Introduction

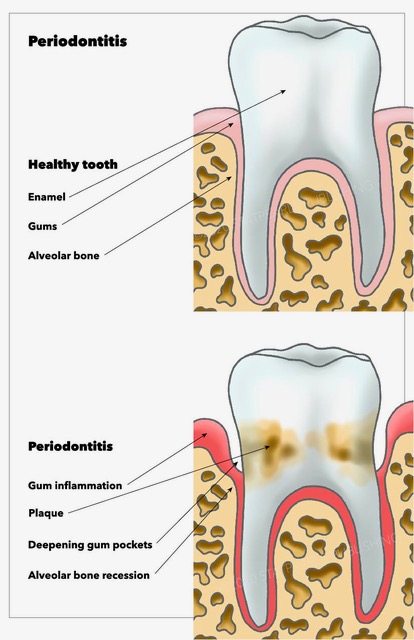

Approximately 700 species of microorganisms colonize the human oral cavity.[1] These bacteria inhabiting the human oral cavity are mainly commensals along with a sparse population of pathogenic bacteria.[2] Periodontitis is one of the most common ailments affecting the teeth, leading to the destruction of the supporting and surrounding tooth structure. [3] The term "periodontitis" is build up of two words, i.e., "periodont-" meaning "structure surrounding the teeth" and "itis" means "inflammation." Periodontitis is originally a disease originating from the gingival tissue which if left untreated results in penetration of inflammation to the deeper tissues, altering the bone homeostasis causing tooth loss.[3] Periodontal disease has a multifactorial origin.[4] The main culprit identified in periodontitis is the bacterial biofilm growing on the tooth surfaces.[5][6] While the host response determines the progression of the disease along with factors like local factors like plaque and calculus, genetics, environmental factors, systemic health of the patient, lifestyle habits and various social determinants also play a role.[4] The deleterious effects of periodontopathogens are not limited to the periodontium, but they also exude their ill effects on the systemic health of the patients.[7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The primary causative agent resulting in periodontal disease is the mixed bacterial colonization in the oral tissue.[2][8] While there are other factors which act as secondary etiologic factors accelerating the propagation and development of periodontal diseases like developmental grooves, calculus, dental plaque, overhanging restorations, anatomical features like the short trunk, cervical enamel projections, systemic factors, genetic factors, smoking, and stress.[9][10]

Loe et al. 1965, by their pioneering study of "Experimental Gingivitis in Man" confirmed the role of dental plaque in the genesis of gingival and periodontal disease.[11] Within a span of 7 to 21 days following discontinuation of oral hygiene measures results in the development of gingivitis. This development of gingivitis is a reversible process within 7 to 10 days after the reestablishment of the oral hygiene measures.[11] Further studies by Theilade et al. 1966 demonstrated the bacteriological backing behind the shift of gram-positive bacterial population associated with periodontal health to a predominant gram-negative bacterial population associated with periodontal disease.[12]

Epidemiology

All the cases of gingivitis do not progress into cases of periodontitis as it depends on the host response.[4] Periodontitis can be broadly classified into chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Cases of chronic periodontitis (CP) are associated with a plethora of plaque and calculus.[13] While the characteristic feature of aggressive periodontitis (AgP) is the familial aggregation of disease, increased amount of periodontal destruction with minimal local factors.[14] AgP further classifies as local aggressive periodontitis (LAP) and generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAP). According to an epidemiological study conducted by Susin et al., the prevalence of LAP depends on the difference in ethnicity and geographic location.[15] It is estimated to be 2.6% in African Americans, 1 to 5% in Africans, 0.2% in Asians, 0.5 to 1% in North Americans, while 0.3 to 2% in South Americans.[15] In an overall perspective, GAP has a prevalence of 0.13%, and LAP has that of less than 1%.[15] In developing countries, there is an increased prevalence of chronic periodontitis as compared to developed countries.[16] According to The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III), 50% of the adult population in the United States of America suffered from gingival and periodontal disease.[17]

Pathophysiology

To understand the pathophysiology of periodontal disease, it is essential to know about the complex dental biofilm as well as the Immune response associated with the disease.

