Introduction

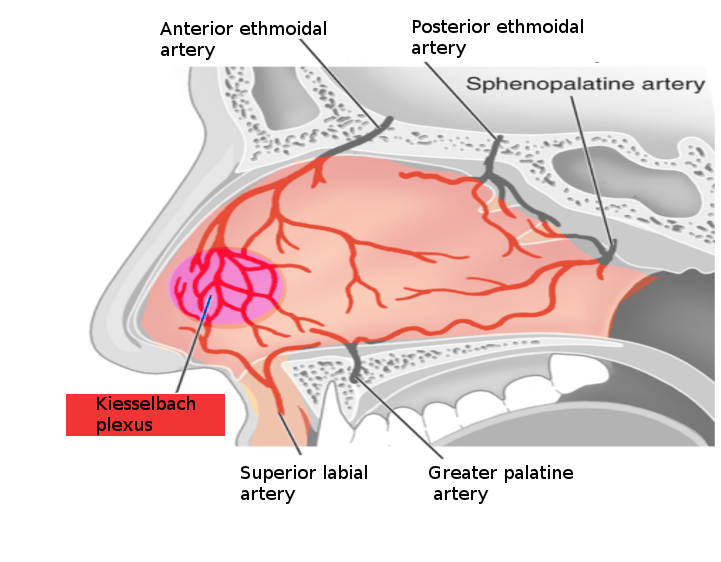

Epistaxis (nosebleed) is one of the most common ear, nose, and throat emergencies in the emergency department or the primary care clinic. There are 2 types of nosebleeds: anterior (more common) and posterior (less common but more likely to require medical attention). The source of 90% of anterior nosebleeds is within Kiesselbach plexus (also known as Little's area) on the anterior nasal septum. There are 5 named vessels whose terminal branches supply the nasal cavity.

- Anterior ethmoidal artery

- Posterior ethmoidal artery

- Sphenopalatine artery

- Greater palatine artery

- Superior labial artery

These 5 vessels' watershed areas are in the anterior nasal septum, comprising Kiesselbach plexus. This lies at the entrance to the nasal cavity and is subject to extremes of heat, cold, and high and low moisture; it is easily traumatized. The mucosa over the septum in this area is fragile, making this the site of most epistaxis. More rarely, posterior or superior nasal cavity vessels bleed, leading to the so-called "posterior" epistaxis. This is more common in patients on anticoagulants, patients who are hypertensive, and patients with underlying blood dyscrasia or vascular abnormalities. Management depends on the severity of the bleeding and the patient's concurrent medical problems.[1][2][3] See Image. Nosebleed Vessels.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are multiple causes of epistaxis, which can be divided into local, systemic, environmental, and medication-induced.

Local Causes

Local causes of epistaxis include:

- Digital manipulation

- Deviated septum

- Trauma

- Chronic nasal cannula use

Systemic Causes

Local causes of epistaxis include:

- Alcoholism

- Hypertension

- Vascular malformations

- Coagulopathies (von Willebrand disease, hemophilia)

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors in epistaxis include:

- Allergies

- Environmental dryness (more common in winter months)

Medications

Medications that can cause epistaxis include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs; ibuprofen, naproxen, aspirin)

- Anticoagulants (warfarin)

- Platelet aggregation inhibitors (clopidogrel)

- Topical nasal steroid sprays

- Supplements or alternative medications (vitamin E, ginkgo, ginseng)

- Illicit drugs (cocaine)

While epistaxis is a widespread spontaneous problem, rarer etiologies such as neoplasms or vascular malformations must always be in the differential diagnosis, particularly if additional symptoms such as unilateral nasal obstruction, pain, or other cranial nerve deficits are noted.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Nosebleeds are rarely fatal, accounting for only 4 of the 2.4 million deaths in the United States. About 60% of people have experienced a nosebleed, and only 10% are severe enough to warrant treatment or medical intervention. They occur most commonly in children aged 2 to 10 years old and older people between 50 and 80.

Pathophysiology

The rupture of a blood vessel within the nasal mucosa causes nosebleeds. Rupture can be spontaneous, initiated by trauma, use of certain medications, and secondary to other comorbidities or malignancies. An increase in the patient's blood pressure can increase the episode's length. Anticoagulant medications, as well as clotting disorders, can also increase the bleeding time.

Most nosebleeds occur in the anterior part of the nose (Kiesselbach plexus), and an etiologic vessel can usually be found on careful nasal examination. Bleeding from the posterior or superior nasal cavity is often termed a posterior nosebleed. This is usually presumed due to bleeding from the Woodruff plexus, the rear, and fine terminal branches of the sphenopalatine and posterior ethmoidal arteries. These are often difficult to control and are associated with bleeding from both nostrils or into the nasopharynx, where it is swallowed or coughed up, presenting as hemoptysis. This can generate a greater blood flow into the posterior pharynx, and there is a higher risk for airway compromise or aspiration due to increased difficulty controlling the bleeding.

History and Physical

The history should include duration, severity, frequency, laterality of the bleeding, inciting event, and interventions provided before seeking care. Inquire about anticoagulants, aspirin, NSAIDs, and topical nasal steroid use. Obtain a relevant family history, particularly relating to coagulopathy and vascular/collagen disease, as well as any history of drug and alcohol use.

Prepare proper equipment and proper personal protective equipment before beginning the physical examination. Equipment may include a nasal speculum, bayonet forceps, headlamp, suction catheter, packing, silver nitrate swabs, cotton pledgets, topical vasoconstrictor, and anesthetic. Have the patient seated in an exam chair in a room with suction available. Carefully insert the speculum and slowly open the blades to visualize the bleeding site. A headlight is essential for hands-free illumination, and the clot may need to be suctioned from the nasal cavity to identify the bleeding source. A posterior nosebleed is not easy to visualize and may be suggested by active bleeding into the posterior pharynx without a visualized vessel on nasal examination. Nasal endoscopy dramatically increases the success rate of identifying the bleeding source.

Evaluation

Differentiating an anterior or posterior nosebleed is critical in management. Diagnosis of anterior bleeding can be made by direct visualization using a nasal speculum and light source. A topical spray with anesthetic and epinephrine may be helpful for vasoconstriction to help control bleeding and to aid in the visualization of the source. Usually, posterior bleeding is diagnosed after measures to control anterior bleeding have failed. Clinical features of posterior bleeding can include active bleeding into the posterior pharynx without an identified anterior source; high-flow posterior bleeds may cause blood to emanate from both nares. Labs may be obtained if necessary, including a complete blood cell count, type and cross match, and coagulation studies, though they should not delay treatment of an active bleed. Imaging such as x-rays or computed tomography have no role in the urgent or emergent management of active epistaxis.

Treatment / Management

Start with a primary survey and address the airway, ensuring it is patent. Next, assess for hemodynamic compromise. Obtain large-bore intravenous access in patients with severe bleeding and obtain labs. Reverse blood clotting as necessary if there is a concern with medication use.[7][8][9] All patients with moderate to severe nose bleeding should have 2 large-bore intravenous lines and an infusion of crystalloid. Monitoring oxygen and hemodynamic stability is vital.(A1)

Treatment for anterior bleeding can be started with direct pressure for at least 10 minutes. Have the patient apply constant direct pressure by pinching the nose over the cartilaginous tip (instead of over the bony areas) for a few minutes to control the bleeding. Vasoconstrictors such as oxymetazoline or thrombogenic foams or gels can be employed if that is ineffective. Remove all clots with suction before any attempt at treatment is made. The reasons are 2-fold:

- Clot prevents any medication from reaching the vessel.

- If packing becomes necessary, the clot can be pushed into the nasopharynx and aspirated.

If topical treatments are unsuccessful, proceed with nasal examination to identify and cauterize the vessel with silver nitrate. If this is unsuccessful, anterior nasal packing is necessary. This can be performed with absorbable packing material such as surgical or fibrillar or with devices such as anterior epistaxis balloons or nasal tampons. If silver nitrate is used to cauterize a septal blood vessel, only use it on 1 side of the septum to prevent septal perforation. Thermal coagulation is painful and should rarely be attempted in an emergent setting.

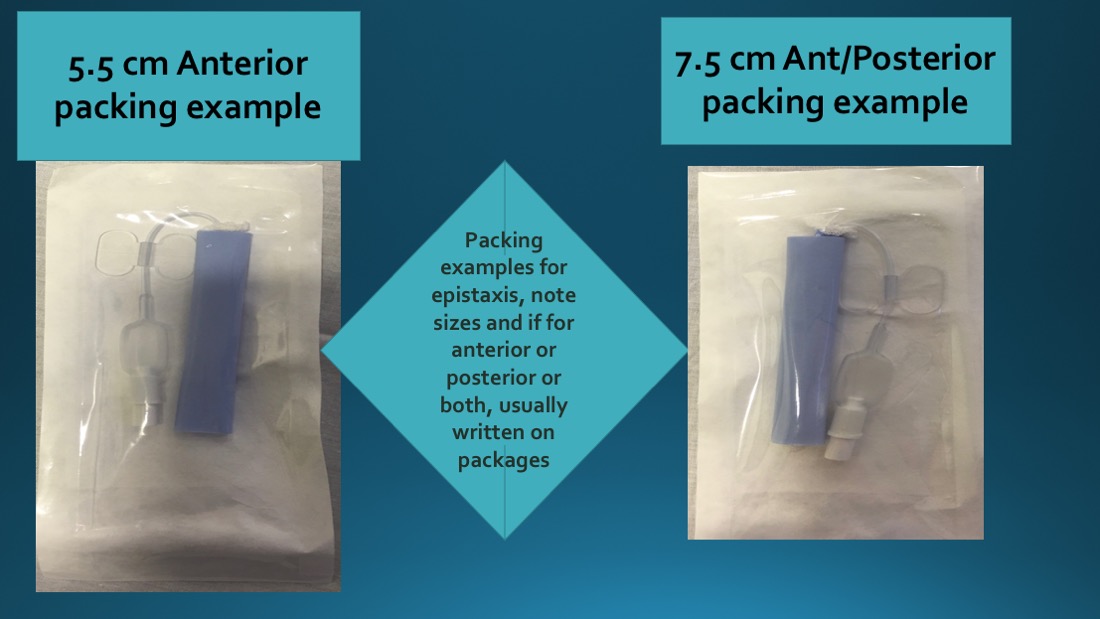

Traditional petrolatum gauze can be used if one does not have access to balloons or tampons. If none of this is successful, the bleeding may be from the posterior or superior nasal cavity. Symptoms can include active bleeding from both nostrils or active bleeding present in the posterior pharynx. Longer (7.5 cm) nasal tampons provide more posterior pressure and can be employed in this situation. Formal posterior nasal packing should only be performed by experienced personnel as it requires admission, telemetry monitoring, and sometimes intubation; this is associated with higher rates of complications like pressure necrosis, infection, or hypoxia. A nasal-cardiac reflex may be triggered (ie, sudden bradycardia after nasal packing); if this occurs, remove the pack immediately). Foley catheters can be used by experienced personnel to tamponade a posterior bleed. If a rear pack is placed, a formal petrolatum gauze anterior pack must also be set to create a closed, tamponaded space in the nasopharynx. If these measures are unsuccessful, the patient should be intubated for airway protection, and interventional radiology should be consulted emergently for embolization. If this service is unavailable, an otolaryngologist can perform operative ligation of the sphenopalatine and ethmoid arteries in the operating room.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for epistaxis include the following:

- Nasal tumor

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Hemophilia

- Von Willebrand disease

- Rhinitis

- Foreign body in the nose

- Drug toxicity (warfarin, NSAIDs)

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Once the bleeding is controlled, arranging a timely follow-up (within 1 week) with their primary care clinician or an otolaryngologist is essential. If any packing has been placed, this must remain undisturbed for 3 to 5 days before removal. Patients should begin an antistaphylococcal antibiotic to prevent toxic shock syndrome. Underlying causes must be addressed before discharge (eg, tight blood pressure control with goal systolic blood pressure less than 120 mm Hg), and patients should use topical nasal saline in both nares to keep the packs moist and facilitate removal.

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients with anterior nosebleeds can be discharged if the bleeding is controlled, hemodynamic stability is observed for at least 1 hour in the emergency department, and all predisposing factors are medically optimized. Follow-up with an otolaryngologist or their primary clinician should occur in 1 week, and they should begin nasal saline 3 times daily. If nonbiodegradable packing is used, patients should return to the emergency department or ear, nose, and throat clinician for packing removal in 3 to 5 days.

If a patient, including pediatric patients, requires posterior packing, admission is required to monitor for complications, particularly cardiac arrhythmias. All anticoagulants should ideally be discontinued but must be reversed or withheld to achieve the lowest dose acceptable if discontinuation is impossible. Applying topical saline sprays or ointments to the nasal mucosa to ensure moisturization of the nasal mucosa can help prevent recurrent epistaxis. Patients should also be advised to avoid hot foods, strenuous activity, blowing the nose, or digital manipulation of the nose on discharge.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team best performs the care of nose bleeding. Most patients initially present to the emergency room; the triage nurse should fully know the importance of admitting patients with significant bleeding. While most anterior nosebleeds can be arrested with digital pressure, a follow-up appointment is recommended in patients with repeat episodes. Even though nurses may not perform invasive procedures to stop the bleeding, they can effectively instruct patients to properly compress the nose with their fingers, which can arrest the bleeding in most cases.

Nasal packing is another option, but the packing must be in place for 3 to 5 days, and repeated insertions and removals of various packs only exacerbate the bleeding (see Image. Epistaxis Management Supplies). Drug-induced nosebleeds may require a reversal of the international normalized ratio and admission. The pharmacist should ensure that the patient does not restart the NSAID or other anticoagulant while the bleeding is active. A hematologist consult is recommended to deal with patients with coagulopathy. In rare cases, embolization or cauterization may be required to stop a nosebleed. An ear, nose, and throat consultation is necessary if the bleeding is posterior and severe.

In some cases, the invasive radiologist may be required to perform embolization to stop the bleeding. Nurses should monitor the oxygen and hemodynamic status of all patients with moderate to severe nose bleeds. These patients should have intravenous access to the transfusion of crystalloids. The team members should communicate to ensure that the patient receives an acceptable standard of care treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Fishman J, Fisher E, Hussain M. Epistaxis audit revisited. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2018 Dec:132(12):1045. doi: 10.1017/S0022215118002311. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30674370]

Send T, Bertlich M, Eichhorn KW, Ganschow R, Schafigh D, Horlbeck F, Bootz F, Jakob M. Etiology, Management, and Outcome of Pediatric Epistaxis. Pediatric emergency care. 2021 Sep 1:37(9):466-470. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001698. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30624421]

Kitamura T, Takenaka Y, Takeda K, Oya R, Ashida N, Shimizu K, Takemura K, Yamamoto Y, Uno A. Sphenopalatine artery surgery for refractory idiopathic epistaxis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Aug:129(8):1731-1736. doi: 10.1002/lary.27767. Epub 2019 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 30613985]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceINTEGRATE (UK National ENT research trainee network) on its behalf:, Mehta N, Stevens K, Smith ME, Williams RJ, Ellis M, Hardman JC, Hopkins C. National prospective observational study of inpatient management of adults with epistaxis - a National Trainee Research Collaborative delivered investigation. Rhinology. 2019 Jun 1:57(3):180-189. doi: 10.4193/Rhin18.239. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30610832]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceClark M, Berry P, Martin S, Harris N, Sprecher D, Olitsky S, Hoag JB. Nosebleeds in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Development of a patient-completed daily eDiary. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2018 Dec:3(6):439-445. doi: 10.1002/lio2.211. Epub 2018 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 30599027]

Ramasamy V, Nadarajah S. The hazards of impacted alkaline battery in the nose. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2018 Sep-Oct:7(5):1083-1085. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_47_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30598962]

Joseph J, Martinez-Devesa P, Bellorini J, Burton MJ. Tranexamic acid for patients with nasal haemorrhage (epistaxis). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Dec 31:12(12):CD004328. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004328.pub3. Epub 2018 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 30596479]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWong AS, Anat DS. Epistaxis: A guide to assessment and management. The Journal of family practice. 2018 Dec:67(12):E13-E20 [PubMed PMID: 30566119]

Santander MJ, Rosenbaum A, Winter M. Topical tranexamic acid for spontaneous epistaxis. Medwave. 2018 Dec 10:18(8):e7372. doi: 10.5867/medwave.2018.08.7371. Epub 2018 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 30550535]