Anatomy, Adenohypophysis (Pars Anterior, Anterior Pituitary)

Anatomy, Adenohypophysis (Pars Anterior, Anterior Pituitary)

Introduction

One of the unique glands in the human body is the pituitary gland. The gland is oval and weighs 500 mg. The dimension of the pituitary gland is about 12 mm transverse and 8 mm in anterior-posterior diameter. The pituitary is located in the hypophysial fossa, in a bony depression of the sphenoid bone called the sella turcica. The sella turcica surrounds the gland's inferior, anterior, and posterior aspects. Various structures surround the endocrine gland. The optic chiasma lies anteriorly, and the mammillary bodies lie posteriorly. Superior to the pituitary gland is the diaphragma sellae, the sphenoidal air sinuses are inferior, and the cavernous sinuses are lateral. A fold of dura matter covers the pituitary and has an opening to allow for the infundibulum to pass through, allowing a connection to the hypothalamus.[1][2][3]

The gland consists of 2 lobes:

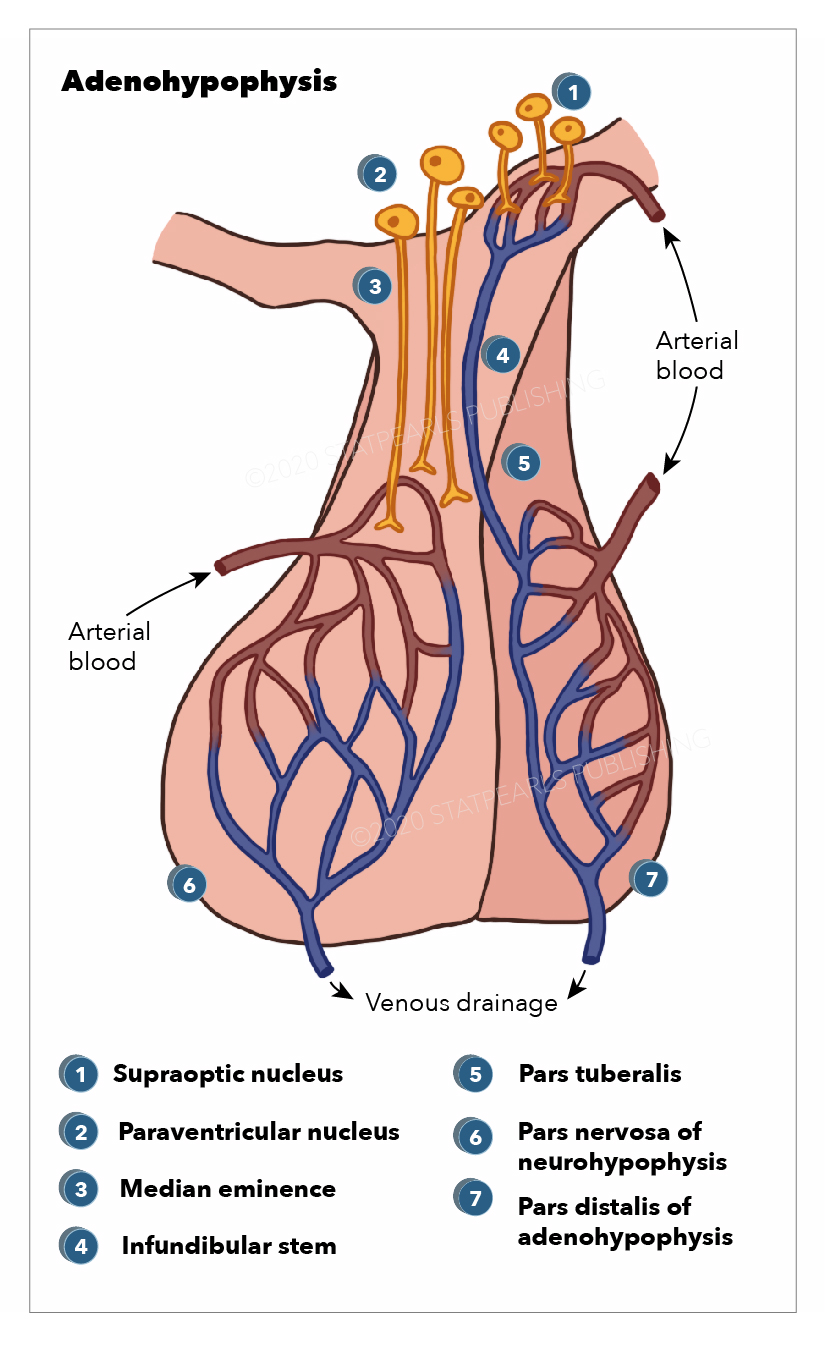

- Adenohypophysis (see Image. Anatomy, Adenohypophysis)

- Neurohypophysis

This topic focuses on the adenohypophysis. The anterior pituitary is composed of the following parts:

- Pars distalis: This is the portion where most hormone production occurs. It is the distal part of the pituitary and forms the majority of the adenohypophysis.

- Pars tuberalis: this tubular sheath extends from the pars distalis and winds around the pituitary stalk. Epithelial cells arranged in cords and hypophyseal portal vessels reside in this space.

- Pars intermedia: This is a tissue section between the posterior pituitary and pars distalis. This section of the adenohypophysis consists of large pale cells. These cells of the pars intermedia encompass follicles containing a colloidal matrix. The main hormone secreted by this portion of the adenohypophysis is MSH, otherwise known as the melanocyte-stimulating hormone.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The adenohypophysis produces and secretes a majority of the hormones of the pituitary gland. The following section enumerates the major hormones that are secreted.[4][5] These hormones are secreted in response to the prohormones secreted by the hypothalamus.

Well-demarcated acini characterize the adenohypophysis. These acini are composed of a mixture of different hormone-producing cells. The cells can be differentiated via hemotoxin and eosin (H and E) stains and the PAS-OG preparations. Based on these stains, 3 distinct cell types are seen.

- Acidophils: The cytoplasm of these cells stain red or orange. Acidophils usually contain polypeptide hormones. The cells that are acidophils are somatotrophs and lactotrophs. These cells have the largest size granules.

- Basophils: These cells have cytoplasm that stains a bluish or purple color. Basophils contain glycoprotein hormones. The basophils that secrete glycoprotein hormones are thyrotrophs, gonadotrophs, and corticotrophs.

- Chromophobes: These cells do not stain because they have minimal or no hormonal content. Many chromophobes may have been acidophils and basophils that have degranulated and released their hormones. Some are thought to be stem cells that have not differentiated into hormone-producing cells.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

ACTH hormone is secreted in response to corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus gland. The CRH would travel from the hypothalamus to its portal system. Upon reaching the adenohypophysis, it stimulates the cleavage of the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) into several molecules. The 3 major ones are ACTH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), and beta-endorphins. ACTH travels via the bloodstream to stimulate the adrenal cortex and help stimulate the production of cortisol. Cortisol also exerts negative feedback to inhibit the release of CRH and ACTH.[6]

Prolactin (PRL)

The hypothalamus primarily controls prolactin. Dopamine is the predominant hormone that inhibits the secretion of prolactin. When the hypothalamus receives afferent sensory nerve cell input from the nipple stimulation of lactating women, it causes the feedback loop of inhibition of prolactin to reverse. Due to the suckling, dopamine release is inhibited. This would allow an unopposed release of prolactin. Prolactin helps with the growth and development of the breasts and the maintenance of lactation in women.[7]

Luteinizing Hormone/Follicle Stimulating Hormone (LH/FSH)

These 2 hormones are produced by the gonadotrophin cells in the adenohypophysis. In women, LH acts on the ovaries to stimulate steroid hormone production. FSH stimulates the follicular development of the ovary in women, more specifically, the granulosa cells. In men, LH stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes to secrete testosterone. FSH stimulates the Sertoli cells to secrete androgen-binding proteins to initiate spermatogenesis. In both males and females, these hormones help stimulate the maturation of primordial germ cells. The control of LH and FSH is under the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) produced by the hypothalamus. There is a negative feedback loop for LH and FSH from steroid sex hormones. Inhibin allows for more specific feedback for FSH.[8][9]

Growth Hormone (GH)/Somatotropin

The growth hormone exerts its effects on many tissues. Growth hormone promotes linear growth via:

- The stimulation of protein synthesis

- Increasing the transport of amino acid through the cells [10]

GH stimulates the many tissues and the liver to produce somatomedins. Somatomedin helps stimulate cell division and cell proliferation. Somatomedins have the following effects:

- Enhance T-cell proliferation

- Increase in the absorption of calcium from the intestines and decrease the loss from urinary excretion

- Stimulates hepatic glycogenolysis to raise levels of glucose in the blood

- Increase in the growth of soft and skeletal tissues

- Increase uptake of non-esterified fatty acids by the muscle.

Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) is released by the hypothalamus, on which it reacts with the cells in the anterior pituitary. There is negative feedback on GH from the increase in the circulating concentrations of GH and IGF-1.

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH)

The purpose of TSH is to stimulate the thyroid gland, helping to produce and release T3 and T4. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is released via the hypothalamus to the adenohypophysis. The TRH stimulates thyrotrophic cells to secrete TSH.[11]

Embryology

The pituitary gland is a unique gland due to its dual origin. The organogenesis of the pituitary begins in the fourth week in the development of the fetus. It starts with the formation of a structure called a hypophyseal placode. This is formed when there is a thickening of the cells of the oral portion of the ectoderm. The hypophyseal placode brings forth Rathke’s pouch. The pouch extends upward in the direction of the neural ectoderm. It is simultaneously that there is a ventral portion of the diencephalon that gives a downward to expansion to form the neurohypophysis. Around 6 to 8 weeks, Rathke’s pouch would constrict at the base, allowing it to separate from the portion of oral epithelium. The cells in the pouch start to undergo proliferation. The anterior portion of the pouch wall undergoes rapid proliferation to give rise to the anterior part of the lobe of the pituitary (pars distalis). The posterior portion of the wall would proceed at a slower rate and give rise to the intermediate lobe (pars intermedia). An upward outward growth of the anterior wall would form the pars tuberalis.

The pituitary gland development can be a complex embryological process. Transcription factors control this process.

Pituitary Organogenesis Initiation Along with the Formation of Rathke’s Pouch

SIX

These are homeodomain proteins, a group of 6 transcriptional factor activators and inhibitors whose expression persists even in adulthood.

HESX-I

This homeobox gene expression begins in the cells that become Rathke’s pouch. It is important in the development of the optic nerves. Clinically, loss of function of this gene leads to solitary growth hormone deficiency, underdevelopment of the optic nerve, an absence of the septum pellucidum, and pituitary gland dysfunction, causing pituitary hormone deficiency.

Otx2

This transcription factor helps regulate Hesx1. Mutations in this factor also present as ocular disorders that might or might not give hypopituitarism.

Pitx forms 1, 2, and 3

Help decide cell lineage. Mutations are found in those with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. LH-beta and FSH-beta are not expressed.

Is11

Is11 is a transcription factor involved in specifying the lineage of the cells seen in thyrotrophs.

LHX3 and LHX4

LHX3 is seen in the early development of Rathke’s pouch. Without the LHX3, there would not be thickening of the Rathke’s pouch, sensorineural hearing loss, and a short, stiff neck. When there is a lack of LHX4, there is a marked reduction in the numbers of lactotrophs and somatotroph cells, pituitary hypoplasia, Chiari malformation, and small sella.

SOX2

The factor is expressed in the development of Rathke’s pouch. A mutation in this factor is seen in those with microphthalmia, growth hormone deficiency, and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Hypopituitarism would occur due to mutations that cause loss of function.

Beta-catenin

This factor would help activate Pitx2 expression. It is also required for cell lineage fate via Pit1 and the formation of the adenohypophysis.

Notch

It helps determine the fate of cell lineage, and lateral inhibition is mediated.

Migration of Rathke’s Pouch, Along with the Proliferation of the Cells

BMP2

Induces Is11 expression, but the prolonged expression of this factor would result in a hyperplastic pituitary.

BMP4

Required for the formation of the hypophyseal placode, the downregulation of this bone morphogenic protein would result in the arrested development of Rathke’s pouch.

Shh

This factor would be expressed in the ectoderm's oral portion and the diencephalon's ventral part.

Determination of Cellular Lineage and Differentiation of Cellular Components

Pit-I

This transcription factor is observed on the 14th day of fetal development and continues throughout life. Dimers are formed with other transcription factors, such as Zn-15, HESX-I, P-Lim, thyroid hormone, estrogen, and retinoic acid receptor. Loss of this transcription factor causes the loss of thyrotrophs, somatotrophs, and lactotrophs.

SF1

SF1 regulates the expression of GnRH, LH, FSH, and alphaGSU. This transcription factor is necessary for the differentiation of gonadotrophs. Mutations of gonadal dysgenesis in males and females would present with early ovarian failure.

GATA2

GATA2 specifies gonadotroph and thyrotroph lineages.

PROP-I

The product of this gene is required for its expression. Loss of this gene's expression leads to deficiencies in GH, prolactin, TSH, LH, and FSH.

TTF-I

Expression is normally seen in the brain and the posterior pituitary gland. In experimental mice, the disruption of this gene leads to pituitary gland aplasia. Out of all these transcription factors, the mutation of Pit-I and PROP-I leads to familial cases of multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply of the pituitary is unique because it is connected to the hypothalamus. This capillary system is known as the hypothalamohypophyseal portal system. The superior hypophyseal arteries form the primary capillary plexus. This plexus supplies blood to the median eminence. The blood from the median eminence would then drain via the hypophyseal portal veins in a secondary plexus. It is via this system that peptides released at the median eminence enter the primary plexus. From that point, the peptides would be transmitted to the adenohypophysis via the hypophyseal portal veins to the secondary plexus. The portal system has fenestrated capillaries that would allow for exchange between the hypothalamus and the pituitary. The cells of the adenohypophysis express G-protein coupled receptors that bind to the peptides, allowing the release of hormones from the anterior pituitary.

The majority of the blood supply of the adenohypophysis is derived from the paired superior hypophyseal arteries. These arteries arise from the medial aspect of the internal carotid artery just after leaving the cavernous sinus. The superior hypophyseal emerges 5 mm distal to the origin of the ophthalmic artery and then forms the primary capillary network found in the median eminence. This capillary plexus supplies blood to the pars distalis. The anterior and posterior hypophyseal portal veins drain the capillary plexus. Short veins from the pituitary gland drain into the neighboring dural venous sinuses.

Physiologic Variants

Variations of the pituitary gland sizes are seen regarding hormonal demands. Younger adults, especially those going through puberty, have larger glands. These glands entirely occupy the space of the pituitary fossa and have a large, convex upper border. Those individuals who are older tend to have an empty-looking pituitary fossa. The most dramatic change can be seen in pregnancy when it is dramatically enlarged and, in some cases, can be mistaken for an adenoma.

It has also been documented that sexual dimorphism exists. Through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), females ages 14 to 17 were documented to have a larger pituitary gland. Those females who were 19 years old, compared to those who were older (20 years and older), demonstrated this correlation between pituitary volume and age. Males did not show these phenomena.

Surgical Considerations

Surgery of the pituitary gland is considered when medical management has been deemed a failure, intolerable, or in cases of removal of pituitary tumors.

The best technique for pituitary surgery is transsphenoidal surgery. An endonasal incision creates a path to the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus. Once the sphenoid bone is broached (a fracture is created), the sellar floor can be penetrated with a durotomy to view the sellar region. The area is enhanced visually with an operative microscope. The advantages of going the transsphenoidal route allow there to be minimal surgical trauma, less blood loss, avoidance of generic complications of craniotomy, and direct visualization of the gland. Complications of transsphenoidal surgery include persistent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea, panhypopituitarism, transient DI, postoperative meningitis, cranial nerve injury, vascular damage, and stroke due to vasospasm or thromboembolism.[12]

However, recently, there has been an increase in the use of the transnasal transsphenoidal approach. This approach allows for a decreased hospital stay, an increase in patient comfort, and less nasal packing.

Clinical Significance

Rathke’s Pouch

Any remnants of Rathke’s pouch can produce mass-effect signs and symptoms. Rathke’s cleft cysts can accumulate fluid and start to expand, allowing compression of nearby structures. Vestigial remnants of the pouch can also form craniopharyngiomas. These benign tumors are slow-growing and are seen in young or very old people. These benign tumors are supersellers. They are mostly cystic but can be solid and encapsulated. Two forms of craniopharyngiomas are seen. The first is an adamantinomatous form, which contains calcifications and projections into the adjacent brain tissue. These projections can cause an intense inflammatory reaction. The second form, the papillary form, lacks the calcification and cysts and is much more approachable surgically.

Tumors

Pituitary gland tumors are common. Most arise from the adenohypophysis and are usually benign, nonsecretory adenomas. Pituitary adenomas can be classified as microadenomas (less than 1 cm) or macroadenomas (greater than 1 cm). The macroadenomas have a mass effect on the adjacent structures. If the pituitary gland itself is compressed, it can cause hypopituitarism. A macroadenoma can also compress the optic chiasm, resulting in bitemporal hemianopsia. Headaches, cranial nerve palsies, and hydrocephalus can also occur due to blockage of the outflow of the third ventricle.

The majority of secretory adenomas secrete a single hormone. Few (1% to 2%) secrete 2 or more hormones. Growth hormone and prolactin are examples of common dual hormone secretion. The most common secretory adenoma is prolactinomas. The bigger the secretory prolactin adenoma, the more hormone production there is. Prolactinomas can present with galactorrhea but may not always be present. The second most common secretory adenoma is growth hormone-secreting adenomas. This would be followed by ACTH-secreting adenomas, gonadotrophic adenomas (LH and FSH), and thyrotroph tumors.

Hyperprolactinemia

Hyperprolactinemia can be related to hypersecretion due to a prolactinoma, or it can be due to a “stalk effect.” The hypothalamus usually secretes dopamine, which is transported via the pituitary stalk to the adenohypophysis. In adenohypophysis, dopamine inhibits the lactotrophs from secreting prolactin. The transport of dopamine can be disrupted in 2 ways. A large macroadenoma with a suprasellar extension would cause this "stalk effect." There would be a disruption in the transport of dopamine. Head trauma would also cause a stalk effect. Lactotroph hyperplasia would develop without dopamine inhibition.

Lymphocytic Hypophysitis

Lymphocytic hypophysitis is an inflammatory disorder typically present during or after pregnancy. It is believed to be caused by an autoimmune process. Sarcoidosis (systemic inflammatory disease) can affect the pituitary as well, but it has to be differentiated from tuberculosis and syphilis.

Empty Sella Syndrome

The sella turcica may appear empty during radiological imaging due to a flattened or shrunken pituitary gland.

Primary Empty Sella syndrome: There is chronic intracranial hypertension along with a defect in the diaphragm sella. This would allow intradural contents to herniate into the Sella, allowing gland compression. Endocrine abnormalities would result in causing hypopituitarism and even visual symptoms of mass effect. This condition is most commonly seen in obese women with multiple pregnancies.

Secondary Empty Sella syndrome: A variety of problems can cause this condition. These can range from injury and trauma, treated pituitary tumors, infections, surgery in the pituitary region, or even Sheehan syndrome. This, too, can cause endocrine abnormalities.

Sheehan Syndrome

This occurs due to the infarction of the pituitary gland due to hypovolemia caused by obstetric hemorrhage. Usually, clinical manifestation occurs in the absence of milk production. The pituitary function can further decline over time.[13]

Pituitary Apoplexy

This is a life-threatening syndrome that calls for immediate neurosurgical treatment. There would be a sudden onset of visual dysfunction, severe headache, and pituitary insufficiency. This would call for immediate neurosurgical involvement.

Genetic Disorders

One common genetic disorder encountered in clinical practice is multiple endocrine neoplasia-1 (MEN-1).[14] Neoplastic growth is seen in the pancreas, parathyroid, and pituitary. Other genetic disorders in the PIT1 gene would cause deficiencies in GH, PRL, and TSH.

Developmental Abnormalities

Pituitary function failure can result from developmental abnormalities leading to a decrease or total failure of pituitary hormone failure.

Holoprosencephaly: During embryonic development, the fetal forebrain develops abnormally. This leads to an abnormal hypothalamus with associated facial dysmorphism. Facial abnormalities could include a cleft palate, absent nasal septum, and widely spaced eyes.

Septo-optic dysplasia: There is either absence of or hypoplasia of the optic chiasm, optic nerves, and the agenesis or hypoplasia of the septum pellucidum and corpus callosum.

Transcription factor mutations: Any mutations in the transcription factors (for example, PIT1) would lead to developmental abnormalities in the formation and differentiation of the pituitary gland.

Idiopathic Hypopituitarism

Other causes: Other causes can cause the pituitary gland to fail in the secretion of its hormones. Many conditions that can affect the pituitary include trauma, inflammation (bacterial, viral, or fungal), and radiation to the brain and hypothalamus. The effect of radiation depends on the age at which radiation and the dose of radiation.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Larkin S, Ansorge O. Development And Microscopic Anatomy Of The Pituitary Gland. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 28402619]

Nakayama T, Yoshimura T. Seasonal Rhythms: The Role of Thyrotropin and Thyroid Hormones. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2018 Jan:28(1):4-10. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0186. Epub 2017 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 28874095]

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Drummond JB, Ribeiro-Oliveira A Jr, Soares BS. Non-Functioning Pituitary Adenomas. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521182]

Jirikowski GF, Diversity of central oxytocinergic projections. Cell and tissue research. 2018 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 30498946]

Cao J, Lei T, Chen F, Zhang C, Ma C, Huang H. Primary hypothyroidism in a child leads to pituitary hyperplasia: A case report and literature review. Medicine. 2018 Oct:97(42):e12703. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012703. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30334955]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen MJ, Sharma S. Physiology, Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763207]

Al-Chalabi M, Bass AN, Alsalman I. Physiology, Prolactin. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939606]

Nedresky D, Singh G. Physiology, Luteinizing Hormone. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969514]

Orlowski M, Sarao MS. Physiology, Follicle Stimulating Hormone. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571063]

Rawindraraj AD, Basit H, Jialal I. Physiology, Anterior Pituitary. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763073]

Pirahanchi Y, Toro F, Jialal I. Physiology, Thyroid Stimulating Hormone. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763025]

Zubair A, Das JM. Transsphenoidal Hypophysectomy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310602]

Schury MP, Adigun R. Sheehan Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083621]

Singh G, Mulji NJ, Jialal I. Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725665]