Dental plaque is a complex biofilm, which is the colonization of bacteria enclosed by a protective matrix. This matrix is composed of extracellular polysaccharide and glycoproteins providing a protective environment for microbes in the dental biofilm.[18] This component of the dental biofilm makes it 1000 to 1500 times more resistant to antimicrobial agents.[2] The various circulatory channels present in the biofilm aid in the distribution of many nutrients and excretion of the generated metabolic wastes. "Quorum sensing" is a mode of communication between the microcolonies of bacteria within the dental biofilm.[19] "Autoinducers" are molecules secreted by microbes; the concentration of these molecules helps in regulating bacterial gene expression.[19] The biofilm, by different pH concentrations and metabolites, has various microenvironments within the biofilm. These microenvironments make the ecosystem suitable for a variety of microbes inhabiting in the same dental plaque.[18]

The initial layer deposited on the surface of teeth in the formation of dental plaque is "acquired pellicle."[20] This layer is formed within seconds of the exposure of tooth surfaces, followed by the initial attachment of the early colonizers of the biofilm. Streptococcus and Actinomyces species are the primary colonizers which are gram-positive, facultative bacteria.[20] The "adhesin receptors" present on the surface of primary colonizers bind with the proline-rich proteins of the pellicle. This binding leads to revealing of receptor sites known as "cryptitope" which further leads to coaggregation.[21] Gradually there is a layer by layer deposition of dental plaque leading to a deficiency of oxygen in the environment eventually leading to colonization of anaerobic bacteria.[22] The bridging microbe between primary and secondary colonizers is Fusobacterium species.[22] The gradual shift of these aerobic conditions to anaerobic condition marks the progression of gingivitis to periodontitis. Socransky et al. in a study divided the microbes into microbial complexes based on colors.[23][5] Red and orange complexes bacteria present in the subgingival area are intricately associated with periodontal disease.[5]

Gradually the host as a response to the bacterial infection by classic innate immune response.[24] The response includes signs of acute inflammation including increased redness of gingiva, bleeding and swollen gums as well migration of neutrophils to the site of inflammation. The innate immunity also activates the primary host cells of the body, preparing the body for defense against bacterial infection as well as triggers the adaptive immunity.[24] The Innate immunity also triggers the host cell to differentiate into more specific cells, in turn, increasing the pro-inflammatory mediators like Interleukin 1-beta, prostaglandins and tumor necrosis factor.[24] The cascade gets activated resulting in adaptive immunity getting into pace by activating specific T and B lymphocytes. There is documentation of the role of B and T cell involvement with activation of RANK (Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB) which results in bone loss due to the activation of osteoclasts.[25]

Histopathology

Gingivitis is the initial stage of the response of the body towards local factors present in the oral cavity; this is a reversible process without the loss of any bone or periodontal support.[11][12] Histopathologically, within the lamina propria collagen fibers are destroyed and leading to ulcerations in the sulcular epithelium.[26] According to Page et al., there are three histopathological stages of gingivitis, i.e., initial lesion, early lesion, and established lesion.[26] These lesions are marked by different cells demarcating the transition between these stages. Further inflammatory changes in the gingiva lead to the establishment of periodontal disease by the transition of the established stage to the advanced stage.[26] The spread of inflammation from epithelium to connective tissue takes place laterally and apically resulting in the destruction of collagen fibers. This destruction of collagen fibers presents clinically as "attachment loss" marking the shift from gingivitis to periodontitis. Gradually due to the activation of osteoclast cells, bone resorption is initiated leading to gradual tooth loss.[26]

History and Physical

Periodontal disease has been described as an inflammatory condition by the Chinese and Egyptians as early as 4000 years ago.[27] Hippocrates described the periodontal disease as "the gums were bleeding or rotten" and also enumerated the etiological factors and pathogenesis of various forms of gum disease.[27] Pierre Fauchard was the first to discuss the etiology and treatment modalities by his meticulous research in Le chirurgien dentiste.[28] He gave various treatment modalities for the treatment of periodontitis like scaling and root planning, use of mouthwashes and dentifrices.[28]

Chronic periodontitis is more prevalent in the adult population but can occur in younger patients too.[29] The amount of disease progression correlates to the number of local factors present.[30] The progression of chronic periodontitis is on a slower pace associated with specific microbial bacteria. Familial aggregation and defect in neutrophils are not associated with chronic periodontitis.[30] Generalised signs of gingival inflammation are present, with periodontal pockets ranging from 4 to 12 mm.[30] Clinical features like attachment loss and gingival bleeding are associated with the disease are ignored by the patient due to the painless nature of symptoms. One of the main characteristic nature of the disease is its symptomless feature.[29]

As compared to chronic periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis has a marked group of characteristics that defines the disease very well making it simple to diagnose it. Baer et al. 1971, defined aggressive periodontitis as "a disease of the periodontium occurring in otherwise healthy adolescent, which is characterized by a rapid loss of alveolar bone around more than one tooth of the permanent dentition."[31] The presence of local factors like calculus is not commensurate with the amount of periodontal tissue destruction.[31] The classical case presentation of aggressive periodontitis includes early age onset of disease, vertical bone loss in molars and incisor teeth leading to mobility, familial aggregation, rapid progression of the disease.[14] Aggressive periodontitis subclassifies into localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP) and generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAP). LAP is characterized by bone loss including permanent molars and incisors while GAP involved most of the permanent teeth.[14]

Evaluation

For cases of chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis, both clinical, as well as radiographic examination, is mandatory. Clinical examination involves estimation of local factors, developmental discrepancies of teeth leading to increased plaque accumulation, bleeding on probing (a sign of inflammation of periodontal tissue), periodontal probing pocket depth estimation is done manually or using pressure sensitive probes, determination of furcation involvement, recession, determination of clinical attachment level.[32] Followed by clinical examination radiographic estimation of bone loss should be done using a set of intraoral periapical radiographs, bitewing radiographs or a panoramic radiograph.[32]

In cases of aggressive periodontitis, the classical clinical features along with radiographic evaluation help in diagnosis.[14] In an oral pantomograph, mirror-like arch defects seen in the permanent molar region.[14] Periodontal pathogens including Aggregatibacter, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tanerella forsythia, and Campylobacter rectus are associated with periodontitis in various microbiological, epidemiological studies.[33][2]

Treatment / Management

The main aim of periodontal therapy is to improve the gingival health of the patient and preserve the remaining periodontal tissues.[34] Both local factors, as well as the bacterial load of periodontopathogens, require reduction along with the correction of behavioral factors such as cessation of smoking and tobacco consumption is a part of periodontal treatment.[34]

After the clinical and radiographic assessment of the patient, Periodontal charting is done along with the recording of periodontal indices to gauge the severity and extent of disease. Following the clinical assessment, the patient should receive counsel to initiate behavioral changes like cessation of smoking and motivation to improve oral hygiene measures.[35] Followed by evaluation, non-surgical periodontal therapy commences, which includes scaling and root planning, mouthwashes, and dentrifices, local drug delivery at the infection site, systemic chemotherapeutic agents as an adjunct to scaling, and root planning.[36] Regular review of non-surgical periodontal therapy is critical as non-responding sites have to be treated by surgical periodontal therapy followed by a periodontal maintenance phase.[34]

Differential Diagnosis

Periodontal disease may depict as gingival or periodontal abscess, acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, endodontic-periodontal lesions.[37] In cases of localized periodontal disease, the origin of the disease requires differentiation between pulpal and periodontal origin. Non-responding cases of periodontitis categorize as refractory periodontitis.[37]

Prognosis

Several factors affect the prognosis of periodontally involved teeth.

Factors like the position of teeth in the arch also affect the prognosis of teeth having periodontitis, like the risk of mandibular canine is least while the maxillary second molar is the highest.[38] Prognosis is poor for teeth with increased periodontal probing pocket depth, mobility, bone loss, furcation involvement, malpositioned teeth, and an inadequate crown-root ratio.[39] With the improving effectiveness of oral hygiene measure practiced by the patient and discontinuation of smoking, the prognosis of the case improves along with decreasing mobility of the teeth.[39] Teeth with bleeding sites during the maintenance phase have a risk of attachment loss three times more as compared to non-bleeding sites.[40]

Complications

An inflammatory host response characterizes periodontal disease. The surface of periodontal tissue affected by inflammatory changes is about 15 cm^2 to 72 cm^2.[41] The inflammatory burden present due to untreated periodontal disease is associated with not only local destruction of periodontal tissue but due to an increase in C-reactive protein causes systemic effects on the cardiovascular system, low term birth weight in newborn babies, Type II diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[42]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The most critical factor which determines the shift of periodontal disease to health is the establishment of effective oral hygiene measures.[43] The demonstration of brushing techniques like the Bass brushing technique should be shown on models and the patient's mouth as well as by video demonstrations along with the importance of interdental brushing.[34] This particular stage of patient compliance plays a pivotal role in the success of the treatment and long term maintenance of periodontal health.[43] Periodontal disease management is drastically affected by the cessation of smoking.[35] The periodontal maintenance phase with repeated reinforcement of oral hygiene techniques in a patient-tailored recall programme helps in improving the prognosis of the disease.[44]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Periodontitis is the most common disease associated with the oral cavity. Approximately 50 % of the patients visiting a dental clinic are suffering from gingival or periodontal disease. It is imperative for the clinician to identify the periodontal disease and address the problem with appropriate treatment modalities. The final complication in cases of periodontitis is not limited to tooth loss, but it also affects the general systemic health of the patient. Hence it is crucial for just not the dentist but also for the general physicians to be aware of the ill effects of periodontitis on systemic health.[45] (Level I) In cases of periodontal involvement there are chances of pulpal involvement of the tooth, hence other specialties of dentistry including the dental nurse also need to be involved for appropriate care.

The treatment requires a holistic approach. The treatment involves the patient's motivation as well as a local intervention using non-surgical and surgical periodontal treatment along with the adjunctive role of chemotherapeutic agents.[46]The most important part is the maintenance phase of periodontal treatment, which plays a crucial role in the prevention of the disease from reoccurring.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005 Nov:43(11):5721-32 [PubMed PMID: 16272510]

Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2012 Oct:10(10):717-25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2873. Epub 2012 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 22941505]

Petersen PE, Baehni PC. Periodontal health and global public health. Periodontology 2000. 2012 Oct:60(1):7-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00452.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22909103]

Bartold PM, Van Dyke TE. Periodontitis: a host-mediated disruption of microbial homeostasis. Unlearning learned concepts. Periodontology 2000. 2013 Jun:62(1):203-17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00450.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23574467]

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1998 Feb:25(2):134-44 [PubMed PMID: 9495612]

Darveau RP. Periodontitis: a polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2010 Jul:8(7):481-90. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2337. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20514045]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim J, Amar S. Periodontal disease and systemic conditions: a bidirectional relationship. Odontology. 2006 Sep:94(1):10-21 [PubMed PMID: 16998613]

Lamont RJ, Hajishengallis G. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis in inflammatory disease. Trends in molecular medicine. 2015 Mar:21(3):172-83. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.004. Epub 2014 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 25498392]

Shi B, Chang M, Martin J, Mitreva M, Lux R, Klokkevold P, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Haake SK, Li H. Dynamic changes in the subgingival microbiome and their potential for diagnosis and prognosis of periodontitis. mBio. 2015 Feb 17:6(1):e01926-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01926-14. Epub 2015 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 25691586]

Bergström J. Tobacco smoking and chronic destructive periodontal disease. Odontology. 2004 Sep:92(1):1-8 [PubMed PMID: 15490298]

LOE H, THEILADE E, JENSEN SB. EXPERIMENTAL GINGIVITIS IN MAN. The Journal of periodontology. 1965 May-Jun:36():177-87 [PubMed PMID: 14296927]

Theilade E, Wright WH, Jensen SB, Löe H. Experimental gingivitis in man. II. A longitudinal clinical and bacteriological investigation. Journal of periodontal research. 1966:1():1-13 [PubMed PMID: 4224181]

Armitage GC, Cullinan MP. Comparison of the clinical features of chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Periodontology 2000. 2010 Jun:53():12-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00353.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20403102]

Albandar JM. Aggressive periodontitis: case definition and diagnostic criteria. Periodontology 2000. 2014 Jun:65(1):13-26. doi: 10.1111/prd.12014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24738584]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSusin C, Haas AN, Albandar JM. Epidemiology and demographics of aggressive periodontitis. Periodontology 2000. 2014 Jun:65(1):27-45. doi: 10.1111/prd.12019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24738585]

Ababneh KT, Abu Hwaij ZM, Khader YS. Prevalence and risk indicators of gingivitis and periodontitis in a multi-centre study in North Jordan: a cross sectional study. BMC oral health. 2012 Jan 3:12():1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-12-1. Epub 2012 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 22214223]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlbandar JM, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Destructive periodontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988-1994. Journal of periodontology. 1999 Jan:70(1):13-29 [PubMed PMID: 10052767]

Hillman JD, Socransky SS, Shivers M. The relationships between streptococcal species and periodontopathic bacteria in human dental plaque. Archives of oral biology. 1985:30(11-12):791-5 [PubMed PMID: 3868968]

Plančak D, Musić L, Puhar I. Quorum Sensing of Periodontal Pathogens. Acta stomatologica Croatica. 2015 Sep:49(3):234-41. doi: 10.15644/asc49/3/6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27688408]

Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community - implications for health and disease. BMC oral health. 2006 Jun 15:6 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S14 [PubMed PMID: 16934115]

Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a microbial biofilm. Caries research. 2004 May-Jun:38(3):204-11 [PubMed PMID: 15153690]

Jenkinson HF, Lamont RJ. Oral microbial communities in sickness and in health. Trends in microbiology. 2005 Dec:13(12):589-95 [PubMed PMID: 16214341]

SOCRANSKY SS, GIBBONS RJ, DALE AC, BORTNICK L, ROSENTHAL E, MACDONALD JB. The microbiota of the gingival crevice area of man. I. Total microscopic and viable counts and counts of specific organisms. Archives of oral biology. 1963 May-Jun:8():275-80 [PubMed PMID: 13989807]

Silva N, Abusleme L, Bravo D, Dutzan N, Garcia-Sesnich J, Vernal R, Hernández M, Gamonal J. Host response mechanisms in periodontal diseases. Journal of applied oral science : revista FOB. 2015 May-Jun:23(3):329-55. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720140259. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26221929]

Hajishengallis G, Lambris JD. Microbial manipulation of receptor crosstalk in innate immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2011 Mar:11(3):187-200. doi: 10.1038/nri2918. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21350579]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePage RC, Schroeder HE. Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1976 Mar:34(3):235-49 [PubMed PMID: 765622]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMitsis FJ. Hippocrates in the golden age: his life, his work and his contributions to dentistry. The Journal of the American College of Dentists. 1991 Spring:58(1):26-30 [PubMed PMID: 2066507]

. [Pierre Fauchard's Le Chirurgien-Dentiste]. Dental Cadmos. 1980 May:48(5):57-60 contd [PubMed PMID: 7004919]

Loesche WJ, Grossman NS. Periodontal disease as a specific, albeit chronic, infection: diagnosis and treatment. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2001 Oct:14(4):727-52, table of contents [PubMed PMID: 11585783]

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Smith C, Dibart S. Relation of counts of microbial species to clinical status at the sampled site. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1991 Nov:18(10):766-75 [PubMed PMID: 1661305]

Baer PN. The case for periodontosis as a clinical entity. Journal of periodontology. 1971 Aug:42(8):516-20 [PubMed PMID: 5284178]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePreshaw PM. Detection and diagnosis of periodontal conditions amenable to prevention. BMC oral health. 2015:15 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-15-S1-S5. Epub 2015 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 26390822]

Carrouel F, Viennot S, Santamaria J, Veber P, Bourgeois D. Quantitative Molecular Detection of 19 Major Pathogens in the Interdental Biofilm of Periodontally Healthy Young Adults. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016:7():840. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00840. Epub 2016 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 27313576]

Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. Treatment of plaque-induced gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, and other clinical conditions. Journal of periodontology. 2001 Dec:72(12):1790-800 [PubMed PMID: 11811516]

Preshaw PM, Heasman L, Stacey F, Steen N, McCracken GI, Heasman PA. The effect of quitting smoking on chronic periodontitis. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2005 Aug:32(8):869-79 [PubMed PMID: 15998271]

Walker CB. The acquisition of antibiotic resistance in the periodontal microflora. Periodontology 2000. 1996 Feb:10():79-88 [PubMed PMID: 9567938]

Ramachandra SS, Gupta VV, Mehta DS, Gundavarapu KC, Luigi N. Differential Diagnosis between Chronic versus Aggressive Periodontitis and Staging of Aggressive Periodontitis: A Cross-sectional Study. Contemporary clinical dentistry. 2017 Oct-Dec:8(4):594-603. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_623_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29326511]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcFall WT Jr. Tooth loss in 100 treated patients with periodontal disease. A long-term study. Journal of periodontology. 1982 Sep:53(9):539-49 [PubMed PMID: 6957591]

McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. II. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in developing an accurate prognosis. Journal of periodontology. 1996 Jul:67(7):658-65 [PubMed PMID: 8832476]

Lang NP, Joss A, Orsanic T, Gusberti FA, Siegrist BE. Bleeding on probing. A predictor for the progression of periodontal disease? Journal of clinical periodontology. 1986 Jul:13(6):590-6 [PubMed PMID: 3489010]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePage RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, Seymour GJ, Kornman KS. Advances in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: summary of developments, clinical implications and future directions. Periodontology 2000. 1997 Jun:14():216-48 [PubMed PMID: 9567973]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBeck JD, Slade G, Offenbacher S. Oral disease, cardiovascular disease and systemic inflammation. Periodontology 2000. 2000 Jun:23():110-20 [PubMed PMID: 11276757]

Axelsson P, Nyström B, Lindhe J. The long-term effect of a plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults. Results after 30 years of maintenance. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2004 Sep:31(9):749-57 [PubMed PMID: 15312097]

Axelsson P, Lindhe J. The significance of maintenance care in the treatment of periodontal disease. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1981 Aug:8(4):281-94 [PubMed PMID: 6947992]

Linden GJ, Herzberg MC, Working group 4 of joint EFP/AAP workshop. Periodontitis and systemic diseases: a record of discussions of working group 4 of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2013 Apr:40 Suppl 14():S20-3. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12091. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23627330]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeitz-Mayfield LJ, Trombelli L, Heitz F, Needleman I, Moles D. A systematic review of the effect of surgical debridement vs non-surgical debridement for the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2002:29 Suppl 3():92-102; discussion 160-2 [PubMed PMID: 12787211]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence