Introduction

While less common than an endodontic abscess, a periodontal abscess is the third most frequent dental emergency requiring immediate intervention due to their rapid onset of pain.[1]

A periodontal abscess is described as a localized accumulation of pus within the gingival wall of a periodontal pocket. More prevalent in patients with previous periodontal pockets,[1] it develops rapidly, destroying periodontal tissues and depicting clear symptoms. If the tooth is associated with multiple abscesses, it may have a “hopeless prognosis.”[2]

Two etiologies explain the development of this entity: periodontitis-related and non-periodontitis-related. Abscesses of periodontitis-related origin usually appear as an exacerbation of the untreated periodontal disease or during periodontal treatment. Abscesses of non-periodontitis-related origin frequently develop due to the impaction of foreign objects, such as a piece of dental floss, or abnormalities of the root anatomy.

The treatment of periodontal abscesses includes drainage, mechanical debridement, and mouth rinses, reserving antibiotic therapy for some cases.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Periodontal abscesses are either directly related to periodontal disease or are independent of it, developing in periodontal pocket-free sites.

Local factors that increase the risk of a periodontal abscess include invaginated tooth, root grooves, cracked tooth, and external root resorption.[3]

Prescribing systemic antimicrobials without mechanical debridement to treat patients with periodontal disease has also been linked to periodontal abscesses.[3] This is believed to be caused by the change in the subgingival bacteria, resulting in a superinfection.[4]

The microbiology of a periodontal abscess is remarkably similar to that of periodontal disease - mainly gram-negative anaerobic bacteria (GNABS). The most prevalent bacteria found in periodontal abscesses are Porphyromonas gingivalis ranging in prevalence from 50 to 100%.[3] Other bacteria implicated in the condition include Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella melaninogenica, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema species, Campylobacter species, Capnocytophaga species, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and gram-negative enteric rods.[5]

Epidemiology

According to a study across general dental practices in the United Kingdom, periodontal abscesses were the third most frequent acute orofacial infection (6 to 7%); behind periapical abscesses (14 to 25%) and pericoronitis (10 to 11%).[6]

Periodontal abscesses have a higher incidence among patients with preexisting periodontal pockets.[1] In a longitudinal study in Nebraska, researchers followed 51 patients with periodontitis over a 7-year time frame, with 27 of these eventually presenting with a periodontal abscess. Twenty-three of the abscesses developed in teeth treated with coronal scaling only, three in teeth that received root planing, and one where the tooth needed treatment with flap surgery. Sixteen out of the twenty-seven abscesses had initial probing depths greater than 6 mm.[7]

Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease have a bi-directional relationship, and that diabetes mellitus can increase the incidence and progression of periodontal disease.[8] There is also evidence that may suggest that patients suffering from diabetes mellitus have a predisposition to developing periodontal abscesses.[9]

Pathophysiology

Most periodontal abscesses originate due to the blockage or obstruction of a periodontal pocket. This may occur due to various reasons, including calculus accumulation, dislodged calculus during debridement pushed into the soft tissues, or a foreign body impaction like dental floss or a piece of toothpick.[3] The periodontal pocket closure impedes the clearance of gingival crevicular fluid, causing an accumulation of bacteria. However, most of the tissue damage in periodontal abscesses is due to the release of lysosomal enzymes from host neutrophils.[5]

Histopathology

De Witt et al. studied biopsy samples of periodontal abscesses.[10] From the exterior to the interior, they found:

- Normal oral epithelium and lamina propia

- Acute inflammatory infiltrate

- A focus of neutrophil-lymphocyte inflammation, with an encompassing connective tissue that was necrotic and destroyed

- An ulcerated pocket epithelium

- A central area of granular acidophilic and amorphous debris

History and Physical

It is essential to inquire if the patient has a history of periodontal treatment, including any current debridement or antimicrobials. Evidence suggests that contributing factors include residual calculus, introducing bacteria into the gingival pockets during debridement, and bacterial superinfection due to antibiotic treatment.[11]

Periodontal abscesses secondary to foreign body impaction are identifiable through a history taking from the patient.

