Introduction

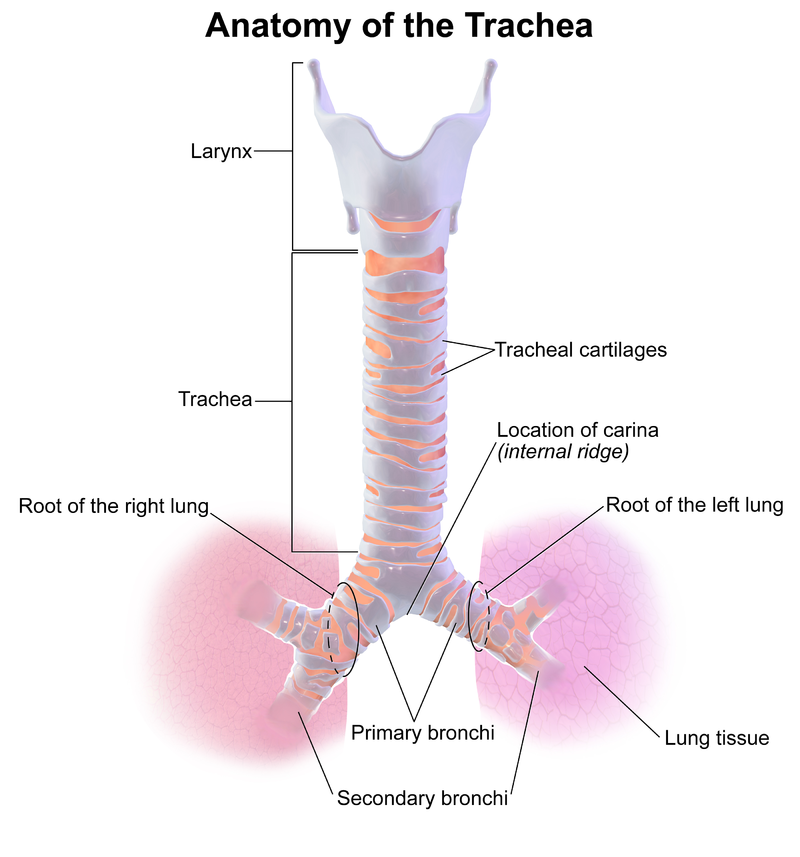

The trachea is a cartilaginous tube beginning at the base of the cricoid cartilage and extending to the carina, which courses through the neck and upper chest to connect the pharynx and larynx to the lungs. It has cervical and thoracic portions, separated at the level of the thoracic inlet above and below, respectively. The trachea bifurcates at the carina into the right and left primary bronchi, through which inspired air is delivered to lung tissue and exhaled. The trachea includes 18 to 22 D-shaped rings, which are cartilaginous anteriorly and laterally and membranous posteriorly. Blood supply to the cervical portions of the trachea comes from the subclavian artery branch, where the artery enters laterally and anastomose superiorly, inferiorly, and anteriorly. The bronchial arteries branching from the aorta provide the blood supply for the thoracic portions. The trachea is near the esophagus, vagus nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerves, thyroid, carotid arteries, jugular veins, innominate arteries and veins, the pulmonary trunk, the azygos vein, and the aorta with the vertebra and spinal cord posteriorly.[1] The study of tracheal injury is often combined with adjacent airway structures (eg, tracheobronchial trauma and laryngotracheal trauma). (see Image. Tracheal Anatomy)

Tracheal trauma is uncommon but is typically caused by iatrogenic, inhalation, penetrating, and blunt injuries that are primarily acute (eg, a stab or crush injury) or subacute (eg, an overinflated endotracheal tube against the trachea for a prolonged period) in duration.[2] Blunt trauma to the neck may result in shearing of the trachea, usually within 3 cm of the carina.[3] Tracheal lacerations can be transverse, spiral, or longitudinal, with varying degrees of tissue involvement.[4] Most experts believe the incidence of tracheal trauma is underestimated as iatrogenic injuries are underreported, and patients with traumatic injuries often die before arriving at the hospital.[5][2] Depending on the mechanism, tracheal trauma may also be associated with trauma to adjacent structures, including bony disruptions of the cervical spine, vascular injury to the great vessels, carotids, jugulars, or digestive tract involvement, and has significant morbidity and mortality.[2] Regardless of the mechanism, early diagnosis and surgical repair are crucial to reducing complications and loss of respiratory function.[6]

A high index of suspicion resulting in the early detection of tracheal trauma is one of the most crucial factors for reducing morbidity and mortality.[7] The clinical presentation of tracheal trauma may vary depending on the mechanism of injury and involvement of adjacent structures. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and pneumothorax with or without respiratory failure are the most common clinical features observed in acute settings. Other symptoms include blood-tinged sputum, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, dysphagia, pneumoperitoneum, and chest pain.[2][5] With a high index of suspicion, the physical and radiographic signs most frequently seen with tracheal injury were dyspnea, pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema.[7] Tracheal trauma management should be tailored to the patient's injuries, clinical presentation, and nature of the tracheal injury, which typically requires the collaboration of a multidisciplinary team.[2] When evaluating a patient with a tracheal injury, the primary initial treatment strategy is proper airway management and treatment of concomitant injuries. A secure airway is best achieved when appropriate by awake intubation over a flexible bronchoscope and placing an endotracheal tube distal to the injury site.[7] Management of laceration repair can then be accomplished either conservatively or surgically depending on the cause of the injury, the depth, and the concomitant injuries sustained.[4][8] Despite early recognition and appropriate management, potential complications include decreased lung function, infection, vocal cord paralysis, and strictures.[9]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

