Introduction

Iris tumors are relatively infrequent compared to similar ciliary tumors but comprise a broad spectrum of benign and malignant pathologies. Due to the lack of metastatic potential, benign iris tumors generally offer a more favorable prognosis than malignant lesions. However, even benign iris tumors can threaten vision.

Benign iris tumors can be broadly categorized as either cystic or solid. Cystic lesions tend to be stable over time and exhibit well-defined, predictable behavior. Solid iris tumors encompass a wide range of melanocytic and nonmelanocytic variants.[1] The most commonly encountered malignant iris tumor is melanoma, which has significant metastatic potential.

This activity reviews the epidemiology, etiology, clinical manifestations, evaluation methods, histopathology, treatment modalities, and prognosis of iris tumors. Categorizing these tumors by origin, such as melanomas, adenocarcinomas, metastases, and benign neoplasms, permits a tailored approach to each tumor subtype.

The iris tumor variants discussed in this article include:

Malignant Lesions

- Metastases to the iris

- Iris melanoma

- Iris pigment epithelium adenocarcinoma

Benign Lesions

- Iris cysts

- Iris nevus

- Iris pigment epithelium adenoma

- Iris leiomyoma

- Iridic nodules

- Vascular tumors of the iris.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the iris

Metastatic iridic lesions primarily originate from breast or lung carcinomas, accounting for 37% and 27% of iris metastases, respectively. Other frequent primary sites include the kidney (8%), the gastrointestinal tract (8%), and the prostate (2%).[1][2]

Iris melanoma

Most iris melanomas are composed of spindle cells. BAP1 is a major tumor suppressor, and germline BAP1 mutations predispose to uveal melanoma and other malignancies.[3] More than 75% of iris melanomas originate in the inferior half of the iris.[4] While the role of UV exposure in developing iris melanoma remains unclear, data strongly suggests a synergistic risk between light-colored irises, UV exposure, and uveal melanoma.[4] Uveal melanomas have a 30% greater incidence in male patients, although the incidence varies with geographic location. In the United States, the incidence is highest in non-Hispanic White people, with an estimated rate of 6.02 per million. The incidence of iris melanoma also increased with increasing latitude in Europe.[5]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma and adenocarcinoma

Iris adenomatous proliferations are of neuroectodermal origin, differentiating them from melanomatous proliferations with neural crest origins.[6]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

Iris cysts may be primary or secondary. Primary iris cysts are composed of iris stroma or pigment epithelium. Secondary iris cysts result from external factors including but not limited to trauma, parasitic infection, or iatrogenic injury. Distinguishing cysts from other lesions of the iris is challenging because of the vast number of etiologic possibilities.[1]

Iris nevus

Iridic nevi are of melanocytic origin and are often considered precursor lesions to malignant melanoma. A retrospective study of 1611 patients with an iris nevus revealed a 15-year conversion rate to melanoma of 8%.[7]

Iris leiomyoma

Iris leiomyomas are incredibly rare ocular lesions. Improved diagnostic capabilities have decreased the number of iris leiomyoma diagnoses; many lesions previously thought to be a leiomyoma are now classified as spindle cell nevi or low-grade melanomas.[8]

Iridic nodules

Brushfield and Wolffilin spots are iris nodules that have been historically used as markers of trisomy 21; they are now considered clinically insignificant, and their exclusive association with light irises remains unexplained. Lisch nodules, characteristic of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), are dome-shaped melanocytic hamartomas on the iris surface that may appear clear, yellow, or brown. Lisch nodules are almost always present in patients with NF1 after 6 years of age and are one of the most common ocular pathognomonic markers for NF1.[9]

The presence of inflammatory iris nodules suggests systemic conditions like Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, or Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis. Infection with treponemes, mycobacteria, or rickettsiae has been linked to the formation of iris nodules.[10] Nodules may also be drug-induced or due to juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Vascular tumors of the iris

Iridic vascular tumors are most frequently a manifestation of systemic pathology, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Vascular tumors of the iris may infrequently be isolated arteriovenous malformations.[11]

Epidemiology

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the Iris

Despite being considered the most common intraocular malignancy, metastases to the iris only constitute approximately 2% of all iris tumors and 8% of all metastases to the eye.[2]

Iris melanoma

Iris melanomas account for 3% to 10% of uveal melanomas; the iris is the least common primary site for malignant melanoma.[1] However, melanoma is the most prevalent type of iris neoplasm, representing about 68% of all iris tumors. Notably, iris melanomas exhibit no preference for eye laterality or gender in populations younger than 65 years old; there is a higher incidence in men older than 65 years.[12]

Iris pigment epithelium adenocarcinoma

This neoplasm of pigment epithelium is exceedingly rare; approximately 1 case is reported annually in the United States. Published case reports are few.[6][13]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

Iris cysts are considered rare in the broader context of all ocular tumors. However, cystic lesions are a relatively frequent iris lesion. Shields et al reported that 21% of 3680 documented iris tumors were cystic lesions.[1]

Iris nevus

Iris nevi are rarely seen in childhood. However, these flat, pigmented lesions may be single or multifocal and are seen in almost 50% of adults.[14]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma accounted for less than 1% of iris tumors in a study of 3680 cases. Their rarity makes it challenging to establish predilections for age and gender; the suggested median age of diagnosis is 60 years.[15][16]

Iris leiomyoma

Generally favoring females and younger individuals, intraocular leiomyomata are exceptionally rare.[17]

Iridic nodules

Brushfield and Wolfillin spots are seen in approximately 10% of the population; the incidence increases from 21% to 63% when using infrared photography.[18] Lisch nodules are usually bilateral and multifocal; the occurrence of NF1 in the general population approximates 1 in 3500 live births.[9] Other nodule types are exceedingly uncommon and lack substantial supportive epidemiological data.[10]

Vascular tumors of the iris

Racemose hemangiomas are the dominant vascular tumor of the iris; this was reflected in a study demonstrating an incidence of 65% in patients with iridic vascular neoplasms. Cavernous hemangiomas, varix, microhemangiomatosis, arteriovenous malformation, and pediatric capillary hemangiomas collectively accounted for the remaining 35%. These tumors primarily affect middle-aged and older adults, are often unilateral, and display no gender preference.[11][19]

Histopathology

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the iris

The histopathology of metastases to the iris typically reflects the cytologic architecture of the primary neoplasm.[2]

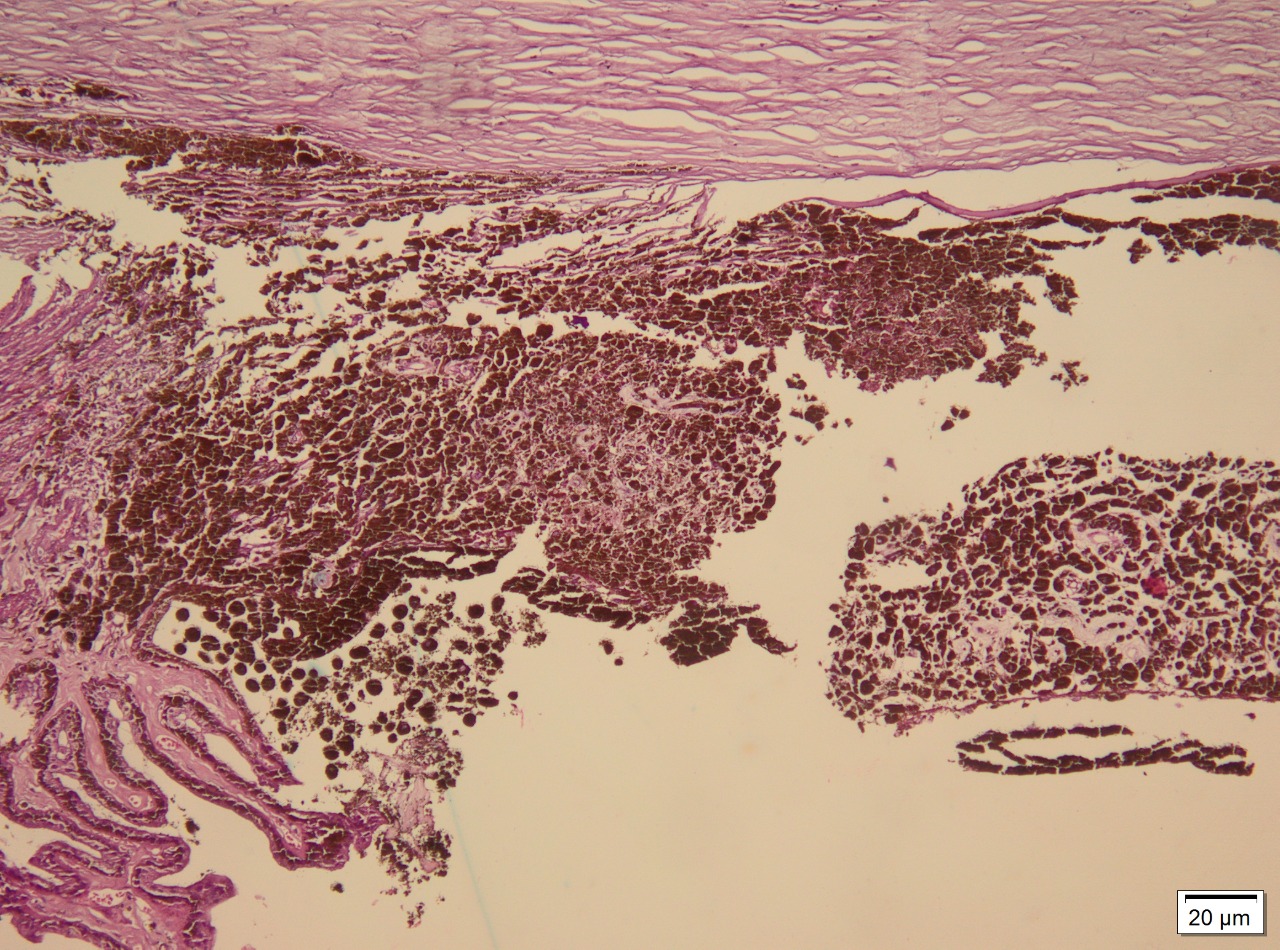

Iris melanoma

Melanoma cells are typically either spindle-shaped or epithelioid. Spindle cells exhibit elongated nuclei, mildly coarse chromatin, and eosinophilic nucleoli. Epithelioid cells possess abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, have distinct cell borders, and tend to be larger and pleomorphic. Some melanomas can comprise spindle and epithelioid cells (see Image. Iris Melanoma Markers).[5][20]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma and adenocarcinoma

Iris pigment epithelial adenomas are thought to be premalignant lesions; adenomas and adenocarcinomas share histologic characteristics. Iris pigment epithelium consists of heavily pigmented polygonal cells organized in sheets and cords. These tumors may be avascular with thin-walled vessels. Adenocarcinomas may exhibit tubuloacinar configurations. Infrequent mitotic figures and pleomorphic nuclei can be observed among cells with distinct borders and abundant cytoplasm.[21]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

Pigment epithelium cysts originating from the central or mid-zonal iris are composed of heavily pigmented columnar cells. Peripheral iris pigment epithelium cysts are partially lined with nonpigmented cells and may appear semitranslucent. Histologically, stromal cysts display stratified squamous epithelium or single layers of cuboidal cells often interspersed with goblet cells. This appearance suggests an ectodermal origin, potentially arising from surface ectoderm cells trapped in the stroma during embryogenesis.[22][23]

Iris nevus

Iris nevi cells are atypical and melanocytic yet benign by histological criteria. Predominantly spindle cells, these fusiform melanocytes typically possess small nuclei with either a small or absent nucleolus.[5]

Iris leiomyoma

Histologically, iris leiomyomas are characterized by spindle-shaped smooth muscle cells arranged in fascicles. These cells feature elongated, cigar-shaped nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm and are supported by a collagenous stroma. Immunohistochemical markers such as smooth muscle actin and desmin may offer diagnostic confirmation of leiomyomatous origin.[8]

Vascular tumors of the iris

These tumors often exhibit the cavernous vasculature commonly seen in vascular tumors. However, caution is advised; a study by Ferry revealed significant misdiagnosis of vascular tumors over melanomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas, as large vessels can obscure spindle cells and granular inflammation.[24]

History and Physical

Patients with iris tumors often have a discoloration or spot on the iris that is noticeable to them. Distorted or blurred vision is possible but uncommon, as is pain. A comprehensive medical history should be obtained, including inquiries into recent travel, trauma, and exposure to ocular foreign bodies.[1]

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the iris

Metastatic lesions of the iris are typically discovered after locating the primary neoplasm and usually appear amelanotic. Metastases can induce cellular shedding, resulting in hypopyon, clogging of the trabecular meshwork with subsequent increased intraocular pressure, or spontaneous hyphema.[2]

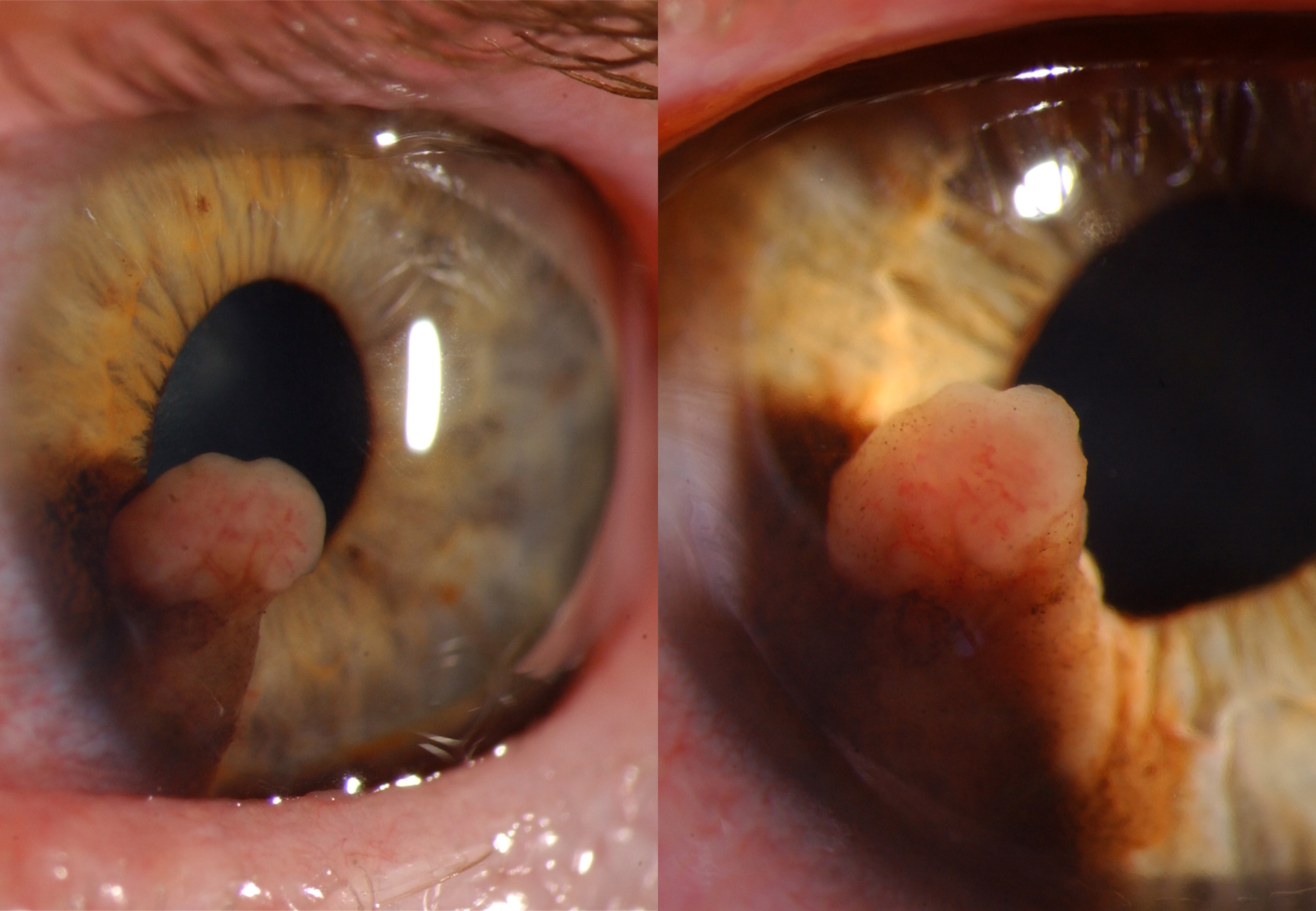

Iris melanoma

The most common sign of iris melanoma is a visible, elevated, dark, or amelanotic spot. Iris melanomas exhibit either a circumscribed (90%) or diffuse (10%) growth pattern.[25] Circumscribed melanomas usually have a flat or rounded anterior contour and are yellow or brown. Diffuse melanomas lack focal thickening and heterochromia, frequently involve the trabecular meshwork, and increase intraocular pressure.[12] Irregularly contoured lesions thicker than 0.5 to 1.0 mm are concerning for malignancy; increased vasculature, spontaneous hyphema formation, and pupillary peeking are also concerning features.[5] The mnemonic ABCDEF for Age, Blood, Clock hour, Diffuse configuration, Ectropion, and Feathery margins can aid assessment.[1][7]

Iris pigment epithelium adenocarcinoma

These tumors present as darkly pigmented, possibly multinodular masses. Patients are usually asymptomatic; vision loss is a possible symptom.[6]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

Pigment epithelium cysts are unilateral, darker structures that transilluminate. Stromal cysts are typically seen in the first decade of life and have a smooth, translucent anterior wall. Both cyst types can dislodge and become free-floating masses in the anterior chamber or vitreous; this is rare.[1]

Iris nevus

Nevi are typically smaller than melanomas, measuring less than 3mm in diameter and 1mm thick. Nevi occurring in conjunction with iridocorneal endothelial syndrome present as flat, pigmented lesions, often accompanied by stromal flattening, ectropion uvea, and pupil abnormalities.[7]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma

These neoplasms typically appear as a dark grey lesion at the iridic periphery, although they may be multinodular. Iris pigment epithelium adenomas can cause anterior displacement, stromal thinning, and erosion.[6][15]

Iris leiomyoma

Leiomyomata of the iris are typically solitary, slow-growing, well-demarcated, nodular lesions that may be nonpigmented or lightly pigmented.[8]

Iridic nodules

Inflammatory nodules are accompanied by cells in the anterior chamber or vitreous; aqueous flare and fibrin clot formation are frequent. Inflammatory nodules are lighter in color than Brushfield spots and Lisch nodules.[10] As iridic nodules are often a manifestation of systemic disease, a physical examination should be performed to assess the presence of skin lesions or splinter hemorrhages.[10][26] Yellow iridic nodules with hyphema and concomitant skin lesions suggest juvenile xanthogranulomas.[27] If sarcoidosis is suspected, chest imaging is recommended.

Vascular tumors of the iris

Vascular iridic tumors frequently present with spontaneous hyphema and subsequent blurred vision. Visualization of similar vascular anomalies elsewhere on the body may suggest an underlying systemic disorder; a thorough skin examination is recommended.[24]

Evaluation

Patients with iris tumors require a thorough examination with the slit lamp biomicroscope. Measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP) is recommended due to the glaucomatous potential of many iris tumors, and gonioscopy should be performed. Transillumination is a valuable tool when determining the nature of the lesion.[8] B-scan and ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) are also excellent diagnostic tools.[28][29]

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the iris

If the primary site of malignancy is unknown, a limbal puncture can be performed to obtain cells for histologic examination. A B-scan of the lesion will typically reveal an echodense mass.[2]

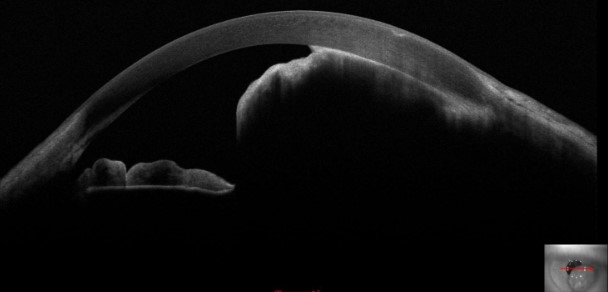

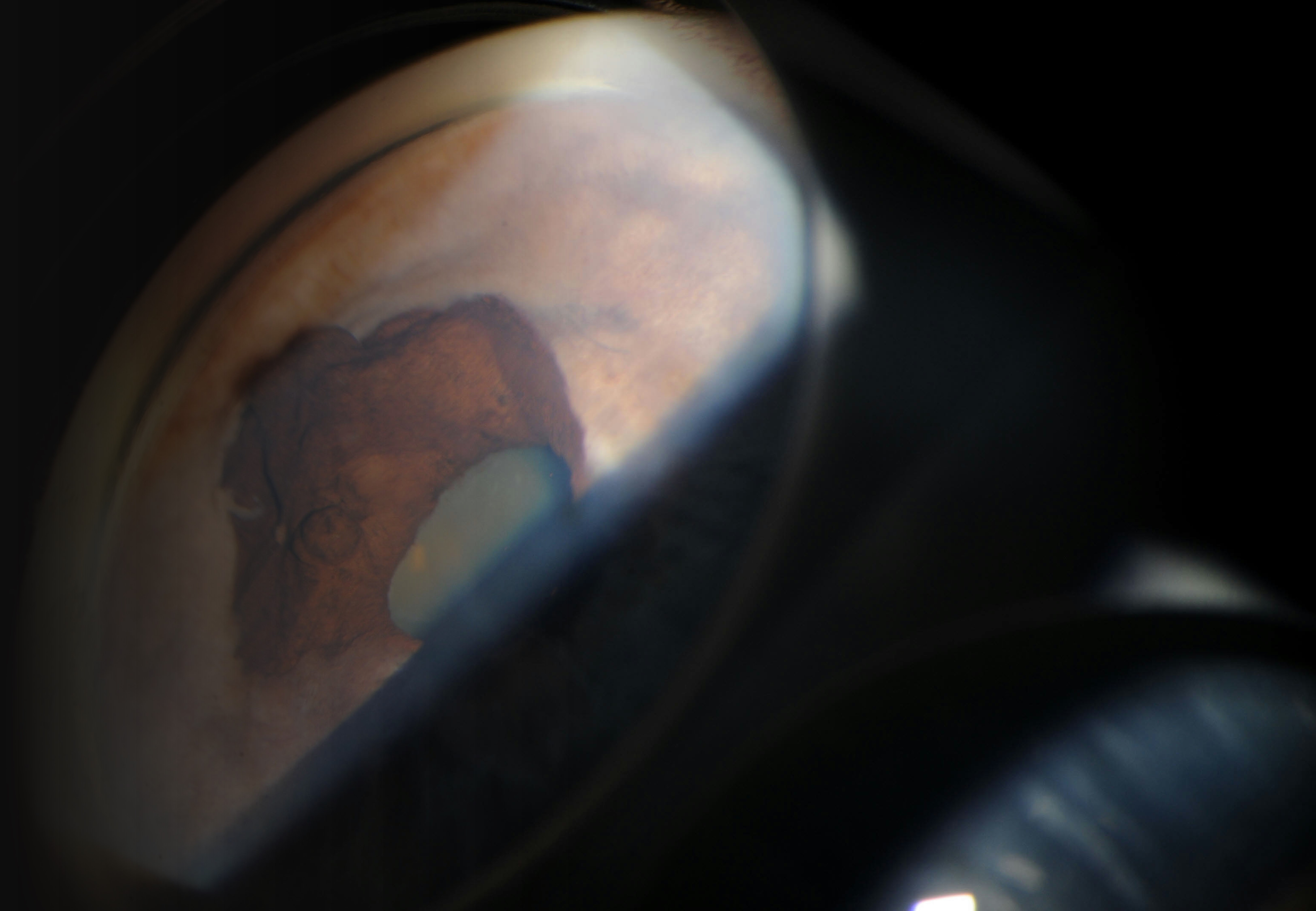

Iris melanoma

Transpupillary, transconjunctival, or transscleral illumination can be employed to assess if the shadow of the lesion extends to the pars plicata or pars plana regions and determine the posterior extent of the lesion.[25] Serial slit lamp photography can be used to follow lesional growth and contour changes. While smaller melanomas are typically well-visualized with anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), complete visualization of larger tumors frequently requires additional imaging techniques such as B-scan or UBM (see Image. Iris Melanoma Mass on Tomography). B-scan is typically the superior imaging technique for large lesions; sound waves better penetrate the ocular structures than the light waves of AS-OCT.[12] Fluorescein angiogram or optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) is particularly helpful when evaluating vascular melanomas, which often exhibit a late filling pattern. Incisional for fine-needle biopsy can be considered for suspicious lesions that cannot be confidently diagnosed by clinical features alone.[5][30]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma and adenocarcinoma

Examination with the slit lamp biomicroscope may reveal significant tissue erosion. However, as the literature about these tumors is sparse, ultrasound and biopsy should be performed.[6]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

B-scan and UBM aid in determining the extent of the lesion and distinguishing solid from cystic lesions. The shadowing of otherwise high-resolution images may limit the utility of AS-OCT. Fine needle aspiration may be necessary when noninvasive methods fail to confirm diagnosis.[22][28][29]

Iris nevus

Fluorescein angiogram or OCTA can be employed to evaluate iridic nevi; many studies indicate these studies offer little prognostic value. Most nevi exhibit a filling pattern of early hyperfluorescence and late leaking; melanomas have irregular vasculature and fill late. The utility of OCTA is somewhat limited; light waves penetrate highly pigmented lesions poorly.[7][31] B-Scan can be used to determine the size of the neoplasm, and FNA can be performed to determine the histopathology definitively.[5]

Iris leiomyoma

Immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy are essential confirmatory diagnostic tests for iridic leiomyomata, as these lesions are histopathologically complex and frequently mimic other neoplasms. Any potential angle involvement must be evaluated as secondary glaucoma is a common sequela.[8][32]

Iridic nodules

Anterior chamber paracentesis can be performed if the etiology of the nodule remains unclear after a comprehensive history is taken and a physical examination is performed. Paracentesis fluid can be sent for cytology, histologic evaluation, and culture.

Vascular tumors of the iris

Angiography, particularly fluorescein angiogram, is crucial when evaluating vascular tumors of the iris. Biopsy is rarely necessary but can be performed if angiography is nonconfirmatory.[24]

Treatment / Management

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the iris

Metastatic disease to the iris is non–life-threatening and rarely the initial presentation of a malignancy. Patients with metastatic disease to the iris are frequently already on systemic hormonal or chemotherapeutic regimens. The goal in treating iridic metastases is to preserve vision whenever possible. Consultation with the medical or surgical oncologist is warranted to assess the utility of systemic regimen modifications. Additionally, consultation with the ophthalmic oncologist for local radiation therapy with either EBRT or plaque radiotherapy may be indicated.[2]

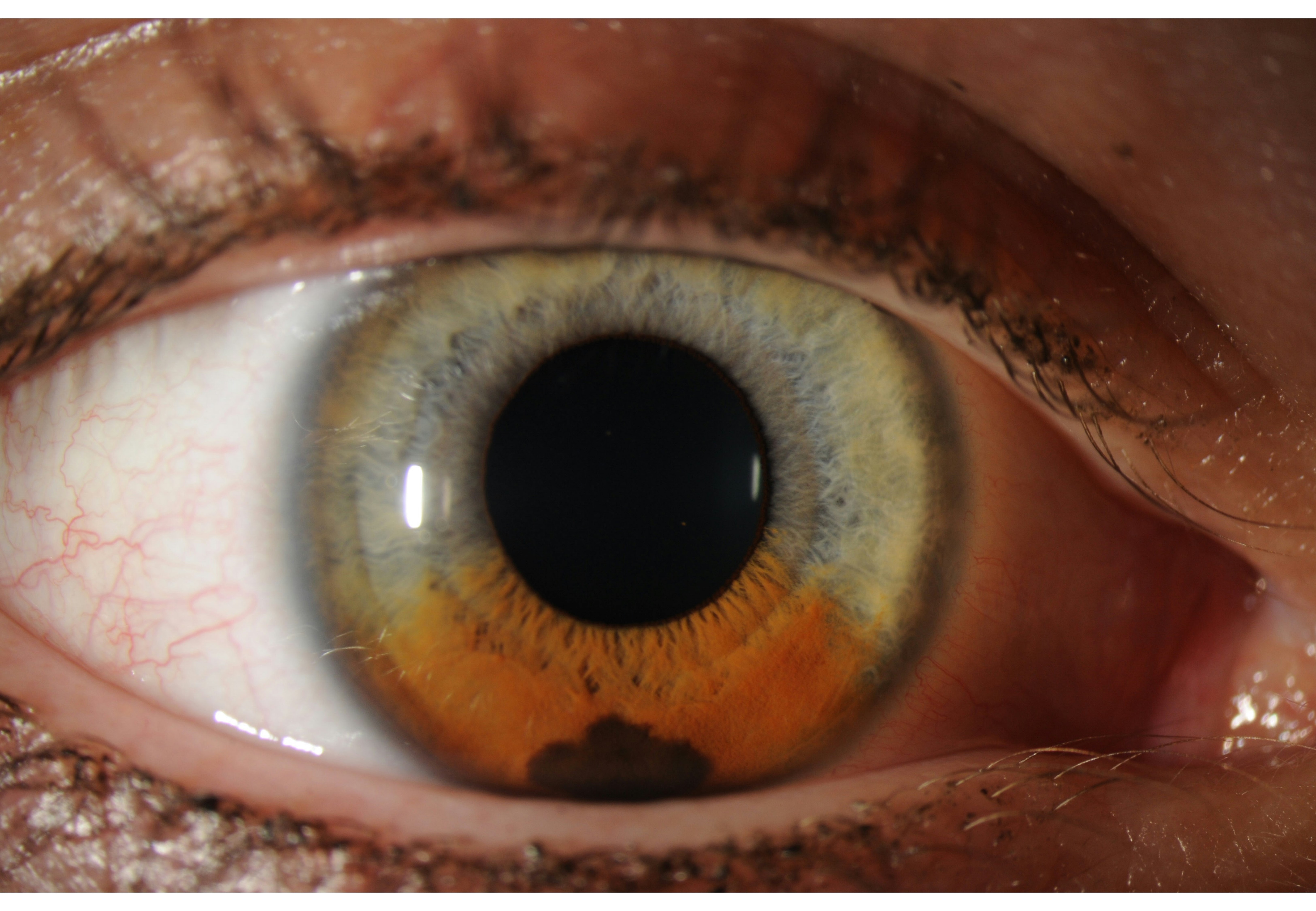

Iris melanoma

The treatment of iris melanoma is dictated by the clinical characteristics and behavior of the lesion. Small, well-circumscribed lesions may be closely followed with serial imaging and regular evaluation of intraocular pressure (see Image. Malignant Melanoma of Iris Typical Presentation.)[30] Proton beam therapy or plaque radiotherapy is indicated for extensive tumor seeding or nonresectable tumors; these treatments can result in vision loss. Surgical partial iridectomy may be a treatment option for symptomatic smaller melanomas. Iridotrabeculectomy may be indicated if the melanoma has invaded the trabecular meshwork. Iridocyclectomy is typically reserved for tumors exhibiting mild-to-moderate ciliary body invasion (see Image. Melanotic Malignant Melanoma.) Neoplasms that are large, diffuse, recurrent, or significantly impacting vision may require enucleation.[12]

Iris pigment epithelium adenocarcinoma

Treatment options include chemotherapy, radiation, surgical excision, or enucleation, depending on the size and invasiveness of the tumor.[6]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

Close observation is recommended if the cyst is stable, vision is not impacted, and the patient is asymptomatic. Intervention is warranted if the cyst increases in size or the patient becomes symptomatic. Noninvasive therapy is initially recommended via laser therapy or cyst aspiration with or without injection of sclerosing agents. Surgical excision can be considered if conservative efforts fail.[22](B3)

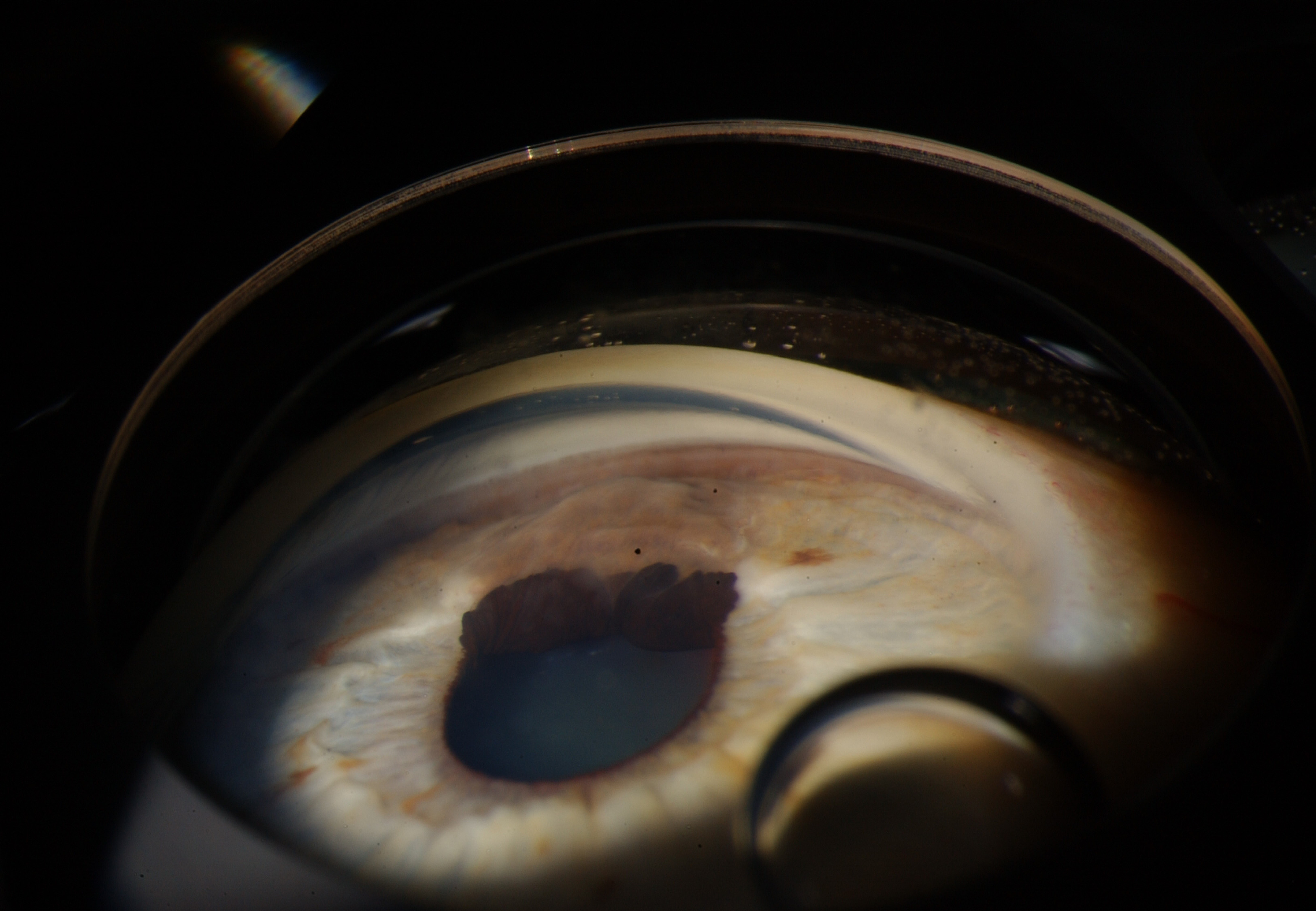

Iris nevus

Iris nevi are histologically benign, and observation is recommended. Small, unsuspicious nevi may be imaged every 12 to 24 months. Large, unsuspicious nevi may be imaged every 6 to 12 months. Nevi with suspicious characteristics should be closely followed, with comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation and imaging every 1 to 3 months. Once the stability of a nevus has been documented, patients can be evaluated annually (see Image. Iris Nevus).[5]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma

The management of an iris pigment epithelium adenoma is dictated by the presence of symptoms and the size and location of the tumor. Small, asymptomatic lesions may be managed conservatively with regular clinical evaluation. Adenomas that are large or symptomatic may be excised via iridocyclectomy or en bloc resection.[16](B3)

Iris leiomyoma

Iris leiomyomata are typically slow-growing, and observation with periodic monitoring may be a suitable approach for small, asymptomatic lesions. In a study by Tomar et al of 14 patients with bothersome leiomyomata, 1 patient underwent radiation therapy, and 13 underwent surgical excision via either iridectomy or iridocyclectomy. However, therapeutic enucleation has been employed for actively enlarging neoplasms or those invading the angle.[8][32](B3)

Iridic nodules

The treatment of an iridic nodule is dictated by the underlying etiology of the lesion. Infectious nodules should be treated with organism-specific systemic antimicrobial therapy; intraocular injection can be considered when systemic treatments fail.[10] Sarcoid iridic nodules typically respond to the immunosuppressive regimens employed to control systemic disease; local excision may be required to preserve or improve vision outcomes.[33] Drug-induced nodules, most commonly caused by propanolol, typically recede with discontinuation of the offending medication.[34] Patients with NF1 and Lisch nodules require regular observation due to the increased risk of malignant transformation.(B3)

Vascular tumors of the iris

Most vascular tumors of the iris are asymptomatic and require only regular observation. Serial imaging is recommended to evaluate and document any growth or architectural changes.[11](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for an iris lesion should include all iris tumors. Additional pathologic processes that may mimic a neoplasm include:

- Inflammatory granuloma

- Epithelial ingrowth

- Congenital iris heterochromia

- Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis

- Iris nevus syndrome

- Pigment dispersion

- Hemosiderosis

- Pigmentary glaucoma

- Ocular siderosis

Prognosis

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the iris

While untreated metastatic carcinomas carry an extremely poor ocular prognosis, overall prognosis and mortality are dictated by the tissue of origin. Cancers with uveal-type metastases, including iris metastases, have a cumulative overall survival rate of 32% at 3 years and 24% at 5 years. However, carcinoid tumors that metastasize to the iris have the most favorable 5-year survival rates at 92%, while kidney and pancreatic cancers that metastasize to the iris have 5-year survival rates of 0%.[2]

Iris melanoma

A retrospective study by Sabazade et al observed the 5-year mortality rate for iris melanoma to be 5%, rising to 8% at 10 to 20 years.[25] Histopathologic subtype and tumor size influence the prognosis of iris melanoma. Spindle cell melanomas generally have a better prognosis than epithelioid or mixed cell types; epithelioid melanoma is the more aggressive neoplasm. Local invasion of the choroid or ciliary body portends a worse prognosis. Diffuse melanomas have a higher rate of metastasis and poorer prognosis.[12] Demirci et al reported that in 25 patients with diffuse melanoma, the rate of metastasis was 13%.[35]

Iris pigment epithelium adenocarcinoma

No reports of iris pigment epithelium adenocarcinoma metastasizing exist, although the literature is sparse. Prognosis favors early detection; many cases of adenocarcinoma arise from the malignant transformation of an iris pigment epithelium adenoma. Larger, invasive, and symptomatic tumors carry a poorer prognosis.[6]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

The prognosis is dictated predominately by its invasiveness. However, stromal cysts carry a poorer prognosis than pigment epithelium cysts, and secondary cysts have a poorer prognosis than primary lesions, especially when the cyst occupies more than one-half of the anterior chamber.[22]

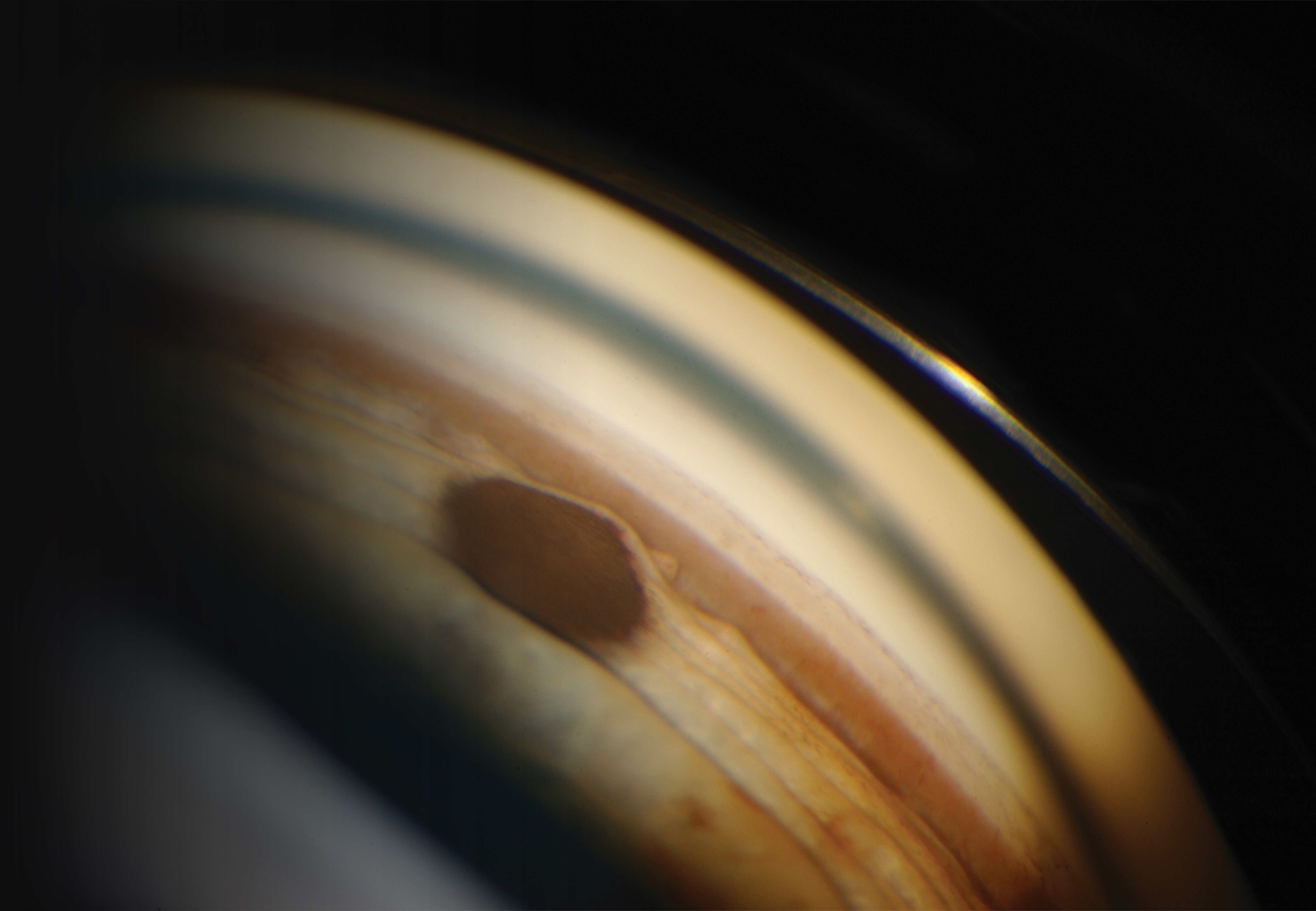

Iris nevus

The prognosis for iris nevi is generally favorable. Most iris nevi remain stable and do not exhibit malignant transformation (see Image. Iris Nevus Gonioscopy).[36]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma

The prognosis of this tumor type is generally favorable, provided that malignant transformation does not occur. Iris adenomas require long-term monitoring for recurrence or transformation.[6]

Iris leiomyoma

The prognosis of iris leiomyomata is generally excellent. Long-term follow-up is important to monitor for any complications or disease recurrence, although recurrence is rare.[8]

Iridic nodules

Early diagnosis and treatment of underlying disease processes are proportionally related to prognosis in most iris nodules. In many cases, iris nodules indicate a later stage of disease; prompt diagnosis and referral for disease-specific treatment are imperative.[34]

Vascular tumors of the iris

The prognosis in the majority of patients presenting with vascular tumors is quite favorable. Prognoses tend to be poorer or more variable if the iris tumor is a manifestation of systemic disease.[37]

Complications

Malignant Lesions

Metastases to the iris

Due to the discohesive nature of metastases to the iris, secondary open-angle glaucoma may arise. Clinicians should proactively lower intraocular pressure, but filtering surgeries are not recommended.[2]

Iris melanoma

Secondary glaucoma is a common complication of iris melanoma. Filtering surgery for melanoma-associated glaucoma should be avoided due to tumor dissemination risk.[12]

Iris pigment epithelium adenoma and adenocarcinoma

These tumors can sometimes cause anterior displacement, stromal thinning, and erosion.[6]

Benign Lesions

Iris cysts

Epithelial and stromal cysts may dislodge and become free-floating in the anterior chamber or vitreous, but this is uncommon.[1]

Iris nevus

Many of the complications associated with iris nevi are due to either malignant transformation or deterioration of vision. These complications require a shift from clinical observation to intervention.[7]

Iris leiomyoma

Iris leiomyomata are typically not bothersome and amenable to long-term observation. However, in rare circumstances, the leiomyoma can exhibit uncharacteristic rapid growth and invade adjacent structures such as the angles. This behavior may warrant enucleation.[32]

Iridic nodules

Shields et al found that 34% of patients undergoing fine-needle aspirational biopsy experienced an immediate partial hyphema, although an adequate tissue sample was collected in 99% of patients. While the complications of iris nodules typically reflect their systemic etiology, clinicians should be aware of the possible complications from invasive diagnostic tools; this is true for all iris tumors.[38]

Vascular tumors of the iris

The most common complication of vascular tumors is spontaneous hyphema; these typically resolve with topical treatments. Additionally, these tumors may complicate other procedures, such as phacoemulsification. A study from 2022 reported that 1 patient undergoing phacoemulsification with a concomitant vascular iridic tumor experienced mild intraoperative bleeding easily controlled by increasing pressure in the anterior chamber with cohesive viscoelastic. It has been recommended to perform prophylactic photocoagulation with an argon laser to avoid intraoperative bleeding, although this practice is not universal.[11]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with iris tumors should be educated regarding the risks of their particular neoplasm, particularly related to any potential underlying risks of malignant transformation. Close adherence to observation protocols is imperative. Additionally, as many iris tumors carry a significant risk of secondary glaucomatous change, patients must be educated to seek medical attention for any changes in vision, the acute onset of eye pain, or visible changes in the neoplasm.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Most patients with an iris tumor notice the abnormality themselves or those around them note it. Patients will frequently present to a primary care practitioner or general optometrist; if the tumor is causing acute pain or vision changes, the patient may present to an urgent care clinic or emergency department. While many iridic lesions are benign, some are not, and a comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation is necessary to determine the nature of the neoplasm. Prompt recognition of iris tumors with proper specialty referral is imperative for accurate diagnosis.

The specific etiology of the iris tumor will determine the treatment plan, which may include referrals to subspecialty medical practitioners or ocular, medical, or surgical oncologists. Regardless of the etiology, many patients with iris tumors will require long-term monitoring of the lesion by eye care professionals.

Thorough written and photographic documentation of the iris lesion(s) is critical to monitor changes in tumor size, growth patterns, and patient symptomatology. Continuity of care and patient adherence to long-term follow-up must be emphasized to improve vision outcomes, morbidity, and, in cases of malignant iris neoplasms, mortality.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Shields CL, Shields PW, Manalac J, Jumroendararasame C, Shields JA. Review of cystic and solid tumors of the iris. Oman journal of ophthalmology. 2013 Sep:6(3):159-64. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.122269. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24379549]

Shields CL, Kalafatis NE, Gad M, Sen M, Laiton A, Silva AMV, Agrawal K, Lally SE, Shields JA. Metastatic tumours to the eye. Review of metastasis to the iris, ciliary body, choroid, retina, optic disc, vitreous, and/or lens capsule. Eye (London, England). 2023 Apr:37(5):809-814. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02015-4. Epub 2022 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 35306540]

Kalirai H, Dodson A, Faqir S, Damato BE, Coupland SE. Lack of BAP1 protein expression in uveal melanoma is associated with increased metastatic risk and has utility in routine prognostic testing. British journal of cancer. 2014 Sep 23:111(7):1373-80. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.417. Epub 2014 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 25058347]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRONES B, ZIMMERMAN LE. The prognosis of primary tumors of the iris treated by iridectomy. A.M.A. archives of ophthalmology. 1958 Aug:60(2):193-205 [PubMed PMID: 13558786]

Krantz BA, Dave N, Komatsubara KM, Marr BP, Carvajal RD. Uveal melanoma: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of primary disease. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2017:11():279-289. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S89591. Epub 2017 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 28203054]

Dryja TP, Zakov ZN, Albert DM. Adenocarcinoma arising from the epithelium of the iris and ciliary body. International ophthalmology clinics. 1980 Summer:20(2):177-90 [PubMed PMID: 6995386]

Shields CL, Kaliki S, Hutchinson A, Nickerson S, Patel J, Kancherla S, Peshtani A, Nakhoda S, Kocher K, Kolbus E, Jacobs E, Garoon R, Walker B, Rogers B, Shields JA. Iris nevus growth into melanoma: analysis of 1611 consecutive eyes: the ABCDEF guide. Ophthalmology. 2013 Apr:120(4):766-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.042. Epub 2013 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 23290981]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYeaney GA, Platt S, Singh AD. Primary iris leiomyoma. Survey of ophthalmology. 2017 May-Jun:62(3):366-370. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.11.007. Epub 2016 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 27890619]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLubs ML, Bauer MS, Formas ME, Djokic B. Lisch nodules in neurofibromatosis type 1. The New England journal of medicine. 1991 May 2:324(18):1264-6 [PubMed PMID: 1901624]

Myers TD, Smith JR, Lauer AK, Rosenbaum JT. Iris nodules associated with infectious uveitis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2002 Sep:86(9):969-74 [PubMed PMID: 12185117]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCalleja-García C, Suárez-Baraza J, Mencía-Gutiérrez E. Iris Vascular Malformation with 360-Degree Iridocorneal Angle Affectation. Case reports in ophthalmological medicine. 2020:2020():5913636. doi: 10.1155/2020/5913636. Epub 2020 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 32566340]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaliki S, Shields CL. Uveal melanoma: relatively rare but deadly cancer. Eye (London, England). 2017 Feb:31(2):241-257. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.275. Epub 2016 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 27911450]

VRABEC F, SOUKUP F. MALIGNANT EPITHELIOMA OF THE PIGMENTED EPITHELIUM OF THE HUMAN IRIS. American journal of ophthalmology. 1963 Sep:56():403-9 [PubMed PMID: 14064886]

Laino AM, Berry EG, Jagirdar K, Lee KJ, Duffy DL, Soyer HP, Sturm RA. Iris pigmented lesions as a marker of cutaneous melanoma risk: an Australian case-control study. The British journal of dermatology. 2018 May:178(5):1119-1127. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16323. Epub 2018 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 29315480]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShields CL, Kancherla S, Patel J, Vijayvargiya P, Suriano MM, Kolbus E, Badami A, Sharma P, Jacobs E, Voluck M, Zhang Z, Kansal R, Shields PW, Bianciotto CG, Shields JA. Clinical survey of 3680 iris tumors based on patient age at presentation. Ophthalmology. 2012 Feb:119(2):407-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.059. Epub 2011 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 22035581]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShields JA, Shields CL, Mercado G, Gündüz K, Eagle RC Jr. Adenoma of the iris pigment epithelium: a report of 20 cases: the 1998 Pan-American Lecture. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1999 Jun:117(6):736-41 [PubMed PMID: 10369583]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShields JA, Shields CL. Observations on intraocular leiomyomas. Transactions - Pennsylvania Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. 1990:42():945-50 [PubMed PMID: 2084991]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePostolache L, Parsa CF. Brushfield spots and Wölfflin nodules unveiled in dark irides using near-infrared light. Scientific reports. 2018 Dec 21:8(1):18040. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36348-6. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30575783]

Eguilior Álvarez R, Marticorena-Álvarez P. Multimodal Imaging in Iris Vascular Tumors: A Case Series. Cureus. 2022 Nov:14(11):e31741. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31741. Epub 2022 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 36569711]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcLean IW, Foster WD, Zimmerman LE, Gamel JW. Modifications of Callender's classification of uveal melanoma at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. American journal of ophthalmology. 1983 Oct:96(4):502-9 [PubMed PMID: 6624832]

Shields JA, Augsburger JJ, Sanborn GE, Klein RM. Adenoma of the iris-pigment epithelium. Ophthalmology. 1983 Jun:90(6):735-9 [PubMed PMID: 6888863]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGeorgalas I, Petrou P, Papaconstantinou D, Brouzas D, Koutsandrea C, Kanakis M. Iris cysts: A comprehensive review on diagnosis and treatment. Survey of ophthalmology. 2018 May-Jun:63(3):347-364. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.08.009. Epub 2017 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 28882598]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaul TO, Spencer WH, Webster R. Congenital intrastromal epithelial cyst of the iris. Annals of ophthalmology. 1994 May-Jun:26(3):94-6 [PubMed PMID: 7944162]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShields JA, Bianciotto C, Kligman BE, Shields CL. Vascular tumors of the iris in 45 patients: the 2009 Helen Keller Lecture. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2010 Sep:128(9):1107-13. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20837792]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSabazade S, Herrspiegel C, Gill V, Stålhammar G. No differences in the long-term prognosis of iris and choroidal melanomas when adjusting for tumor thickness and diameter. BMC cancer. 2021 Nov 24:21(1):1270. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-09002-0. Epub 2021 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 34819035]

Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. NF1 gene and neurofibromatosis 1. American journal of epidemiology. 2000 Jan 1:151(1):33-40 [PubMed PMID: 10625171]

Zamir E, Wang RC, Krishnakumar S, Aiello Leverant A, Dugel PU, Rao NA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma masquerading as pediatric chronic uveitis: a clinicopathologic study. Survey of ophthalmology. 2001 Sep-Oct:46(2):164-71 [PubMed PMID: 11578649]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceConway RM, Chew T, Golchet P, Desai K, Lin S, O'Brien J. Ultrasound biomicroscopy: role in diagnosis and management in 130 consecutive patients evaluated for anterior segment tumours. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Aug:89(8):950-5 [PubMed PMID: 16024841]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePilling RF, Khan A, Ball JL. The utility of anterior segment optical coherence tomography in monitoring intraocular epithelial cysts in children: a mini case series. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Sep:94(9):1265. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.151571. Epub 2010 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 20511634]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKrohn J, Sundal KV, Frøystein T. Topography and clinical features of iris melanoma. BMC ophthalmology. 2022 Jan 3:22(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12886-021-02236-3. Epub 2022 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 34980044]

Skalet AH, Li Y, Lu CD, Jia Y, Lee B, Husvogt L, Maier A, Fujimoto JG, Thomas CR Jr, Huang D. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Characteristics of Iris Melanocytic Tumors. Ophthalmology. 2017 Feb:124(2):197-204. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.10.003. Epub 2016 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 27856029]

Tomar AS, Finger PT, Iacob CE. Intraocular leiomyoma: Current concepts. Survey of ophthalmology. 2020 Jul-Aug:65(4):421-437. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.12.008. Epub 2020 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 31923479]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOcampo VV Jr, Foster CS, Baltatzis S. Surgical excision of iris nodules in the management of sarcoid uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2001 Jul:108(7):1296-9 [PubMed PMID: 11425690]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYeomans SM, Knox DL, Green WR, Murgatroyd GW. Ocular inflammatory pseudotumor associated with propranolol therapy. Ophthalmology. 1983 Dec:90(12):1422-5 [PubMed PMID: 6687156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDemirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC Jr, Honavar SG. Diffuse iris melanoma: a report of 25 cases. Ophthalmology. 2002 Aug:109(8):1553-60 [PubMed PMID: 12153810]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFoti PV, Travali M, Farina R, Palmucci S, Spatola C, Raffaele L, Salamone V, Caltabiano R, Broggi G, Puzzo L, Russo A, Reibaldi M, Longo A, Vigneri P, Avitabile T, Ettorre GC, Basile A. Diagnostic methods and therapeutic options of uveal melanoma with emphasis on MR imaging-Part I: MR imaging with pathologic correlation and technical considerations. Insights into imaging. 2021 Jun 3:12(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s13244-021-01000-x. Epub 2021 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 34080069]

Thomas-Sohl KA, Vaslow DF, Maria BL. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review. Pediatric neurology. 2004 May:30(5):303-10 [PubMed PMID: 15165630]

Shields CL, Manquez ME, Ehya H, Mashayekhi A, Danzig CJ, Shields JA. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of iris tumors in 100 consecutive cases: technique and complications. Ophthalmology. 2006 Nov:113(11):2080-6 [PubMed PMID: 17074566]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence