Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inferior Gluteal Nerve

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inferior Gluteal Nerve

Introduction

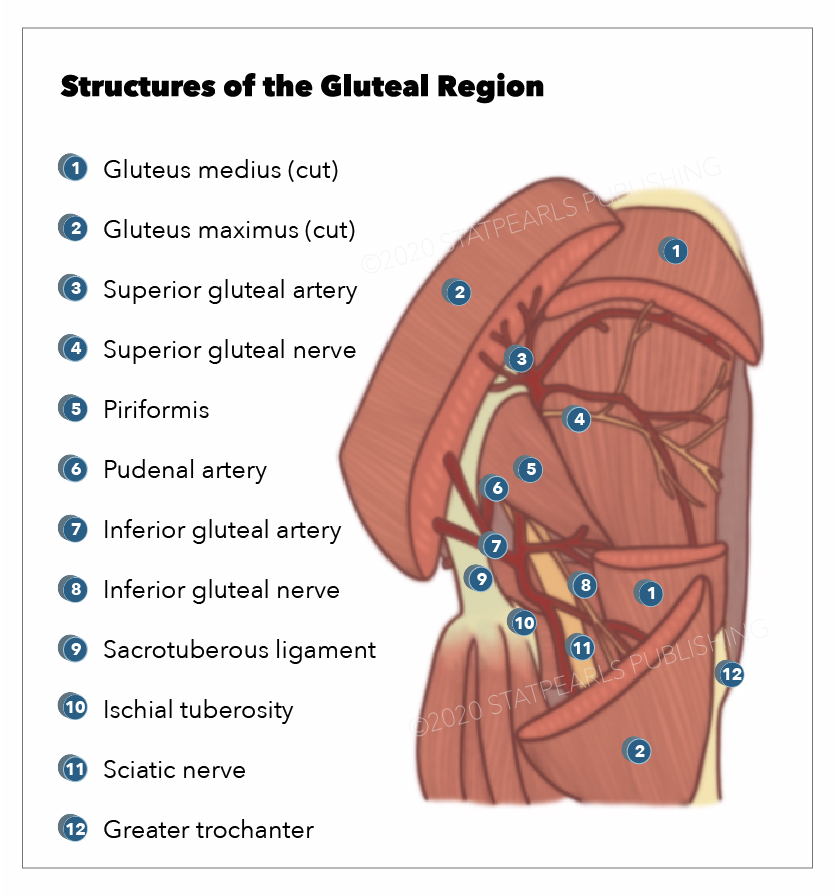

The inferior gluteal nerve branches off the sacral plexus. The nerve's short path primarily serves to innervate the gluteus maximus muscle. The composition of this nerve is from the dorsal branches of the ventral rami of the fifth lumbar and the first two sacral nerves.[1]

The inferior gluteal nerve courses inferiorly and medially before exiting the pelvic cavity via the greater sciatic notch. After exiting the notch, the inferior gluteal nerve passes inferior to the piriformis muscle belly before dividing into several muscular branches supplying the gluteus maximus.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The inferior gluteal nerve is a motor nerve responsible for the motor activity of the gluteus maximus muscle. The muscle is primarily responsible for the extension of the trunk from a forward bending position and extension of the hip from sitting to standing and during stair climbing.[2] Some evidence has shown that the gluteus maximus muscle plays a more important role in running than walking, creating an argument that humans evolved to run.[3]

Embryology

The inferior gluteal nerve is part of the peripheral nervous system and is formed by the neural crest cells. During early vertebrate development, the neural crest cells develop between the neural plate and the non-neural ectoderm. The neural plate will eventually become the central nervous system; the ectoderm will become the epidermis, leaving the neural crest contributing to the peripheral nervous system.[4] The inferior gluteal nerve is a component of the sacral plexus and carries divisions of the fifth lumbar through the second sacral.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The inferior gluteal artery, a branch of the internal iliac, accompanies the inferior gluteal nerve as it innervates the gluteus maximus. The superior and inferior gluteal lymph nodes supply the gluteal region of the pelvis. These superior and inferior gluteal lymph nodes are parietal progressions of the internal iliac lymph vessels.[5]