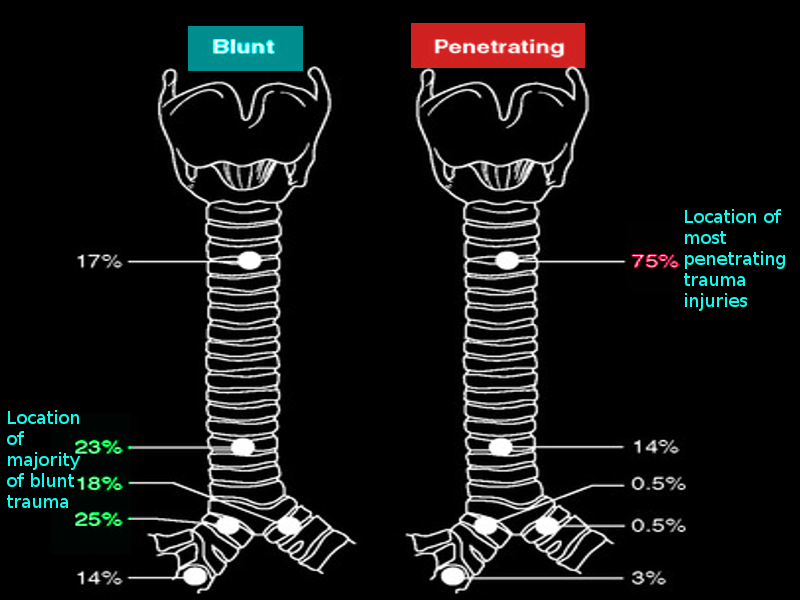

Tracheal trauma is typically caused by iatrogenic, inhalation, penetrating, and blunt injuries that are primarily acute (eg, a stab or crush injury) or subacute (eg, an overinflated endotracheal tube against the trachea for a prolonged period) in duration.[2] Tracheal trauma may follow from either cervical or thoracic injury; cervical injuries tend to be more visible; thoracic injury may go unnoticed. When there is an injury to the tracheobronchial tree, a bronchial injury is more common, especially in blunt trauma, where shearing forces may act on the relatively fixed bronchial structures and disrupt them.[6] (see Image. Locations of Tracheal Injury)

Penetrating injuries: These types of tracheal injuries to the neck and chest should always raise suspicion of potential tracheal trauma and prompt investigation. Although penetrating trauma occurs more frequently in the cervical portions of the trachea, it can occur anywhere along the path of the trachea and involve any of the adjacent structures. More caution is necessary with penetrating gunshot wounds due to the force of the blast.[4]

Blunt force trauma: Blunt trauma is the most common cause of tracheal injury, which may result from direct blows, including compression or strangulation, severe neck flexion or extension, or crush injuries to the chest. Blunt force trauma most commonly occurs due to motor vehicular collisions and results in tracheal injury as well as other thoracic and cervical injuries.[10] Blunt trauma primarily affects the thoracic trachea. In the cervical trachea, blunt trauma will typically cause damage to the cartilaginous portions. For blunt thoracic trauma, several theories attempt to explain the cause of tracheal injury. The first theory primarily occurs in crush injuries where increased force causes shortening of the anteroposterior axis and widening of the transverse axis with lungs remaining in contact with the chest wall and causing increased tension on the carina and resultant separation. Another theory suggests that increased pressure within the trachea causes rupture of the intercartilaginous membrane with the glottis closed. Some authors have also suggested that rapid deceleration like that seen in motor vehicle accidents causes shearing forces between the more affixed carina and the looser lung tissue.[9]

Iatrogenic injuries: Iatrogenic causes of tracheal trauma include percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy, endotracheal intubation, and rigid bronchoscopy. With endotracheal intubation, certain situations predispose the patient to complications, including emergency, the operator's skill, improper use of a stylet or high-pressure cuff, and manipulation of the tube with a blocked cuff. Risk factors for iatrogenic tracheal injury include individuals aged between 50 and 70 years, elevated BMI, female gender, and long-term use of corticosteroids. Most iatrogenic tracheal injuries tend to occur in the posterior membranous portion of the trachea.[4]

Inhalation and aspiration injuries: An endotracheal injury may result from inhalation or exposure to a noxious or hot gas, vapor, fumes, or foreign body aspiration. These types of tracheal injuries cause damage to the mucosal lining of the trachea, leading to inflammation, ulceration, and softening of the cartilaginous portions.[11]

