Introduction

Ageusia is a rare condition that is characterized by a complete loss of taste function of the tongue. It requires differentiation from other taste disorders such as hypogeusia (decreased sensitivity to all tastants), hyperguesia (enhanced gustatory sensitivity), dysgeusia (unpleasant perception of a tastant), and phantogeusia (perception of taste that occurs in the absence of a tastant). Although ageusia is not a life-threatening condition, it can cause discomfort. It can lead to loss of appetite, reduction in weight, and in some cases, may require discontinuation of drugs in already compromised patients; this can result in medical problems and can have a severe psychological impact on the patient.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are a variety of conditions that can lead to ageusia, such as damage to the nerve of taste sensation (lingual and glossopharyngeal nerve) in the anterior and posterior portion, dietary deficiencies, systemic conditions such as hypothyroidism, and diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, Sjogren syndrome, and Crohn disease. Cranial nerve lesions affecting gustatory function include neuritis due to herpes zoster, dissection of the cervical arteries, space-occupying processes in the cerebellopontine angle (meningioma or neurinoma), and the neoplastic lesions affecting the skull base. It can also result from iatrogenic lesions (following laryngoscopic manipulations), neuralgia, and polyneuropathies (due to conditions such as diphtheria, porphyria, lupus, or amyloidosis).

Patients with cancer in any head and neck region receiving radiotherapy can present with ageusia as radiation therapy can injure the taste buds, transmitting nerves, and affect the salivary flow by damaging the salivary glands, resulting in gustatory dysfunction.

Zinc deficiency is also responsible for abnormalities in taste perception in an otherwise healthy person and cases of drug-induced taste disorders. It can also result from some local injury and inflammation in the surrounding structure. The damage can be a result of burns, lacerations, surgery, and local anesthesia). Taste function can also be affected by local antiplaque medicaments that get excreted into saliva, some infections (dentoalveolar, periodontal, and soft tissue infections), vesiculobullous conditions, complete and partial removable prostheses, metallic dental restorations, and dysfunction of the salivary gland.

Certain drugs including antibiotics (ampicillin, macrolides, metronidazole, quinolones, tetracycline), antineoplastic agents, neurologic medications (anti parkinsonism, CNS stimulants, migraine medications) cardiovascular drugs (antihypertensives, diuretics, statins, antiarrhythmics), antipsychotics, tranquilizers, tricyclic antidepressants, thyroid medications, antihistamines, bronchodilators, antifungals, and antivirals have also been reported to cause ageusia as a side effect.[1]

Moreover, aging or factors associated with aging may also render individuals more vulnerable to dysfunction of the gustatory system.

Epidemiology

Complete ageusia is very rare. It has been reported to occur in 1 or 2 people out of 1000. In general, the gustatory function decreases with advancing age. However, it usually does not lead to complete loss of taste.

Pathophysiology

The sense organ specialized for taste consists of 10000 taste buds approximately. These taste buds are ovoid bodies and measure about 50 to 70 micrometers. The taste buds appear in various anatomic locations, such as in the mucosa of the epiglottis, palate, pharynx, and the papillae of the tongue. At the apical portion of each taste bud are receptors that get exposed to the oral cavity. Within each taste bud lie four morphologically distinct types of cells (Basal cells, type I dark cells, Type I light cells, and Type III intermediate cells. Basal cells are likely to be immature taste cells that do not extend processes into the taste pore. The latter three types of cells are sensory neurons, and they are responsible for responding to taste stimuli or tastants.

The pathophysiology of ageusia depends on the factor leading to its cause. In a person undergoing chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment, anatomic changes in taste bud cells and sometimes death of taste bud cells can occur due to the higher rate of cell turnover. Also, as saliva is essential for transporting stimulants to the taste cells, damage to the major salivary glands during the treatment of cancer can lead to a loss of taste. The presence of infection or inflammation in the nearby areas may trigger apoptosis, which can lead to a reduction in the number of taste bud cells. They may also disrupt the ability to detect taste stimulants by chemosensitive hairs.[2]

Injury to the chorda tympani nerve during an ear surgery, laryngoscopy, or any dental surgical treatment can lead to changes in the taste perception. The presence of any infection or trauma can also lead to injury of this nerve carrying the sensory taste fibers from the tongue. Any damage to the lingual branch of the ninth cranial nerve during tonsillectomy may also result in taste loss.[3][4] The taste bud cells become altered in certain systemic disorders which can secondarily lead to loss of taste through neuropathy or changes in the environment of the oral cavity. The disorders include autoimmune diseases (Sjogren syndrome), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal disorder, liver disorder, and hyperthyroidism.[5][6]

The normal aging process can also lead to a decline in the taste perception, but complete taste loss is rare. A reduction in taste sensation among elderly patients is common because of age-related regression in taste cells, reduced production of saliva, and an individual’s inability to chew food completely correlates with tooth loss.[7] Also, geriatric patients are affected by ageusia due to polypharmacy, dietary deficiency, and as a secondary complication of some oral and systemic disease.

The gustatory nucleus is a paired nucleus located in the medulla; these are also referred to as solitary nuclei. They receive impulses from the taste buds present on the tongue through VII, IX and X cranial nerves. After receiving these impulses, the nuclei send profuse projections to various regions of the brain such as the amygdala, pons, lateral hypothalamus, ventral posterior thalamic nucleus as well as to the primary and secondary gustatory cortical regions.

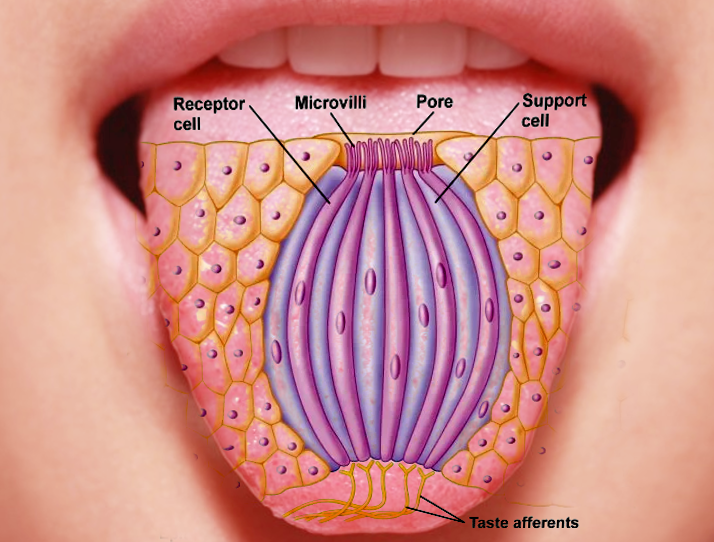

Histopathology

Taste buds contain epithelial-derived taste receptor cells and sustentacular cells. These cells surround a small cavity in the center that opens onto the surface as a tiny taste pore, and both get renewed by the basal cells. Chemicals present in the food stimulate the taste receptor cells, which convert the taste stimuli into electrochemical signals. They then transmit these signals to the sensory nerves.

History and Physical

When examining patients with gustatory dysfunction, subjective assessment of the chief complaint along with the objective evaluation of the head, neck, and oral region and review of the patient's medical condition, dental condition, current, and past medications, and social history is necessary.

Detailed history: To identify the etiology of the disease, the events associated with the onset of the gustatory complaint are of utmost importance. A complete history, including systemic illness, current medication, and dental procedures, also merits consideration.[8] Any change in the medication also requires evaluation.

Physical examination: To identify the local factors leading to the development of the gustatory disorder, the oral cavity needs an examination for local factors.[8]

Apart from this, there are various tests available for assessment of taste sensation, such as electro/chemo-gustometry and spatial analyses. The electrogustometry has its basis the principle of applying weak electrical currents to the different taste buds in the oral cavity, whereas the chemogustometry uses specific taste solutions to examine the taste sensitivity. Based on these tests, the patient's ability to identify and evaluate the intensity of different types of tastes, such as sweet, salty, sour, and bitter taste gets assessed. Since the localized areas of impairment can be undetected, in the spatial test, different regions of the mucosa of the oral cavity get evaluated. In this test, a cotton swab is dipped in a particular taste solution and then applied to different areas of the oral mucosa. To assess the efficiency of the taste buds present on the throat, the patient is asked to swallow part of each taste solution. The patient is then asked to assess the quality and intensity of the taste.

Some other tests include the use of stimuli in the form of a filter paper saturated with tastant/taste strips. The patient is then asked to identify the taste. The strips have an advantage over the taste solution of having a long shelf life.

The clinician can also evaluate gustatory dysfunction by applying a topical anesthetic (unflavored 2% lidocaine) on the dorsal surface of the tongue. The anesthetic is applied on one side, first starting from the anterior two-third and progressing toward the posterior one-third, followed by application to the contralateral side in the same manner. If the chief complaint gets eliminated, the source of taste disorder is considered to be local. But if it persists, then other factors such as a systemic condition or some lesion in the central nervous system may be suspected.

Evaluation

Apart from history and physical examination, psychophysical and medical imaging can also take place in the clinical assessment of a patient with gustatory disorder.

Psychophysical evaluation: This is essential to identify the patient's complaints and in measuring the degree of permanent taste loss. The clinician must also be sensitive to the psychological state of the patient. Depression can result from a taste problem or contribute to a taste complaint.[8]

Medical Imaging: This is done to obtain anatomical and etiological diagnostic information. Imaging techniques help in ruling out or confirm the presence of any damage to the structures of the central nervous system, particularly to the brain stem, thalamus, or pons.

Treatment / Management

Determination of the etiological factor is necessary to treat ageusia. Some taste disorders do not require any treatment as they resolve spontaneously. There is no particular therapeutic regime for a taste disorder like ageusia. If it is chemotherapy-induced, it is potentially reversible by the cessation of the use of offending medication. However, discontinuation of drugs to treat the taste disorder is not always possible in patients, particularly with life-threatening conditions such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, and uncontrolled infections. Supplements are an option, such as zinc gluconate, particularly in patients undergoing radiotherapy/chemotherapy in the dosage of 140mg/day or alpha-lipoic acid[9] in the dosage of 600 mg/day for few months may restore taste.

In cases of dysgeusia and burning mouth disorder, tricyclic antidepressants and clonazepam are a possibility. With severe dysgeusia, topical anesthetics such as lidocaine gel may help. Following trauma or surgery affecting the nerve supply to the taste buds, no specific therapy is available. The condition may either improve gradually on its own or may remain the same. In patients with xerostomia, an artificial saliva is a therapeutic option.

Differential Diagnosis

While diagnosing ageusia, it is essential first to distinguish whether there is a total loss of taste or attenuation of a specific taste. The medical history of the patient is significant in arriving at the diagnosis. It must take into account the concerned diseases of the nose, nasal sinus, any recent viral infection, allergy, presence of any contaminant at the area of work (e.g., vapor), and intake of drugs. Etiopathogenetically it has broad differential diagnostic considerations. Various factors should be considered, such as drugs and physical agents, cerebrovascular disorders, tumor, head trauma, and fracture of the skull base. Also, as the normal aging process can also lead to diminished taste perception, this should be considered.

Staging

Some authors have created a staging system to assess whether the patient has ageusia or dysgeusia. A scale that ranges from 0, which refers to total taste loss or ageusia, to 3, which refers to no taste loss, may be useful in evaluation.[10]

Prognosis

The success rate of the treatment of ageusia depends upon the etiology. Many patients develop depression as they remain concerned about the seriousness of their disorder.

Complications

Ageusia can create serious health issues. Ageusia, if induced by drugs, can lead to worsening of various geriatric problems such as anorexia, cachexia, and incontinence. It can be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular stroke, and other illnesses that require a specific diet.

When the taste sensation is affected, the person may change his/her eating habits and may have a dietary deficiency. Some people may eat less resulting in loss of weight, while others may eat in higher quantity resulting in weight gain. In severe cases, ageusia can lead to depression.

Consultations

Patients with taste disorders should be referred to experts of various specialists if his/her quality of life is significantly impaired by a persistent gustatory condition, particularly that has no easily identifiable and treatable cause.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Ageusia can have a significant impact on the individual's psychological status and health, particularly in elderly patients. Sometimes, a cure is often challenging to obtain. In such cases, the most crucial aspect of treatment is educating the patient on how to cope with the disorder. Some of the strategies that may be useful for patients with ageusia include eating smaller and more frequent meals, use of more condiments, utilization of more fats and sauces, and oral care.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are many causes of ageusia, and the diagnosis is often not made by clinicians. Thus, it is essential to have an interprofessional team to manage patients with ageusia to avoid high morbidity. Since many medications can cause ageusia, the clinician should consult with a pharmacist for a medication review to check if this may be the source. However, the pharmacist should not discontinue any drugs as they may be necessary to manage a severe disorder. Instead, the patient should obtain a referral to a specialist for further workup. Nurses should be aware that ageusia is common in the elderly but often requires no specific treatment other than hydration and the use of artificial saliva. They should report their findings to the clinical team and work with the team to provide some treatment if possible.

Continuous research work is essential to develop a better understanding of the nature, frequency, duration, and etiology of ageusia and their impact on food consumption and malnutrition in the patients. Since gustatory dysfunctions present several diagnostic difficulties to the clinicians, future research is required to improve diagnostic procedures. However, a clinician must be prepared to properly evaluate and treat ageusia or refer the patient if needed. Open communication between the interprofessional team is vital to lower the morbidity of ageusia. [Level V]

Media

References

Deguchi K, Furuta S, Imakiire T, Ohyama M. Case of ageusia from a variety of causes. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1996 Jun:110(6):598-601 [PubMed PMID: 8763388]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang H, Zhou M, Brand J, Huang L. Inflammation and taste disorders: mechanisms in taste buds. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009 Jul:1170():596-603. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04480.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19686199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoins MR, Pitovski DZ. Posttonsillectomy taste distortion: a significant complication. The Laryngoscope. 2004 Jul:114(7):1206-13 [PubMed PMID: 15235350]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLandis BN, Scheibe M, Weber C, Berger R, Brämerson A, Bende M, Nordin S, Hummel T. Chemosensory interaction: acquired olfactory impairment is associated with decreased taste function. Journal of neurology. 2010 Aug:257(8):1303-8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5513-8. Epub 2010 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 20221768]

Bromley SM. Smell and taste disorders: a primary care approach. American family physician. 2000 Jan 15:61(2):427-36, 438 [PubMed PMID: 10670508]

Kusaba T, Mori Y, Masami O, Hiroko N, Adachi T, Sugishita C, Sonomura K, Kimura T, Kishimoto N, Nakagawa H, Okigaki M, Hatta T, Matsubara H. Sodium restriction improves the gustatory threshold for salty taste in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2009 Sep:76(6):638-43. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.214. Epub 2009 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 19516246]

Boyce JM, Shone GR. Effects of ageing on smell and taste. Postgraduate medical journal. 2006 Apr:82(966):239-41 [PubMed PMID: 16597809]

Cowart BJ. Taste dysfunction: a practical guide for oral medicine. Oral diseases. 2011 Jan:17(1):2-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01719.x. Epub 2010 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 20796233]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 30859990]

Maes A, Huygh I, Weltens C, Vandevelde G, Delaere P, Evers G, Van den Bogaert W. De Gustibus: time scale of loss and recovery of tastes caused by radiotherapy. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2002 May:63(2):195-201 [PubMed PMID: 12063009]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence