Introduction

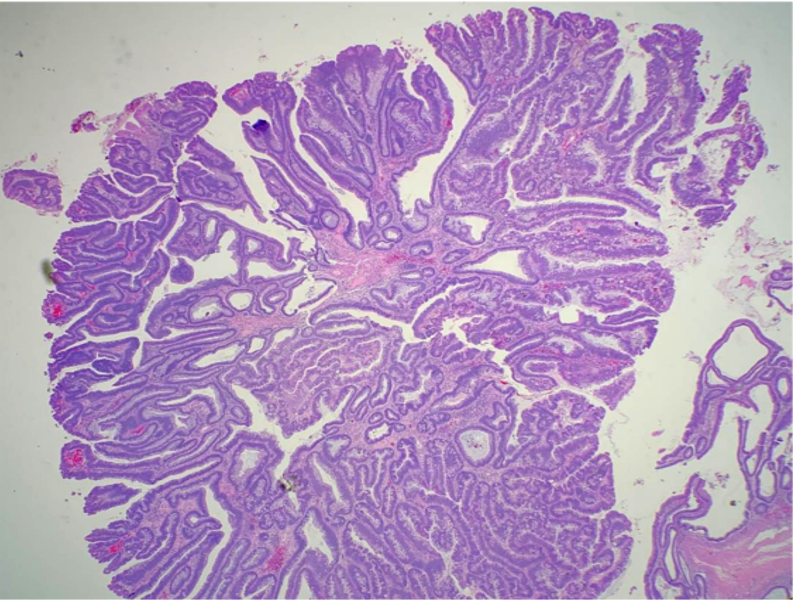

Adenoma refers broadly to any benign tumor of glandular tissue. This activity addresses specifically adenomas of the colon, occurring within polyps. Colon polyps are a common entity, increasing in prevalence with age. Adenomatous polyps are the most common type of polyp in the colon, accounting for about 60 to 70% of all colonic polyps. Conventional-type adenomatous polyps can be classified as tubular, villous, or tubulovillous. More than 75% of villous features characterize villous adenomas, whereas villous refers to finger-like or leaf-like epithelial projections (see Image. Villous Adenoma). Tubulovillous adenomas have between 25 and 75% villous features. Less than 25% of villous features indicate a tubular adenoma. Adenomas are usually asymptomatic and found on routine colorectal cancer screening. Adenomas with villous features may be associated with a slight increase in the development of more advanced neoplasia or dysplasia compared to other adenomas.[1][2][3] Villous adenomas occur more frequently in the rectosigmoid area but can occur elsewhere in the colon.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The risk of developing colorectal polyps is related to environmental and genetic factors. The majority of polyps in the colon arise sporadically, even though genetics play the most important role in influencing the individual risk of developing colon polyps and subsequent colorectal cancer. Personal history of colon adenomas places a patient at increased risk for the future development of colon cancer.[4][5][6] Colorectal cancer has been shown to arise mainly from pre-existing adenomatous colon polyps. Adenomatous polyps form, as mentioned above, primarily in a sporadic fashion. The sporadic nature of these polyps results from either a mutation in the adenomatous coli pathway or DNA mismatch repair.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a genetic disorder that, in particular, predisposes affected patients to the development of multiple adenomatous polyps. FAP is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by a mutation in the tumor suppressor APC gene located on chromosome 5q. This mutation can either be inherited or present as a new germline mutation in as many as 1 out of 3 patients. The frequency of FAP is from 1 in 8,000 to 1 in 14,000, with large numbers of adenomas occurring beginning in late childhood. Classically, patients with FAP have over 100 colorectal adenomatous polyps, but many patients have several hundred or even thousands of polyps. These patients usually develop adenocarcinoma by the age of 30 to 40. Even given the likely development of colon cancer in these patients, FAP only accounts for around 1% of colon cancers.

