Introduction

The lymphatic system is composed of lymphatic vessels and lymphoid organs such as the thymus, tonsils, lymph nodes, and spleen. These assist in acquired and innate immunity, in filtering and draining the interstitial fluid, and recycling cells at the end of their life cycle. The fluid that leaks from end-stage capillaries returns to the vascular system via the superficial and deep lymphatic vessels, which in turn drain into the right lymphatic duct and the thoracic duct. The right lymphatic duct travels on the medial border of the scalenus anterior muscle and drains the lymph from the right upper quadrant of the body. The thoracic duct starts at the cisterna chyli and has highly variable anatomy. The right lymphatic duct and the thoracic duct drain into the right and left subclavian arteries, respectively, at the jugulovenous angle.[1]

Lymph nodes are found at the convergence of major blood vessels, and an adult will have approximately 800 nodes commonly sited in the neck, axilla, thorax, abdomen, and groin. These filter incoming lymph and play a role in infection as well as in malignancy. This paper will discuss the structure and function of lymph nodes, as well as the anatomical divisions of these.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Lymph nodes are kidney-shaped and receive lymph via multiple afferent vessels, and filtered lymph then leaves via one or two efferent vessels. Nodes typically have an associated artery and vein, which terminates into a high endothelial venule (HEV). The HEV is the site of trans-endothelial migration of circulating lymphocytes due to T and B-cell endothelial surface receptors.[2]

Lymph nodes usually range in size from 1 to 2 cm and are enclosed in an adipose tissue capsule. Normal size depends upon location, as well as the axis which is being measured. The long axis should be 1 cm or less. They are considered pathological if they lose their oval shape, if there is a loss of the hilar fat, if there is an asymmetrical thickening of the cortex and if they are persistently enlarged.[3]

Lymph Node Structure[4]

Capsule

The capsule of the lymph node is dense connective tissue stroma and collagenous fibers. The capsule sends trabeculae inside the lymph node, which pass inward, radiating towards the center.

Subscapular Sinus

The subcapsular sinus is the space between the capsule and the cortex, which allows the transportation of the lymphatic fluid.; this is also called the lymph path, the lymph sinus, or the marginal sinus. The subcapsular sinus is present beneath the capsule and is traversed by both reticular fibers and cells. It receives the afferent vessels, continues with the trabecular sinuses, and joins the medullary sinus in the medulla of the lymph node.

Cortex

The cortex of the lymph node is the layer beneath the subcapsular sinus. The cortex is formed of the outer cortex and the inner part known as the paracortex. The outer cortex layer is also named the B-cell layer, is rich in CXCR5 chemokines, and consists mainly of B-cells arranged into follicles. The immature B-cells develop into a germinal center when challenged with an antigen. Following this, resting B-cell and dendritic cells surround the germinal center to form a mantle zone. The paracortex layer, also called the T-cell layer, consists of T-cells that interact with the dendritic cells and is rich in CCR7 chemokines.[5]

Medulla

The medulla is the innermost layer of the lymph node and contains large blood vessels, sinuses, and medullary cords. The medullary cords contain antibody-secreting plasma cells, B-cells, and macrophages. The medullary sinuses (or sinusoids) are vessel-like spaces that separate the medullary cords. The medullary sinuses receive lymph from the trabecular sinuses and cortical sinuses and contain reticular cells and histocytes. The medullary sinus drains the lymph into the efferent lymphatic vessels.

Function of Lymph Node[6]

The primary function of lymph nodes is filtering interstitial fluid collected from soft tissues and eventually returning it to the vascular system. Filtering this exudative fluid allows for exposure of T-cells and B-cells to a wide range of antigens. For antigen-specific B and T cells to activate, they must first suffer exposure to antigens with the aid of antigen-presenting cells, dendritic cells, and follicular dendritic cells. These form part of both the innate immune response and play a role in adaptive immunity.

Embryology

Lymph nodes begin their development in utero as mesenchymal condensation, which later bulges to form a lymph sac. At the 13th gestational week, the T-cell region begins to develop, and by the 17th gestation week, the interdigitating reticulum cells (a subtype of T-cells) are found in the paracortical lymph node region, surrounded by lymphoid cells. B-cell regions within lymph nodes start their development at the 14th gestation week at the marginal sinus with a population of dendritic reticulum cell precursors, lymphoblasts, immunoblasts, and plasmablasts. By the 20th gestation week, incipient primary follicles are observable in the outer cortex containing lymphocytes. During the 12th and 14th gestation weeks, lymph nodes undergo granulopoiesis and erythropoiesis to produce undifferentiated blast cells, monocytes, and macrophages temporarily.[7][8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Lymph Nodes of the Head and Neck

The lymph nodes in the head and neck are paired and broadly split into superficial and deep nodes.

Superficial

- Occipital nodes - At the lateral border of the trapezius muscles

- These drain the skin overlying the occiput.

- Mastoid (post-auricular) nodes - At the insertion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle on the mastoid process of the temporal bone

- These drain the posterior neck, the superior portion of the external ear, and the ear canal until the tympanic membrane.

- Pre-auricular nodes - Anterior to the tragus of the ear

- These drain the superficial face and temporal region.

- Superficial parotid nodes - Overlying the parotid gland.

- These drain the nose, the nasal cavity, part of the external ear canal, and the lateral orbit

- Submental nodes - Overlying the mylohyoid muscle.

- These drain the middle-lower lip, the floor of the mouth, and the tip of the tongue.

- Submandibular nodes - Found in the submandibular triangle, bounded by the inferior edge of the mandible and the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle, overlying the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles

- These drain the submental and facial nodes, the cheeks, the upper lip, and the marginal areas of the lower lip.

- Facial nodes - Comprised of maxillary, buccinator, and supramandibular lymph nodes

- These drain the mucus membranes of the inside of the cheek, the nasal mucosa, the eyelids, and the conjunctiva.

- Superficial cervical

- Anterior superficial cervical - Along the anterior jugular vein.

- These drain the superficial portions of the anterior neck.

- Posterior superficial cervical - Along the external jugular vein

- These also drain the superficial tissues of the neck.

- Anterior superficial cervical - Along the anterior jugular vein.

Deep

- Deep parotid - Found deep to the parotid gland.

- These drain the nasal cavity and the nasopharynx.

- Deep cervical - Found along the internal jugular vein. These are named prelaryngeal, pretracheal, retropharyngeal, infrahyoid, jugulodigastric, jugulo-omohyoid, and supraclavicular nodes, depending on their anatomical positional.

- These drain the superficial nodes and all of the head and neck.

In terms of anatomical dissection, these more easily split into levels of the neck.[9]

Level I

- Level Ia (submental nodes) - anteriorly, in the midline between the anterior bellies of the paired digastric muscles

- Level Ib (submandibular nodes) - in the submandibular triangle, as described above.

Level II

These nodes, also called the upper internal jugular nodes, are found in an anatomical area bounded by the base of the skull superiorly, the hyoid bone inferiorly, the submandibular gland anteriorly, the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle laterally, and the internal carotid artery medially. The spinal accessory nerve separates the level IIa and IIb nodes.

- Level IIa (jugulo-digastric nodes) - superficial or anterior to internal jugular vein

- Level IIb - deep or posterior to the internal jugular vein

Level III

These nodes are also names the middle internal jugular nodes and are bound superiorly by the hyoid bone, the cricoid cartilage inferiorly, the anterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, the posterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the common carotid artery medially.

Level IV

These nodes are also named the lower internal jugular nodes and include Virchow's node. The anatomical area in which they are found is bound superiorly by the cricoid cartilage, the clavicle inferiorly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, and the common carotid artery medially.

Level V

These are also named the posterior triangle nodes and are bounded by the convergence of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles superiorly, the clavicle inferiorly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly and medially, and the trapezius muscle posteriorly.

- Level Va - superior to the cricoid cartilage and include the spinal accessory nodes

- Level Vb - inferior to the cricoid cartilage and include the transverse cervical nodes and the supraclavicular nodes

Level VI

This level is also named the anterior compartment and contains the anterior jugular, pre-tracheal, para-tracheal, pre-cricoid, pre-laryngeal, and thyroid nodes. It is bound superiorly by the hyoid bone, inferiorly by the suprasternal notch, by the platysma muscle anteriorly, and the common carotid artery laterally.

Lymph Nodes of the Upper Limb

The deep and superficial lymphatics in the upper limb eventually drain into the axillary nodes. However, there are supratrochlear and cubital lymph nodes at the level of the elbow, brachial lymph nodes, and deltopectoral lymph nodes. The drainage of the upper limbs is particular due to the presence of sentry or sentinel lymph nodes. These are usually larger than the rest of the lymph nodes and are the first to filter the incoming lymph. However, it is not uncommon for multiple smaller sentry lymph nodes to also be present.[10][11]

Axillary Nodes

- Anterior nodes (pectoral) - They drain the breast and the anterior thoracic wall.

- Posterior nodes (subscapular) - They drain the posterior thoracic wall and the scapular area.

- Lateral nodes (humeral) - These are found posterior to the axillary vein and are the primary draining nodes for the upper limb.

- Central nodes - These are found close to the 2nd part of the axillary artery and receive lymph from the anterior, posterior, and lateral nodes.

- Apical nodes - These are located near the 1st part of the axillary artery and vein and filter the lymph received from the central axillary nodes and the cephalic vein.

The apical nodes further form the subclavian lymphatic trunk, which then drains into the right lymphatic duct.

Lymph Nodes of the Lower Limb

The superficial and deep lymphatic vessels of the lower limb drain into the inguinal lymph nodes in the femoral triangle. This anatomical region, also named Scarpa's triangle, is bounded by the inguinal ligament above, the medial border of the sartorius muscle laterally, and the medial border of the adductor longus muscle medially.[12][13]

Inguinal Nodes

The inguinal lymph nodes split at the level (where the great saphenous vein becomes the deep femoral vein) into sub-inguinal lymph nodes below and superficial inguinal nodes above.[3]

- Sub-inguinal nodes

- Superficial sub-inguinal nodes - These are found alongside the proximal saphenous vein and drain the superficial lymphatic vessels.

- Deep sub-inguinal nodes - These nodes are commonly found alongside the medial femoral vein and collect lymph from the deep lymphatic channels of the lower limb.

- Superficial inguinal nodes - These nodes are traditionally found immediately inferior to the inguinal ligament and drain the perineal area (penis, scrotum, perineum), the gluteal region, and part of the abdominal wall.

Iliac Nodes:[14]

- External iliac nodes

- Lateral external iliac lymph nodes - These are found lateral to the external iliac artery.

- Intermediate external iliac lymph nodes - These are found medial to the external iliac artery and anterior to the external iliac vein.

- Medial external iliac lymph nodes - These are found medial to the external iliac vein.

- Common iliac nodes - They commonly arise at the level of the aortic bifurcation (4th lumbar vertebra) and extend until the level of the common iliac bifurcation (2nd sacral vertebra)

- Lateral common iliac lymph nodes - These are found lateral to the common iliac artery.

- Intermediate common iliac lymph nodes - These appear alongside the posteromedial common iliac artery.

- Medial common iliac lymph nodes - These are alongside the medial common iliac artery.

Clinical Significance

The lymphatic system is involved in infective, inflammatory, and malignant diseases, and as such, enlargement of lymph nodes can be attributed to multiple causes. In the case of lymphadenopathy of unclear origin, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with or without fine-needle aspiration (FNA) can aid in diagnosis.[15] This diagnostic technique has been shown to have high accuracy with up to 85% sensitivity and 100% specificity and is key in detecting and staging malignancy.[16] With lymph nodes that are out of the scope of fine-needle sampling, elastography plays an increasingly important role, similar to obtaining a virtual biopsy.[17] Functional and anatomical data can be acquired using more traditional diagnostic methods such as positron emission tomography (PET) combined with computed tomography. However, this is commonly a whole-body imaging technique and therefore involves high doses of ionizing radiation. Despite the recent advancements in imaging modalities, the diagnosis still heavily relies on clinical correlation with symptoms.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lymphatic System. Illustrated anatomy includes the cervical lymph nodes, lymphatics of the mammary gland, cisterna chyli, lumbar lymph nodes, pelvic lymph nodes, lymphatics of the lower limb, thoracic duct, thymus, axillary lymph nodes, spleen, lymphatics of the upper limb, and inguinal lymph nodes.

Contributed by B Parker

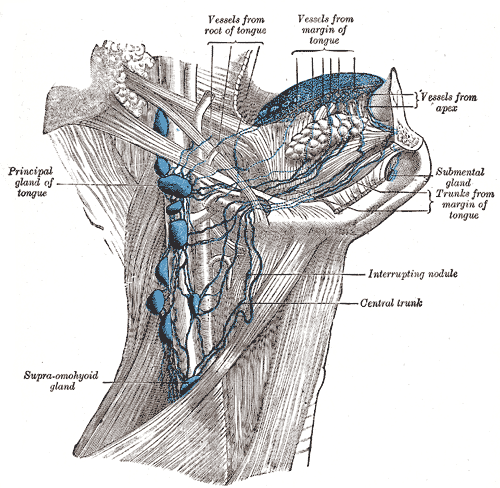

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

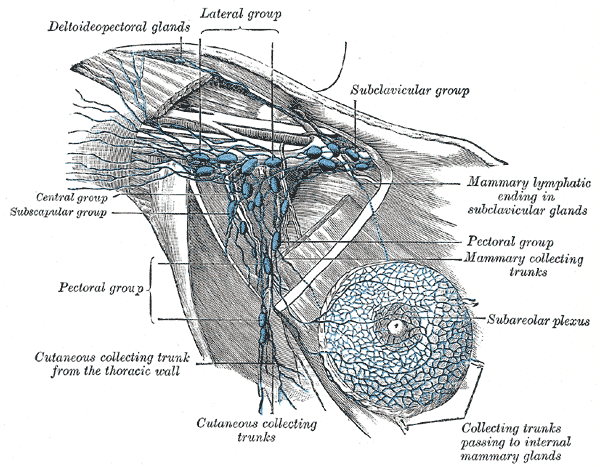

Anatomy of Axillary Lymph Nodes. Illustration of axillary lymph node anatomy, depicting the deltopectoral glands; lateral, subclavicular, central, subscapular, and pectoral groups; cutaneous and mammary collecting trunks; subareolar plexus; and mammary lymphatic ending in the subclavicular glands.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Johnson OW, Chick JF, Chauhan NR, Fairchild AH, Fan CM, Stecker MS, Killoran TP, Suzuki-Han A. The thoracic duct: clinical importance, anatomic variation, imaging, and embolization. European radiology. 2016 Aug:26(8):2482-93. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4112-6. Epub 2015 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 26628065]

Girard JP, Springer TA. High endothelial venules (HEVs): specialized endothelium for lymphocyte migration. Immunology today. 1995 Sep:16(9):449-57 [PubMed PMID: 7546210]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBontumasi N, Jacobson JA, Caoili E, Brandon C, Kim SM, Jamadar D. Inguinal lymph nodes: size, number, and other characteristics in asymptomatic patients by CT. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2014 Dec:36(10):1051-5. doi: 10.1007/s00276-014-1255-0. Epub 2014 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 24435023]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceElmore SA. Histopathology of the lymph nodes. Toxicologic pathology. 2006:34(5):425-54 [PubMed PMID: 17067938]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaldazzi V, Paci P, Bernaschi M, Castiglione F. Modeling lymphocyte homing and encounters in lymph nodes. BMC bioinformatics. 2009 Nov 25:10():387. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-387. Epub 2009 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 19939270]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiao S, von der Weid PY. Lymphatic system: an active pathway for immune protection. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2015 Feb:38():83-9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.11.012. Epub 2014 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 25534659]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarkgraf R, von Gaudecker B, Müller-Hermelink HK. The development of the human lymph node. Cell and tissue research. 1982:225(2):387-413 [PubMed PMID: 6980711]

Cupedo T. Human lymph node development: An inflammatory interaction. Immunology letters. 2011 Jul:138(1):4-6. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2011.02.008. Epub 2011 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 21333686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrégoire V, Ang K, Budach W, Grau C, Hamoir M, Langendijk JA, Lee A, Le QT, Maingon P, Nutting C, O'Sullivan B, Porceddu SV, Lengele B. Delineation of the neck node levels for head and neck tumors: a 2013 update. DAHANCA, EORTC, HKNPCSG, NCIC CTG, NCRI, RTOG, TROG consensus guidelines. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2014 Jan:110(1):172-81. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.10.010. Epub 2013 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 24183870]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSuami H, Taylor GI, Pan WR. The lymphatic territories of the upper limb: anatomical study and clinical implications. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2007 May:119(6):1813-1822. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000246516.64780.61. Epub [PubMed PMID: 17440362]

Cuadrado GA, de Andrade MFC, Akamatsu FE, Jacomo AL. Lymph drainage of the upper limb and mammary region to the axilla: anatomical study in stillborns. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2018 Jun:169(2):251-256. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4686-1. Epub 2018 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 29380209]

Pan WR, Wang DG, Levy SM, Chen Y. Superficial lymphatic drainage of the lower extremity: anatomical study and clinical implications. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 Sep:132(3):696-707. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829ad12e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23985641]

Pan WR, Levy SM, Wang DG. Divergent lymphatic drainage routes from the heel to the inguinal region: anatomic study and clinical implications. Lymphatic research and biology. 2014 Sep:12(3):169-74. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2014.0004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25229435]

Hsu MC, Itkin M. Lymphatic Anatomy. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2016 Dec:19(4):247-254. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2016.10.003. Epub 2016 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 27993319]

Hocke M, Ignee A, Dietrich C. Role of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in lymph nodes. Endoscopic ultrasound. 2017 Jan-Feb:6(1):4-11. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.190929. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28218194]

Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, Eltoum IA, Jhala D, Chhieng DC, Jhala N, Vickers SM, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of patients with suspected pancreatic cancer: diagnostic accuracy and acute and 30-day complications. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2003 Dec:98(12):2663-8 [PubMed PMID: 14687813]

Popescu A, Săftoiu A. Can elastography replace fine needle aspiration? Endoscopic ultrasound. 2014 Apr:3(2):109-17. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.123009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24955340]