While taking the patient's medical history, extra emphasis should focus on diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes mellitus due to the increased predisposition to developing periodontal abscesses in these patients.[12]

The most prevalent presenting complaint is an intra-oral swelling with or without pain.[13] Patients may report pain exacerbated by biting, and due to the loss of the periodontal structure, the tooth can feel loose. A sensation of tooth elevation is also commonly reported. A purulent exudate is seen mainly on pressure or probing, and patients report a bad taste associated with pus.

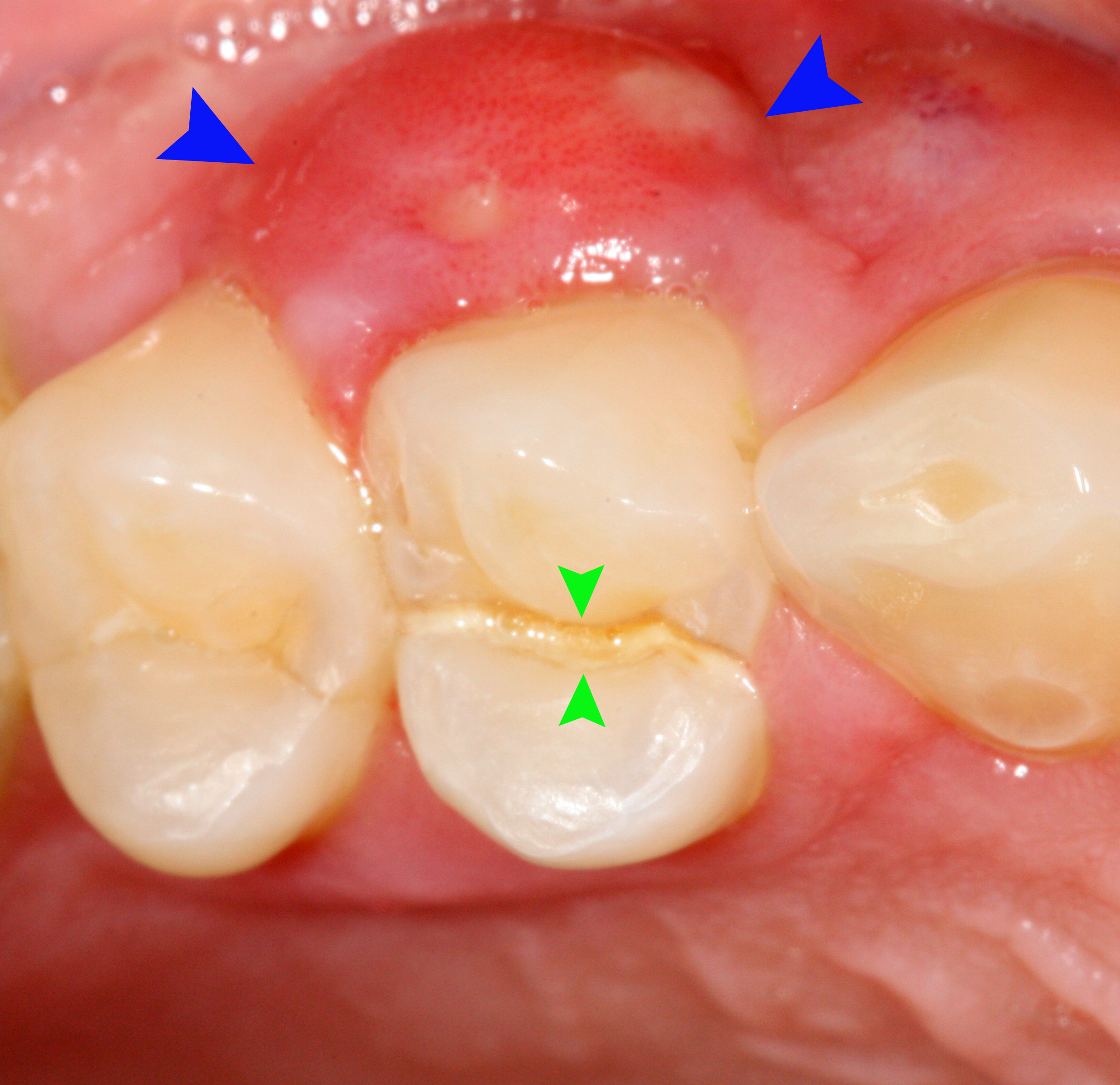

Clinical examination is paramount in aiding the diagnosis. Typically, signs include those of periodontal diseases: increased probing depths (usually greater than 6 mm), suppuration, tooth mobility, and furcation involvement. Other findings include tenderness to palpation and lateral percussion. Looking at the lateral portion of the root, clinicians may notice an ovoid elevation of the gingivae [5], but abscesses situated deep in the periodontium are less noticeable. The tooth will typically respond well to electric or thermal pulp testing since the cause is periodontal, not endodontic.

Classification

Periodontal abscesses are classified depending on the location, duration of the infection, and their number. According to the location, they are divided into gingival and periodontal; gingival abscesses are restricted to the gingival margin and interdental papillae, caused mainly by an object impaction [1]. Periodontal abscesses affect deeper periodontal structures, such as deep pockets and bone defects, usually linked to periodontal disease.

According to the duration of the infection, they are classified into chronic and acute, featuring different symptoms. An acute periodontal abscess’s symptoms include pain, tenderness on palpation, and the presence of pus. In contrast, a chronic abscess is more associated with a sinus tract and mild or absent pain [1].

According to the number, they are divided into single, usually caused by a local obstruction, and multiple abscesses: associated with systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, and patients taking antibiotic treatment for non-oral issues with untreated, periodontal disease.

Evaluation

Periapical radiographs are critical in evaluating the periodontal hard tissues. Widening of the periodontal ligaments and horizontal or vertical bone loss is often expected.

A periapical radiolucency is usually an indication of an endodontic abscess or a combination of a periodontal and endodontic abscess. The latter often demonstrates characteristic alveolar bone loss extending to the periapical lesions.

A practical way to determine the source of the infection is inserting a gutta-percha point along the sinus tract or into the periodontal pocket and identifying the point of termination with a periapical radiograph.[12]

In some particular cases, darkfield microscopic examination of the abscess is used to rule out a periapical abscess due to the difference in the microflora. Positron emission tomography has high accuracy in detecting periodontal and other anaerobic abscesses in the oral cavity.[1]

Treatment / Management

Treatment predominantly consists of two phases: acute management and definitive treatment once the acute phase has been resolved. Acute treatment aims to alleviate the symptoms and reduce the risk of the spread of infection.[14] The abscess must be drained ideally by careful root surface debridement via the periodontal pocket or by incising over the area of greatest fluctuant swelling on the gingiva. Local anesthesia may be required. Drainage should be accompanied by the mechanical scaling of the periodontal pocket and antiseptic rinse, removing necrotic tissue and bacterial load. This enables the host immune response to tackle the infection.

Postoperatively, warm salt water rinses are encouraged, and copious fluid intake to reduce the swelling. Dental practitioners must reassess the lesion and develop a long-term treatment plan as necessary, usually consisting of periodontal therapy.[15](B3)

Exodontia is indicated when the clinician deems tooth prognosis poor or hopeless, whether from periodontal disease or the destruction caused by the abscess.[3]

If the cause of the abscess is an embedded foreign object, this must be removed through debridement, and drainage through the gingival sulcus should be performed either with a periodontal probe or by smooth scaling. Finally, a warm saline rinse is indicated. Follow up after one to two days.[1]

Antimicrobial therapy is only recommended as an adjunct to mechanical treatment in patients with a compromised immune system or with systemic spread.[16] Systemic involvement presents as fever, fatigue, cellulitis, or lymphadenopathy. When selecting an antibiotic, the professional should consider susceptibility and resistance of the bacterial strain, patient allergies, and drug interactions. Amoxicillin, combined with clavulanic acid, is the first choice of antibiotic. Clindamycin is recommended as an alternative for patients with penicillin allergies.[14]

Patients with multiple periodontal abscesses should be referred for further assessment due to the likelihood of an underlying systemic condition, such as diabetes mellitus.

Periodontal surgery, including gingivectomy or flap procedures, can be used in cases of chronic periodontal abscesses.[1] These surgical procedures aim to remove the residual calculus and drain the abscess. They are especially useful in abscesses related to deep vertical defects. Periodontal flaps have been suggested in periodontal abscesses that develop after periodontal therapy, where the calculus is left subgingivally.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

Thorough anamnesis and clinical findings are crucial in distinguishing between other oral pathologies.[17]

Periapical abscess: a history of trauma, tooth wear, fracture, caries, or deep restoration may indicate pulpal damage. Vitality testing with electric or thermal stimulation will either provide a negative or inconclusive response. Radiographically, a periapical radiolucency may be evident if the patient is experiencing an acute exacerbation of a chronic periapical lesion.

Combined periodontic-endodontic abscesses: can be categorized according to the origin of the infection into primary endodontic abscess with secondary periodontal involvement, primary periodontal abscess with secondary endodontic involvement, or a true combined periodontal-endodontic abscess. Correct diagnosis relies on collaborating the history, clinical examination, and pulp testing, and intraoral radiographs.[18] Positive pulp testing suggests periodontal origin, whereas a lack of response suggests endodontic origin.

Pericoronal abscess: abscesses from a partially erupted tooth can often mimic a periodontal abscess. Clinicians should look out for vital adjacent teeth with no increased periodontal pocketing.[3]

Partial root fracture: fractures are detectable through visual inspection, increased mobility, and tenderness. Taking radiographs from different angles can help to detect fractures. Similarly, endodontic perforations or perforations resulting from posts are also detectable through intraoral radiographs of alternative angulations.[3]

Squamous cell carcinoma: clinicians should be vigilant when assessing and treating recurrent periodontal abscesses as literature reveals cases of gingival squamous cell carcinomas mimicking periodontal disease and their associated abscesses.[19]

Self-inflicted gingival injuries: habits such as nail-biting and trauma due to objects, e.g., pens and pins, can cause similar-looking lesions. These can be ruled out through taking a complete history, and there should be considerations regarding habit dissuasion methods.

Other less common differentials include lateral periapical cyst, postoperative infection, odontogenic myxoma, metastatic carcinoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, pyogenic granuloma, osteomyelitis, odontogenic keratocyst, eosinophilic granuloma, and post-surgical abscess.[3]

Prognosis

Periodontal abscesses characteristically demonstrate the rapid destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. They can significantly influence the prognosis of a tooth and may lead to tooth loss; this is particularly true for patients who already have moderate to severe attachment loss.

A retrospective study on the frequency of tooth loss due to periodontal abscess found that 45% of teeth with a periodontal abscess were extracted during supportive therapy.[20] Just above a half were successfully maintained for 12.5 years on average, and teeth with furcation involvement were most likely to be extracted compared to non-furcated teeth.[20]

Furthermore, teeth with repeated abscess formation have a very poor prognosis.[2]

The evidence suggests that there are poorer outcomes for teeth with existing periodontal disease. Due to the rapid destructive nature of the disease, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to improving the prognosis.[21]

Complications

If left untreated, the dental abscess can cause further breakdown of the periodontal structure, decreasing the tooth's long-term prognosis - particularly relevant for patients exhibiting moderate to severe periodontal disease.[3] Teeth with periodontal abscesses may require extraction in the future due to recurrent abscesses, pain, or increased mobility.[20] Untreated, periodontal abscesses may result in the systemic spread of infection; they can progress to extra-oral head and neck swellings, lymphadenopathy, and even sepsis.[3]

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is essential to educate patients on the main contributing risk factors to tackle the periodontal abscess causes:

- Oral hygiene: brushing twice a day along the gingival margins and using interdental aids helps to reduce plaque accumulation and bacterial load.

- Diabetes mellitus: educating patients on the bi-directional relationship between periodontitis and diabetes helps promote the importance of better diabetic control. Liaising with general medical practitioners can be beneficial in addressing this situation.

- Smoking: offering smoking cessation advice can help reduce the patient’s risk of periodontitis, oral cancer, and general well-being.Family history: although an unmodifiable risk, awareness of susceptibility can motivate patients to maintain good oral hygiene and seek care earlier and more frequently.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach can help improve patient outcomes; this may involve referral to a hygienist or periodontal specialist for regular therapy or surgery for periodontal disease. It is essential for general medical practitioners and clinicians in the emergency department to recognize both signs and systems of periodontal abscesses and underlying contributing factors that may need addressing. [Level 4]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Herrera D, Roldán S, Sanz M. The periodontal abscess: a review. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2000 Jun:27(6):377-86 [PubMed PMID: 10883866]

Becker W, Berg L, Becker BE. The long term evaluation of periodontal treatment and maintenance in 95 patients. The International journal of periodontics & restorative dentistry. 1984:4(2):54-71 [PubMed PMID: 6589217]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHerrera D, Alonso B, de Arriba L, Santa Cruz I, Serrano C, Sanz M. Acute periodontal lesions. Periodontology 2000. 2014 Jun:65(1):149-77. doi: 10.1111/prd.12022. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24738591]

Helovuo H, Hakkarainen K, Paunio K. Changes in the prevalence of subgingival enteric rods, staphylococci and yeasts after treatment with penicillin and erythromycin. Oral microbiology and immunology. 1993 Apr:8(2):75-9 [PubMed PMID: 8355988]

Herrera D, Retamal-Valdes B, Alonso B, Feres M. Acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses and necrotizing periodontal diseases) and endo-periodontal lesions. Journal of periodontology. 2018 Jun:89 Suppl 1():S85-S102. doi: 10.1002/JPER.16-0642. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29926942]

Lewis MA, Meechan C, MacFarlane TW, Lamey PJ, Kay E. Presentation and antimicrobial treatment of acute orofacial infections in general dental practice. British dental journal. 1989 Jan 21:166(2):41-5 [PubMed PMID: 2917089]

Kaldahl WB, Kalkwarf KL, Patil KD, Molvar MP, Dyer JK. Long-term evaluation of periodontal therapy: I. Response to 4 therapeutic modalities. Journal of periodontology. 1996 Feb:67(2):93-102 [PubMed PMID: 8667142]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNascimento GG, Leite FRM, Vestergaard P, Scheutz F, López R. Does diabetes increase the risk of periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of longitudinal prospective studies. Acta diabetologica. 2018 Jul:55(7):653-667. doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-1120-4. Epub 2018 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 29502214]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMeng HX. Periodontal abscess. Annals of periodontology. 1999 Dec:4(1):79-83 [PubMed PMID: 10863378]

DeWitt GV, Cobb CM, Killoy WJ. The acute periodontal abscess: microbial penetration of the soft tissue wall. The International journal of periodontics & restorative dentistry. 1985:5(1):38-51 [PubMed PMID: 3888899]

Herrera D, Roldán S, González I, Sanz M. The periodontal abscess (I). Clinical and microbiological findings. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2000 Jun:27(6):387-94 [PubMed PMID: 10883867]

Corbet EF. Diagnosis of acute periodontal lesions. Periodontology 2000. 2004:34():204-16 [PubMed PMID: 14717863]

Smith RG, Davies RM. Acute lateral periodontal abscesses. British dental journal. 1986 Sep 6:161(5):176-8 [PubMed PMID: 3465335]

López-Píriz R, Aguilar L, Giménez MJ. Management of odontogenic infection of pulpal and periodontal origin. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2007 Mar 1:12(2):E154-9 [PubMed PMID: 17322806]

Knevel RJ, Kuijkens A. Is your knowledge up-to-date? International journal of dental hygiene. 2003 Nov:1(4):238-40 [PubMed PMID: 16451508]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSeppänen L,Lauhio A,Lindqvist C,Suuronen R,Rautemaa R, Analysis of systemic and local odontogenic infection complications requiring hospital care. The Journal of infection. 2008 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 18649947]

Marquez IC. How do I manage a patient with periodontal abscess? Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 2013:79():d8 [PubMed PMID: 23522148]

Singh P. Endo-perio dilemma: a brief review. Dental research journal. 2011 Winter:8(1):39-47 [PubMed PMID: 22132014]

Gupta R, Debnath N, Nayak PA, Khandelwal V. Gingival squamous cell carcinoma presenting as periodontal lesion in the mandibular posterior region. BMJ case reports. 2014 Aug 19:2014():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202511. Epub 2014 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 25139914]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcLeod DE, Lainson PA, Spivey JD. Tooth loss due to periodontal abscess: a retrospective study. Journal of periodontology. 1997 Oct:68(10):963-6 [PubMed PMID: 9358362]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSilva GL, Soares RV, Zenóbio EG. Periodontal abscess during supportive periodontal therapy: a review of the literature. The journal of contemporary dental practice. 2008 Sep 1:9(6):82-91 [PubMed PMID: 18784863]