Introduction

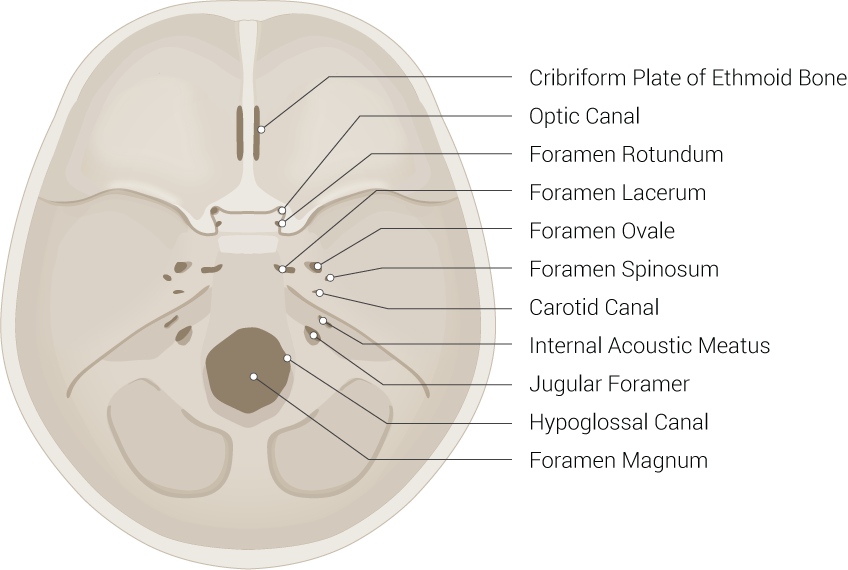

The existence of multiple foramina in the base of the skull permits the passing of crucial vital tissues, most importantly, blood vessels and nerves which pass from the head to the body and vice versa. Foramen lacerum is an irregular opening located in the middle cranial fossa at the base of the skull. It is covered by cartilage after birth. It is formed by the apex of the petrous temporal bone and allows the passing of the internal carotid artery, the deep petrosal nerve which arises from the carotid plexus that surrounds the internal carotid artery, and greater petrosal nerve.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The foramen lacerum is in the middle aspect of the petrous temporal bone, between the central part of the body of the sphenoid anteriorly, the basilar part of the occipital bone medially, and the carotid canal. This location allows the passing of the internal carotid artery to the foramen lacerum then to the cavernous sinus to supply the brain parenchyma and the eye posterolaterally.[1]

The deep petrosal nerve and the greater petrosal nerve meet in the foramen lacerum to form the Vidian nerve, which is composed of the fusion of the deep petrosal nerve and great petrosal nerve in the pterygoid canal.

The pterygoid canal is an opening that extends from the bony part of the lacerum anteriorly, to reach the pterygopalatine fossa.

The vidian nerve carries parasympathetic and sympathetic fibers to the pterygopalatine ganglion, which is in the pterygopalatine fossa. The parasympathetic fibers are the contribution of the greater petrosal nerve, and the sympathetic fibers are the contribution of the deep petrosal nerve which originates in the foramen lacerum from the carotid plexus.

Pterygopalatine fossa which contains the pterygopalatine ganglion is located inferior to the posterior part of the inferior orbital fissure, behind the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, and antero-inferiorly to the middle cranial fossa.[1][2][3]

The internal carotid artery (ICA), passes from the carotid canal to the foramen lacerum. In the lacerum, postganglionic sympathetic fibers ascend along with the internal carotid artery known as the deep petrosal nerve connect to the greater petrosal nerve gives the Vidian nerve or nerve to the pterygoid canal.[1]

Embryology

The petrous part of the temporal bone along with the occipital bone derives from the paraxial mesoderm. Both develop from endochondral ossification which starts developing from a mesenchyme layer which condensed into cartilage then ossify.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The internal carotid artery, which begins at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery at the upper border of thyroid cartilage supplies the eyes, forehead, part of the nose, and mainly the brain. The internal carotid artery enters the cranial cavity and leaves the neck by the carotid canal in the petrous temporal bone; then it bends to enter the cartilaginous lacerum foramina. In the lacerum, it gives of the deep petrosal nerve. After giving off the deep petrosal nerve, it continues vertically, forward to enter the cavernous sinus. Eventually, it leaves the cavernous sinus medial to the anterior clinoid process of the sphenoid bone to give its terminal branches, the anterior and middle cerebral arteries, and the posterior communicating artery.[1]

Nerves

The two nerves that pass from the foramen lacerum are the greater petrosal nerve, which represents the pre-ganglionic parasympathetic fibers, and the deep petrosal nerve which, representing the post-ganglionic sympathetic fibers. Both of these nerves form the autonomic fibers of the facial nerve and supply the submandibular, sublingual, salivary, nasal, and palatine glands.

Pre-ganglionic para-sympathetic fibers originate from the superior salivatory nucleus in the pons. Then it passes to the internal auditory canal along with the nervus intermedius of the facial nerve. Both of them transport to the geniculate ganglion. The greater petrosal nerve (GPN) arises from the geniculate ganglion then passes vertically to the floor of the middle cranial fossa via the hiatus of the greater petrosal nerve. In the middle cranial fossa, the greater petrosal nerve passes medially to enter the foramen lacerum and fuses there with the deep petrosal nerve, forming the Vidian nerve or pterygoid nerve, which passes from the pterygoid canal to the pterygopalatine fossa (PPF). Then para-sympathetic fibers of the Vidian nerve synapse within the pterygopalatine fossa to supply the lacrimal, buccal, nasopharynx, and nasal glands.

Preganglionic sympathetic fibers originate from the intermediate horn of the spinal gray matter of the spinal cord of T1. Then ascend to the cervical sympathetic trunk, which eventually lays on the superior cervical ganglion to synapse with postganglionic neurons. Post-ganglionic sympathetic fibers ascend along with the internal carotid artery. It enters the skull from the carotid canal then to the foramen lacerum where it gives the deep petrosal nerve (DPN). The deep petrosal nerve then fuses with the greater petrosal nerve to form the Vidian nerve, which passes through the pterygoid canal to the pterygopalatine fossa. These post-ganglionic sympathetic fibers do not synapse with the pterygopalatine ganglion and supply the secretomotor elements of lacrimal glands and nasal mucosa.[1][2][5][6][7]

Surgical Considerations

Anatomical variations of the pterygoid canal are very significant for surgeons who usually take an inferior medial approach to the pterygoid canal during Vidian neurectomy, while in some patients the pterygoid canal is located above the level of the anterior genu of the petrous part of the internal carotid artery.[8]

Clinical Significance

Iatrogenic or traumatic injury to the neck may cause damage to the internal carotid artery or even the sympathetic plexus around it, causing damage to the deep petrosal nerve, which also can be damaged by neck surgery, sphenoidal surgery, or even Vidian neurectomy.[9]

Atheroma or emboli dislodged from the heart in the internal carotid artery may cause visual impairment or in more severe cases blindness, due to either lack of blood flow in the retinal artery or complete blockage.[2]

Cluster headache is characterized by unilateral recurrent attacks of severe headache, accompanied by severe pain around the eye and involvement of the deep petrosal nerve and the great petrosal nerve which leads to rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, and excessive lacrimation. Vidian neurectomy is a procedure to remove the Vidian nerve; it is considered as one of the possible treatments in cluster headache, to decrease lacrimation and rhinitis.[10][11]

Crocodile tear syndrome, characterized by excessive tearing unilateral or bilateral after exposure to taste or smell stimuli, instead of increased salivation. It happens due to misdirected stimulation to the lacrimal gland instead of the submandibular gland during the recovery period after facial nerve injury. The result of excessive lacrimal gland stimulation by the great petrosal nerve is an ipsilateral tearing of the eyes, instead of increased salivation.[6][12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Khonsary SA, Ma Q, Villablanca P, Emerson J, Malkasian D. Clinical functional anatomy of the pterygopalatine ganglion, cephalgia and related dysautonomias: A review. Surgical neurology international. 2013:4(Suppl 6):S422-8. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.121628. Epub 2013 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 24349865]

Cappello ZJ, Potts KL. Anatomy, Pterygopalatine Fossa. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020641]

Budu V, Mogoantă CA, Fănuţă B, Bulescu I. The anatomical relations of the sphenoid sinus and their implications in sphenoid endoscopic surgery. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2013:54(1):13-6 [PubMed PMID: 23529304]

Singh O, M Das J. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Jugular Foramen. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860742]

Tepper SJ, Caparso A. Sphenopalatine Ganglion (SPG): Stimulation Mechanism, Safety, and Efficacy. Headache. 2017 Apr:57 Suppl 1():14-28. doi: 10.1111/head.13035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28387016]

Modi P, Arsiwalla T. Crocodile Tears Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30247828]

Dulak D, Naqvi IA. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 7 (Facial). StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252375]

Adin ME, Ozmen CA, Aygun N. Utility of the Vidian Canal in Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery: Detailed Anatomy and Relationship to the Internal Carotid Artery. World neurosurgery. 2019 Jan:121():e140-e146. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.048. Epub 2018 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 30240854]

Chen J, Xiao J. Morphological study of the pterygoid canal with high-resolution CT. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2015:8(6):9484-90 [PubMed PMID: 26309612]

Waldenlind E, Sjöstrand C. Pathophysiology of cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2010:97():389-411. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(10)97033-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20816439]

Nappi G, Moskowitz MA. Cluster headache and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias general aspects. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2010:97():387-8. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(10)97032-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20816438]

Spiers AS. Syndrome of "crocodile tears". Pharmacological study of a bilateral case. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1970 May:54(5):330-4 [PubMed PMID: 5428665]