The gluteal artery and vein have been localized. A point one-third of the distance between the mid-sacral border and the greater trochanter was used as a reference point. The superior gluteal vein averaged 3.28 cm away from this point, and the inferior gluteal vein averaged 1.25 cm from this point. These localizations are useful in enabling safe surgery on the buttock.[6]

Nerves

Other nerves originating from the same plexus are the superior gluteal nerve, inferior gluteal nerve, common fibular, tibial, posterior femoral cutaneous, pudendal, and sciatic. The sciatic nerve is the largest of these and will have multiple branches before its termination. The sciatic nerve is important because of its size and the neurological and orthopedic pathology affecting it. Injury to the sciatic nerve often presents with hamstring motor deficits in conjunction with a sensory deficit of the posterior thigh. A more complex manifestation of sciatic nerve involvement can occur in cauda equina syndrome when its nerve roots are affected.[7]

Muscles

The inferior gluteal nerve innervates the gluteus maximus muscle. This muscle is primarily responsible for hip and torso extension and returning from a squatting position. The gluteus maximus muscle has a broad base of origin from the posterior surface of the iliac crest down to the lateral border of the coccyx with fascial insertion onto the sacral multifidus and the gluteus medius and inserts itself into the gluteal tuberosity of the femur and portions of the iliotibial fascia. Bartlett and colleagues examined the gluteus maximus muscle during different active movements and found that sprinting far superseded climbing, walking, and running. They compared this muscular pattern to that of apes and found that with different insertional patterns, humans had more gluteus maximus activation during sprinting, suggesting an evolutionary adaptation.[8]

The gluteus maximus is a powerful extensor of the thigh at the hip. Pathology involving the gluteus maximus will manifest in two specific situations. Patients will exhibit difficulty in walking up stairs. The gluteus maximus is responsible for levering the patient up to the next stair level. The flexion of the thigh at the hip and the leg at the knee involved in raising the foot to the next stair level involves the quadriceps femoris innervated by the femoral nerve. A second situation involving the gluteus maximus occurs when arising from a chair. These actions utilize the ability to extend the thigh at the hip in a powerful manner.

Another aspect of the gluteus maximus often omitted is its role in power extension during pelvic thrusting in sexual intercourse.

Physiologic Variants

Some studies have examined variations in the course of the inferior gluteal nerve. Tillman found in 112 subjects, 17 had the inferior gluteal nerve pass through the piriformis, similar to the variations seen with the sciatic nerve. They observed that this variation was more common in men.[9]

In a rare case from Sumalatha et al, the inferior gluteal nerve was absent, and a division of the common peroneal nerve innervated the gluteus maximus. Although most anatomy textbooks will show the inferior gluteal nerve passing below the piriformis, the inferior gluteal nerve will pass superiorly to the piriformis in approximately 0.2% to 4.4% of the adult population.[10]

Variations in the Inferior Gluteal Nerve

There is a report of a variant of the sciatic nerve and the inferior gluteal nerve. The right inferior gluteal nerve was very thick. The inferior gluteal nerve was a branch of the common fibular nerve. Intramuscular injections to treat a spastic piriformis muscle for piriformis syndrome make injections in the sciatic and inferior gluteal nerve potentially very important and even dangerous because of these variations.[11]

A case of congenital absence of the inferior gluteal nerve has been reported.[10] The common fibular nerve pierced the piriformis muscle, innervating it and emerging to form the thin medial trunk and a much thicker lateral trunk. Again, these variations are important in deep gluteal space injections, such as in an injection of the piriformis muscle. Other considerations are nerve block injury during operations on the posterior hip.