Epidemiology

Most experts believe the incidence of tracheal trauma is underestimated as iatrogenic injuries are underreported, and there is a mortality rate of 82% in patients with traumatic injuries before arriving at the hospital.[5][2][12] An incidence of 1 in 125,000 cases of patients with laryngotracheal injury present to the emergency room, according to the US National Emergency Service Sample. Another review estimated an incidence of 1 in 30,000 patients presenting to the emergency department.[12] Overall, a tracheal injury is relatively uncommon in blunt trauma, with approximately 2.1% to 5.3% of patients with blunt chest trauma having this type of injury in some case studies. However, the majority of tracheal injuries are due to blunt trauma, including direct blows, compression or strangulation, and shearing injuries (eg, clothesline injuries) from sudden flexion, extension, or deceleration. Blunt trauma accounts for 60% of external laryngeal injuries. Approximately two-thirds of upper airway injuries involve the cervical trachea, while the remaining one-third are laryngeal injuries. While penetrating trauma to the trachea is also relatively uncommon, the trachea is the most common airway structure injured by stab wounds to the neck. When found, tracheal injury is more frequently seen in patients with concomitant cervical trauma and vascular or digestive tract injuries. When death results from this type of penetrating trauma, tracheal injury is most commonly associated with concomitant vascular injury rather than the airway injury itself. Failed or flawed intubation attempts are another potential cause of death in this population.

According to various case reports, tracheal injury due to endotracheal intubation is estimated at 0.005% to 0.37%.[5][2] Most injuries requiring tracheal reconstruction are iatrogenic and related to tracheostomies and endotracheal intubation. The most common among these are tube cuff injuries.[3] The incidence of inhalation injuries is estimated to be between 10% and 20% of all patients admitted with burn injuries.[13] Up to 25% of patients with acute laryngotracheal trauma requiring surgery have no physical evidence of the injury at initial presentation, and signs may be delayed for 24 to 48 hours. A high index of suspicion is necessary to avoid missing an occult injury, as delays in diagnosis and definitive treatment are associated with poorer outcomes. Mortality is relatively high in patients with acute trauma to the trachea, with a reported 15% to 40% range depending on mechanism and classification.[14]

Pathophysiology

Tracheal disruption may involve tracheal cartilages, most commonly from direct, blunt trauma. Tracheal tears or laryngotracheal separation may result from shearing forces in flexion and extension injuries. Chest crush injuries may cause sagittal tears of the membranous portions of the trachea and bronchi, often due to compression of the structures between the manubrium or sternum and vertebral column. Injury types include laryngotracheal contusions, lacerations, hematomas, avulsions, and fracture/dislocation of the tracheal cartilage. In rare cases, a complete transaction of the trachea may occur.[12]

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of tracheal trauma may vary depending on the mechanism of injury and involvement of adjacent structures. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and pneumothorax with or without respiratory failure are the most common clinical features observed in acute settings. Other symptoms include blood-tinged sputum, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, dysphagia, pneumoperitoneum, and chest pain.[2][5] Hoarseness is the presenting symptom in 85% of cases. Hemoptysis has been reported in 25% of cases secondary to concomitant mucosal trauma; severe hemoptysis may indicate vascular injury.[5] Presentations with delayed symptom onset are frequently noted with iatrogenic tracheal injuries (eg, extubation or endotracheal tube trauma) due to the endotracheal tube cuff temporarily sealing the injured area. Therefore, tracheal injuries should be suspected in patients with multiple traumatic injuries or mechanically ventilated, demonstrating persistent pneumothorax or air leakage or acute respiratory distress immediately following extubation.[2][5] Diagnosis of tracheal trauma based on clinical features alone is challenging due to differential diagnoses with similar presentations, such as rib fractures and traumatic chest injury, which can also have associated subcutaneous emphysema and pneumothorax.[5] In patients with subacute tracheal injuries (eg, tracheoesophageal fistulas and laryngotracheal stenosis), symptoms may include cough, aspiration, fever, dysphagia, hemoptysis, and chest pain.[15][16]

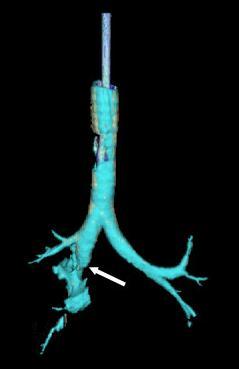

On physical exam, pertinent findings include stridor, cyanosis, dyspnea, voice changes or hoarseness, subcutaneous emphysema, and mediastinal crunch on auscultation. The laryngeal triad refers to the characteristic features of dyspnea, stridor, and hoarseness indicative of laryngotracheal trauma.[12] However, the absence of these findings does not exclude tracheal injury, as patients may be asymptomatic in the first 24 to 48 hours. Edema, deformed thyroid cartilage, crepitous, or decreased respiratory rate may also be observed on an exam.[12] Air bubbling from a penetrating neck wound indicates a tracheobronchial injury.[5] (see Image. Tracheal Injury)

Evaluation

When managing tracheal trauma, the initial approach in the emergency department, as always, is guided by the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, and Circulation). There should be a low threshold for definitive airway management when a tracheal injury is suspected, as there is a significant risk of rapid progression of edema, and the patient may be required to lay supine which may further compromise their airway. If signs of airway injury are present, ensuring and protecting airway patency are of paramount importance; evaluation of a tracheal injury may have to await appropriate airway management and treatment of coexisting traumatic injuries. Endotracheal intubation may be attempted, but a double set-up (with cricothyrotomy supplies at the bedside) is advisable. Because often there is a concern about induction and paralysis collapsing airway structures, awake intubation should be considered.[3] Other adjunctive measures include suctioning of secretions to prevent aspiration and enhance ventilation and oxygen supplementation as needed. Intravenous (IV) access should be secured, and fluid resuscitation should be started if indicated.

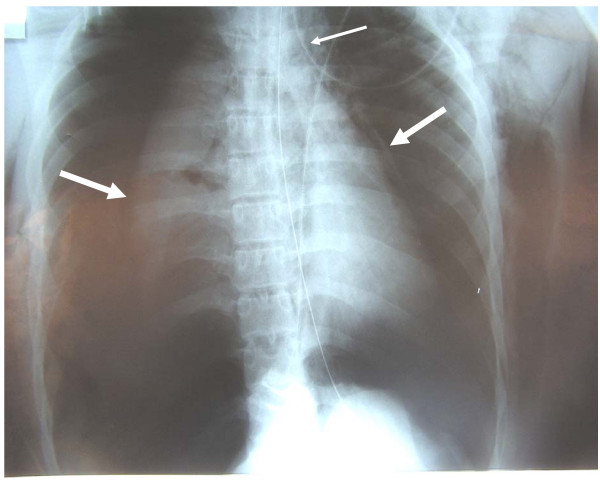

In acute trauma settings, after a patient's airway has been secured, the remaining trauma evaluation should be completed. Diagnostic modalities typically used to evaluate tracheal trauma include cervical or chest radiography, cervical or chest computed tomography (CT), or bronchoscopy. Chest x-ray is often the initial imaging study used to rapidly assess for pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, endotracheal or tracheostomy tube cuff overinflation, and tracheal deviation, findings that can suggest tracheal injury.[15] (see Image. Chest X-ray With Bilateral Pneumothoraces). If a tracheal injury is suspected in a stable patient, a CT of the neck and chest with IV contrast is the preferred modality to visualize pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, or pneumoperitoneum and concomitant injuries.[17][5] A patient with a potentially unstable unsecured airway should not be placed in a CT scanner, as a supine position will increase the risk of airway collapse. Up to 70% of patients with acute tracheobronchial injury will have a pneumothorax; 60% will have pneumomediastinum and cervical emphysema. While chest CT is superior to radiographs in diagnosis, it may still yield false negatives due to adjacent edema, hemorrhage, or secretions. CT has the added advantage of diagnosing injuries to adjacent structures, including sternal fractures and mediastinal hematomas, as well as vascular disruptions when IV contrast is used. Concomitant injuries to the great vessels, cricoid cartilage, laryngeal nerve, and esophagus which is involved in 25% of penetrating upper airway injuries, as well as cervical spine injuries that occur in 10% to 50% of patients with blunt airway injury, may be diagnosed by CT. secretions. A CT angiogram may also be performed to evaluate patients with possible vascular injury, particularly the carotid artery, the most commonly injured vessel with tracheobronchial trauma.[17][5]

However, bronchoscopy is considered the gold standard diagnostic study for tracheal trauma as this allows clinicians to characterize (eg, location and severity) tracheal injuries and determine the optimal management approach. Findings of tracheal injury with bronchoscopy include a deviated bronchial axis, mucosal bleeding or clots, laryngotracheal stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistulas, and tracheal tears. Direct visualization also confirms correct endotracheal tube positioning distal to the injury site.[2][18][5][15] Tracheal injuries are classified primarily using the Schaefer Classification System recommended by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. This grading system helps determine the severity of a tracheal injury and guides management decisions.[12][17]

Table 1. Schaefer Classification System [12]

| Grade | Injury |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

Another recently proposed classification system by Cardillo et al used the following grading system:

Table 2. Cardillo Tracheal Injury Classification

| Grade | Tracheal Injury |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3A |

|

| 3B |

|

Treatment / Management

Tracheal trauma management should be tailored to the patient's injuries, clinical presentation, and nature of the tracheal injury. According to the Schaefer Classification System, the grade of tracheal injury may guide management decisions.[12] When evaluating a patient with a tracheal injury, the primary initial treatment strategy is proper airway management and treatment of concomitant injuries. Early detection precipitated by a high degree of suspicion is essential to avoiding standard methods of securing an airway (ie, rapid sequence intubation) that may worsen a tracheal injury.[19] The ideal method for securing the airway in patients with tracheal injury is the awake placement of an endotracheal tube over a flexible bronchoscope and inflation of the cuff distal to the injury site. Patients with tracheal injury may benefit from awake intubation to limit apnea and loss of smooth muscle tone. Paralysis for intubation may lead to the collapse of a trachea that is already distorted and traumatized and being held open by the surrounding musculature. When the patient is rapidly desaturating, hemodynamically unstable, or awake, intubation is not tolerated; rigid bronchoscopy with inhalation induction may be the method of choice. This method is especially beneficial if clots, tissue, or strictures impair viewing the area of injury. However, rigid bronchoscopy is more difficult in patients with cervical instability who cannot extend their neck. Tracheostomy should be considered in patients with concomitant craniomaxillofacial injury or in whom previous attempts at endotracheal intubation were unsuccessful. Additionally, patients with penetrating cervical injuries could undergo the insertion of a tracheostomy tube directly through the site of injury, thereby preserving tissue for future repair.[20]

Conservative Management

In select patients with mild injuries, conservative management can be superior to surgical treatments.[20] Tracheal trauma best treated conservatively are usually the result of iatrogenic injury, have lacerations less than 2 cm long, involve a tracheal diameter of less than one-third, have no concomitant injury, and can be stabilized without the persistence of symptoms.[4] Small tracheal wounds typically heal spontaneously within 48 hours.[17] Fuhrman and Cardillo have established guidelines to aid in deciding if a tracheal injury is amenable to conservative treatment.[4][8][21] Conservative management typically consists of head elevation, steroids, antibiotics, humidification, voice rest, and antireflux medications.[17] Surgical adhesive glue for lacerations less than 5 mm has been utilized along with stenting for patients who are not good candidates for surgical repair.[22] An endoluminal repair may prove effective in patients who tolerate jet insufflation and have membranous posterior wall attachments.[4] Patients who undergo conservative management should be given humidified oxygen and observed in a critical care setting for deterioration. Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for 1 week.[2] Inhalation injuries should also be managed with early and aggressive intubation (with escalation to cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy as needed) due to the risk of rapid deterioration from laryngeal edema.

Surgical Management

Surgical repair of tracheal trauma may include repair of lacerations, reduction, and closure of fractured cartilages, and potentially end-to-end anastomosis if a complete transaction has occurred. Surgical exploration should occur within 24 hours of the injury to minimize subsequent scarring and airway stenosis. For similar reasons, if endolaryngeal stenting is used in the repair, it should be removed within 10 to 14 days. Stenting has become a mainstay of treatment for tracheal injuries. The primary types of stents are metallic and silicone, with metallic stents having varying degrees of coating. Both stent types are offered in straight, T, and Y shapes to accommodate the various injuries that can occur and can be placed with a rigid or flexible bronchoscope. For either stent, clinicians should ensure the airway is distal to the location requiring stenting and monitor for potential complications, including migration, fracture, infection, biofilm formation, and obstruction with either defective mucus passage or granulation tissue. Future advancements in stent technology may yield drug-eluting stents, 3-dimensional printed stents, and biodegradable products to reduce the complications seen with conventional stents.[23]

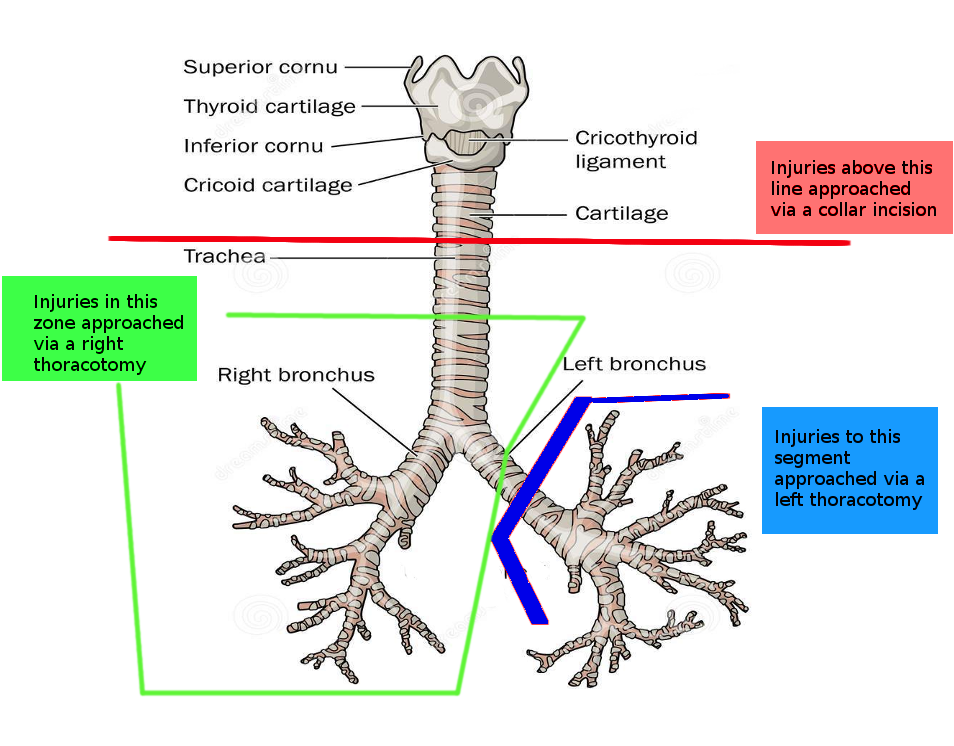

Even in patients with delayed diagnosis of tracheal injury, surgical management has proven beneficial in restoring lung function and reducing complications.[9] Location and concomitant injury guide the decision on approach. In general, cervical injuries can be approached through a collar incision.[4] Extension of the incision to the level of the second intercostal through the manubrium can provide access down to the innominate artery and vein.[4] The anterior neck muscles are dissected, revealing tracheal cartilages; a midline thyrotomy is then performed to expose the endolarynx, allowing for the repair of mucosal lacerations, closed with chromic sutures. If indicated, a laryngeal stent may be inserted and secured in place. When the laryngeal cartilages are fractured, stabilization and fixation may be aided by plating, which reduces movement of the fractured fragments and inflammation. Four-point fixation is utilized to hold the plate in place. If exposure to the hemithorax or mediastinum is required, a median partial sternotomy or clamshell incision could be utilized, but these do not provide better access to the trachea.[4] For tracheal injuries at the level of the carina or involvement of the bronchi, including the middle portion of the left main bronchus, a right anterolateral or posterolateral thoracotomy may be used.[4] Additionally, the distal portion of the left main bronchus can be approached through a left posterolateral thoracotomy if needed.[4] (see Image. Incisions for Tracheal Surgery)

Once access to the injured area has been obtained, the wound margins should be carefully debrided for primary closure using a 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable suture. Transverse wounds should be closed using a simple interrupted suture. Longitudinal repairs are most amenable to a continuous suture. In circumstances where extensive damage has occurred, such as complete transection of the trachea, following immediate airway rescue through a tracheostomy, the cricoid cartilage, if fractured, is repaired first. Circumferential resection with end-to-end anastomosis may be necessary, except for carina injuries; partial debridement with attempted primary repair is preferred.[24] Pericardial or mediastinal fat flap coverings may benefit injuries with impaired blood supply and the potential for wound dehiscence. In all closures, an absorbable suture should be used with the knots on the outside to avoid the formation of granulomas and strictures with lifelong irritation.[4] After repair, closed thoracic drainage and negative intrathoracic pressure may aid in the expansion of the lungs and occlusion of the repaired defect.[3] Consideration should also be given to head immobilization to reduce tension on repair for 1 to 2 weeks, continued antibiotic coverage, bronchoscopic assisted secretion removal, and incentive spirometry.[3] Steroids, proton pump inhibitors, and cough suppressants can also relieve strain on healing tracheal injuries.[8][25]

Table 3. Tracheal Trauma Recommendations and Schaefer Injury Grade [12]

| Grade | Evaluation Modality | Management |

| 1 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

With blunt and penetrating trauma being common causes of tracheal injury, adjacent structures are likely also to be involved. Concomitant injuries to the larynx, bronchi, lung parenchyma, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve, vagus nerve, carotid arteries, jugular veins, pulmonary trunk, aorta, and surrounding musculature require clinical consideration.[1] Other differential diagnoses include:

- Other causes of hypoxia and dyspnea (eg, pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion, or laceration)

- Airway obstruction with or without altered mental status due to a closed head or maxillofacial trauma

- Vascular injuries to great vessels of the thorax and neck with expanding hematoma

Prognosis

Prompt definitive care is associated with improved prognosis; delays may lead to scar tissue, strictures, infections, and other complications.[14] While mortality decreased from 36% before 1950 to 9% in 2001, prognosis greatly depends on early detection, concomitant injuries, and the cause of the injury.[20][9] Blunt tracheal injuries were associated with a better prognosis than crush injuries.[9] Of the fatal tracheal traumas found to have concomitant injuries, 40% to 100% of the tracheal injuries were determined to be the cause of death.[9] Early detection and appropriate treatment yield satisfactory outcomes in >90% of patients.[20]

Complications

While the immediate complication of tracheal injury is airway collapse, many additional complications need to be considered, even with appropriate management. Pulmonary infections, sepsis, and multi-organ system failure are major contributors to mortality.[20] Atelectasis and bronchiectasis can contribute to lasting decreased pulmonary function.[9] Other complications include:

- Aspiration

- Pneumothorax

- Airway obstruction due to hematoma or edema

- Chronic stenosis (long-term) due to scar tissue

- Associated conditions including difficulties with phonation, generally following blunt trauma, especially when definitive treatment is delayed by more than 24 hours

- Tracheoesophageal fistula

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

- Pulmonary and wound infections

- Subcutaneous emphysema or pneumomediastinum, which may cause progressive obstruction of the airway lumen and air embolus [4][26]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Following surgical repair of tracheal trauma, the following postoperative care should be considered:

- Following surgery in operative repair cases, the neck is fixed in flexion (ie, Pearson position) for 1 to 2 weeks to take pressure off the airway repair.

- Elevate the head of the bed to decrease edema.

- Use broad-spectrum antibiotics prophylactically.

- Ensure the endotracheal balloon does not overlie repair as it will inhibit healing.

Consultations

Consultations that are typically recommended include:

- Early otorhinolaryngology (ENT) involvement

- Interventional radiology (IR) and gastroenterology (GI) help investigate potential concomitant injuries to vascular or digestive structures, respectively.

Deterrence and Patient Education

With iatrogenic and traumatic causes of tracheal injury predominating, there are areas where both patients and clinicians can work to decrease the incidence of this condition. Utilization of low-pressure cuffs on endotracheal tubes, correct endotracheal tube size, avoidance of overinflation, and appropriate use of styles and bougies are some things clinicians can do to avoid tracheal injury. For difficult intubations and suspected tracheal injury, using flexible bronchoscopes allows visualization of potential injury and avoids creating false passages and worsening tracheal injury.[25]

Continued training and utilization of advanced trauma life support by healthcare clinicians will continue to reduce the mortality of tracheal injuries.[7] With motor vehicles playing a significant role in the incidence of blunt tracheal injury, continued advancements in safety features, including seatbelts and airbags that mitigate the frequency of injury, will help.[25][4] Using neck protection while participating in activities involving motorcycles or all-terrain vehicles could help avoid another area of traumatic injury.[25] Decreasing the incidence of suicide is an area that can help impact preventable tracheal injuries.[25]

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts that clinicians should bear in mind include:

- Tracheal trauma may result from penetrating, inhalation, or blunt mechanisms.

- A salient iatrogenic cause of tracheal trauma is endotracheal damage from an overinflated ETT cuff.

- The potential for tracheal trauma should be investigated early, as delays in diagnosis and treatment worsen the prognosis.

- Tracheal trauma may be associated with trauma to nearby structures, including bony disruptions of the cervical spine, vascular injury, or digestive tract involvement.

- Securing and protecting the airway early is of paramount importance

- Potential complications include pneumothorax, aspiration, and infections, as well as delayed airway stenosis or vocal cord dysfunction from scar tissue formation

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Tracheal trauma represents a high-risk, time-sensitive acute condition with the potential to affect the patient's ability to maintain an airway adversely. Tracheal trauma requires the collaborative efforts of multiple professionals. Care begins with emergency medical services to increase the number of tracheal injuries that survive en route to the emergency department.[7] A team-based approach, including emergency medicine, trauma, ENT specialists, and ancillary services, including nursing and respiratory therapy, is required for optimal initial stabilization. The extent of the injuries will require elucidation by direct visualization by an otolaryngologist or by review of imaging by a radiologist. For life-threatening injuries not amenable to conservative treatment, consultation with a surgical specialist is needed. Many of these patients will require close management within an intensive care unit where pulmonologists and infectious disease staff may work to avoid potential complications after injury repair; this can be significantly aided by trauma and surgically trained specialty nursing staff. Some patients require rehabilitation to regain pulmonary function and close follow-up to ensure proper healing. Definitive treatment, which often involves urgent surgical intervention, is beneficial; delays in definitive treatment have been associated with poorer outcomes.

With 70% to 80% of medical errors occurring due to poor communication and understanding, with a vast majority of those occurring in trauma situations, it is crucial to have good interprofessional collaboration. A Scopic review of interprofessional collaboration in trauma situations found successful teams to have fluid interactions, collaborative leaders, and post-trauma analysis. The interactions were further described as transforming from individuals in a team with independent actions to a team with interdependent actions. Successful leaders were found to be collaborative amongst not only their team but also between disciplines.[27] The primary motivator for improvement in these situations is improving patient outcomes; an interprofessional team approach, including clinicians, specialists, and trauma specialty-trained nursing staff, can improve outcomes for patients with a tracheal injury.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Tracheal Injury

Morgan Le Guen, Catherine Beigelman, Belaid Bouhemad, Yang Wenjïe, Frederic Marmion; modified by delldot on 12/17/09, Public Domain, via Wikipadia.org.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Chest X-ray With Bilateral Pneumothoraces

Morgan Le Guen, Catherine Beigelman, Belaid Bouhemad, Yang Wenjïe, Frederic Marmion, Public Domain, via Wickipedia.org.

References

Minnich DJ, Mathisen DJ. Anatomy of the trachea, carina, and bronchi. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2007 Nov:17(4):571-85. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18271170]

Grewal HS, Dangayach NS, Ahmad U, Ghosh S, Gildea T, Mehta AC. Treatment of Tracheobronchial Injuries: A Contemporary Review. Chest. 2019 Mar:155(3):595-604. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.07.018. Epub 2018 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 30059680]

Zhao Z, Zhang T, Yin X, Zhao J, Li X, Zhou Y. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of tracheal and bronchial injury. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017 Jan:9(1):E50-E56. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.01.19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28203437]

Welter S. Repair of tracheobronchial injuries. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2014 Feb:24(1):41-50. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.10.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24295658]

Boutros J, Marquette CH, Ichai C, Leroy S, Benzaquen J. Multidisciplinary management of tracheobronchial injury. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2022 Mar 31:31(163):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0126-2021. Epub 2022 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 35082126]

Peralta R, Hurford WE. Airway trauma. International anesthesiology clinics. 2000 Summer:38(3):111-27 [PubMed PMID: 10984849]

Cassada DC, Munyikwa MP, Moniz MP, Dieter RA Jr, Schuchmann GF, Enderson BL. Acute injuries of the trachea and major bronchi: importance of early diagnosis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000 May:69(5):1563-7 [PubMed PMID: 10881842]

Cardillo G, Carbone L, Carleo F, Batzella S, Jacono RD, Lucantoni G, Galluccio G. Tracheal lacerations after endotracheal intubation: a proposed morphological classification to guide non-surgical treatment. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2010 Mar:37(3):581-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.07.034. Epub 2009 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 19748275]

Kiser AC, O'Brien SM, Detterbeck FC. Blunt tracheobronchial injuries: treatment and outcomes. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2001 Jun:71(6):2059-65 [PubMed PMID: 11426809]

Juutilainen M, Vintturi J, Robinson S, Bäck L, Lehtonen H, Mäkitie AA. Laryngeal fractures: clinical findings and considerations on suboptimal outcome. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2008 Feb:128(2):213-8 [PubMed PMID: 17851956]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReid A, Ha JF. Inhalational injury and the larynx: A review. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Sep:45(6):1266-1274. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.10.025. Epub 2018 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 30529118]

Herrera MA, Tintinago LF, Victoria Morales W, Ordoñez CA, Parra MW, Betancourt-Cajiao M, Caicedo Y, Guzmán-Rodríguez M, Gallego LM, González Hadad A, Pino LF, Serna JJ, García A, Serna C, Hernández-Medina F. Damage control of laryngotracheal trauma: the golden day. Colombia medica (Cali, Colombia). 2020 Dec 30:51(4):e4124599. doi: 10.25100/cm.v51i4.4422.4599. Epub 2020 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 33795902]

Jayawardena A, Lowery AS, Wootten C, Dion GR, Summitt JB, McGrane S, Gelbard A. Early Surgical Management of Thermal Airway Injury: A Case Series. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2019 Feb 20:40(2):189-195. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/iry059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30445620]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAouad R, Moutran H, Rassi S. Laryngotracheal disruption after blunt neck trauma. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2007 Nov:25(9):1084.e1-2 [PubMed PMID: 18022512]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim HS, Khemasuwan D, Diaz-Mendoza J, Mehta AC. Management of tracheo-oesophageal fistula in adults. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2020 Dec 31:29(158):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0094-2020. Epub 2020 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 33153989]

Carpenter DJ, Hamdi OA, Finberg AM, Daniero JJ. Laryngotracheal stenosis: Mechanistic review. Head & neck. 2022 Aug:44(8):1948-1960. doi: 10.1002/hed.27079. Epub 2022 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 35488503]

Moonsamy P, Sachdeva UM, Morse CR. Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2018 Mar:7(2):210-216. doi: 10.21037/acs.2018.03.03. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29707498]

Miyawaki M, Ogawa K, Kamada K, Karashima T, Abe M, Takumi Y, Hashimoto T, Osoegawa A, Sugio K. Tracheal injury from dog bite in a child. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2023 Jan 16:18(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13019-023-02107-6. Epub 2023 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 36647124]

Shweikh AM, Nadkarni AB. Laryngotracheal separation with pneumopericardium after a blunt trauma to the neck. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2001 Sep:18(5):410-1 [PubMed PMID: 11559626]

Prokakis C, Koletsis EN, Dedeilias P, Fligou F, Filos K, Dougenis D. Airway trauma: a review on epidemiology, mechanisms of injury, diagnosis and treatment. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2014 Jun 30:9():117. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-9-117. Epub 2014 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 24980209]

Cheng J, Cooper M, Tracy E. Clinical considerations for blunt laryngotracheal trauma in children. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017 May:52(5):874-880. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.12.019. Epub 2016 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 28069269]

Madden BP. Evolutional trends in the management of tracheal and bronchial injuries. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017 Jan:9(1):E67-E70. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.01.43. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28203439]

Flannery A, Daneshvar C, Dutau H, Breen D. The Art of Rigid Bronchoscopy and Airway Stenting. Clinics in chest medicine. 2018 Mar:39(1):149-167. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2017.11.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29433711]

Altinok T, Can A. Management of tracheobronchial injuries. The Eurasian journal of medicine. 2014 Oct:46(3):209-15. doi: 10.5152/eajm.2014.42. Epub 2014 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 25610327]

Henry M, Hern HG. Traumatic Injuries of the Ear, Nose and Throat. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2019 Feb:37(1):131-136. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2018.09.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30454776]

Minard G, Kudsk KA, Croce MA, Butts JA, Cicala RS, Fabian TC. Laryngotracheal trauma. The American surgeon. 1992 Mar:58(3):181-7 [PubMed PMID: 1558336]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCourtenay M, Nancarrow S, Dawson D. Interprofessional teamwork in the trauma setting: a scoping review. Human resources for health. 2013 Nov 5:11():57. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-57. Epub 2013 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 24188523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence