Introduction

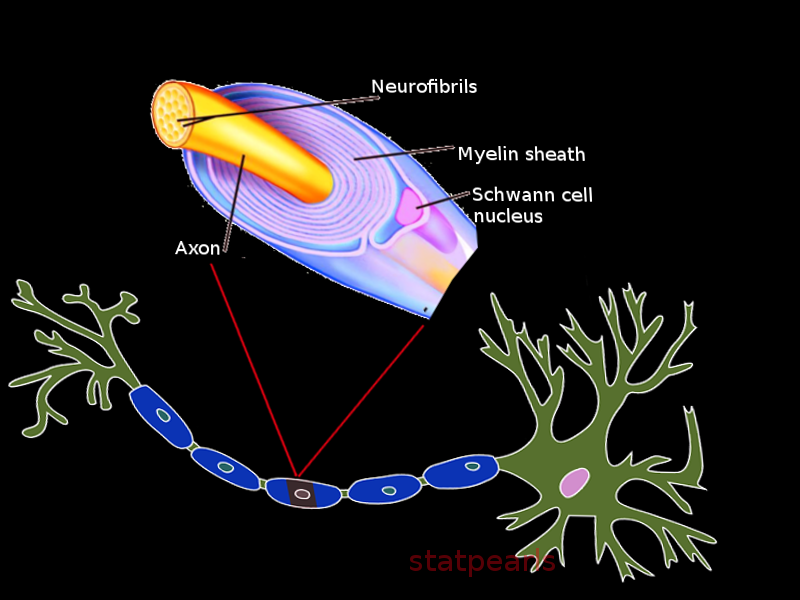

Myelin sheath is a fatty product formed from specific neuroglial cells that provides numerous vital supporting functions as well as increases the rate of conduction of action potentials for some central and peripheral nervous system neurons. An axon wrapped in myelin sheath is said to be myelinated fibers, as such, axons not wrapped in myelin are non-myelinated fibers. In the central nervous system, the myelinated fibers have the collective name of white matter, and the nonmyelinated fibers are collectively known as gray matter as they look white and gray respectively on gross inspection of the brain in sagittal cross-section. Myelin is formed via oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells in the central and peripheral nervous systems respectively. Many physiologic complications and clinical symptoms can arise from the malformation and destruction of myelin.

Structure

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure

Myelin is known for having several structural features, most notably, the nodes of Ranvier and myelin incisures (Schmidt-Lantermann clefts). The nodes of Ranvier are the region where two adjacent myelin segments meet and allow for saltatory conduction to occur. Myelin incisures are pouches of Schwann cell cytoplasm, left over from the myelination process, and are believed to play a major role in Wallerian degeneration.[1][2][3]

Function

In both peripheral and central nervous systems, myelin plays a crucial role in the protection and conduction of many neurons. Myelin sheath acts as an insulator allowing for protection of the integrity of the nerve impulse as well as protecting the axon from foreign electrical impulses. Myelin also yields the formation of the nodes of Ranvier which allow for saltatory conduction and faster propagation of action potentials to occur.[4]

Tissue Preparation

Historically, an aldehyde fixation was used to fix the nervous tissue for use in electron microscopy. Today, histological fixing of the nervous tissue is commonly done via a high-pressure freezing technique which yields a better-contrasted specimen as well as better preservation of the nervous tissue with fewer artifacts due to better fixation. However, aldehydes, such as formalin, are still used as a fixation solution for purposes of light microscopy as the decreased contrast, and inferior preservation of the tissue is negligible for use in routine nervous tissue studies.[5][6]

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

In the central nervous system, myelin can undergo assessment via the use of anti-proteolipid protein and anti-myelin basic protein immunohistochemical stains; this is because both the myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein are present in oligodendrocytes as well as myelin sheath in the central nervous system.[7]

Microscopy, Light

Myelin can be seen using light microscopy using various histological methods, such as but not limited to: hematoxylin and eosin, Luxol fast blue and plastic (paraffin) embedding. These histological methods pronounce myelin and typically makes it appear as peripheral rings surrounding an axon when looking at a transverse section and as long parallel projections when viewing a longitudinal section. The nuclei of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells are visible on hematoxylin & eosin staining; this presents as circular basophilic nuclei with a perinuclear halo giving a “fried-egg” appearance and as longitudinal basophilic nuclei proximal to an axon respectively. Light microscopy is one of the most commonly used methods used to assess the presence of specific pathology in nervous tissue.[8][9]

Microscopy, Electron

Myelin can be seen on transmission electron microscopy typically as a thick dark outline surrounding myelinated nerve fibers. In research, the use of three-dimensional electron microscopy can be used to view various injuries and disease processes related to the myelin sheath. This technique is typically not used clinically but has prospects to be advantageous to further the understanding of various pathophysiologic processes.[5][10]

Pathophysiology

Myelin sheath formation initiates in the CNS of the human embryo at about four months gestation. Oligodendrocytes can myelinate multiple axons at the same time (up to 50), and as such, any given myelinated neuron in the central nervous system can undergo myelination by several oligodendrocytes. Myelination of neurons in the peripheral nervous system commences between the twelfth and eighteenth week of gestation. Unlike oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells surround only a single axon. Schwann cells also play a role in peripheral neuron regeneration after an injury.

Disruptions of myelin sheath formation and/or autoimmune-related destruction of myelin sheath can often lead to serious neurological complications. These disruptions are commonly referred to as demyelinating diseases. The most common demyelinating disease is multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disorder with the patients' own antibodies directing their efforts against the myelin sheath in their central nervous system. Multiple sclerosis has a prevalence of about one in every thousand persons in the United States with women being affected with the disease two times as much as men. Histologically, multiple sclerosis shows abrupt edges of demyelinated plaque when stained with specific myelin stains. More specifically, light microscopy can view active plaques, in which there is active and progressive demyelination with PAS-stain positive breakdown product and lipid-rich macrophages present, as well as inactive plaques, in which there is no active demyelination taking place, and thus no myelin or myelin degradation products are found. That said, in inactive plaques, there is a reduction of oligodendrocytes nuclei, and there’s an increase in astrocytic proliferation. The third type of plaques seen in multiple sclerosis patients demonstrates non-abrupt borders between the normal and demyelinated tissue. These “shadow plaques” are theorized to be due to oligodendrocytes that did not get destroyed and that partially re-myelinate the damaged tissue.

Multiple sclerosis typically presents clinically with visual disturbances such as diplopia and monocular blindness as well as peripheral symptoms of muscle weakness, sensory deficits, and subsequently ataxia.

The cause of multiple sclerosis remains unknown. However, there has been a higher prevalence of multiple sclerosis in regions more north of the equator than those close or south of the equator; this leads many researchers to believe there’s a genetic and environmental component. Guillain-Barre syndrome is another demyelinating disorder, but unlike multiple sclerosis, there is autoimmune destruction of the myelin sheath in the peripheral nervous system as opposed to the central nervous system.

Guillain-Barre is rarer than multiple sclerosis, only affecting one in every one hundred thousand persons every year and affects males and females equally.[11][12][13] Guillain-Barre syndrome typically presents as an ascending paralysis and muscle weakness, with it’s most severe and life-threatening complication being respiratory depression. The cause of Guillain-Barre disease is also not yet known, but triggers include microbial infection, traumatic surgery, or, very rarely, vaccination.[14][15][16]

Clinical Significance

Demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Guillain-Barre syndrome have a progressive and devastating effect on affected patients. There has not been an approved treatment to reverse the demyelinating process in these diseases. However, there is an array of medications that can be used to slow the progression and to treat the symptoms that may arise from them. That said, these medications are not without potential shortfalls and side-effects. For example, beta interferons are commonly prescribed to the patients to help slow the progression of disease in multiple sclerosis. However, the use of beta interferons have been shown to induce flu-like symptoms as well as liver damage, but it is still widely used in many patients due to the therapeutic effects of the drug outweighing its potential adverse side-effects.[17][18]

Media

References

Salzer JL. Clustering sodium channels at the node of Ranvier: close encounters of the axon-glia kind. Neuron. 1997 Jun:18(6):843-6 [PubMed PMID: 9208851]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmall JR, Ghabriel MN, Allt G. The development of Schmidt-Lanterman incisures: an electron microscope study. Journal of anatomy. 1987 Feb:150():277-86 [PubMed PMID: 3654340]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhabriel MN, Allt G. The role of Schmidt-Lanterman incisures in Wallerian degeneration. I. A quantitative teased fibre study. Acta neuropathologica. 1979 Nov:48(2):93-93 [PubMed PMID: 506700]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNave KA, Werner HB. Myelination of the nervous system: mechanisms and functions. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2014:30():503-33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013101. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25288117]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMöbius W, Nave KA, Werner HB. Electron microscopy of myelin: Structure preservation by high-pressure freezing. Brain research. 2016 Jun 15:1641(Pt A):92-100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.02.027. Epub 2016 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 26920467]

Fix AS, Garman RH. Practical aspects of neuropathology: a technical guide for working with the nervous system. Toxicologic pathology. 2000 Jan-Feb:28(1):122-31 [PubMed PMID: 10668998]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMithen FA, Wood PM, Agrawal HC, Bunge RP. Immunohistochemical study of myelin sheaths formed by oligodendrocytes interacting with dissociated dorsal root ganglion neurons in culture. Brain research. 1983 Feb 28:262(1):63-9 [PubMed PMID: 6187412]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiko TL, Gschmeissner SE. Histological methods for assessing myelin sheaths and axons in human nerve trunks. Biotechnic & histochemistry : official publication of the Biological Stain Commission. 1994 Mar:69(2):68-77 [PubMed PMID: 8204769]

Daumas-Duport C, Scheithauer BW, Kelly PJ. A histologic and cytologic method for the spatial definition of gliomas. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1987 Jun:62(6):435-49 [PubMed PMID: 2437411]

Giacci MK, Bartlett CA, Huynh M, Kilburn MR, Dunlop SA, Fitzgerald M. Three dimensional electron microscopy reveals changing axonal and myelin morphology along normal and partially injured optic nerves. Scientific reports. 2018 Mar 5:8(1):3979. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22361-2. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29507421]

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet (London, England). 2008 Oct 25:372(9648):1502-17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18970977]

Anderson DW, Ellenberg JH, Leventhal CM, Reingold SC, Rodriguez M, Silberberg DH. Revised estimate of the prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Annals of neurology. 1992 Mar:31(3):333-6 [PubMed PMID: 1637140]

. Fact sheet on Guillain-Barré syndrome (updated October 2016. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire. 2017 Feb 3:92(5):50-2 [PubMed PMID: 28155266]

Sharpe RJ. The low incidence of multiple sclerosis in areas near the equator may be due to ultraviolet light induced suppressor cells to melanocyte antigens. Medical hypotheses. 1986 Apr:19(4):319-23 [PubMed PMID: 2940440]

Levitt P, Veenstra-VanderWeele J. Neurodevelopment and the origins of brain disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015 Jan:40(1):1-3. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.237. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25482168]

Barateiro A, Brites D, Fernandes A. Oligodendrocyte Development and Myelination in Neurodevelopment: Molecular Mechanisms in Health and Disease. Current pharmaceutical design. 2016:22(6):656-79 [PubMed PMID: 26635271]

Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, Herndon RM, Richert JR, Salazar AM, Fischer JS, Goodkin DE, Granger CV, Simon JH, Alam JJ, Bartoszak DM, Bourdette DN, Braiman J, Brownscheidle CM, Coats ME, Cohan SL, Dougherty DS, Kinkel RP, Mass MK, Munschauer FE 3rd, Priore RL, Pullicino PM, Scherokman BJ, Whitham RH. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Annals of neurology. 1996 Mar:39(3):285-94 [PubMed PMID: 8602746]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVerboon C, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Treatment dilemmas in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2017 Apr:88(4):346-352. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314862. Epub 2016 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 27837102]