Introduction

Page kidney or Page phenomenon results from external compression of the kidney and is a rare, treatable cause of secondary hypertension that is mediated by activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS).[1] The workup of a young patient with hypertension, defined as high blood pressure in a patient younger than 30, is comprised of extensive investigations to rule out a secondary cause. However, a sharp rise in the prevalence of hypertension in the young has been observed, doubling over the last decade, and most often a diagnosis of essential/primary hypertension is made. As there is an ever-rising burden on healthcare costs, it is recommended in the guidance that the routine workup of such patients is limited to a basic set of investigations. Specialized investigations, such as renal imaging, should only be kept for cases where there is a clinical suspicion of underlying secondary pathology. In most places, renal ultrasound is still included in baseline investigations; however, sometimes it is sparingly available. Therefore young patients are frequently diagnosed with essential/primary hypertension causing a delay in the diagnosis of secondary hypertension.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

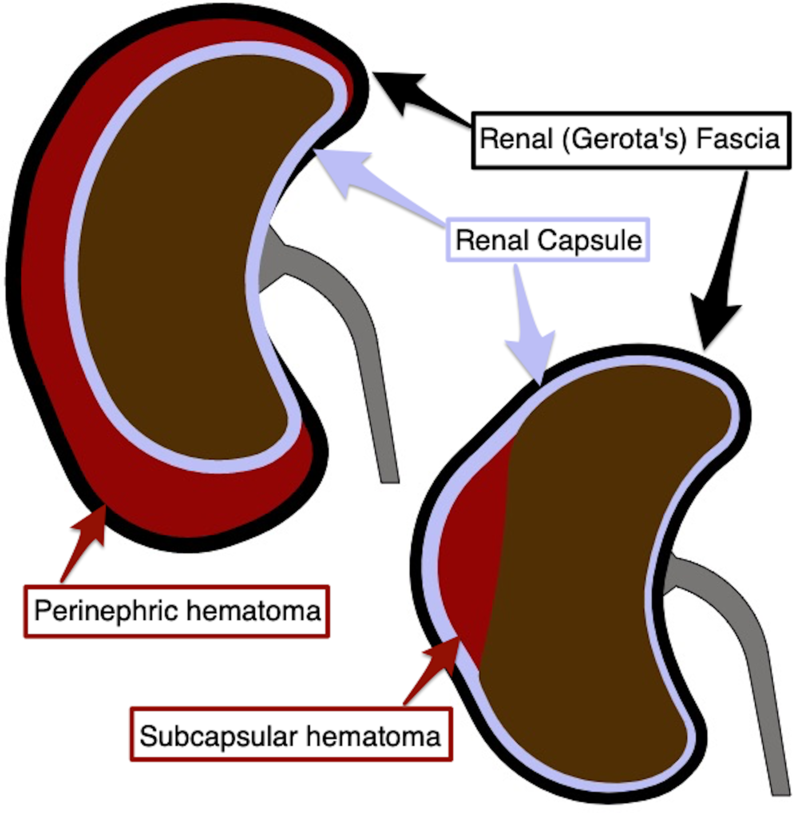

The kidneys are surrounded by a smooth, tough fibrous capsule that has limited space and a small amount of fluid under the capsule can cause compression of the kidney parenchyma resulting in Page kidney. Gerota fascia, on the other hand, is a larger space and can accommodate a considerable amount of blood or fluid before kidney parenchyma is compressed. In most cases of Page kidney, the compression causing hypertension is extracapsular. See Image. Page Kidney, Computed Tomography Scan.

External compression of the kidney may be due to a collection of blood or from some other source. Bleeding around the kidney may result from the following:

- Blunt trauma: sports injuries like football, hockey, other contact sports, motor vehicle accidents, violence, or fall

- Iatrogenic: following biopsy of native or transplant kidney, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, ureteral surgery, sympathetic nerve block

- Spontaneous: anticoagulation, arterioventral malformation, tumor, vasculitis, pancreatitis

Non-bleeding causes of external compression include lymphoceles, particularly around the transplanted kidney, urinoma, retroperitoneal paraganglioma, or large simple cysts.[1][2] The iatrogenic or traumatic subcapsular hematoma has been observed to be the most commonly found cause of Page kidney (see Image. Renal Hematoma).[3] Previously, many cases were attributed to sports-related trauma such as football or non-sports-related blunt trauma of the abdomen, referred to as classic Page kidney.[4] Assessment of cases published after 1991 demonstrated an etiological switch towards the iatrogenic subcapsular hematoma.[2] These most frequently occurred as complications of performing a biopsy of renal allograft but also resulted from extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy or other procedures such as ureteronephroscopy.[5]

Non-traumatic or spontaneous causes of Page kidney are rare with isolated cases occasionally reported in the literature. The causes generally include spontaneous renal hemorrhage because of arteriovenous malformations, underlying tumors, cyst rupture, vasculitis, or glomerulonephritis. Lymphatic collections and subcapsular urinomas have also been observed. In some rare cases, Page kidney could be idiopathic.[3][4]

Epidemiology

In the older literature, the typical patient was a young, healthy male athlete who presented with hypertension and who had a sports-related injury in the past. In recent years, the majority of cases have been iatrogenic and related to procedures or operations that are done on or around kidneys and reported to occur at all ages.

Pathophysiology

Irvine Page first described this entity in 1939. He performed animal experiments in which he wrapped the kidneys in cellophane. An intense inflammatory response followed and produced a fibrocollagenous shell that compressed the kidney. Compression of intrarenal vessels led to ischemia and activation of RAAS. Hypertension developed within 4 to 5 weeks and was cured by nephrectomy of the affected kidney.[1][6] In 1955, Engel and Page described the first case of Page kidney in a 19-year-old football player with a 2-year history of hypertension who had sustained flank trauma two years earlier and who was found to have a subcapsular hematoma. Hypertension was cured after nephrectomy.

Hypertension in the Page kidney is mediated by activation of RAAS and the mechanism of hypertension is similar to Goldblatt hypertension. Goldblatt, in his experiments, applied clamps to the main renal artery to reduce blood flow. Hypoperfusion of the kidneys leads to the release of renin, and activation of RAAS which leads to hypertension. In the Page kidney, external compression of the kidney leads to decreased perfusion in intrarenal blood vessels. Resultant microvascular ischemia causes activation of RAAS leading to hypertension.[2]

Proof of RAAS dependence of hypertension in this entity is suggested by the following:

- Elevated plasma renin activity

- Elevated renin level in the venous effluent from the affected kidney

- Response of blood pressure to Saralasin infusion

- Normalization of blood pressure following nephrectomy of the affected kidney

History and Physical

The presentation of Page kidney may range from non-specific clinical presentation with an insidious onset, to a catastrophic event of hypertensive urgency or emergency.[7] Page kidney must always be considered in young patients with high blood pressure presenting with a renal mass or a history of abdominal trauma. Hypertension is the main manifestation of the Page kidney and may develop rapidly after the causative event or may be slow in onset and occur a long time after the causative event. The history of trauma may not be obvious. In cases of recent perinephric bleeding, a flank hematoma may be seen. Otherwise, there are no significant abnormalities on physical examination in patients with Page kidney except for hypertension.

Ultrasound of the kidneys and contrast-enhanced computed tomography is generally adequate in making a diagnosis of Page kidney.[3] Renal function is typically normal if compression of the kidney is unilateral since the contralateral normal kidney can compensate. Renal function may be impaired if the external renal compression is bilateral or there is compression of a single functioning kidney, eg, transplant kidney. The providers need to remember that a significant time lapse could be seen between trauma and the diagnosis of hypertension. The interval could range between days and decades, as has been reported in many cases. The traumatic event may even go unnoticed.

Evaluation

Page kidney is most often diagnosed based on imaging studies. Ultrasonography and computed tomography of the kidneys are the most frequently used modalities. Ultrasound has the advantage of being cheap, quick, easy to perform, easily available, and noninvasive. However, it can miss small subcapsular hematoma. CT scan of the abdomen has similar advantages and has the benefit of being able to detect small hematomas and is most frequently used.[3][8] Renal vein renin determination can certainly prove activation of RAAS as the causative mechanism of hypertension but is frequently not done.

Treatment / Management

Previously, radical nephrectomy or open surgery were the mainstays of management of classical Page kidney. With medical improvements in anti-hypertensive medications, particularly those that act against the RAAS, the management of Page kidney has shifted to a rather conservative approach.[2] Activation of RAAS mediates hypertension in this condition, and hence the ideal agents for the treatment of hypertension are RAAS blockers.[6] Medical treatment of hypertension may be required for a short period if the cause of renal compression resolves spontaneously or following intervention, for instance, resorption or evacuation of subcapsular hematoma. Intervention may be needed for larger, symptomatic, or enlarging collections or those with poorly controlled hypertension. The 2 main goals of intervention are renal decompression by the evacuation of the hematoma and the removal of the fibrocollagenous pseudocapsule, which can form in chronic cases.[9] This may require open or percutaneous drainage of the compressing collection. If the collection has been long-standing, a fibrocollagenous shell may have formed, and this may require decapsulation of this shell or even nephrectomy.(B3)

It has been shown by recent case reports that minimally invasive procedures, for instance, laparoscopy- or radiology-assisted percutaneous drainage are viable therapeutic alternatives.[5] Percutaneous drainage has been observed to have better success rates in subcapsular hematomas that are less than 3 weeks in duration. However, more chronic organized hematomas frequently require invasive procedures for sufficient evacuation.[5] In patients with lymphangiomatosis, the preferred management option becomes percutaneous drainage with the injection of sclerosing agents.[10] Elevation of blood pressure is permanent in some cases, and lifelong antihypertensive drug therapy may be needed.[4][11] Still, there is no standardization in the definitive management of Page kidney, as it depends on several patient factors, as well as the underlying pathology.[5](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

If the history of flank trauma is not available and the patient presents with hypertension, it would be impossible to diagnose Page kidney because there are no unique physical findings to suggest the disease. Imaging is the way to identify the disease. Elevated renin level indicates RAAS activation as the cause of hypertension and may be due to renal artery stenosis, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, or malignant hypertension. Differentials also include acute rejection, acute tubular necrosis, and renal vein thrombosis.

Prognosis

The exact percentage of mortality or long-term morbidity is still not known but some cases resolve spontaneously without the need for surgical treatment. Often, appropriate medical therapy is needed and may be successful as a spontaneous resolution could be delayed or not happen at all.[12]

Complications

Following are some important complications that the providers should be aware of while dealing with a patient with Page kidney:

- Persistent hypertension

- Renal failure

- Loss of renal allograft

- Hematuria

Deterrence and Patient Education

Every surgical procedure or interventional investigation comes with a set of adverse outcomes and Page kidney is an example of this phenomenon. Patients and their families should be made aware in detail by the interprofessional team regarding the possible adverse outcomes of undergoing transplant surgery or renal biopsy. Education should be given to the patients who have developed the Page kidney so that medical management can help resolve the complication spontaneously. In other cases, surgery may be needed.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Page kidney is a rare but potentially treatable and curable form of hypertension and requires awareness of the entity by primary care providers, nephrologists, and other providers. Close coordination of care is required with radiologists in making the diagnosis and with urologists in providing urological options like percutaneous drainage or capsulectomy which may improve or cure hypertension.[2][4][9]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Renal Hematoma. The image depicts renal hematoma with relevant anatomy.

Walkermangin, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Haydar A, Bakri RS, Prime M, Goldsmith DJ. Page kidney--a review of the literature. Journal of nephrology. 2003 May-Jun:16(3):329-33 [PubMed PMID: 12832730]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDopson SJ, Jayakumar S, Velez JC. Page kidney as a rare cause of hypertension: case report and review of the literature. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2009 Aug:54(2):334-9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.014. Epub 2009 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 19167799]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArslan S. Bilateral nontraumatic recurrent Page kidney. Radiology case reports. 2017 Sep:12(3):511-513. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2017.05.003. Epub 2017 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 28828114]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmyth A, Collins CS, Thorsteinsdottir B, Madsen BE, Oliveira GH, Kane G, Garovic VD. Page kidney: etiology, renal function outcomes and risk for future hypertension. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.). 2012 Apr:14(4):216-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00601.x. Epub 2012 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 22458742]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKobel MC, Nielsen TK, Graumann O. Acute renal failure and arterial hypertension due to subcapsular haematoma: is percutaneous drainage a feasible treatment? BMJ case reports. 2016 Jan 18:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212769. Epub 2016 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 26783007]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWahdat R, Schwartz C, Espinosa J, Lucerna A. Page kidney: taking a page from history. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Jan:35(1):193.e1-193.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.095. Epub 2016 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 27439385]

Kenis I, Werner M, Nacasch N, Korzets Z. Recurrent non-traumatic page kidney. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2012 Jul:14(7):452-3 [PubMed PMID: 22953625]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiczek M, Udayasankar U. Page Kidney. The Journal of urology. 2015 Oct:194(4):1109-10. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.07.035. Epub 2015 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 26173105]

Davies MC, Perry MJ. Urological management of 'page kidney'. BJU international. 2006 Nov:98(5):943-4 [PubMed PMID: 17034594]

Choudhury S, Sridhar K, Pal DK. Renal lymphangiectasia treated with percutaneous drainage and sclerotherapy. International journal of adolescent medicine and health. 2017 Jun 9:31(4):. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0024. Epub 2017 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 28598807]

Whitworth PW 3rd, Dyer RB. The "Page kidney". Abdominal radiology (New York). 2017 Sep:42(9):2387-2388. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1139-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28393300]

Myrianthefs P, Aravosita P, Tokta R, Louizou L, Boutzouka E, Baltopoulos G. Resolution of Page kidney-related hypertension with medical therapy: a case report. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2007 Sep-Oct:36(5):377-9 [PubMed PMID: 17845884]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence