Introduction

Physical examination plays a crucial role in patient diagnosis and is essential to every clinical patient encounter with the treating clinician. An abdominal examination provides diagnostic clues regarding most gastrointestinal and genitourinary pathologies and may offer insight into abnormalities in other organ systems. In clinical assessment, the usual sequence involves obtaining the patient's history first, followed by a physical examination. However, in emergency situations, history may take less precedence. A well-performed abdominal examination decreases the need for imaging and facilitates patient management.

Several aspects of the standardized abdominal examination utilize eponyms, most commonly the Kehr, Grey Turner, or Cullen signs. These signs have limited demonstrated sensitivity or specificity and mainly serve to honor the physicians who discovered them.[1] Similarly, parts of the abdominal examination, such as percussion, are debated as to whether positive findings could determine any diagnosis.[2] As the theoretical debates continue, further research is needed concerning the validity of these historical parts of the abdominal examination.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

The abdominal examination is performed with the patient lying supine. The clinician should begin by giving a formal introduction and approaching the patient from the right side. The initial steps are as follows:

- Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water. An alcohol-based sanitizer is recommended.

- Identify the patient.

- Briefly explain the purpose and steps of the examination and obtain the patient's consent.

- Inquire if the patient has any pain.

- Position the patient. The patient is initially positioned at 45° for comfort, but a supine position is necessary to palpate the abdomen. Keeping a pillow under the patient's head or knees can be considered.

- Ideally, the exposure should be from the nipples to the knees, but this is not practical sometimes. During most clinical examinations, the exposure is from the nipples to the lower abdomen.[3]

Visual Assessment

Begin with a general inspection of the patient and then proceed to the abdominal area. This examination typically occurs at the foot end of the bed. The visual assessment can give multiple clues regarding the patient's diagnosis; for example, yellowish skin discoloration (jaundice) indicates a possible hepatic abnormality. Any medical equipment should be noted for monitoring and treatment purposes, including catheters, pulse oximeters, oxygen masks and tubing, nasogastric tubes, central lines, and total parenteral nutrition lines.

Examination of the Hands and Arms

The hands should be examined for the presence of pallor and jaundice. The outstretched hands are observed for the presence of tremors. A flapping tremor (asterixis) indicates hepatic encephalopathy and may be present in cirrhosis.[4] A nonspecific tremor may also indicate alcohol withdrawal. The radial pulse should be examined, and the blood pressure should be recorded. The hands and arms should be examined for evidence of intravenous drug use, which may be present as injection site marks. An arteriovenous fistula indicates renal replacement therapy and should be inspected and palpated.

Examination of the Face and Neck

The examination should begin by asking the patient to look straight ahead. The eyes should be examined for scleral icterus and conjunctival pallor. Additional findings may include a Kayser-Fleischer ring, a brownish-green ring at the periphery of the cornea observed in patients with Wilson disease due to excess copper deposited at the Descemet membrane.[5] The ring is best viewed under a slit lamp. Periorbital plaques, called xanthelasmas, may be present in chronic cholestasis due to lipid deposition. Angular cheilitis, inflammatory lesions around the corner of the mouth, indicate iron or vitamin deficiency, possibly due to malabsorption.[6] Depending on the clinician's judgment, the oral cavity could be examined in detail. The presence of oral ulcers may indicate Crohn or celiac disease. A pale, smooth, shiny tongue suggests iron deficiency, and a beefy, red tongue is observed in vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies. The patient's breath smells indicate different disorders, such as fetor hepaticus, a distinctive smell indicating liver disorder, or a fruity breath pointing towards ketonemia. The clinician should stand behind the patient to examine the neck. Palpating for lymphadenopathy in the neck and the supraclavicular region is important. The presence of the Virchow node may indicate the possibility of gastric or breast cancer.[7]

Basic Components of Abdominal Examination

Following a quick assessment, the abdominal examination consists of 4 basic components—inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

Inspection of the abdomen: The general examination of the abdomen begins with the patient in a completely supine position. The presence of any of the following signs may indicate specific disorders. Distension of the abdomen could be present due to conditions such as small bowel obstruction, masses, tumors, cancer, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, constipation, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and pregnancy. Any abnormal masses may indicate an umbilical hernia, ventral wall hernia, femoral hernia, or inguinal hernia, depending on the location. The patient may be instructed to cough, which results in raised intra-abdominal pressure, causing any hernias to become more prominent.

Upon inspection, a patch of ecchymosis may be visible on any part of the abdomen and typically indicates internal hemorrhage. The Grey Turner sign is the ecchymosis of the flank and groin observed in hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and the Cullen sign is a periumbilical ecchymosis from retroperitoneal hemorrhage or intra-abdominal hemorrhage. The presence of scars may be due to surgical or traumatic injuries, such as gunshot wounds or stab wounds, and pink-purple striae may indicate Cushing syndrome. Vein dilation may be present that indicates portal hypertension or vena cava obstruction. Caput medusa describes veins flowing away from the umbilicus, with a 90% specificity for detecting hepatic cirrhosis.[8] Sinuses and fistulae, if present, typically occur due to deep infection or an infection of a surgical tract. If a stoma is present, various characteristics should be noted to determine the type of stoma, including its size, appearance, and the contents of the stoma bag.

Auscultation of the abdomen: The next step in the abdominal examination is auscultation with a stethoscope. The stethoscope's diaphragm should be placed on the right side of the umbilicus to listen to the bowel sounds, and the rate should be calculated after listening for at least 2 minutes. Normal bowel sounds are low-pitched and gurgling; the rate is normally 2 to 5 sounds/minute. The absence of bowel sounds may indicate paralytic ileus, whereas hyperactive rushes, known as borborygmi, are often associated with small bowel obstruction. Occasionally, borborygmi can be auscultated in lactose intolerance cases.[9]

The diaphragm should be placed above the umbilicus to listen for an aortic bruit and then moved 2 cm above and lateral to the umbilicus to listen for a renal bruit. An aortic bruit indicates an abdominal aortic aneurysm and a renal bruit suggests renal artery atherosclerosis.[10] These clinical findings must be correlated with the remaining physical examination and history to formulate a preliminary diagnosis. If delayed gastric emptying is suspected, the examiner should place the stethoscope on the abdomen, hold the patient at the hips, and shake the patient from side to side. If splashing sounds, called the succussion splash, are audible, the test is positive.[11]

Percussion of the abdomen: A proper percussion technique is necessary to gain maximum information regarding abdominal pathology. When percussing, one should appreciate tympany over air-filled structures such as the stomach and dullness to percussion, which may be present due to an underlying mass or organomegaly, such as hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. To detect splenic enlargement, the percussion of the Castell point, the lowest inferior interspace on the left anterior axillary line, can be useful while the patient takes a deep breath. A percussion note that changes from tympanitic to dull as the patient takes a deep breath suggests splenomegaly, with 82% sensitivity and 83% specificity (see Image. Abdominal Radiograph of Splenomegaly). Splenomegaly occurs in trauma with hematoma formation, portal hypertension, hematologic malignancies, infections such as HIV and Ebstein-Barr virus, and splenic infarction.[12]

Percussion is necessary to assess the size of the liver, percussion downward from the lung to the liver, and then the bowel; the examiner may be able to demonstrate the change in percussion notes from resonant to dull and then tympanitic. Shifting dullness, present in ascites, should be demonstrated by percussing from the midline to the flank till the note changes from dull to resonant and then having the patient roll over on their side towards the examiner and wait for 10 seconds. This maneuver allows any fluid, if present, to move downwards. The percussion should then be repeated, moving in the same direction. If the percussion note changes to resonant, shifting dullness is positive.[13][14] With the patient sitting up, the right and left costal-vertebral angles can be percussed to determine renal tenderness, such as pyelonephritis.

Palpation of the abdomen: Preparatory steps before starting the palpation include:

- The patient should be positioned supine, with the head relaxed and the arms on the side of the body. This position is necessary to completely relax the abdominal wall muscles.

- The patient should indicate if they are experiencing any pain in the abdominal area and locate the point of maximal pain.

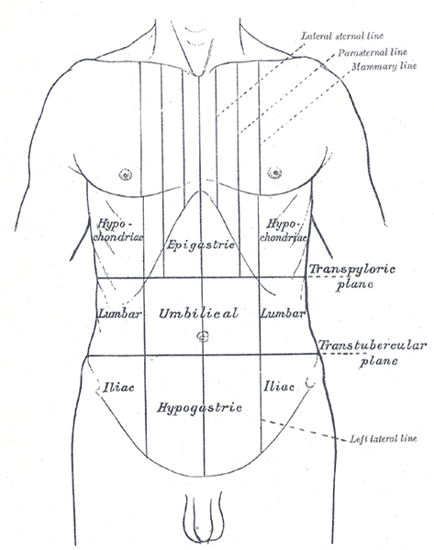

The ideal position for abdominal examination is to sit or kneel on the patient's right side with the hand and forearm in the same horizontal plane as the patient's abdomen. Palpation should be performed in 3 stages in the same order—superficial or light palpation, deep palpation, and organ palpation. Maneuvers specific to certain diseases are also a part of abdominal palpation. The examiner should begin with superficial or light palpation from the area furthest from the point of maximal pain and move systematically through the 9 regions of the abdomen (see Image. Nine Regions of the Abdomen). If no pain is present, any starting point can be chosen. Several sources mention that the abdomen should first gently be examined with the fingertips. Crepitus, a crunching sensation, indicates the presence of air in the subcutaneous tissue.[15] Any irregularity in the abdominal wall should be noted, which may be due to a hernia or a lipoma.

Deep palpation should be performed in the same position of the hand and forearm relative to the patient's abdomen but with firm and steady pressure. Press slowly, as pressing too fast may trap a gas pocket within the intestinal lumen and distend the wall, resulting in false-positive tenderness. During palpation, tenderness should be noted, which may present as guarding. Guarding can be a voluntary process, in which the patient voluntarily tightens the abdominal muscles to protect a deeper inflamed structure, or an involuntary process, where the intra-abdominal pathology has progressed to cause rigidity of the abdominal muscles. Engaging the patient in conversation may help differentiate between voluntary and involuntary guarding, as the former disappears when the patient's attention is diverted. Tenderness in any of the 9 regions of the abdomen may indicate an inflammation of the organs.

Examination of the different areas of the abdomen may indicate separate disease processes. Tenderness of the epigastrium may be due to gastritis or early acute cholecystitis from visceral nerve irritation. Additional findings could include a pulsatile mass from an abdominal aortic aneurysm or abdominal wall defects, such as muscle diastasis. Left lower quadrant tenderness may present a sign of diverticulitis in older people. A mass, if present, could be due to a colon tumor, a left ovarian cyst, or an ectopic pregnancy. In older people, constipation leading to impacted feces may also present with a mass palpated in the left lower quadrant.

In the right lower quadrant, tenderness over McBurney point implies possible appendicitis, inflammation of the ileocolic area that may be due to Crohn disease, or an infection caused by bacteria that have a predilection for the ileocecal area such as Bacillus cereus and Yersinia enterocolitica.

If tenderness is appreciated at McBurney point, the following maneuvers can help identify appendicitis:

- Rovsing sign: When standing on the patient's right side, gradually palpate the left lower quadrant. Increased pain on the right suggests right-sided peritoneal irritation.

- Psoas sign: The examiner should place their hand just above the patient's right knee and ask the patient to push up against your hand. If the appendix is inflamed, this contraction of the psoas muscle causes pain.

- Obturator sign: This sign is performed by flexing the patient's right thigh at the hip with the knee flexed and rotating internally. Increased pain at the right lower quadrant suggests inflammation of the internal obturator muscle from overlying appendicitis or an abscess.[16]

The examiner should palpate the periumbilical area for any defect, mass, or umbilical hernia. The patient can be asked to cough or bear down to feel for any protruding mass. The inguinal and suprapubic areas should not be missed. A detailed examination is recommended if an inguinal or femoral hernia is present. A mass palpated in the suprapubic area may be due to uterine pathology, such as uterine fibroids or uterine cancer in women or bladder mass or distension in both men and women.

The next step is to palpate the abdominal organs. To palpate the liver, the examiner must place the palpating hand below the right lower rib margin and have the patient exhale and then inhale. The liver margin may be felt under the hand with mild pressure as a gentle wave. Noting any nodularity or tenderness is important. To palpate the gallbladder, the examiner should gently place the palpating hand below the right lower rib margin at the midclavicular line and ask the patient to exhale as much as possible. As the patient exhales, the palpating hand should slowly be pushed in deeper, and the patient should then be asked to inhale. The sudden cessation of inspiration due to pain characterizes a positive Murphy sign in acute cholecystitis.[17] To start palpating the spleen, the hand should be placed in the right lower quadrant and moved toward the splenic flexure. When the hand reaches the left lower rib margin, the patient should be asked to exhale and take a deep breath. With mild pressure, the spleen may be felt under the hand as a firm mass if splenomegaly is present. Multiple causes of splenomegaly must be correlated with the patient's history and other physical findings.

A 2-handed technique with the patient in the supine position is used to palpate the kidneys. To palpate the right kidney, the examiner should place the left hand underneath the patient's back, pushing the kidney forward, and the right hand below the right lower rib margin between the midclavicular and anterior axillary lines, gently pushing down. This technique is called balloting. To palpate the left kidney, the examiner should lean onto the patient with the left hand placed around the flank into the patient's loin and place the right hand on the abdomen below the left lower rib margin between the mid-clavicular line and the anterior axillary line. Enlarged or cystic kidneys may be appreciated using this technique.

To estimate the size of the aorta, the patient should be asked to lie supine and completely relax the abdominal wall muscles. A 2-handed technique is preferred, with the left and right hands placed along the lower borders of the left and right costal margins, respectively, and the fingers pointing toward the umbilicus. A generous amount of skin should be left between the 2 index fingers. The aorta can be palpated as a pulsatile mass, and the width can be recorded. A width greater than 2.5 cm indicates an aneurysm and an abdominal ultrasound should be performed for further evaluation. However, an enlarged aneurysm may still not be appreciated by palpation due to body habitus.[18]

Digital Rectal Examination

The abdominal examination ends with the digital rectal examination. After explaining the procedure, obtaining the patient's consent, and ensuring the patient's privacy, the rectal examination should be performed with proper technique. The examiner should place their lubricated, gloved finger against the patient's rectal sphincter muscle to dilate, palpating for hemorrhoids, fissures, or foreign bodies. The prostate for size and firmness should be assessed. Tenderness or bogginess suggests prostatitis, whereas nodules may indicate cancer. After removing the finger, the rectum should be inspected for signs of active bleeding or melena. A Guaiac test should be performed if bleeding is suspected. Examination of the external genitalia should also be performed.

Issues of Concern

The abdominal examination is a crucial part of all comprehensive examinations, whether routine or scheduled, in patients with focused or generalized trauma, those with nonspecific complaints, or specific abdominal or gastrointestinal complaints. However, over the past 2 and a half decades, abdominal examination in the developed world has largely been replaced by imaging techniques. The increased reliance on imaging poses multiple issues. The patient's diagnosis, management, and eventual outcome depend on machine efficiency rather than clinical diagnosis.

An abdominal examination helps diagnose multiple pediatric diseases or conditions. However, performing an abdominal examination in children is challenging particularly due to the difficulty in understanding the procedure and children's lower pain tolerance. Classic findings, such as right lower quadrant tenderness in appendicitis, may not be apparent during abdominal examinations in pediatric patients.[19] Therefore, the abdominal examination should be implemented with relevant diagnostic tests, such as x-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and laboratory evaluation.

Clinical Significance

Abdominal examination is essential to all routine physical examinations and a key step in evaluating abdominal pathology. In emergencies, a brief abdominal examination can help decide further management. Considering the indications for the examination is particularly important in an urgent care clinic, an emergency department, and an intensive care unit where the examination is beneficial to administering enteral nutrition.[20] Based on examination findings, imaging modalities are selected, and appropriate specialist consults are made, which can be crucial for the final diagnosis. These findings are particularly important when communicating with radiologists.[21]

A few recent case studies are highlighted below, emphasizing the value of the abdominal examination in clinical diagnosis:

- A rare case of lupus erythematous panniculitis was identified through abdominal inspection, revealing diffusely scattered ecchymosis with palpable subcutaneous nodules.

- Another rare case involved the perforation of a cecal diverticulum. The abdominal findings included right lower quadrant pain, rebound tenderness, and guarding presumed as appendicitis and treated as such until the pain remained constant, leading to definitive surgical treatment.

- In the pediatric population, abdominal examination is less accurate compared to ultrasound imaging in diagnosing cases of intussusception.[22][23][24]

Accordingly, the clinical significance varies between pediatric and adult populations. Some parts of the abdominal examination are crucial for final diagnosis, whereas others are better diagnosed by laboratory or imaging evaluation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Learning to perform a detailed abdominal examination during graduate school is crucial for aspiring healthcare professionals. This skill is a cornerstone of clinical practice, enabling students to assess patients for a wide range of abdominal conditions accurately. Furthermore, thorough documentation of the examination findings is imperative for determining the diagnostic strategy and management plan. By meticulously recording observations, healthcare providers can establish a comprehensive understanding of the patient's condition. This documentation is a foundation for formulating an effective diagnostic strategy and management plan, guiding subsequent treatment decisions and interventions.

Effective collaboration among healthcare team members is essential for delivering high-quality patient care. Physicians, nurses, and interns must work together to achieve a shared understanding of the patient's condition, which requires open communication, mutual respect, and a willingness to exchange information and insights. By fostering a strong consensus among team members, healthcare providers can ensure that patients receive cohesive, coordinated care that addresses their needs and concerns.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Nine Regions of the Abdomen. The 9 anatomical regions of the abdomen include epigastric, umbilical, hypogastric, and bilateral hypochondriac, lumbar, and iliac regions.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rastogi V, Singh D, Tekiner H, Ye F, Mazza JJ, Yale SH. Abdominal Physical Signs of Inspection and Medical Eponyms. Clinical medicine & research. 2019 Dec:17(3-4):115-126. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2019.1420. Epub 2019 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 31308022]

Rastogi V, Singh D, Tekiner H, Ye F, Mazza JJ, Yale SH. Abdominal Physical Signs and Medical Eponyms: Part I. Percussion, 1871-1900. Clinical medicine & research. 2020 Mar:18(1):42-47. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2018.1428. Epub 2019 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 31324736]

DiLeo Thomas L, Henn MC. Perfecting the Gastrointestinal Physical Exam: Findings and Their Utility and Examination Pearls. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2021 Nov:39(4):689-702. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2021.07.004. Epub 2021 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 34600631]

Ali R, Nagalli S. Hyperammonemia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491436]

Matsuura H, Murata A, Shimazaki T, Sogabe Y. Kayser-Fleischer ring: Wilson's disease. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2017 Aug 1:110(8):531. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcx094. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28472497]

Ayesh MH. Angular cheilitis induced by iron deficiency anemia. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2018 Aug:85(8):581-582. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.85a.17109. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30102595]

Aghedo BO, Kasi A. Virchow Node. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310560]

Sharma B, Raina S. Caput medusae. The Indian journal of medical research. 2015 Apr:141(4):494. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.159322. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26112857]

Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Fox M. Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management. Nutrients. 2015 Sep 18:7(9):8020-35. doi: 10.3390/nu7095380. Epub 2015 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 26393648]

Schoepe R, McQuillan S, Valsan D, Teehan G. Atherosclerotic Renal Artery Stenosis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2017:956():209-213. doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_89. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27873231]

DAVIS NC. INTESTINAL SUCCUSSION SPLASH--A VALUABLE CLINICAL SIGN INSUFFICIENTLY APPRECIATED. The Medical journal of Australia. 1964 Mar 7:1():360-1 [PubMed PMID: 14126366]

Curovic Rotbain E, Lund Hansen D, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell O, Wibrand F, Meldgaard Lund A, Frederiksen H. Splenomegaly - Diagnostic validity, work-up, and underlying causes. PloS one. 2017:12(11):e0186674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186674. Epub 2017 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 29135986]

Schipper HG, Godfried MH. [Physical diagnosis--ascites]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 2001 Feb 10:145(6):260-4 [PubMed PMID: 11236372]

MOSES WR. Shifting dullness in the abdomen. Southern medical journal. 1946 Dec:39(12):985-7 [PubMed PMID: 20274946]

Shieh FK, Dimagno MJ. Abdominal wall pain and crepitus in Marfan's syndrome caused by subcutaneous air. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2008 Feb:6(2):A24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18237859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSnyder MJ, Guthrie M, Cagle S. Acute Appendicitis: Efficient Diagnosis and Management. American family physician. 2018 Jul 1:98(1):25-33 [PubMed PMID: 30215950]

Jeans PL. Murphy's sign. The Medical journal of Australia. 2017 Feb 20:206(3):115-116 [PubMed PMID: 28208037]

Weber MP, Stobart-Gallagher M. Caught on CT! The Case of the Hemodynamically Stable Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Journal of education & teaching in emergency medicine. 2020 Jul:5(3):V14-V17. doi: 10.21980/J8B07B. Epub 2020 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 37465228]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, Perrin EM, Katznelson J, Rice HE. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007 Jul 25:298(4):438-51 [PubMed PMID: 17652298]

Deane AM, Ali Abdelhamid Y, Plummer MP, Fetterplace K, Moore C, Reintam Blaser A. Are Classic Bedside Exam Findings Required to Initiate Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Patients: Emphasis on Bowel Sounds and Abdominal Distension. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2021 Feb:36(1):67-75. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10610. Epub 2020 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 33296117]

Cherla DV, Bernardi K, Blair KJ, Chua SS, Hasapes JP, Kao LS, Ko TC, Matta EJ, Moses ML, Shiralkar KG, Surabhi VR, Tammisetti VS, Viso CP, Liang MK. Importance of the physical exam: double-blind randomized controlled trial of radiologic interpretation of ventral hernias after selective clinical information. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2019 Oct:23(5):987-994. doi: 10.1007/s10029-018-1856-3. Epub 2018 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 30430273]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePacheco ZS, Johnson G, Shufflebarger EF. Female with Atraumatic Abdominal Bruising. Clinical practice and cases in emergency medicine. 2023 Aug:7(3):200-201. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.1247. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37595308]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJabre S, Supino M. An Unusual Case of Right Lower Quadrant Pain: A Case Report. Clinical practice and cases in emergency medicine. 2022 Feb:6(1):61-63. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2021.11.53795. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35226851]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHom J, Kaplan C, Fowler S, Messina C, Chandran L, Kunkov S. Evidence-Based Diagnostic Test Accuracy of History, Physical Examination, and Imaging for Intussusception: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatric emergency care. 2022 Jan 1:38(1):e225-e230. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002224. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32941364]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence