Introduction

Thermal burns are skin injuries caused by excessive heat, typically from contact with hot surfaces, hot liquids, steam, or flame. Most burns are minor and can be treated as outpatients or at local hospitals. Approximately 6.5% of all burned patients receive treatment in specialized burn centers. The decision to transfer and treat at burn centers is based on the extent of body surface area burned, the depth of the burns, and individual patient characteristics such as age, other injuries, or other medical problems.[1][2][3][4]

Burns occurring in the home account for 25% of all serious burns.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Thermal burns are the most common type of burn injuries, making up about 86% of the burned patients requiring burn center admission. Burns often result from hot liquids, steam, flame or flash, and electrical injury. Risk factors for thermal burns include:

- Young age - children often come into contact with hot liquids

- Male gender - males are also at high risk for burn injuries chiefly due to occupation-related injuries. Additionally, flame burns are also common during the summer, as many people use gasoline products for recreation or farming. Alcohol consumption is a common risk factor in adults who suffer burn injuries.

- Lack of smoke detectors in the home

When immersion scald burns are present, one should always suspect child abuse by the parent or caretaker.

Epidemiology

Approximately 450,000 patients received treatment for burns annually, and about 30,000 require admission to burn centers. About 86% of burns are thermal burns (43% from fire/flame, 34% from scalds, 9% from hot objects), 4% electrical burns, 3% chemical burns, and 7% are other types of burns. Annually, approximately 3400 patients die from burns or related complications such as smoke inhalation, carbon monoxide or cyanide poisoning, organ failure, or infection. Roughly 72% of these deaths occur from residential fires. Burns represent the fourth leading cause of trauma deaths and the second leading cause of accidental deaths in children ages one to four. The good news is that the overall survival rate for all types of burns is about 97%, and deaths from burns have declined by about 75% from the 1960s.

Pathophysiology

The skin is the largest organ of the body, making up about 16% of a person’s weight. The main skin functions are protection (infection, temperature changes, physical forces, chemicals, etc.), body temperature regulation, preventing fluid loss, and cosmetic/identity. Two primary layers comprise the skin, the thinner outer layer called the epidermis, and the deeper, thicker layer called the dermis. There are various other structures within the skin like hair follicles, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, capillaries, and nerve endings.

Thermal burns cause both local injuries and, if severe (> 20% of body surface area), a systemic response. The local injuries can be roughly separated into three zones of injury analogous to a circular target pattern. The innermost injury is the zone of coagulation or necrosis, representing the area of irreversible cell death. Surrounding this is the zone of ischemia or stasis, representing an area of decreased circulation and an area at increased risk of progression to necrosis due to hypoperfusion or infection. The outermost area is the zone of hyperemia, representing an area of reversible vasodilation and an area that usually returns to normal. In clinical practice, burns are dynamic injuries that may progress over hours to days, making it difficult to accurately determine the various zones during the early course of the injury.

Large burns (>20% body surface area) also cause a systemic response from the release of inflammatory and vasoactive mediators. Fluid loss locally at the burn site, fluid shifts systemically, plus decreased cardiac output and increased vascular resistance, can all lead to marked hypovolemia and hypoperfusion called “burn shock.” This condition can be managed with aggressive fluid resuscitation, as discussed in the Burn, Resuscitation, and Management chapter.

History and Physical

Most burns are small and classify as minor burns with the primary symptom being pain. These burns will need only local burn wound care and pain control. If the patient has extensive and deep burns, then they may be classified as severe burns and could be approached like other trauma patients (See Burns, Resuscitation, and Management for discussion of severe burns). If the patient does not have severe burns, then the history and physical examination can proceed as usual. Key parts of the history to include are the type of burn (thermal, electrical, chemical, radiation), the possibility of associated inhalation injury (e.g., trapped in an enclosed space), and the possibility of other injuries (e.g., explosion or jumped to escape fire).[5][6][7][8]

During the physical exam, special attention should be placed on the airway and breathing, looking for oral burns, facial burns, soot in the nose or mouth, coughing, wheezing, or labored breathing. Also, look for signs of injury other than the burns. Finally, the burns are the focus of the skin exam. The key features to assess are the extent of the burns, expressed as a percent of total body surface area burned (% TBSA), and the depth of the burns, expressed as superficial (or first-degree), partial-thickness (or second-degree), or full-thickness (or third-degree).

If the burn injury only involves the epidermis, it is classified as a superficial or first-degree burn and does not cause any significant impairment of normal skin function. If the injury extends into the dermis, it classifies as partial-thickness or second-degree burn. Partial-thickness burns may disrupt skin functions such as protection from infection, thermal regulation, prevention of fluid loss, and sensation. If the injury extends through both layers, this is a full-thickness or third-degree burn, and normal skin functions are lost.

Superficial (or first-degree) burns are warm, painful, red, soft, usually do not blister, and will blanch when touched. A typical example is a sunburn. Partial-thickness (or second-degree) burns can vary but are very painful, red, blistered, moist, soft, and will blanch when touched. Examples include burns from hot surfaces, hot liquids, or flames. Full-thickness (or third-degree) burns have little or no pain, can be white, brown, or charred and feel firm and leathery when touched and will not blanch. Examples include burns from flames, hot oils, or superheated steam.

Evaluation

The American Burn Association's criteria can help differentiate burns as minor, moderate, or severe based on the extent of skin injured, the depth of the burns, age of the patient (<10 or >50 y/o), associated medical conditions, associated injuries such as smoke inhalation or other trauma, or burns involving particular areas of the body such as the hands, feet, face, ears, nose, or genitalia (See also Burns, Evaluation and Management for more details regarding determining depth and extent of burns).[9][10][11][12]

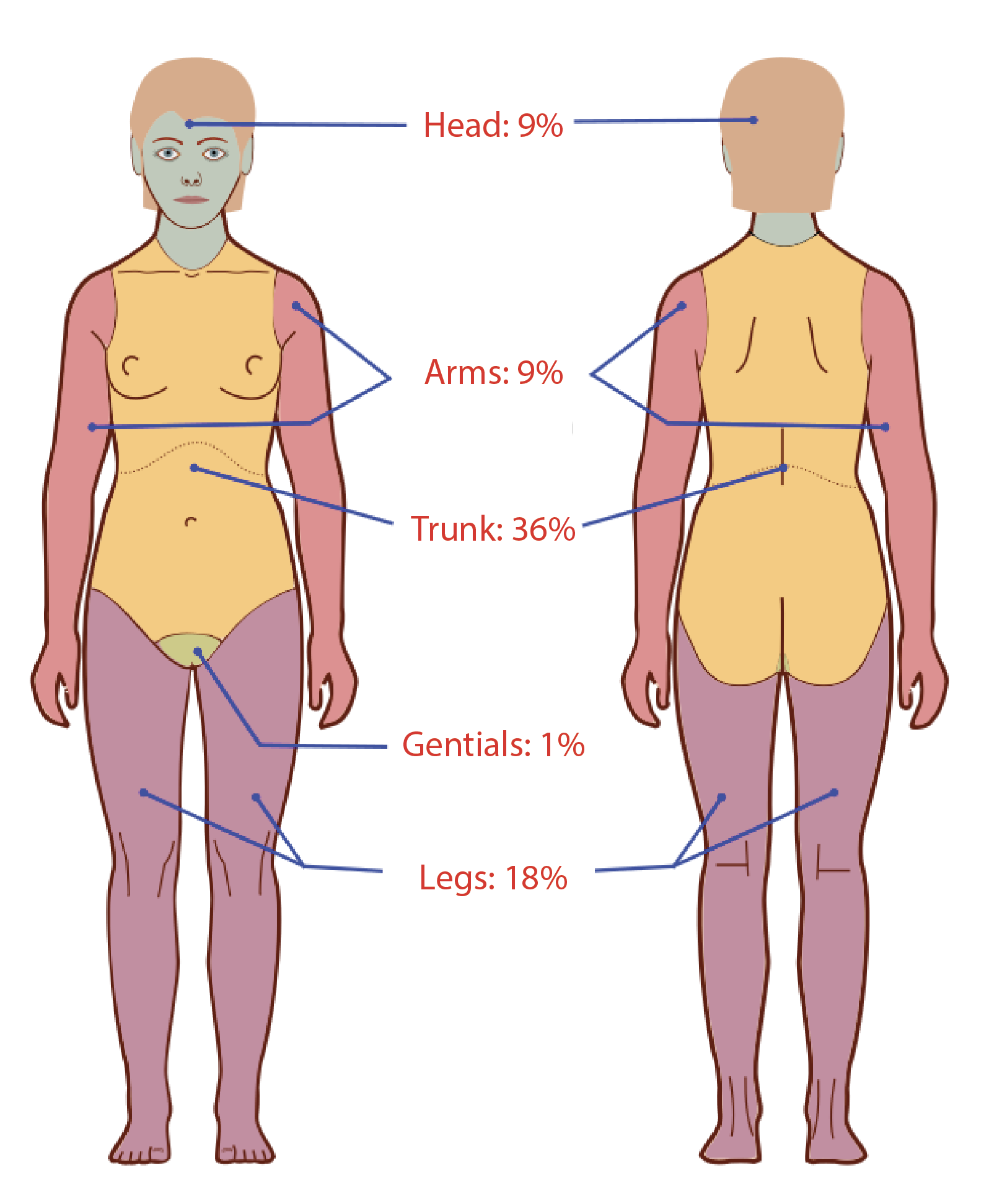

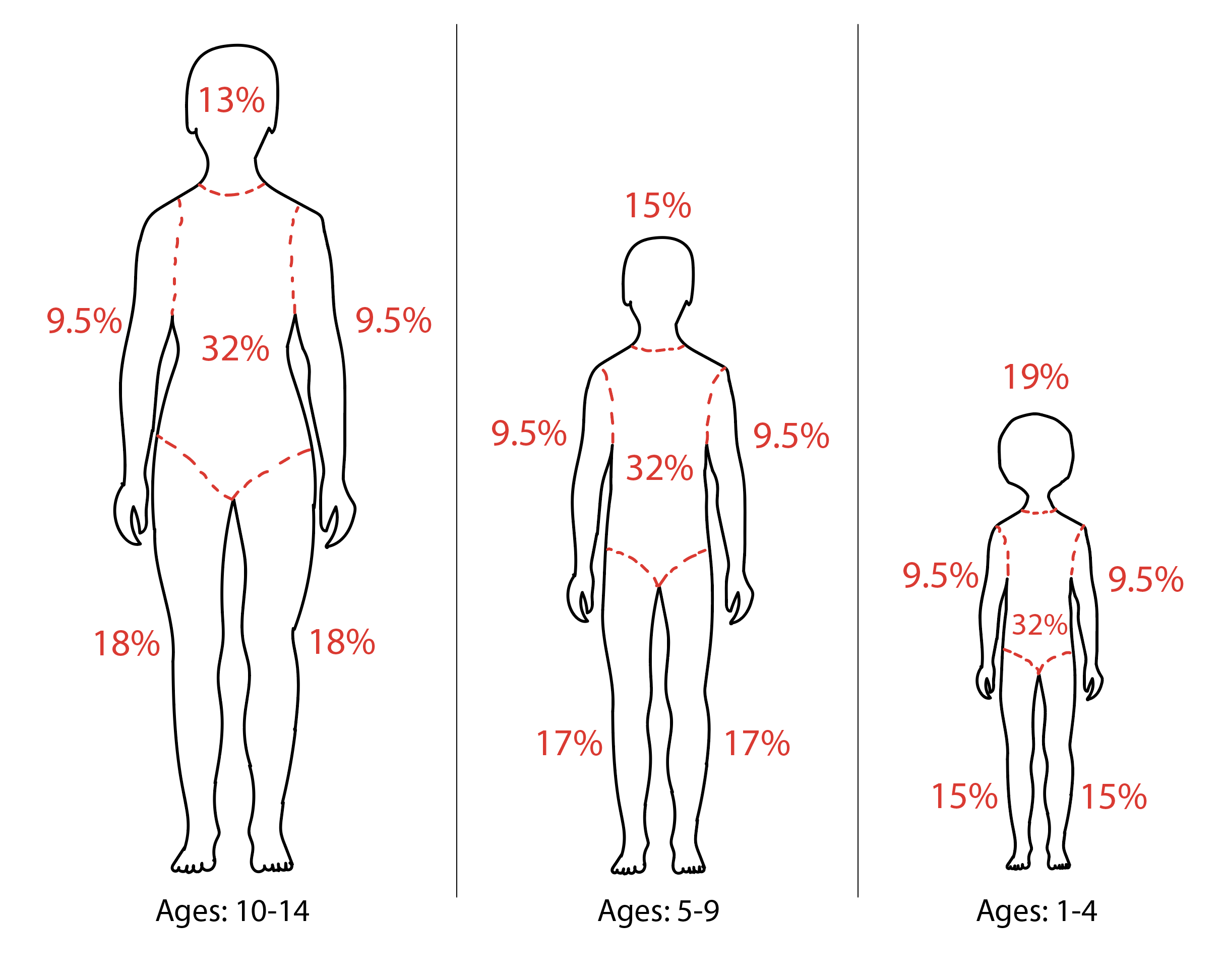

Burn size quantification is essential when making decisions about treatment and admission, and the rule of nines is often used.

For adults:

- 9% of the total body surface area to the head and neck

- 9% to each upper extremity

- 18% to the anterior and posterior trunk

- 18% to each lower extremity

- 1% to the perineum

The patient's palm represents about 1% of the total body surface area. Also, burn injury can subdivide into partial and full-thickness injury.

Major Burn Injury

- More than 25% of total body surface area in adults or 20% in children

- Full-thickness burn involving more than 10% of TBSA

- There is burn to the face, perineum, or extremities

- There is significant cosmetic impairment

- These injuries are best managed in a burn center

Moderate Burn Injury

- Partial-thickness burn between 15 to 20% TBSA in adults, 10 to 15% in children or a full-thickness burn involving 2 to 10% TBSA

- Minimal threat to face and perineum

- The risk of cosmetic impairment is not severe

- These patients need admission but do not always require a referral to a burn center.

Minor Burn Injury

- Burns that involves less than 15% of TBSA in adults and less than 10% in children

- No threat of functional or cosmetic loss

- Face and perineum not involved

- These burns receive outpatient management.

Treatment / Management

Burn treatment begins at the site of injury. EMS should assess for inhalation injury by looking for singed nasal hairs, burns on the nasal and mouth area, respiratory distress, and sooty sputum. Patients in respiratory distress should be intubated at the site. The patient should have an IV started and fluids, esp in adults. In children accessing small veins in a dark home can be difficult, and transport is recommended. Local cooling can be applied to relieve pain.

The first step is to immediately stop the burning process by removing burning and hot items from skin contact. Small areas of burn can be cooled with liquids like tap water or saline solution. If the patient has larger burns, be cautious of extensive cooling as this could lead to hypothermia. Superficial burns need little more than over-the-counter pain medicine, topical analgesics, or topical aloe vera. Partial-thickness and full-thickness burns are treated with cleansing, topical antibiotic ointments or occlusive dressings, pain medications, and tetanus booster if needed. Patients with severe burn will require fluid resuscitation, oxygen, cardiac monitoring, nasogastric tube, Foley catheter, IV pain medication, a tetanus booster, and transfer to a burn center. If patients are transferring to a burn center, simply cleaning and covering the burns without topical creams or ointments is all that is usually needed. It is best to contact the burn center for instructions.[13][14]

Inhalation injury must be ruled out in the ED. Inhalation injury can lead to upper airway edema within 12 to 24 hours, and the recommendation is for intubation if there is any doubt. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is possible, as it does provide an accurate way to determine inhalation injury. Following control of the airway, one should perform a vertical incision of the eschar on the chest to prevent limitations of chest expansion. Sometimes additional lateral incisions may be required depending on the degree of eschar formation.

All circumferential full-thickness burn injuries need an escharotomy to prevent compartment syndrome.

Levels of carbon monoxide and cyanide need to be measured, and patients provided with oxygen. One should suspect cyanide toxicity in the presence of severe metabolic acidosis, normal arterial oxygen, and low carboxyhemoglobin.

All burns larger than 20% TBSA need fluid resuscitation based on the parkland formula. Crystalloids are preferable to colloids. One should be careful not to overhydrate and cause ARDs. Since there is a significant amount of protein loss during a burn, some centers do infuse 5% albumin. A foley should be inserted for the strict assessment of fluid balance.

Debate continues over the best way to treat blisters. Large blisters, tense blister, and blister crossing joints require debridement while small blisters and blisters involving the palms or soles are left intact.

One method of treating partial-thickness burns is to cover them with topical antibiotic ointments, like bacitracin or triple-antibiotic ointment, and then apply a simple absorbent dressing. The ointment can be spread on the dressing like peanut butter on bread, then placed on the burn. Dressings are changed once or twice a day and may take 1 to 2 weeks to heal. Silver sulfadiazine has historically been a commonly used topical antibiotic cream but is falling out of favor with growing evidence it can delay healing. The other method of burn wound management is to apply a specialized occlusive burn dressing to the burn and leave this in place for about one week.

After stabilization of the patient, surgical debridement and grafting are necessary.

Nutritional support is critical because the basal energy expenditure is high. Early enteral nutrition is the recommendation to prevent bacterial translocation from the gut. The patient's caloric requirement can be estimated by using the Curreri formula (25kcal/kg+40kcal/% TBSA).

Skin discoloration is a common problem after a burn and a source of severe distress. Epidermal grafts are an option, but this is also time-consuming and expensive.

Because burns are dynamic injuries, they are difficult to assess on the initial exam accurately. Patients with burns should be reexamined in several days to reassess both the extent and depth of the burns.

Differential Diagnosis

- Chemical burn

- Electric burn

- Heat/fire burn

Prognosis

The prognosis following a burn depends on many factors. While first degree burns have a good prognosis, both second and third-degree burns can have high morbidity and mortality. Extremes of age, other comorbidities, facility experience, and presence of inhalation injury play a significant role in the outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of a thermal burn is with an interprofessional team that consists of an emergency department physician, burn nurse, dietitian, ophthalmologist, dermatologist, and plastic surgeon.

The initial treatment is done in the emergency room to stop the process of burning and to resuscitate the patient. Depending on the depth and extent of the burn, admission may be required. Since these patients are prone to infections, an infectious disease consultant should be involved in the care of the patient. Those who suffer inhalation injury may need ventilation and management in the ICU.

The care for extensive second and third-degree burns is always a prolonged process, and some patients may require multiple plastic surgery procedures to cover the skin area burn. A wound care nurse should be involved early in the care. These patients need regular dressing changes for weeks or months. Additionally, nutrition is critical, and thus a dietitian should be consulted. Physical therapy should exercise the limbs to prevent contractures. The pharmacist should be involved in pain management.

Because cosmesis becomes altered, it is essential to seek a mental health consultation for the patient before discharge. The entire team should communicate with each member so that the goals of treatment are unified and meet the standard of care. With this approach, hopefully, the morbidity of burns can be reduced.

The outcomes depend on the type and extent of the burn. Those with first degree burns have an excellent prognosis, but those with second and third-degree burns, the prognosis is fair to guarded.[15][16] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brink C, Isaacs Q, Scriba MF, Nathire MEH, Rode H, Martinez R. Infant burns: A single institution retrospective review. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Nov:45(7):1518-1527. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.11.005. Epub 2019 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30638666]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReid A, Ha JF. Inhalational injury and the larynx: A review. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Sep:45(6):1266-1274. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.10.025. Epub 2018 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 30529118]

Regan A, Hotwagner DT. Burn Fluid Management. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30480960]

Jones CD, Ho W, Gunn E, Widdowson D, Bahia H. E-cigarette burn injuries: Comprehensive review and management guidelines proposal. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Jun:45(4):763-771. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.09.015. Epub 2018 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 30442380]

Gentges J, Schieche C, Nusbaum J, Gupta N. Points & Pearls: Electrical injuries in the emergency department: an evidence-based review. Emergency medicine practice. 2018 Nov 1:20(Suppl 11):1-2 [PubMed PMID: 30383348]

Gentges J, Schieche C. Electrical injuries in the emergency department: an evidence-based review. Emergency medicine practice. 2018 Nov:20(11):1-20 [PubMed PMID: 30358379]

Huang HH, Lee YC, Chen CY. Effects of burns on gut motor and mucosa functions. Neuropeptides. 2018 Dec:72():47-57. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2018.09.004. Epub 2018 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 30269923]

Dado DN, Huang B, Foster DV, Nielsen JS, Gurney JM, Morrow BD, Sharma K, Chung KK, Ainsworth CR. Management of calciphylaxis in a burn center: A case series and review of the literature. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Feb:45(1):241-246. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.09.008. Epub 2018 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 30322738]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBadulak JH, Schurr M, Sauaia A, Ivashchenko A, Peltz E. Defining the criteria for intubation of the patient with thermal burns. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2018 May:44(3):531-538. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.02.016. Epub 2018 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 29548862]

Clark A, Neyra JA, Madni T, Imran J, Phelan H, Arnoldo B, Wolf SE. Acute kidney injury after burn. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2017 Aug:43(5):898-908. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2017.01.023. Epub 2017 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 28412129]

Struck HG. [Chemical and Thermal Eye Burns]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2016 Nov:233(11):1244-1253 [PubMed PMID: 27454309]

Ottomann C, Hartmann B, Antonic V. Burn Care on Cruise Ships-Epidemiology, international regulations, risk situation, disaster management and qualification of the ship's doctor. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2016 Sep:42(6):1304-10. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.01.032. Epub 2016 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 27344547]

Vivó C, Galeiras R, del Caz MD. Initial evaluation and management of the critical burn patient. Medicina intensiva. 2016 Jan-Feb:40(1):49-59. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2015.11.010. Epub 2015 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 26724246]

Píriz-Campos RM, Martín Espinosa NM, Postigo Mota S. [Therapeutic guide to critical burn patients]. Revista de enfermeria (Barcelona, Spain). 2014 Feb:37(2):39-42 [PubMed PMID: 24738172]

Jaspers MEH, van Haasterecht L, van Zuijlen PPM, Mokkink LB. A systematic review on the quality of measurement techniques for the assessment of burn wound depth or healing potential. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Mar:45(2):261-281. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.05.015. Epub 2018 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 29941159]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMauck MC, Smith J, Liu AY, Jones SW, Shupp JW, Villard MA, Williams F, Hwang J, Karlnoski R, Smith DJ, Cairns BA, Kessler RC, McLean SA. Chronic Pain and Itch are Common, Morbid Sequelae Among Individuals Who Receive Tissue Autograft After Major Thermal Burn Injury. The Clinical journal of pain. 2017 Jul:33(7):627-634. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000446. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28145911]