Bilateral variations in the sciatic nerve have been described in which the common fibular nerve exited above the piriformis muscle, and the tibial nerve division exited below the piriformis on the right and then joined the tibial division.[12]

Surgical Considerations

Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA)

Posterolateral Approach

One of the most common surgical approaches total joint replacement surgeons prefer is the posterolateral approach. This dissection does not utilize a true inter-nervous plane. The intermuscular interval involves blunt dissection of the gluteus maximus fibers proximally and a sharp incision of the fascia lata distally. The deep dissection involves a meticulous dissection of the short external rotators and the hip joint capsule. Care is necessary to protect these structures, which are later repaired back to the proximal femur via trans-osseous tunnels.[13]

Peripheral Nerve Injury in THA

Multiple studies have reported the incidence rates and overall risk of peripheral nerve injuries during the most common THA approaches. The incidence rates reported vary widely in the literature. Reports dating back to the 1980s and 1990s cited up to an 8% incidence rate in THA patients.[14] More contemporary studies report a 0.6% to 3.7% risk of nerve injury in THA patients, with the incidence rate at least doubled in the revision setting.[15] The latter has much documentation in the literature dating back to the early 1970s.[16][17]

Inferior Gluteal Nerve Considerations

While most literature reports focus on injury to the sciatic, femoral, obturator, superior gluteal, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves, much less attention is given to the inferior gluteal nerve. The exact clinical outcome "definition" varies significantly from study to study. Fortunately, the majority of nerve injuries are relatively mild (ie, mild neuropraxia). However. the postoperative clinical examination likely underestimates the true incidence of neurologic injuries following THA; this is particularly true in the case of the inferior gluteal nerve.

Multiple cadaveric studies have documented the anatomy and course of the inferior gluteal nerve concerning its anatomic susceptibility during the posterolateral approach to the hip. Apaydin et al used 36 cadavers to develop a triangular landmark for the inferior gluteal nerve, including the posterior inferior iliac spine, ischial tuberosity, and greater trochanter.[18]

Other Technical Considerations

While many authors support the utilization of minimal invasive THA techniques, the potential benefits of these procedures can only truly achieve clinical fruition with superior knowledge of nerve anatomy, as trading the benefits of superior visualization during these procedures can potentially be offset by an increased risk of iatrogenic neurovascular injuries.

Techniques to reduce the likelihood of nerve compromise are achievable. One way is through a more minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty, where the surgeon does not dissect the gluteus maximus tendon and removes less tissue, significantly reducing nerve compromise.[19] That said, superior knowledge of the course of the nerve requires mastery.

Marcy et al describe a different approach to the hip. They do not split the gluteus maximus but only retract the muscle backward with little damage to the nerve. This technique, however, has its disadvantages. It requires significant mobilization of the muscles and is, therefore, labor-intensive.[20] The more preferred approach involves splitting the gluteus maximus muscles. The incision must be 5 mm or less from the tip of the greater trochanter and extend approximately 10 cm along the iliotibial tract. This route will protect the inferior gluteal nerve.

Clinical Significance

Sciatica

The sciatic nerve is typically the focus in piriformis syndrome, but any structure passing through the infra-piriform foramen can be compromised, including the inferior gluteal nerve. Inferior gluteal nerve entrapment will have primary signs of gluteus maximus atrophy.[21]

The Seddon and Sunderland classification of peripheral nerve compromise is a valuable tool for testing a neurological injury. Seddon and Sunderland create five main classes of nerve compromise; neurapraxia, axonotmesis I-III, and neurotmesis. During neurapraxia, focal demyelination occurs. This is the least severe state and usually has the best chance of full recovery. Axonotmesis is a more progressive stage of nerve injury that involves the axon.

Progression from axonotmesis grade I to III involves the surrounding endoneurium and perineurium. This stage can heal, but it is less likely to do so. Neurotmesis is the most severe stage. This stage typically involves complete transection and is usually the stage that involves post-surgical compromise. Most of these conditions do not fully heal without surgical correction.[22] The preferred treatment for these issues utilizes an end-to-end repair of the severed nerve. Kretschmer et al reported a good recovery in 70% post-surgical repair of iatrogenic nerve damage.[23]

Sciatica involves pain that originates in the sacral plexus and passes down the posterior portion of the lower limb. Compression of the extra-spinal portions of the sciatic nerve can mimic sciatica due to a herniated lumbar disc. Pathology involving the hip and sacroiliac joints can produce lumbar pain.[24] For many years sciatica was thought to be due to a herniated lumbar disc. This is certainly true; however, piriformis syndrome can mimic sciatic neuropathy.[25]

Sciatic nerve damage results in pain on sitting, radicular pain involving the hip or lower back, and paresthesias affecting the leg and foot. Abnormal reflexes or motor weakness may be present.[26]

Piriformis Syndrome

The piriformis muscle arises from segments S2-S4 of the sacrum, the anterior sacrospinous ligament, the sacroiliac joint, and the sacrotuberous ligament. It exits the greater sciatic foramen to insert onto the femur on the greater trochanter.[25]

The most common symptoms of the piriformis syndrome are buttock pain, aggravation of pain upon sitting and relief from standing, sciatic notch tenderness, and increased pain with specific maneuvers designed to diagnose piriformis, such as the FAIR test, Pace test, etc.[25] The gluteus maximus is innervated by the inferior gluteal nerve. Some of the pain in the buttock may arise from the inferior gluteal nerve as myogenic pain.

Two types of piriformis syndrome can be distinguished: primary piriformis syndrome due to the piriformis itself and secondary piriformis syndrome due to a discrepancy between the length of the legs, fibromyalgia, congenital variation in the length of the piriformis and the sciatic nerve, or spinal stenosis.[24] Synonyms for the piriformis syndrome are deep gluteal space syndrome, extra-spinal sciatica, and wallet neuritis.[27]

Corticosteroid injection diminishes the pain of piriformis syndrome.[27]

Wallet Neuritis Syndrome

Wallet neuritis (sitting with a fat wallet in the back pocket) can mimic piriformis syndrome, even though neurological tests for piriformis syndrome, such as flexion, adduction, internal rotation (FAIR test), and Pace sign, may be absent. Wallet neuritis is an extra-spinal neuropathy that causes gluteal and lower extremity pain involving the ipsilateral side of the body.[28]

Deep Gluteal Space Syndrome

Deep gluteal syndrome involves gluteal pain from extra-pelvic entrapment of the sciatic nerve due to non-discogenic sciatic nerve entrapment. Extra-spinal lesions of the sciatic nerve can confound the diagnosis of sciatic nerve lesions.[24] These extra-spinal lesions include piriformis syndrome, quadratus lumborum syndrome, osteitis ilii, and cluneal disorder. Thus according to some authors, the term deep gluteal space now incorporates the piriformis, even though other authors treat the piriformis as a separate entity.

The boundaries of the deep gluteal space are as follows.[26]

- Anterior boundary: hip joint capsule, proximal femur, and posterior acetabular column

- Posterior boundary: gluteus maximus and inferior gluteal nerve

- Lateral boundary: lateral lip of the linea aspera and gluteal tuberosity

- Medial boundary: falciform fascia and sacrotuberous ligament

- Superior boundary: sciatic notch and the adjacent osseous margin

- Inferiorly: the origin of the hamstring muscles from the ischial tuberosity

The contents of the deep gluteal space are the piriformis muscle, the hamstring muscles, the vascular system, and the gemelli-obturator complex.[26] Problems associated with the deep gluteal space include piriformis syndrome, fibrous bands associated with the sciatic nerve, and ischiofemoral impingement.[29]

The greater sciatic foramen contains several structures, some of which may be involved in the deep gluteal space syndrome. These are the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve, superior gluteal nerve, inferior gluteal nerve, nerve to the obturator internus, nerve to the quadratus femoris, pudendal nerve, and sciatic nerve.

The most common symptoms of deep gluteal space syndrome include buttock pain, sciatic pain, intolerance to sitting, loss of sensation over the lower extremity, limping, lumbar pain, and night pain.

Tests that may be useful in diagnosing the deep gluteal space syndrome include the anterior/seated piriformis test, Lasegue test, Freiberg sign, Beatty sign, Pace sign, and the FAIR test.

The deep gluteal space may be surgically accessed with an endoscopic or open surgical approach.[30][26]

Other Issues

Perisacral surgical techniques offer a different type of difficulty. During peri-sacral surgery to remove tumors, the surgeon must have clear landmarks developed or risk cutting the superior and or inferior gluteal artery. The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments are landmarks that the surgeon must identify because these two ligaments lie over the superior and inferior gluteal arteries. Traditional surgical techniques removed more gluteus tissue, which made identification of the arteries easier, but also compromised functional recovery because of tissue loss.[31]

Media

References

Craig A. Entrapment neuropathies of the lower extremity. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2013 May:5(5 Suppl):S31-40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.03.029. Epub 2013 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 23542774]

Ling ZX, Kumar VP. The course of the inferior gluteal nerve in the posterior approach to the hip. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2006 Dec:88(12):1580-3 [PubMed PMID: 17159167]

Lieberman DE, Raichlen DA, Pontzer H, Bramble DM, Cutright-Smith E. The human gluteus maximus and its role in running. The Journal of experimental biology. 2006 Jun:209(Pt 11):2143-55 [PubMed PMID: 16709916]

Bronner ME. Formation and migration of neural crest cells in the vertebrate embryo. Histochemistry and cell biology. 2012 Aug:138(2):179-86. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-0999-z. Epub 2012 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 22820859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUzun Ç, Erden A, Düşünceli Atman E, Üstüner E. Use of MRI to identify enlarged inferior gluteal and ischioanal lymph nodes and associated findings related to the primary disease. Diagnostic and interventional radiology (Ankara, Turkey). 2016 Jul-Aug:22(4):314-8. doi: 10.5152/dir.2016.15478. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27113423]

Muresan C, Davis JM, Hiller AR, Patterson BE, Kapsalis CN, Ford MF, Anderson EW, Kachare SD, Hazani R, Wilhelmi BJ. The Safe Gluteoplasty: Anatomic Landmarks to Predict the Superior and Inferior Gluteal Veins. Eplasty. 2019:19():e8 [PubMed PMID: 30949281]

Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T. Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2011 May:20(5):690-7. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1668-3. Epub 2010 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 21193933]

Bartlett JL, Sumner B, Ellis RG, Kram R. Activity and functions of the human gluteal muscles in walking, running, sprinting, and climbing. American journal of physical anthropology. 2014 Jan:153(1):124-31. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22419. Epub 2013 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 24218079]

Tillmann B. [Variations in the pathway of the inferior gluteal nerve (author's transl)]. Anatomischer Anzeiger. 1979:145(3):293-302 [PubMed PMID: 474994]

Sumalatha S, D Souza AS, Yadav JS, Mittal SK, Singh A, Kotian SR. An unorthodox innervation of the gluteus maximus muscle and other associated variations: A case report. The Australasian medical journal. 2014:7(10):419-22. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2014.2225. Epub 2014 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 25379064]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGolmohammadi R, Delbari A. Report of a Novel Bilateral Variation of Sciatic and Inferior Gluteal Nerve: A Case Study. Basic and clinical neuroscience. 2021 May-Jun:12(3):421-426. doi: 10.32598/bcn.2021.1900.1. Epub 2021 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 34917300]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceButz JJ, Raman DV, Viswanath S. A unique case of bilateral sciatic nerve variation within the gluteal compartment and associated clinical ramifications. The Australasian medical journal. 2015:8(1):24-7. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2015.2266. Epub 2015 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 25848405]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVaracallo M, Luo TD, Johanson NA. Total Hip Arthroplasty Techniques. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939641]

Abitbol JJ, Gendron D, Laurin CA, Beaulieu MA. Gluteal nerve damage following total hip arthroplasty. A prospective analysis. The Journal of arthroplasty. 1990 Dec:5(4):319-22 [PubMed PMID: 2290087]

Hasija R, Kelly JJ, Shah NV, Newman JM, Chan JJ, Robinson J, Maheshwari AV. Nerve injuries associated with total hip arthroplasty. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2018 Jan-Mar:9(1):81-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.10.011. Epub 2017 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 29628688]

Weber ER, Daube JR, Coventry MB. Peripheral neuropathies associated with total hip arthroplasty. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1976 Jan:58(1):66-9 [PubMed PMID: 175071]

Johanson NA, Pellicci PM, Tsairis P, Salvati EA. Nerve injury in total hip arthroplasty. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1983 Oct:(179):214-22 [PubMed PMID: 6617020]

Apaydin N, Bozkurt M, Loukas M, Tubbs RS, Esmer AF. The course of the inferior gluteal nerve and surgical landmarks for its localization during posterior approaches to hip. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2009 Jul:31(6):415-8. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0459-6. Epub 2009 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 19190851]

Sculco TP, Boettner F. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: the posterior approach. Instructional course lectures. 2006:55():205-14 [PubMed PMID: 16958456]

MARCY GH, FLETCHER RS. Modification of the posterolateral approach to the hip for insertion of femoral-head prosthesis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1954 Jan:36-A(1):142-3 [PubMed PMID: 13130602]

Grgić V. [Piriformis muscle syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and therapy]. Lijecnicki vjesnik. 2013 Jan-Feb:135(1-2):33-40 [PubMed PMID: 23607175]

Menorca RM, Fussell TS, Elfar JC. Nerve physiology: mechanisms of injury and recovery. Hand clinics. 2013 Aug:29(3):317-30. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2013.04.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23895713]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKretschmer T, Antoniadis G, Braun V, Rath SA, Richter HP. Evaluation of iatrogenic lesions in 722 surgically treated cases of peripheral nerve trauma. Journal of neurosurgery. 2001 Jun:94(6):905-12 [PubMed PMID: 11409518]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSiddiq MAB, Clegg D, Hasan SA, Rasker JJ. Extra-spinal sciatica and sciatica mimics: a scoping review. The Korean journal of pain. 2020 Oct 1:33(4):305-317. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2020.33.4.305. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32989195]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHopayian K, Song F, Riera R, Sambandan S. The clinical features of the piriformis syndrome: a systematic review. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2010 Dec:19(12):2095-109. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1504-9. Epub 2010 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 20596735]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMartin HD, Reddy M, Gómez-Hoyos J. Deep gluteal syndrome. Journal of hip preservation surgery. 2015 Jul:2(2):99-107. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnv029. Epub 2015 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 27011826]

Siddiq MAB. Piriformis Syndrome and Wallet Neuritis: Are They the Same? Cureus. 2018 May 10:10(5):e2606. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2606. Epub 2018 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 30013870]

Siddiq MAB, Jahan I, Masihuzzaman S. Wallet Neuritis - An Example of Peripheral Sensitization. Current rheumatology reviews. 2018:14(3):279-283. doi: 10.2174/1573397113666170310100851. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28294069]

Carro LP, Hernando MF, Cerezal L, Navarro IS, Fernandez AA, Castillo AO. Deep gluteal space problems: piriformis syndrome, ischiofemoral impingement and sciatic nerve release. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2016 Jul-Sep:6(3):384-396. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2016.6.3.384. Epub 2016 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 28066745]

Ham DH, Chung WC, Jung DU. Effectiveness of Endoscopic Sciatic Nerve Decompression for the Treatment of Deep Gluteal Syndrome. Hip & pelvis. 2018 Mar:30(1):29-36. doi: 10.5371/hp.2018.30.1.29. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29564295]

Kieser DC, Coudert P, Cawley DT, Gaignard E, Fujishiro T, Farah K, Boissiere L, Obeid I, Pointillart V, Vital JM, Gille O. Identifying the superior and inferior gluteal arteries during a sacrectomy via a posterior approach. Journal of spine surgery (Hong Kong). 2017 Dec:3(4):624-629. doi: 10.21037/jss.2017.12.06. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29354741]