Adenomas are defined as possessing at least the characteristics of low-grade dysplasia. Some adenomas may progress over an extended period from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or invasive adenocarcinoma. Although physicians debate this, and the evidence does not completely confirm, thus far, if villous features indicate an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer, multiple studies demonstrate that histologic villous features of adenomas may be associated with developing advanced forms of neoplasia. Size at baseline of adenomas has been shown in some studies to influence future advanced disease; lesions greater than 1 cm increase a patient's risk. One source states that villous lesions have an increased risk of containing adenocarcinoma correlated to size specifically, with a 10% to 20% risk in adenomas larger than 2 cm and a 5% risk in adenomas from 1 cm to 2 cm in size. However, these findings are inconsistent across multiple studies regarding the subject. A recent study proposes using the overall sum of all adenoma diameters (called the adenoma bulk) at initial surveillance colonoscopy to stratify patients as either high or low-risk for predicting the development of advanced neoplasia. This study states that the adenoma bulk is comparatively predictive as the conventional current model uses histology features when using a risk stratification cutoff of 10mm for the adenoma bulk, with high-risk adenoma bulk greater than or equal to 10 mm.[4][5][6] \

Risk factors for villous adenoma include the following:

- Lifestyle and diet. Vegetables and fruits are known to protect against adenomas, whereas fat and alcohol consumption increase the risk.

- There is a strong association between tobacco and adenoma development.

- Patients with acromegaly are at high risk for adenomas and colon cancer.

- Past studies indicate an association between Streptococcus bovis and rectal villous adenoma formation.

- Patients who have undergone a urinary diversion procedure are also at high risk for developing adenomas.

- Patients with Inflammatory bowel disease are also at high risk for adenomas and colorectal cancer.

Epidemiology

The incidence of colon polyps increases in direct correlation with age. By age 50, colorectal cancer screening studies have demonstrated a prevalence of 25% to 30%, increasing to 50% by age 70 in high-risk Western countries such as the United States. Colon polyps are rare in the younger population, present in only 1 to 4 percent of 20 to 30-year-olds. Villous adenomas account for 5% to 15% of all adenomas.[7][8]

Histopathology

Before discussing what constitutes villous features of adenomas, it is important to differentiate the degree of dysplasia present in adenomas. The degree of dysplasia present in an adenoma is determined by both cytological and architectural features. Adenomas are tumors of dysplastic epithelium, which can be characterized as having low-grade or high-grade dysplasia, which indicates the epithelium's maturation level. By definition, adenomas have at least low-grade dysplasia. The cytological features of low-grade dysplasia include crowded, pseudo-stratification to early stratification of spindled or elongated nuclei occupying the cytoplasm's basal half. Pleomorphism and atypical mitoses should be absent or minimally present. Mitotic activity and minimal loss of cell polarity are allowed. Architecturally, the crypts should resemble the normal colon without significant crowding, cribriform, or complex forms.

High-grade dysplasia cytologically shows an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, more significant loss of polarity, and more "open" appearing nuclei with increasingly prominent nucleoli. Other features that distinguish a high-grade from low-grade dysplasia include significant pleomorphism, rounded nuclei, atypical mitoses, and significant loss of polarity. Mitotic figures may be observed in low-grade dysplasia. Cribriform and crowding, back-to-back glands indicate high-grade dysplasia. They can be important architectural features to aid in differentiating some cases of low vs high-grade dysplasia, which may have less distinct cytological features. The villous component of adenomas refers to epithelial finger-like projections away from the muscularis mucosae. There should be deep crypts, and the projections should contain fibrovascular cores lined by dysplastic epithelium. As stated above, the amount of villous differentiation distinguishes villous adenomas (over 75% villous features) from tubulovillous adenomas (mixed tubular and villous features with 25% to 75% villous features).

History and Physical

Most patients do not present symptomatically and subsequently have a colonoscopy identifying colorectal polyps. Rather, polyps are found on screening or surveillance colonoscopies. If patients do present with symptoms, they commonly endorse a history of blood per rectum. Polyps greater than 1 cm are more likely to cause symptoms like abdominal cramps, changes in bowel habits, and rectal bleeding. Rarely, a villous adenoma may induce secretory diarrhea, resulting in dehydration and electrolyte deficiency.

Evaluation

The current US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation for average-risk adults is that beginning at age 50, patients should initiate regular colon cancer screening. Methods include a fecal occult blood test, fecal immunochemical test, and direct visualization methods. Direct visualization through colonoscopy, biopsy, and histologic examination of colon lesions is necessary to examine and diagnose colorectal polyps and cancers. Blood work may reveal low hemoglobin and mean cell volume, indicating iron deficiency anemia. These patients also have low serum iron and ferritin levels. Only about 40% of patients with villous adenoma have a positive fecal occult blood test. Of these, about 2-10% may harbor colon cancer.

Double-contrast barium enema has better sensitivity compared to single contrast barium study. But barium enema is not sensitive when the polyp is less than 6 mm in diameter. In addition, poor bowel preparation can result in false positives. The presence of diverticular disease can lead to false negatives. CT colonography is a novel method to assess the bowel, but it still requires proper bowel preparation. Again, it is not sensitive to polyps less than 6 mm in diameter. Endoscopy is the most sensitive method for assessing the presence of polyps and allows for therapeutic intervention. While colonoscopy is better than other methods for evaluating polyps, it is also very operator-dependent. Difficulties with colonoscopy include patient discomfort and the risk of perforation, especially when a polyp is excised. Sigmoidoscopy only allows visualization of the bowel to 60 cm, and patients often do not require full bowel preparation.

Treatment / Management

Surgeons should completely excise adenomatous polyps of any type and confirm clear margins.[9][10][11] Based on the morphology and the number of lesions removed, surveillance guidelines according to the American Cancer Society are as follows:

- Average risk (no first-degree relative to colon cancer): Colonoscopy at age 50.

- No adenoma or carcinoma; repeat in 10 years.

- One to 2 small (no more than 1 cm) tubular adenomas with low-grade dysplasia, repeat in 5 to 10 years.

- Three to 10 adenomas, a large (at least 1 cm) adenoma, or any adenomas with high-grade dysplasia or villous features, repeat in 3 years.

- More than 10 adenomas on a single exam, repeat within 3 years.

- Increased risk (positive family history in the first-degree relative before age 60, or in 2 or more first-degree relatives at any age if not a hereditary syndrome) Colonoscopy at age 40, or 10 years before the youngest case in the immediate family (whichever is earlier). Repeat the above surveillance guidelines with the caveat that the maximum time between screening should be 5 years.

- High-risk (hereditary colon cancer/polyposis syndromes)

- FAP: Annual flexible sigmoidoscopy; if genetically proven FAP, consider colectomy.

Surgery is necessary if the polyp is more than 2-3 cm, is sessile, and the margins are not clean following a polypectomy.

Differential Diagnosis

Complications for villous adenomas include the following:

- Juvenile polyps

- Cowden disease

- Mucosal prolapse

- Pseudopolyposis

- Lymphoid polyps

Prognosis

While most villous adenomas are asymptomatic, they have the potential to cause obstruction, hemorrhage, and intussusception. However, the major concern with villous adenomas is the development of malignancy. Lesions larger than 1 cm have a high risk for malignancy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing patients with colonic polyps is best done with an interprofessional team. Patients with colonic adenomas may be asymptomatic or present with rectal bleeding. In any patient over the age of 50 with no familial polyposis syndrome, one should always consider the possibility of a malignancy. The primary caregiver should refer these patients to a gastroenterologist or general surgeon for further workup and lesion removal. While most colonic polyps are benign, villous adenomas tend to have a high malignancy rate. Patient education is vital because lifestyle changes may help prevent polyps. The patient should limit the intake of fat and meat products and ingest more vegetables. In addition, patients should consume more fiber and discontinue smoking. Nurses should educate the patient on the maintenance of healthy body weight, regular exercise, and abstaining from alcohol. To ensure good outcomes, the team should communicate with each other and make appropriate referrals on time.

Media

References

Chubak J, McLerran D, Zheng Y, Singal AG, Corley DA, Doria-Rose VP, Doubeni CA, Kamineni A, Haas JS, Halm EA, Skinner CS, Zauber AG, Wernli KJ, Beaber EF, PROSPR consortium. Receipt of Colonoscopy Following Diagnosis of Advanced Adenomas: An Analysis within Integrated Healthcare Delivery Systems. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2019 Jan:28(1):91-98. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0452. Epub 2018 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 30459208]

Jin Y, Yao L, Zhou P, Jin S, Wang X, Tang X, Peng X, Hua P, Ren Y, Gong L. [Risk analysis of the canceration of colorectal large polyps]. Zhonghua wei chang wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2018 Oct 25:21(10):1161-1166 [PubMed PMID: 30370516]

Rezasoltani S, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Dabiri H, Akhavan Sepahi A, Modarressi MH, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E. The association between fecal microbiota and different types of colorectal polyp as precursors of colorectal cancer. Microbial pathogenesis. 2018 Nov:124():244-249. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.08.035. Epub 2018 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 30142468]

Grunwald D, Landau A, Jiang ZG, Liu JJ, Najarian R, Sheth SG. Further Defining the 2012 Multi-Society Task Force Guidelines for Surveillance of High-risk Adenomas: Is a 3-Year Interval Needed for All Patients? Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2019 Oct:53(9):673-679. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001097. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30036239]

Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M, Schoen RE. Association of Colonoscopy Adenoma Findings With Long-term Colorectal Cancer Incidence. JAMA. 2018 May 15:319(19):2021-2031. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5809. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29800214]

Carvalho B, Diosdado B, Terhaar Sive Droste JS, Bolijn AS, Komor MA, de Wit M, Bosch LJW, van Burink M, Dekker E, Kuipers EJ, Coupé VMH, van Grieken NCT, Fijneman RJA, Meijer GA. Evaluation of Cancer-Associated DNA Copy Number Events in Colorectal (Advanced) Adenomas. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2018 Jul:11(7):403-412. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-17-0317. Epub 2018 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 29685877]

Zhou H, Shen Z, Zhao J, Zhou Z, Xu Y. [Distribution characteristics and risk factors of colorectal adenomas]. Zhonghua wei chang wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2018 Jun 25:21(6):678-684 [PubMed PMID: 29968244]

Wong S, Lidums I, Rosty C, Ruszkiewicz A, Parry S, Win AK, Tomita Y, Vatandoust S, Townsend A, Patel D, Hardingham JE, Roder D, Smith E, Drew P, Marker J, Uylaki W, Hewett P, Worthley DL, Symonds E, Young GP, Price TJ, Young JP. Findings in young adults at colonoscopy from a hospital service database audit. BMC gastroenterology. 2017 Apr 19:17(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0612-y. Epub 2017 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 28424049]

Park SK, Yang HJ, Jung YS, Park JH, Sohn CI, Park DI. Risk of advanced colorectal neoplasm by the proposed combined United States and United Kingdom risk stratification guidelines. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2018 Mar:87(3):800-808. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.09.023. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 28986265]

Dessain A, Snauwaert C, Baldin P, Deprez P, Libbrecht L, Piessevaux H, Jouret-Mourin A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection specimens in early colorectal cancer: lateral margins, macroscopic techniques, and possible pitfalls. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 2017 Feb:470(2):165-174. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-2055-1. Epub 2016 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 27933386]

van Heijningen EM, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Hees F, Kuipers EJ, Biermann K, de Koning HJ, van Ballegooijen M, Steyerberg EW, SAP Study Group. Developing a score chart to improve risk stratification of patients with colorectal adenoma. Endoscopy. 2016 Jun:48(6):563-70. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-104275. Epub 2016 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 27167762]