olsen KM, Rodgers S, Russell JA, Van den Berghe G. Correction to: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) in critically ill patients (Part I): Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) 2017. Intensive care medicine. 2018 Mar:44(3):401-402. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5071-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29476199]

Rodrigo C, Leonardi-Bee J, Nguyen-Van-Tam J, Lim WS. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of influenza. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Mar 7:3():CD010406. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010406.pub2. Epub 2016 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 26950335]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAnand R, McAuley DF, Blackwood B, Yap C, ONeill B, Connolly B, Borthwick M, Shyamsundar M, Warburton J, Meenen DV, Paulus F, Schultz MJ, Dark P, Bradley JM. Mucoactive agents for acute respiratory failure in the critically ill: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2020 Aug:75(8):623-631. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-214355. Epub 2020 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 32513777]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGadre SK, Duggal A, Mireles-Cabodevila E, Krishnan S, Wang XF, Zell K, Guzman J. Acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Medicine. 2018 Apr:97(17):e0487. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010487. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29703009]

Chiumello D, Coppola S, Froio S, Gotti M. What's Next After ARDS: Long-Term Outcomes. Respiratory care. 2016 May:61(5):689-99. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04644. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27121623]

Villar J, Schultz MJ, Kacmarek RM. The LUNG SAFE: a biased presentation of the prevalence of ARDS! Critical care (London, England). 2016 Apr 25:20(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1273-x. Epub 2016 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 27109238]

Bos LD, Cremer OL, Ong DS, Caser EB, Barbas CS, Villar J, Kacmarek RM, Schultz MJ, MARS consortium. External validation confirms the legitimacy of a new clinical classification of ARDS for predicting outcome. Intensive care medicine. 2015 Nov:41(11):2004-5. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3992-x. Epub 2015 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 26202043]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence