Introduction

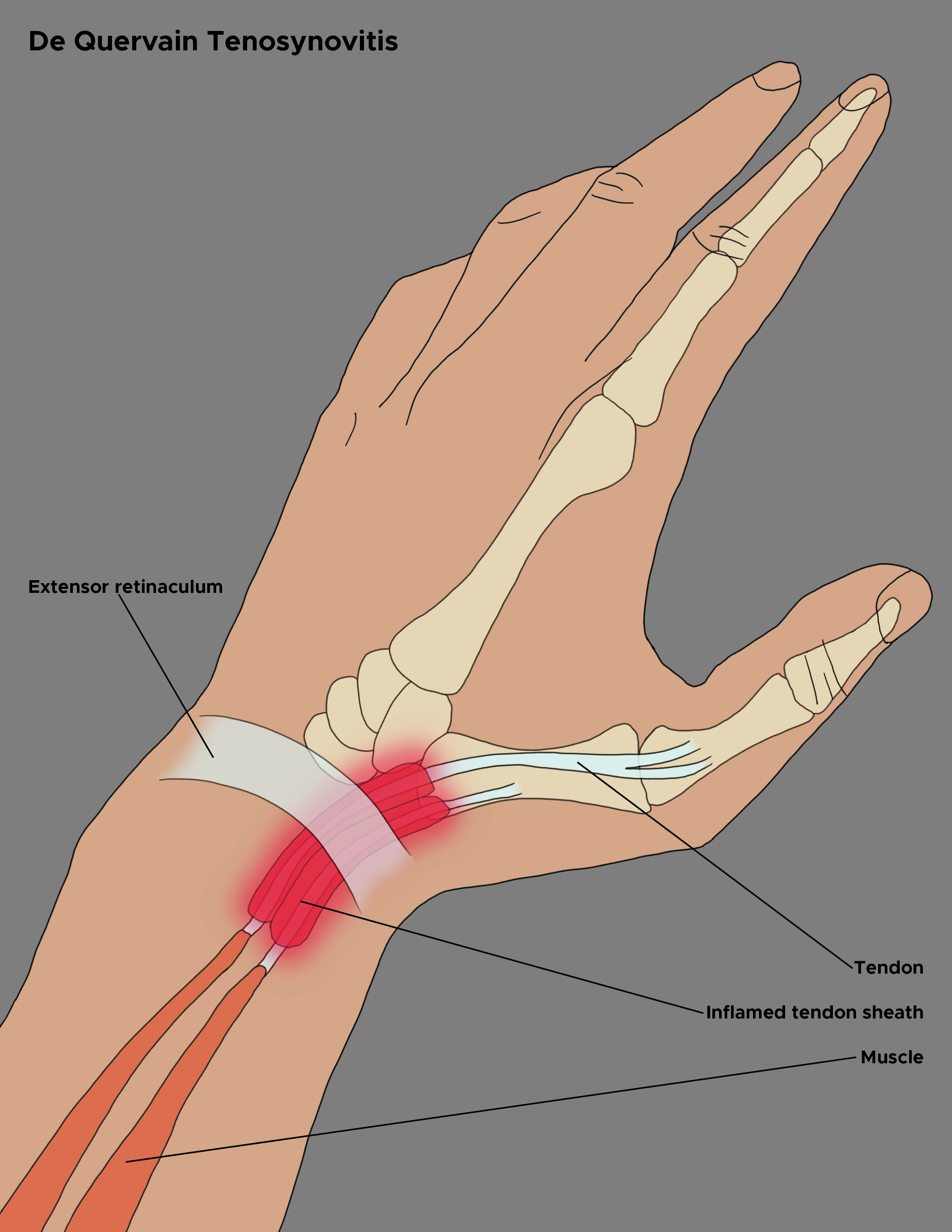

De Quervain tenosynovitis, named after Swiss surgeon Fritz de Quervain, is a condition that involves tendon entrapment affecting the first dorsal compartment of the wrist. With this condition, thickening and myxoid degeneration of the tendon sheaths around the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis develop where the tendons pass in through the fibro-osseous tunnel located along the radial styloid at the distal wrist.[1] Pain is exacerbated by thumb movement and radial and ulnar deviation of the wrist.[2][3] The condition typically affects women in the late pregnancy or the postpartum period.[4]

The management starts with nonoperative treatment in the form of immobilization and corticosteroid injection in the first dorsal compartment. The majority of the patients benefit from conservative treatment. In patients where nonoperative treatment doesn't provide pain relief, surgical release of the first dorsal compartment is indicated.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

While the exact cause of de Quervain tenosynovitis is unclear, it has been attributed to myxoid degeneration with fibrous tissue deposits and increased vascularity rather than acute inflammation of the synovial lining. This deposition results in the thickening of the tendon sheath, painfully entrapping the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons. It is associated with repetitive wrist movements, specifically requiring thumb radial abduction, simultaneous extension, and radial wrist deviation. The classic patient population is mothers of newborns who repeatedly lift a newborn with thumbs radially abducted and wrists going from ulnar to radial deviation.[6] Some possible etiologies for the disease include acute injury to the wrist, increased frictional forces to the wrist by forceful movements of the wrist and the thumb, pathogenic causes, inflammatory ailments, and anatomical variations in the first dorsal compartment.[7][8]

Epidemiology

One study estimated the prevalence of de Quervain tenosynovitis to be 0.5% in men and 1.3% in women, with peak prevalence among those in their forties and fifties.[9] Another study determined the prevalence to be 0.36% in women and 0.13% in men.[10] The condition may be seen more commonly in individuals with a history of medial or lateral epicondylitis. Bilateral involvement is often reported in new mothers or child care providers in whom spontaneous resolution typically occurs once lifting of the child is less frequent.[11][12] Pregnancy and manual labor are two significant risk factors for the disease.[13]

Pathophysiology

The extensor tendons of the wrist are divided into 6 extensor compartments by the extensor retinaculum.[5] The first dorsal compartment of the wrist contains the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons lined by a synovial sheath that separates it from the five other dorsal wrist compartments. As these tendons pass through an approximately 2 cm long fibrous tunnel passing over the radial styloid and under the transverse fibers of the extensor retinaculum, they are at risk for entrapment, particularly in acute trauma or repetitive motion.[8][14] The first compartment gets shrunk due to the thickening of the tendon sheath, causing a "stenosing" tenosynovitis of the wrist.[4]

There is a formation of fibrocartilage in response to the increased stress over the tendon sheaths, leading to its thickening. There is neovascularization seen over the tendon sheaths. Myxoid degeneration is also seen in the tendons in this condition. A septum is often seen in the first dorsal compartment between the two tendons, which not only constricts the volume of the first compartment but also has important considerations in nonoperative as well as operative treatment.[15]

History and Physical

Patients present with radial-sided wrist pain typically worsened by thumb and wrist motion. The condition may be associated with pain or difficulty opening a jar lid. Tenderness overlying the radial styloid is usually present. If present, the swelling over the wrist is generally seen proximal to the radial styloid. The typical patient population is a pregnant woman in the third trimester or a breastfeeding mother who holds her child repeatedly.[16]

There are various provocative clinical tests described for de Quervain tenosynovitis. The Finkelstein test requires the patient to place the thumb in palmar flexion while the examiner does ulnar deviation of the wrist. A positive test is indicated by the induction of sharp pain along the radial wrist at the first dorsal compartment. The Eichhoff test involves asking the patient to clench the thumb with the other fingers while deviating the wrist towards the ulna, which elicits a sharp shooting pain over the radial aspect of the wrist if positive. The WHAT test (causing wrist hyperflexion and thumb abduction) is another provocative clinical test described for this condition.[1]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of de Quervain tenosynovitis is a clinical one based on the typical history and examination findings. While not helpful in confirming the diagnosis, plain radiographs may help differentiate other causes of radial wrist pain, such as thumb carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis.[17][18] Ultrasonography of the wrist helps in the identification of the septum in the first dorsal compartment, the elucidation of which helps increase the success rates of corticosteroid injections. When opting for surgical management, preoperative identification of the septum through ultrasonography is helpful, as both the subcompartments need to be released to provide effective pain relief.[5]

Treatment / Management

De Quervain tenosynovitis can be self-limiting and may resolve without intervention. For those individuals with persistent symptoms, splinting, systemic anti-inflammatories, and corticosteroid injections are the most frequently utilized nonsurgical treatment options. Splinting with a thumb spica brace may offer patients temporary relief, but failure and recurrence are often high, and compliance is often low.[19][20][21] Splinting may be a temporary measure for patients who don't want to opt for any intervention. Immobilization of the wrist alone may only help relieve pain in patients with mild pain. Moreover, strict immobilization in a thumb spica cast or rigid splint may prove detrimental as it might increase the myxoid degeneration of the involved tendons. Therefore, immobilization in a removable semi-rigid splint may be more helpful.[1](A1)

Corticosteroid injection has been reported to provide near complete relief with one or two injections in 52% to 90% of patients.[22] The injection is performed into the tendon sheath 1 cm proximal to the radial styloid, where the tendons are palpable. An attempt should be made to palpably infiltrate both the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis sheaths as deep as possible in the fibro-osseous tunnel to minimize the risk of subcutaneous atrophy and hypopigmentation. Ultrasound guidance during injection has been reported to allow visualization and adequate injection of the multiple septae and sheaths, which may be present in the first dorsal extensor compartment. The success rate of the corticosteroid injection increases when the procedure is performed under ultrasound guidance.[23] Symptomatic relief is reported by about 50% of patients with a single injection. A second injection may provide relief in another 40% to 45% of patients. Potential steroid injection complications include fat and dermal atrophy and hypopigmentation, typically associated with subcutaneous injection rather than in the tendon sheath. These may improve or resolve over time. Also, multiple injections within a short period may cause weakening of the tendons, causing their thinning and eventual rupture.(A1)

Various other nonoperative treatment modalities have also been described in the form of laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound therapy, and acupuncture, but there is no consensus or high-quality evidence about the effectiveness of these therapies.[24](A1)

If symptoms fail to improve or recur after two corticosteroid injections, operative management is an option. Surgery is usually performed in the outpatient setting. It can entail local, regional, or general anesthesia and typically involves a tourniquet to limit intraoperative bleeding and allow for the identification of critical anatomic structures. This is performed through an approximately 2 cm transverse skin incision over the first dorsal compartment. Using caution to avoid injury to the branches of the superficial radial sensory nerve, the ligament covering the first dorsal compartment is exposed through blunt dissection. The dorsal margin of the sheath is then sharply incised. Subsheaths are identified and incised if present. Once all subcompartments are released, the skin is closed, a bulky, soft dressing is applied, and early mobilization is performed. Multiple variations of surgical techniques have been reported in the literature, including endoscopic approaches and partial excision of the extensor retinaculum. Regardless of the method, high rates of symptomatic relief are reported with low rates of complications.[4](A1)

Post-operative care is usually limited. A simple dressing or wrap is frequently utilized without complex wound care. Patients are advised to begin early use for activities of daily living and other light activities. Once sutures are removed, usually by two weeks, patients are typically released to resume normal activities. Patients may experience mild swelling and tenderness at the surgical site for a few months.

Surgical complications are infrequent but do occur. Local soft tissue infection and wound dehiscence are the most frequent but are typically managed with nonoperative interventions, including oral antibiotics and local wound care, respectively. The superficial radial nerve overlying the first dorsal compartment can be injured due to sharp transection, traction injury, or compression related to scarring. This can result in extreme sensitivity, pain, and paresthesias. While sometimes self-limited, this can rarely require surgical intervention for neurolysis or treatment of a neuroma. Following the release, patients may also experience subluxation of the first dorsal compartment tendons with wrist flexion and extension. This may be bothersome when the tendons rub or sublux over the radial styloid. This may be associated with excessive release of the tendon sheath at the time of surgery. Hypertrophic scarring is another complication seen with the operative management of this condition.[4][5][1](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses that can mimic this condition include:

- Osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint

- Scaphoid fracture

- Radial styloid fracture

- Sensory branch of radial nerve neuritis (Wartenberg's syndrome)

- Intersection syndrome

- Trigger thumb

Prognosis

Most patients are treated successfully with nonoperative management. Corticosteroid injection, with or without immobilization, is effective in many patients. Even when the nonoperative command fails, releasing the first dorsal compartment relieves pain in almost all patients. Hence, the prognosis is usually good for these patients. Certain risk factors for failure of nonoperative treatment include the female sex, hypothyroidism, presence of septum in the first compartment, and psychiatric illness.

Complications

Complications related to surgery include:

- Injury to the superficial radial nerve

- Entrapment of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis

- Subluxation of the tendons

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patients should be educated about the risk factors of the disease, its treatment options, and potential complications. When multiple steroid injections are required, they should be adequately spaced out by a few weeks to prevent the possible complications associated with the injections.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

De Quervain tenosynovitis is a relatively common disorder. The patient may present to several specialists, including a hand surgeon, orthopedic surgeon, primary care provider, or an emergency room physician. Nurses may encounter this disorder at workers' compensation clinics and rehabilitation centers. Finally, some patients may present to a pharmacist and ask for a pain reliever. The key is to make the diagnosis promptly and avoid the morbidity of the condition.

For patients who seek treatment, the outcomes are excellent. For patients who don't get treatment, the resulting pain often results in disability. Surgery has the best outcome but can cause complications. Cortisone injections do work, but recurrences are known to occur. In addition, with cortisone injections, the recovery may take 3 to 9 months. All patients should avoid repetitive actions to prevent the recurrence of symptoms. Some patients may need a job change, and others may need to enroll in long-term hand rehabilitation exercises.[3][25]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Larsen CG, Fitzgerald MJ, Nellans KW, Lane LB. Management of de Quervain Tenosynovitis: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS reviews. 2021 Sep 10:9(9):. doi: e21.00069. Epub 2021 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 34506345]

Skef S, Ie K, Sauereisen S, Shelesky G, Haugh A. Treatments for de Quervain Tenosynovitis. American family physician. 2018 Jun 15:97(12):Online [PubMed PMID: 30216006]

Ippolito JA, Hauser S, Patel J, Vosbikian M, Ahmed I. Nonsurgical Treatment of De Quervain Tenosynovitis: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2020 Mar:15(2):215-219. doi: 10.1177/1558944718791187. Epub 2018 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 30060681]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSuwannaphisit S, Chuaychoosakoon C. Effectiveness of surgical interventions for treating de Quervain's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2022 May:77():103620. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103620. Epub 2022 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 35638053]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAllbrook V. 'The side of my wrist hurts': De Quervain's tenosynovitis. Australian journal of general practice. 2019 Nov:48(11):753-756. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-07-19-5018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31722458]

Shuaib W, Mohiuddin Z, Swain FR, Khosa F. Differentiating common causes of radial wrist pain. JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2014 Sep:27(9):34-6. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000451875.71319.17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25148441]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee KH, Kang CN, Lee BG, Jung WS, Kim DY, Lee CH. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the first extensor compartment of the wrist in de Quervain's disease. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. 2014 Jan:19(1):49-54. doi: 10.1007/s00776-013-0481-3. Epub 2013 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 24132793]

Fedorczyk JM. Tendinopathies of the elbow, wrist, and hand: histopathology and clinical considerations. Journal of hand therapy : official journal of the American Society of Hand Therapists. 2012 Apr-Jun:25(2):191-200; quiz 201. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2011.12.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22507213]

Stahl S, Vida D, Meisner C, Lotter O, Rothenberger J, Schaller HE, Stahl AS. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the work-related cause of de Quervain tenosynovitis: a critical appraisal of its recognition as an occupational disease. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 Dec:132(6):1479-1491. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000434409.32594.1b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24005369]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShen PC, Chang PC, Jou IM, Chen CH, Lee FH, Hsieh JL. Hand tendinopathy risk factors in Taiwan: A population-based cohort study. Medicine. 2019 Jan:98(1):e13795. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013795. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30608391]

Stahl S, Vida D, Meisner C, Stahl AS, Schaller HE, Held M. Work related etiology of de Quervain's tenosynovitis: a case-control study with prospectively collected data. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2015 May 28:16():126. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0579-1. Epub 2015 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 26018034]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLaoopugsin N, Laoopugsin S. The study of work behaviours and risks for occupational overuse syndrome. Hand surgery : an international journal devoted to hand and upper limb surgery and related research : journal of the Asia-Pacific Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand. 2012:17(2):205-12 [PubMed PMID: 22745084]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIlyas AM, Ast M, Schaffer AA, Thoder J. De quervain tenosynovitis of the wrist. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2007 Dec:15(12):757-64 [PubMed PMID: 18063716]

Hazani R, Engineer NJ, Cooney D, Wilhelmi BJ. Anatomic landmarks for the first dorsal compartment. Eplasty. 2008:8():e53 [PubMed PMID: 19092992]

Lee ZH, Stranix JT, Anzai L, Sharma S. Surgical anatomy of the first extensor compartment: A systematic review and comparison of normal cadavers vs. De Quervain syndrome patients. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2017 Jan:70(1):127-131. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.08.020. Epub 2016 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 27693273]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSato J, Ishii Y, Noguchi H. Clinical and ultrasound features in patients with intersection syndrome or de Quervain's disease. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2016 Feb:41(2):220-5. doi: 10.1177/1753193415614267. Epub 2015 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 26546605]

Wu F, Rajpura A, Sandher D. Finkelstein's Test Is Superior to Eichhoff's Test in the Investigation of de Quervain's Disease. Journal of hand and microsurgery. 2018 Aug:10(2):116-118. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1626690. Epub 2018 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 30154628]

Hubbard MJ, Hildebrand BA, Battafarano MM, Battafarano DF. Common Soft Tissue Musculoskeletal Pain Disorders. Primary care. 2018 Jun:45(2):289-303. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29759125]

Foster ZJ, Voss TT, Hatch J, Frimodig A. Corticosteroid Injections for Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. American family physician. 2015 Oct 15:92(8):694-9 [PubMed PMID: 26554409]

D'Angelo K, Sutton D, Côté P, Dion S, Wong JJ, Yu H, Randhawa K, Southerst D, Varatharajan S, Cox Dresser J, Brown C, Menta R, Nordin M, Shearer HM, Ameis A, Stupar M, Carroll LJ, Taylor-Vaisey A. The effectiveness of passive physical modalities for the management of soft tissue injuries and neuropathies of the wrist and hand: a systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2015 Sep:38(7):493-506. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.06.006. Epub 2015 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 26303967]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHuisstede BM, Coert JH, Fridén J, Hoogvliet P, European HANDGUIDE Group. Consensus on a multidisciplinary treatment guideline for de Quervain disease: results from the European HANDGUIDE study. Physical therapy. 2014 Aug:94(8):1095-110. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130069. Epub 2014 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 24700135]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAnderson BC, Manthey R, Brouns MC. Treatment of De Quervain's tenosynovitis with corticosteroids. A prospective study of the response to local injection. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1991 Jul:34(7):793-8 [PubMed PMID: 2059227]

Shin YH, Choi SW, Kim JK. Prospective randomized comparison of ultrasonography-guided and blind corticosteroid injection for de Quervain's disease. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2020 Apr:106(2):301-306. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.11.015. Epub 2019 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 31899117]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFerrara PE, Codazza S, Cerulli S, Maccauro G, Ferriero G, Ronconi G. Physical modalities for the conservative treatment of wrist and hand's tenosynovitis: A systematic review. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2020 Dec:50(6):1280-1290. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.08.006. Epub 2020 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 33065423]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLapègue F, André A, Pasquier Bernachot E, Akakpo EJ, Laumonerie P, Chiavassa-Gandois H, Lasfar O, Borel C, Brunet M, Constans O, Basselerie H, Sans N, Faruch-Bilfeld M. US-guided percutaneous release of the first extensor tendon compartment using a 21-gauge needle in de Quervain's disease: a prospective study of 35 cases. European radiology. 2018 Sep:28(9):3977-3985. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5387-1. Epub 2018 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 29619521]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence